Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex

Abstract

1. Introduction

Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Engagement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

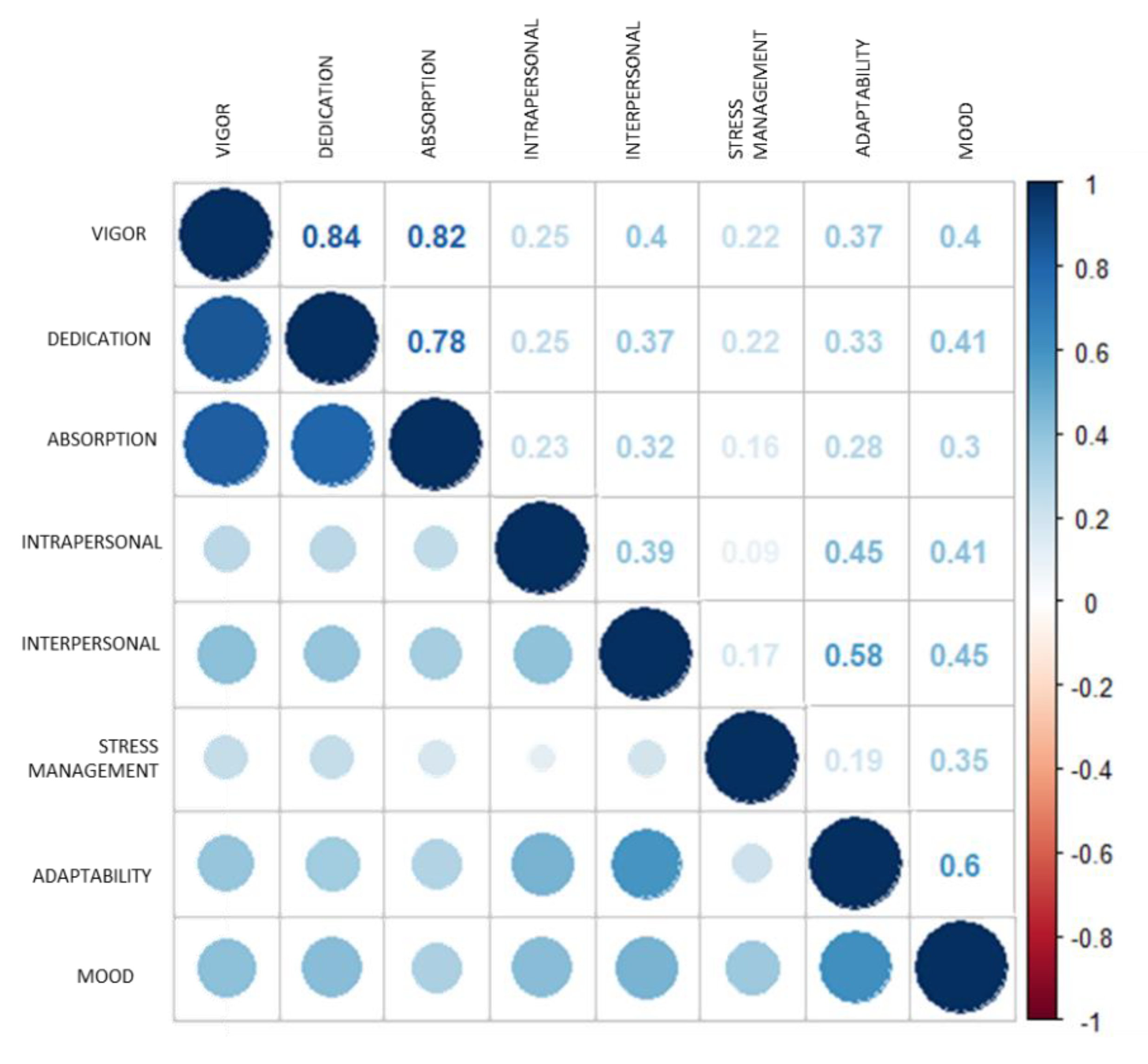

3. Results

3.1. Emotional Intelligence and Engagement by Sex

3.2. Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex

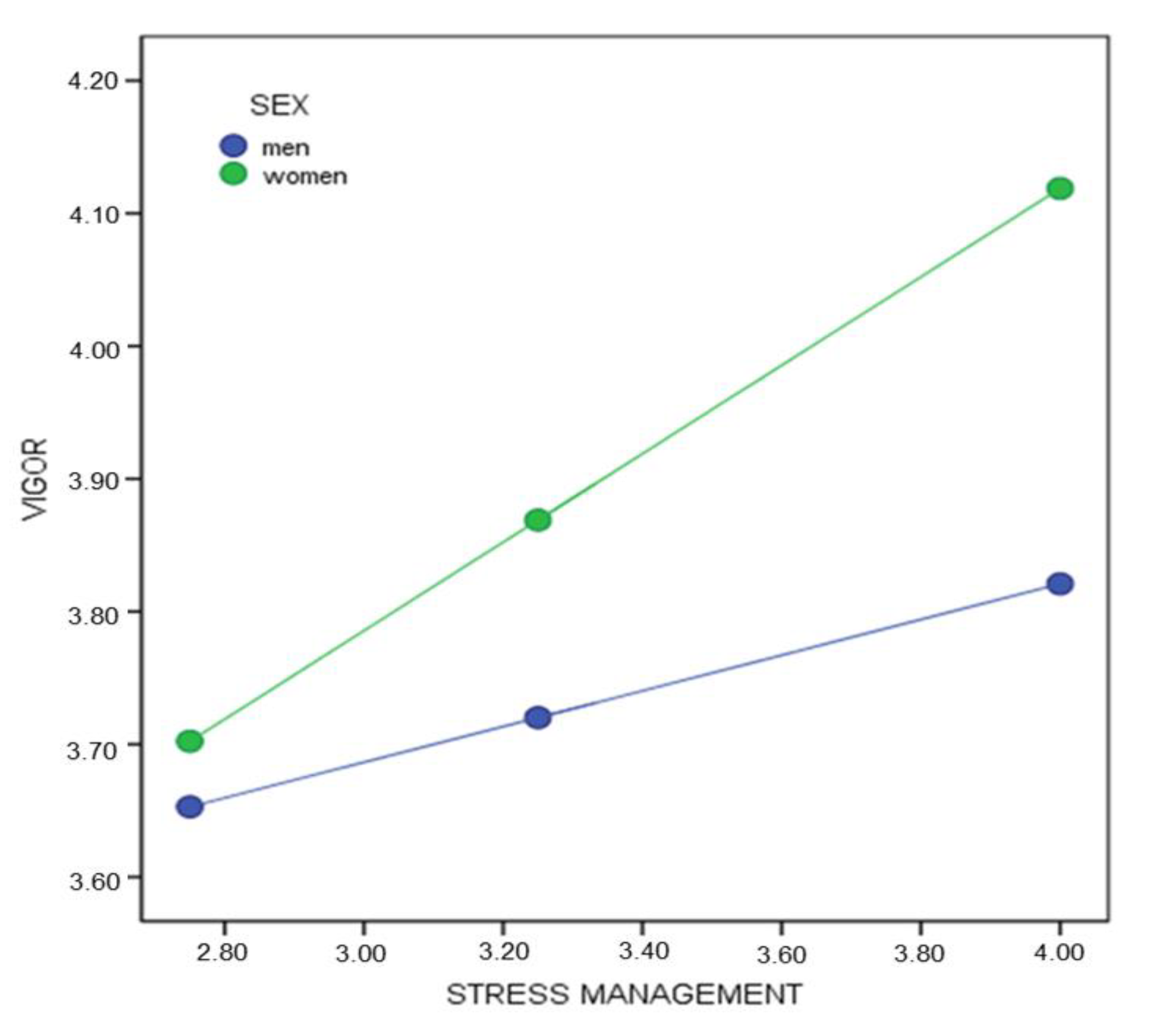

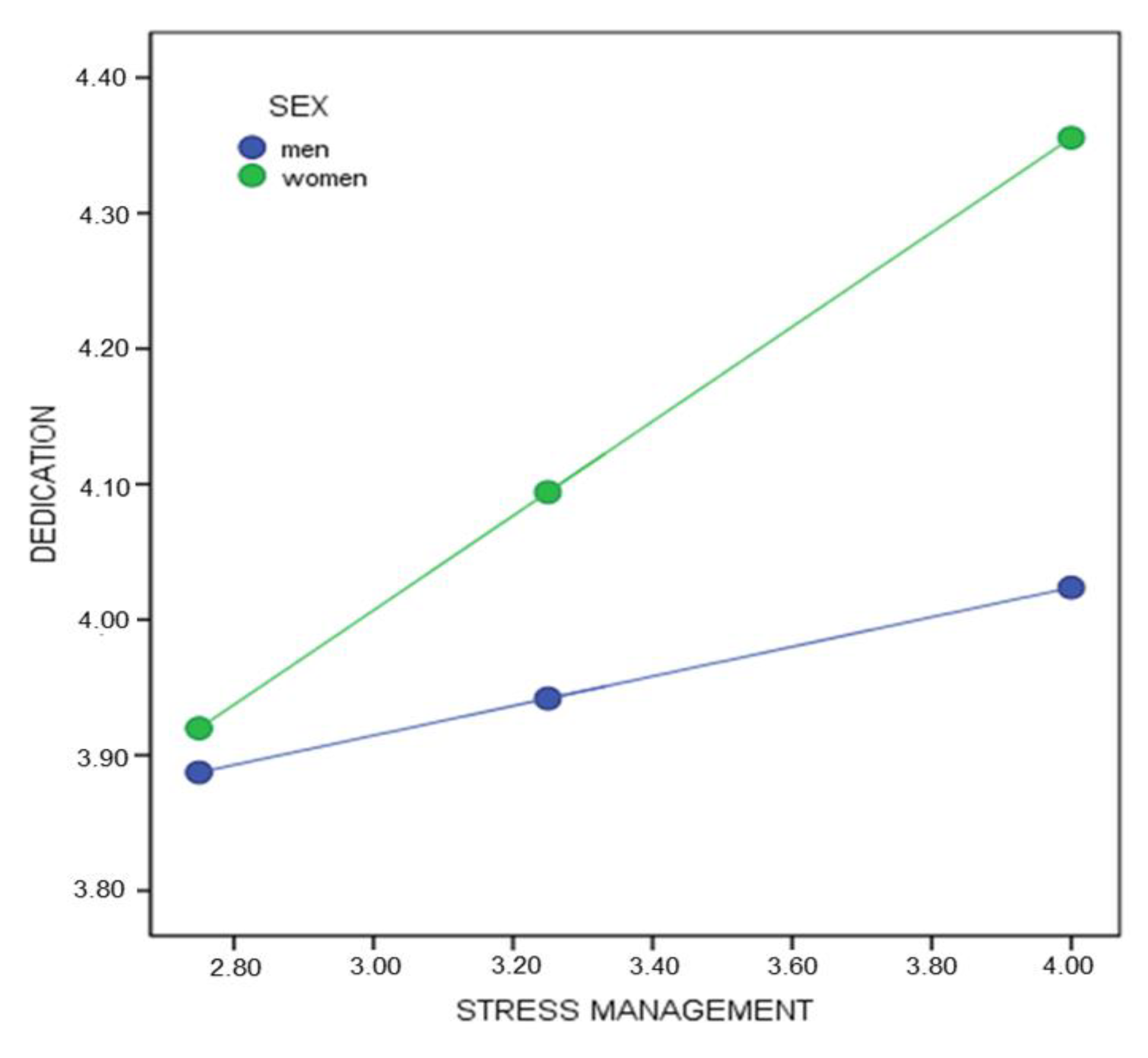

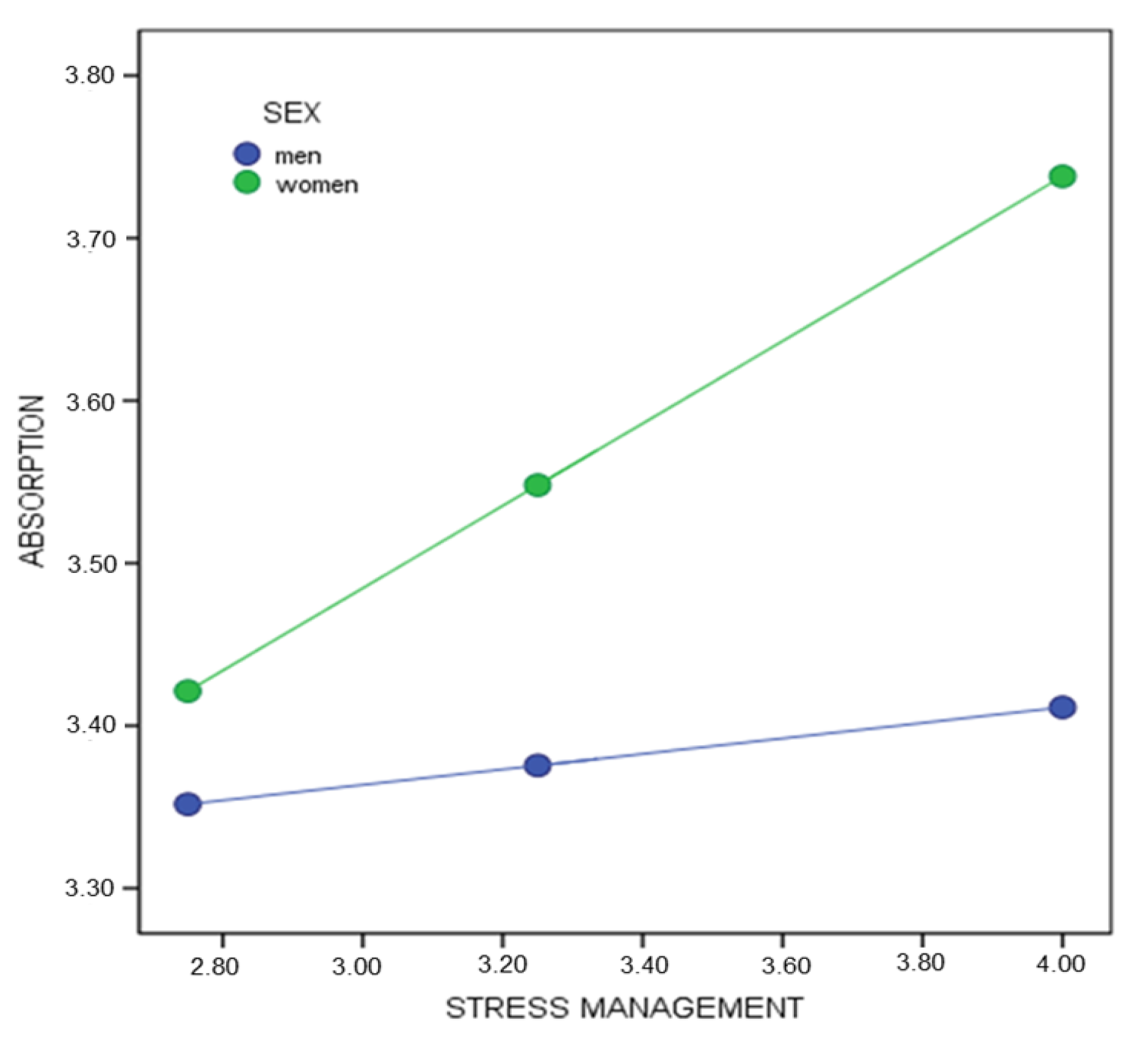

3.3. Moderation Analysis of Sex in the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Engagement

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-García, C.; Ruiz-Hernández, J.A.; Llor-Zaragoza, L.; Llor-Zaragoza, P.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.A. User Violence and Psychological Well-being in Primary Health-Care Professionals. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Legal Context 2018, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wersebe, H.; Lieb, R.; Meyer, A.H.; Hofer, P.; Gloster, A.T. The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2018, 18, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matula, P.; Uno, V. A causal relationship model work engagement affecting organizational citizenship behavior and job performance of professional nursing. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2016, 24, 1600–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Keyko, K.; Cummings, G.C.; Yonge, O.; Wong, C.A. Work engagement in professional nursing practice: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 61, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; GonzálezRomá, V.; Bakker, A. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S.L.; Leiter, M.P. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A. The intention to leave among nurses: the role of job satisfaction, self-efficacy and work engagement. La Med. Del Lav. 2017, 108, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J.; Simón, M.M. Analysis of burnout predictors in nursing: Risk and protective psychological factors. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Legal Context 2019, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso-Gómez, C.; Arias-Gundín, O. Resiliencia, optimismo y burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 11, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisa, N.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D.; Oldenburng, B. Effect of personal and work stress on burnout, job satisfaction and general health of hospital nurses in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 2017, 22, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sierra, R.; Fernández-Castro, J.; Martínez-Zaragoza, F. Engagement of nurses in their profession. Qualitative study on engagement. Enferm. Clin. 2017, 27, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A.; Cicotto, G. The role of job satisfaction, work engagement, self-efficacy and agentic capacities on nurses’ turnover intention and patient satisfaction. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahpouri, S.; Namdari, K.; Abedi, A. Mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between job resources and personal resources with turnover intention among female nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y. The mediating role of organizational commitment between calling and work engagement of nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 6, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisbona, A.; Palaci, F.; Salanova, M.; Frese, M. The effects of work engagement and self-efficacy on personal initiative and performance. Psicothema 2018, 30, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, Á.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J.; Simón, M.M.; Barragán, A.B. Burnout y engagement en estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2018, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francisco, C.; Arce, C.; Sánchez-Romero, E.I.; Vílchez, M.P. The mediating role of sport self-motivation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and athlete engagement. Psicothema 2018, 30, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, N.; Hiçdurmaz, D. Identifying emotional intelligence skills of Turkish clinical nurses according to sociodemographic and professional variables. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Extremera, N.; Rey, L. Self-Reported Emotional Intelligence, Burnout and Engagement among Staff in Services for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 95, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshaiqah, A.E.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Salem, O.A.; Zakari, N.M.A. The work engagement of nurses in multiple hospital sectors in Saudi Arabia: A comparative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Teo, S.; Shacklock, K.; Farr-Wharton, R. Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol-Granado, X.; Mendoza-Lira, M.; Covarrubias-Apablaza, C.G.; Molina-López, V.M. Positive emotions, autonomy support and academic performance of university students: The mediating role of academic engagement and self-efficacy. Revista de Psicodidáctica 2017, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasa, L.E.; Fargas, A.D. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Burnout in Healthcare Professionals. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, M.A.; Lucas-Molina, B.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Pérez-Albéniz, A.; Paino, M. Emotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence:Relationship with emotional well-being, affect, and academic performance. Anales de Psicología 2018, 34, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Han, J.W.; Kim, Y.H. Effect of Nurses’ Emotional Labor on Customer Orientation and Service Delivery: The Mediating Effects of Work Engagement and Burnout. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkavilli, M.; Kulkarni, S.; Doshi, D.; Reddy, S.; Reddy, P.; Reddy, S. Assessment of work engagement among dentists in Hyderabad. Work 2017, 58, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J.; Oropesa, N.F. The Role of emotional intelligence in engagement in nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Tejedor, E.; Hontangas, P.M.; Boada-Grau, J. Career adaptability and its relation to self-regulation, career construction, and academic engagement among Spanish university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 93, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; AsgharNejad, A.A.; Kharazi, M.J.; Khoei, N. Emotional intelligence of dental students and patient satisfaction. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, R.; Boustani, L.; Tsivrikos, D.; Chamorro-Premuzic, T. The engageable personality: Personality and trait EI as predictors of work engagement. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 73, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liut, C.; Guo, B.; Zhao, L.; Lou, F. The impact of emotional intelligence on work engagement of registered nurses: The mediating role of organisational justice. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A. UWES, Utrecht Work Engagement Scale; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mercader, I.; Molero, M.M. Brief emotional intelligence inventory for senior citizens (EQ-I-M20). Psicothema 2014, 26, 524–530. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R.; Parker, J.D.A. The Bar-on Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (EQ-i: YV); Technical Manual; MultiHealth Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| VIGOR | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 68.71 | 0.000 | 1.96 | ||

| 2 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.04 | 20.07 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 4.37 | 0.037 | |||

| Model 3 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.26 | 0.25 | 4.98 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mood | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 4.90 | 0.000 | 0.74 | 1.34 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 3.78 | 0.000 | 0.72 | 1.37 | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 2.09 | 0.037 | 0.80 | 1.23 | |||

| DEDICATION | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 72.96 | 0.000 | 2.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.77 | 0.05 | 24.60 | 0.000 | |||

| Model 2 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.22 | 0.27 | 4.49 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mood | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 5.52 | 0.000 | 0.78 | 1.27 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 4.96 | 0.000 | 0.78 | 1.27 | |||

| ABSORPTION | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 39.75 | 0.000 | 1.95 | ||

| 2 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 11.01 | 0.001 | |||

| 3 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 4.64 | 0.032 | |||

| Model 3 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.29 | 0.28 | 4.62 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Interpersonal | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 3.41 | 0.001 | 0.72 | 1.37 | |||

| Mood | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 2.79 | 0.005 | 0.74 | 1.34 | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 2.15 | 0.032 | 0.80 | 1.23 | |||

| VIGOR | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 333.82 | 0.000 | 1.96 | ||

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 128.96 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 28.76 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 12.84 | 0.000 | |||

| Model 4 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.10 | 0.12 | 8.67 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mood | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 6.77 | 0.000 | 0.56 | 1.76 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 8.78 | 0.000 | 0.64 | 1.55 | |||

| Stress Management | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 5.42 | 0.000 | 0.86 | 1.15 | |||

| Adaptability | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 3.58 | 0.000 | 0.51 | 1.93 | |||

| DEDICATION | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 352.21 | 0.000 | 1.92 | ||

| 2 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 86.32 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 30.45 | 0.000 | |||

| Model 3 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.45 | 0.12 | 11.26 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mood | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 10.44 | 0.000 | 0.70 | 1.41 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 9.34 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 1.26 | |||

| Stress Management | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 5.51 | 0.000 | 0.86 | 1.15 | |||

| ABSORPTION | Model | R | R2 | CorrectedR2 | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | ||||

| Std. Error of Estimation | Change in R2 | Change in F | Sig. of change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 187.95 | 0.000 | 1.95 | ||

| 2 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 68.24 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 12.18 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 8.71 | 0.003 | |||

| Model 4 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.36 | 0.13 | 9.82 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mood | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 7.76 | 0.000 | 0.74 | 1.33 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 5.44 | 0.000 | 0.63 | 1.56 | |||

| Stress Management | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 3.69 | 0.000 | 0.86 | 1.15 | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 2.95 | 0.003 | 0.76 | 1.30 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molero Jurado, M.d.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Barragán Martín, A.B.; Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Simón Márquez, M.d.M. Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex. Healthcare 2020, 8, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010042

Molero Jurado MdM, Pérez-Fuentes MdC, Barragán Martín AB, Gázquez Linares JJ, Oropesa Ruiz NF, Simón Márquez MdM. Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex. Healthcare. 2020; 8(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolero Jurado, María del Mar, María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, Ana Belén Barragán Martín, José Jesús Gázquez Linares, Nieves Fátima Oropesa Ruiz, and María del Mar Simón Márquez. 2020. "Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex" Healthcare 8, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010042

APA StyleMolero Jurado, M. d. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. d. C., Barragán Martín, A. B., Gázquez Linares, J. J., Oropesa Ruiz, N. F., & Simón Márquez, M. d. M. (2020). Emotional Intelligence Components as Predictors of Engagement in Nursing Professionals by Sex. Healthcare, 8(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010042