End-of-Life Care Challenges from Staff Viewpoints in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Information Sources

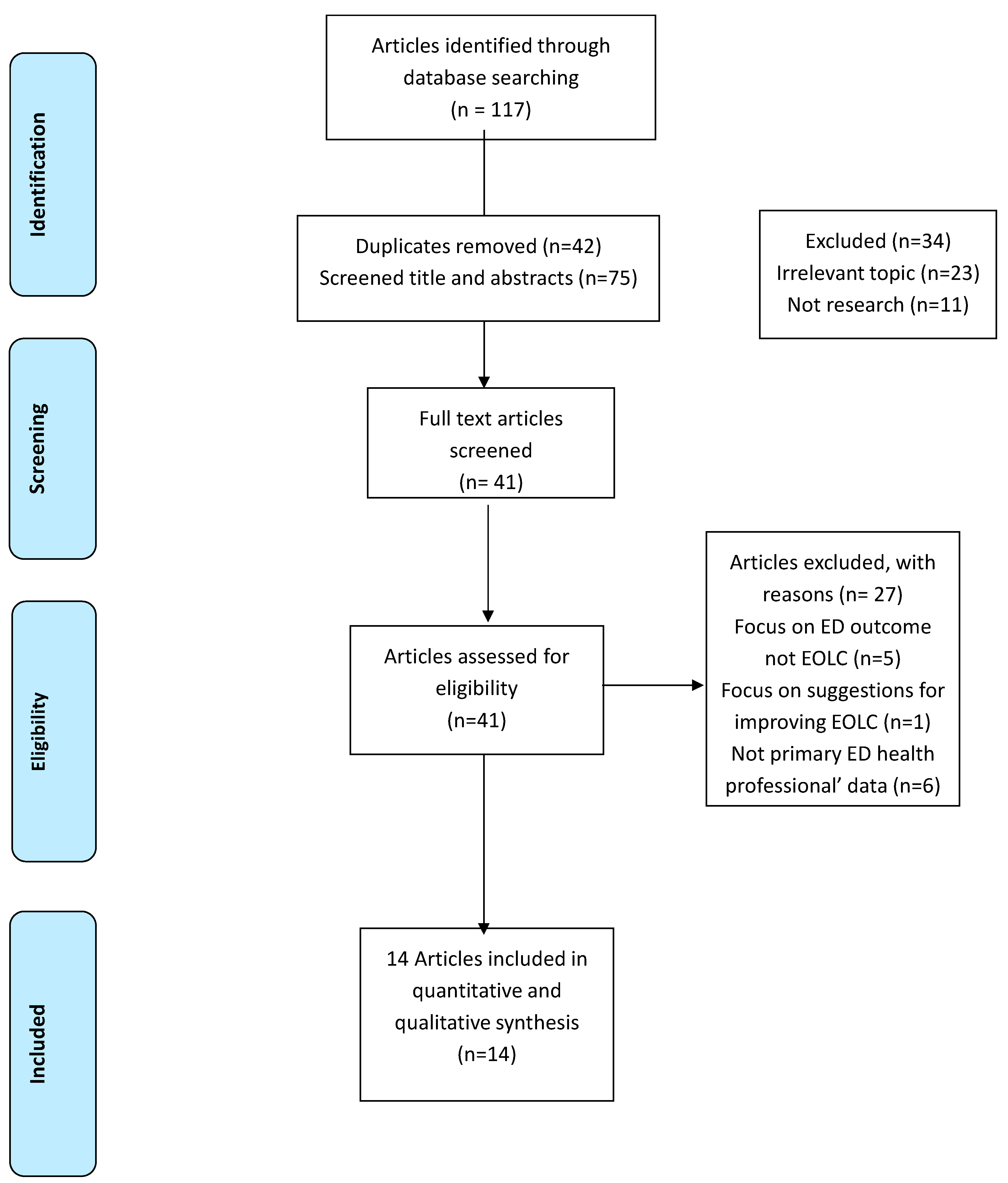

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Bias Rating and Quality Assessment

2.6. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Results

3.4. EOLC Education and Training

3.5. ED Design

3.6. Lack of Support for Families

3.7. Workload

3.8. ED Staff Communication and Decision-Making

3.9. EOLC Quality in EDs

3.10. Resource Availability (Time, Space, Appropriate Interdisciplinary Personnel)

3.11. Integrating PC in ED

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendation for Future Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forero, R.; McDonnell, G.; Gallego, B.; McCarthy, S.; Mohsin, M.; Shanley, C.; Formby, F.; Hillman, K. A Literature Review on Care at the End-of-Life in the Emergency Department. Emerg. Med. Int. 2012, 2012, 486516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanzaria, H.K.; Probst, M.A.; Hsia, R.Y. Emergency Department Death Rates Dropped by Nearly 50 Percent, 1997–2011. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Beckstrand, R.L.; Giles, V.C.; Luthy, K.E.; Callister, L.C.; Heaston, S. The last frontier: Rural emergency nurses’ perceptions of end-of-life care obstacles. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2012, 38, e15–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, B.J.; Burge, F.I.; McIntyre, P.; Field, S.; Maxwell, D. Palliative care patients in the emergency department. J. Palliat. Care 2008, 24, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.J.; Murphy, R.; Porock, D. Dying cases in emergency places: Caring for the dying in emergency departments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burge, F.; Lawson, B.; Johnston, G. Family physician continuity of care and emergency department use in end-of-life cancer care. Med. Care 2003, 41, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.K.; Schonberg, M.A.; Fisher, J.; Pallin, D.J.; Block, S.D.; Forrow, L.; McCarthy, E.P. Emergency department experiences of acutely symptomatic patients with terminal illness and their family caregivers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Norton, C.K.; Hobson, G.; Kulm, E. Palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department: Guidelines for nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2010, 37, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Nurses Association. Ethics in Practice, Respecting Choices in End-of-Life care: Challenges and Opportunities for RNs. Available online: https://canadian-nurse.com/~/media/canadian-nurse/files/pdf%20en/respecting-choices-in-end-of-life-care.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Care of Dying Adults in the Last Days of Life. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (accessed on 11 February 2018).

- Mitchell, G.K.; Senior, H.E.; Johnson, C.E.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; Williams, B.; Monterosso, L.; Rhee, J.J.; McVey, P.; Grant, M.P.; Aubin, M.; et al. Systematic review of general practice end-of-life symptom control. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.M.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Han, L.; Allore, H.G. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lash, R.S.; Bell, J.F.; Reed, S.C.; Poghosyan, H.; Rodgers, J.; Kim, K.K.; Bold, R.J.; Joseph, J.G. A Systematic Review of Emergency Department Use among Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau of Health Information. Spotlight on Measurement: Emergency Department Utilisation by People with Cancer; BHI, Ed.; Bureau of Health Information: Sydney (NSW), Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ddungu, H. Palliative care: What approaches are suitable in developing countries? Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 154, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snilstveit, B.; Oliver, S.; Vojtkova, M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.W.; Hung, M.S.; Pang, S.M. Emergency Nurses’ Perceptions of Providing End-of-Life Care in a Hong Kong Emergency Department: A Qualitative Study. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 42, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckstrand, R.L.; Rasmussen, R.J.; Luthy, K.E.; Heaston, S. Emergency nurses’ perception of department design as an obstacle to providing end-of-life care. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2012, 38, e27–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckstrand, R.L.; Rohwer, J.; Luthy, K.E.; Macintosh, J.L.; Rasmussen, R.J. Rural Emergency Nurses’ End-of-Life Care Obstacle Experiences: Stories from the Last Frontier. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 43, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckstrand, R.L.; Smith, M.D.; Heaston, S.; Bond, A.E. Emergency nurses’ perceptions of size, frequency, and magnitude of obstacles and supportive behaviors in end-of-life care. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2008, 34, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, K.A.; Fothergill-Bourbonnais, F.; Brajtman, S.; Phillips, S.; Wilson, K.G. When Someone Dies in the Emergency Department: Perspectives of Emergency Nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 42, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassier, T.; Valour, E.; Colin, C.; Danet, F. Who Am I to Decide Whether This Person Is to Die Today? Physicians’ Life-or-Death Decisions for Elderly Critically Ill Patients at the Emergency Department-ICU Interface: A Qualitative Study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016, 68, 28–39.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, F.M.; Rogers, I.R.; Monterosso, L.; Ross-Adjie, G.; Rogers, J.R. Understanding emergency department staff needs and perceptions in the provision of palliative care. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2014, 26, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Molina, J.; del Mar Díaz-Cortés, M.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; García-Caro, M.P.; Fernández-Sola, C. Loss of Dignity in End-of-Life Care in the Emergency Department: A Phenomenological Study with Health Professionals. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 42, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, S.C.; Mohanty, S.; Grudzen, C.R.; Shoenberger, J.; Asch, S.; Kubricek, K.; Lorenz, K.A. Emergency medicine physicians’ perspectives of providing palliative care in an emergency department. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.; Murphy, R.; Porock, D. Trajectories of end-of-life care in the emergency department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2011, 57, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L.A.; Delao, A.M.; Perhats, C.; Clark, P.R.; Moon, M.D.; Baker, K.M.; Carman, M.J.; Zavotsky, K.E.; Lenehan, G. Exploring the Management of Death: Emergency Nurses’ Perceptions of Challenges and Facilitators in the Provision of End-of-Life Care in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2015, 41, e23–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongsuwan, W.; Matchim, Y.; Nilmanat, K.; Locsin, R.C.; Tanioka, T.; Yasuhara, Y. Lived experience of caring for dying patients in emergency room. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Greenslade, J.; Isoardi, J.; Davey, M.; Gillett, M.; Tucker, A.; Klim, S.; Kelly, A.M.; Abdelmahmoud, I. End-of-life issues: Withdrawal and withholding of life-sustaining healthcare in the emergency department: A comparison between emergency physicians and emergency registrars: A sub-study. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2016, 28, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlet, J.; Thijs, L.G.; Antonelli, M.; Cassell, J.; Cox, P.; Hill, N.; Hinds, C.; Pimentel, J.M.; Reinhart, K.; Thompson, B.T. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, T.J.; Lane, H.; Jelinek, G.A.; Marck, C.H.; Weil, J.; Boughey, M.; Philip, J. Managing the advanced cancer patient in the Australian emergency department environment: Findings from a national survey of emergency department clinicians. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, M.M.; Al-Jawarneh, Y.; Hammami, M.B.; Al Qadire, M. Information disclosure in clinical informed consent: “reasonable” patient’s perception of norm in high-context communication culture. BMC Med. Ethics 2014, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Alexander, S.C.; Garrigues, S.K.; Arnold, R.M.; Barnato, A.E. Communication practices in physician decision-making for an unstable critically ill patient with end-stage cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galushko, M.; Romotzky, V.; Voltz, R. Challenges in end-of-life communication. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 6, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northwestern University. Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care. Available online: http://bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/curricula/emergency.html (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Decker, K.; Lee, S.; Morphet, J. The experiences of emergency nurses in providing end-of-life care to patients in the emergency department. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2015, 18, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, M.M.; Al Gaai, E.; Hammami, S.; Attala, S. Exploring end of life priorities in Saudi males: Usefulness of Q-methodology. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life; WHO: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Source, Country and Quality | Aim | Design and Method | Setting | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author: Beckstrand et al., 2008 Country: USA Weak quality * [21] | To determine a magnitude score for both obstacles and supportive behaviours surrounding EOL care in emergency departments. | Cross-sectional using a validated questionnaire | Emergency department, Multisite | 272 emergency nurses. |

| Author: Beckstrand et al., 2012 Country: USA Weak quality * [19] | To determine the impact of ED design on EOL care as perceived by emergency nurses and to determine how much input emergency nurses have on the design of their emergency department. | Cross-sectional using a developed questionnaire | Emergency department, Multisite | 198 emergency nurses. |

| Author: Beckstrand et al. 2012. Country: USA Weak quality * [3] | To discover the size, frequency, and magnitude of obstacles in providing EOL care in rural emergency departments as perceived by rural emergency nurses. | Cross-sectional survey research design | Emergency department in rural area. Multisite | 236 emergency nurses |

| Author: Wolf et al., 2015. Country: USA Weak quality * [28] | To explore emergency nurses’ perceptions of challenges and facilitators in the care of patients at the EOL. | A mixed-methods design | Emergency department, Multisite | Survey data (N = 1879) Focus group data (N = 17) |

| Author: Beckstrand et al., 2017 Country: USA Weak quality * [20] | To explore the first-person experiences or stories of rural emergency nurses who have cared for dying patients and the obstacles these nurses encountered while attempting to provide EOL care. | Cross-sectional survey | Emergency department, Multisite | 246 Emergency nurses. |

| Author: Hogan et al., 2016 Country: Canada High quality * [22] | To describe the experience of emergency nurses who provide care for adult patients who die in the emergency department to better understand the factors that facilitate care or challenge nurses as they care for these patients and their grieving families. | Qualitative design (Semi-structured interviews) | Two EDs of a multisite university teaching hospital | 11 Emergency nurses. |

| Author: Granero-Molina et al., 2016 Country: Spain High quality * [25] | To explore and describe the experiences of physicians and nurses with regard to loss of dignity in relation to end-of-life care in the emergency department. | Qualitative design (Phenomenological study) | Two EDs of public hospitals, multisite | 26 emergency staff (10 physicians and 16 nurses) |

| Author: Tse, Hung and Pang, 2016 Country: Hong Kong Weak quality * [18] | To understand emergency nurses’ perceptions regarding the provision of EOLC in the ED. | Qualitative study. (Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews) | Emergency Department | 16 Emergency Nurses. |

| Author: Bailey, Murphy and Porock, 2011 Country: UK High quality * [27] | To explore end-of-life care in the ED and provide an understanding of how care is delivered to the dying, deceased and bereaved in the emergency setting. | Qualitative study (Observation and interviews) | ED in an urban academic teaching hospital | Emergency nurses (11), physicians (2), and technicians (2) (7) Patients who had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. (7) relatives, who had accompanied the patients during the emergency admission |

| Author: Fassier, Valour, Colin and Danet, 2016 Country: France High quality * [23] | To explored physicians’ perceptions of and attitudes toward triage and end-of-life decisions for elderly critically ill patients at the emergency department –ICU interface | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | EDs in Hospitals, multisite | 15 Emergency physicians |

| Author: Stone et al., 2011 Country: USA High quality * [26] | To describe emergency physicians’ perspectives on the challenges and benefits to providing palliative care in an academic, urban, public hospital in Los Angeles | Qualitative study (semi- structured interviews) | ED in a large, public, urban academic medical centre | 38 Emergency Medicine Physicians |

| Author: Kongsuwan et al., 2016 Country: Thailand High quality * [29] | To describe the meaning of nurses’ lived experience of caring for critical and dying patients in the emergency rooms. | Qualitative Study using phenomenological approach (in-depth interviews) | EDs in hospitals, multisite | 12 emergency nurses. |

| Author: Richardson et al., 2016 Country: Australia High quality * [30] | To investigate and describe any differences in the importance of the considerations and discussions that took place when EP and ER made a decision to withdraw and/or withhold life-sustaining healthcare in the ED. | Sub-study of a prospective cross-sectional questionnaire-based case series | In six metropolitan EDs, multisite | 185 Emergency consultants, 135 emergency training registrars and 320 EOL patients |

| Author: Shearer, Rogers, Monterosso, Ross-Adjie and Rogers, 2014 Country: Australia Weak quality * [24] | To investigate Australian ED staff perspectives and needs regarding palliative care provision and to assess staff views about death and dying, and their awareness of common causes of death in Australia, particularly those where a palliative care approach is appropriate. | Qualitative and quantitative survey (The survey tool uses a combination of Likert-type scales and open-ended questions) | In a private ED | 22 physicians and 44 nurses |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqahtani, A.J.; Mitchell, G. End-of-Life Care Challenges from Staff Viewpoints in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7030083

Alqahtani AJ, Mitchell G. End-of-Life Care Challenges from Staff Viewpoints in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2019; 7(3):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7030083

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqahtani, Ali J., and Geoffrey Mitchell. 2019. "End-of-Life Care Challenges from Staff Viewpoints in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review" Healthcare 7, no. 3: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7030083

APA StyleAlqahtani, A. J., & Mitchell, G. (2019). End-of-Life Care Challenges from Staff Viewpoints in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review. Healthcare, 7(3), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7030083