Access to Healthcare for Minors: An Ethical Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)

1.2. Aims

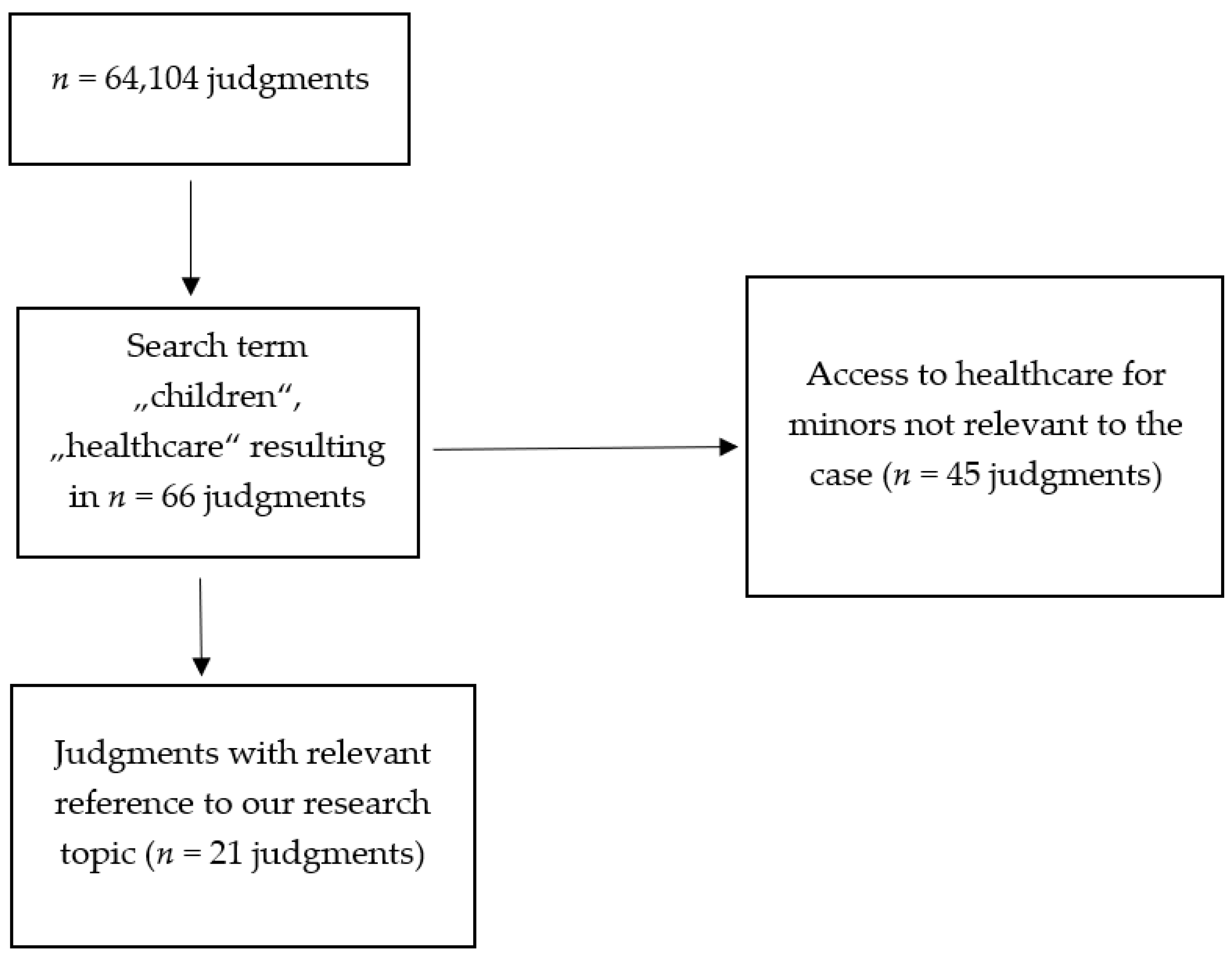

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.2. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Countries

3.2. Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights

3.3. Articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child

3.4. Categories

3.5. Governance Failure

3.6. Status of Refugee, Asylum Seeker or Migrant

3.7. Parental Home

3.8. Maternity and Birth

3.9. Other Cases

4. Discussion

4.1. Governance Failure

4.2. Status of Refugees, Asylum Seekers or Migrants

4.3. Parental Home

4.4. Maternity and Birth

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of the European Union. Presidency Conclusions of the Cologne European Council, 3–4 June, European Council Decision on the Drawing up of a Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. 1999. Available online: http://europa.eu.int/council/off/conclu/june99/june99_en.htm (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- World Health Organization. The Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1948. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, D.; Gibson, B.J.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What does ’access to health care’ mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gathron, E. Vulnerability in health care: A concept analysis. Creat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshua, P.; Zwi, K.; Moran, P.; White, L. Prioritizing vulnerable children: Why should we address inequity?: Prioritizing vulnerable children: Why should we address inequity? Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, K.M.; Wangmo, T.; Badarau, D.O.; Elger, B.S.; Niggli, F. Decision-making capacity of children and adolescents—Suggestions for advancing the concept’s implementation in pediatric healthcare. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisel, D.B. Vulnerable populations in healthcare. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 26, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostal, M.; Topinka, J.; Sram, R.J. Comparison of the health of Roma and non-Roma children living in the district of Teplice. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermette, D.; Shetgiri, R.; Al Zuheiri, H.; Flores, G. Healthcare access for Iraqi refugee children in Texas: Persistent barriers, potential solutions, and policy implications. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, S. Children of Jehovah’s Witnesses and adolescent Jehovah’s Witnesses: What are their rights? Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, M. Transgender children and the right to transition: Medical ethics when parents mean well but cause harm. Am. J. Bioeth. 2019, 19, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wärnestål, P.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J. Co-constructing child personas for health-promoting services with vulnerable children. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 3767–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, A. A right to access to emergency health care: The European Court of Human Rights pushes the envelope. Med. Law Rev. 2018, 26, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton-Glynn, C. Children and the European Court of Human Rights; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 85, 191–192, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study: Qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markkula, N.; Cabieses, B.; Lehti, V.; Uphoff, E.; Astorga, S.; Stutzin, F. Use of health services among international migrant children—A systematic review. Global Health 2018, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Werthern, M.; Grigorakis, G.; Vizard, E. The mental health and wellbeing of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URMs). Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 98, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto de Albuquerque, P. ECtHR Case of Lopes de Sousa Fernandes v. Portugal (56080/13), Partly Concurring, Partly Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pinto de Albuquerque. 2017. Available online: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22fulltext%22:[%2256080/13%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22GRANDCHAMBER%22,%22CHAMBER%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-179556%22]} (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Murray, L.K.; Nguyen, A.; Cohen, J.A. Child sexual abuse. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alanko, K.; Salo, B.; Mokros, A.; Santtila, P. Evidence for heritability of adult men’s sexual interest in youth under Age 16 from a population-based extended twin design. J. Sex Med. 2013, 10, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutajar, M.C.; Mullen, P.E.; Ogloff, J.R.P.; Thomas, S.D.; Wells, D.L.; Spataro, J. Psychopathology in a large cohort of sexually abused children followed up to 43 years. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Scott, J.; Alati, R.; O’Callaghan, M.; Najman, J.M.; Strathearn, L. Child maltreatment and adolescent mental health problems in a large birth cohort. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nanni, V.; Uher, R.; Danese, A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. AJP 2012, 169, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Classen, C.C.; Palesh, O.G.; Aggarwal, R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005, 6, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, S.; Briggs, E.C.; Woods, B.A. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Clin. N. Am. 2011, 20, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eurostat Press Release. Asylum Applicants Considered to Be Unaccompanied Minors, Almost 90,000 Unaccompanied Minors among Asylum Seekers Registered in the EU in 2015. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7244677/3-02052016-AP-EN.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- ISSOP Migration Working Group. ISSOP position statement on migrant child health. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonka, A.; Happle, C.; Grote, U.; Schleenvoigt, B.T.; Hampel, A.; Dopfer, C.; Hansen, G.; Schmidt, R.E.; Behrens, G.M.N. Measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella seroprevalence in refugees in Germany in 2015. Infection 2016, 44, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.; Vostanis, P.; Karim, K.; O’Reilly, M. Potential barriers in the therapeutic relationship in unaccompanied refugee minors in mental health. J. Ment. Health 2019, 28, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A.; Rosiek, S.; Slattery, B.; Chinapaw, M.; Van Hensbroek, M.B.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Holthe, J.K.-V. Pediatrician-experienced barriers in the medical care for refugee children in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 177, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. European Status Report on Preventing Child Maltreatment. 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/381140/wh12-ecm-rep-eng.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- World Health Organization. European Report on Preventing Child Maltreatment. 2013. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/217018/European-Report-on-Preventing-Child-Maltreatment.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Zeanah, C.H.; Humphreys, K.L. Child abuse and neglect. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.L. Child victimization in the context of family violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowe, E.R.; Townend, J.; Brocklehurst, P.; Knight, M.; Macfarlane, A.; McCourt, C.; Newburn, M.; Redshaw, M.; Sandall, J.; Silverton, L.; et al. Duration and urgency of transfer in births planned at home and in freestanding midwifery units in England: Secondary analysis of the Birthplace national prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilkington, H.; Blondel, B.; Drewniak, N.; Zeitlin, J. Where does distance matter? Distance to the closest maternity unit and risk of foetal and neonatal mortality in France. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Committee Opinion No 697 Summary: Planned home birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 129, 779–780. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FIGO Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health. Planned home birth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet 2013, 120, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton, J.T.; Navarro, A.M.; Young, S.H. Outcomes of planned home birth: An integrative review. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2007, 52, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuaimi, K.; Kassab, M.; Ali, R.; Mohammad, K.; Shattnawi, K. Pregnancy outcomes among Syrian refugee and Jordanian women: A comparative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Case | Violation of Articles of the Convention | Aspects of Judgments Related to Access to Healthcare for Minors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance failure | G.B. and Others v. Turkey (4633/15) | yes (Articles 3, 5, 13) | access to urgent medical care and healthy living conditions |

| P. and S. v. Poland (57375/08) | yes (Articles 3, 5, 8) | access to lawful abortion | |

| X and Others v. Bulgaria (22457/16) * | yes (Procedural limb of Article 3) | access to healthcare in orphanage | |

| Dubská and Krejzová v. The Czech Republic (28859/11 28473/12) * | no | access to healthcare during birthing at home | |

| Khan v. France (12267/16) | yes (Article 3) | access to healthcare and sanitation in refugee camp | |

| R.R. and Others v. Hungary (36037/17) | yes (Articles 3, 5) | access to vaccination for minor refugees | |

| Kurić and Others v. Slovenia (26828/06) | yes (Articles 8, 13) | access to healthcare after loss of citizenship | |

| Bistieva and Others v. Poland (75157/14) | yes (Article 8) | access to healthy living conditions in a detention center for migrants | |

| Blyudik v. Russia (46401/08) | yes (Articles 5, 8) | access to medical examination | |

| Refugee, asylum or migration | R.R. and Others v. Hungary (36037/17) | yes (Articles 3, 5) | access to vaccination of minor refugees |

| G.B. and Others v. Turkey (4633/15) | yes (Articles 3, 5, 13) | access to urgent medical care and healthy living conditions | |

| Khan v. France (12267/16) | yes (Article 3) | access to healthcare and sanitation in refugee camp | |

| M.A. v. Cyprus (41872/10) | yes (Articles 2, 3, 5, 13) | access to healthcare for minor asylum seekers | |

| Bistieva and Others v. Poland (75157/14) | yes (Article 8) | access to healthy living conditions in a detention center for migrants | |

| Parental home | Vavřička and Others v. The Czech Republic (47621/13 3867/14 73094/14 19298/15 19306/15 43883/15) | no | access to vaccination |

| Tlapak and Others v. Germany (11308/16 11344/16) | no | access to psychotherapy | |

| Wetjen and Others v. Germany (68125/14 72204/14) | no | access to healthcare | |

| V.D. and Others v. Russia (72931/10) | yes (Article 8) | healthy living conditions in families | |

| Ageyev v. Russia (7075/10) | yes (Article 8) | access to healthcare against the will of parents | |

| Maternity and birth | Konovalova v. Russia (37873/04) | yes (Article 8) | access to adequate healthcare and privacy during birthing |

| Dubská and Krejzová v. The Czech Republic (28859/11 28473/12) * | no | access to healthcare during birthing at home | |

| Kosaité-Čypiené and Others v. Lithuania (69489/12) | no | access to healthcare during birthing at home | |

| Others | V.C. v. Slovakia (18968/07) | yes (Articles 3, 8) | hostile perinatal treatment conditions towards a mother and her newborn child |

| N.D. and N.T. v. Spain (8675/15 8697/15) | no | medical assistance following illegal migration |

| Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights | Judgments Involving This Article | Judgments in Which at Least One Violation of This Article Was Found |

|---|---|---|

| Article 2 | n = 1 (4.76%) | n = 1 (4.76%) |

| Article 3 | n = 8 (38.09%) | n = 7 (33.32%) |

| Article 5 | n = 5 (23.8%) | n = 5 (23.8%) |

| Article 8 | n = 15 (71.42%) | n = 8 (38.09%) |

| Article 13 | n = 5 (23.8%) | n = 3 (14.28%) |

| Article 34 | n = 2 (9.52%) | n = 0 |

| Article 35 | n = 6 (28.57%) | n = 0 |

| Article 41 | n = 4 (19.04%) | n = 0 |

| Article 4 of Protocol No 4 | n = 2 (9.52%) | n = 0 |

| Articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child | Judgments Involving This Article |

|---|---|

| Article 2 | n = 1 (4.76%) |

| Article 3 | n = 6 (28.57%) |

| Article 9 | n = 2 (9.52%) |

| Article 19 | n = 1 (4.76%) |

| Article 20 | n = 5 (23.8%) |

| Article 22 | n = 1 (4.76%) |

| Article 24 | n = 2 (9.52%) |

| Article 37 | n = 3 (14.28%) |

| Article 44 | n = 1 (4.76%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tietze, F.-A.; Orzechowski, M.; Nowak, M.; Steger, F. Access to Healthcare for Minors: An Ethical Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101361

Tietze F-A, Orzechowski M, Nowak M, Steger F. Access to Healthcare for Minors: An Ethical Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. Healthcare. 2021; 9(10):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101361

Chicago/Turabian StyleTietze, Fabian-Alexander, Marcin Orzechowski, Marianne Nowak, and Florian Steger. 2021. "Access to Healthcare for Minors: An Ethical Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights" Healthcare 9, no. 10: 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101361

APA StyleTietze, F.-A., Orzechowski, M., Nowak, M., & Steger, F. (2021). Access to Healthcare for Minors: An Ethical Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. Healthcare, 9(10), 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101361