Effectiveness of a Brief Dietetic Intervention for Hyperlipidaemic Adults Using Individually-Tailored Dietary Feedback

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

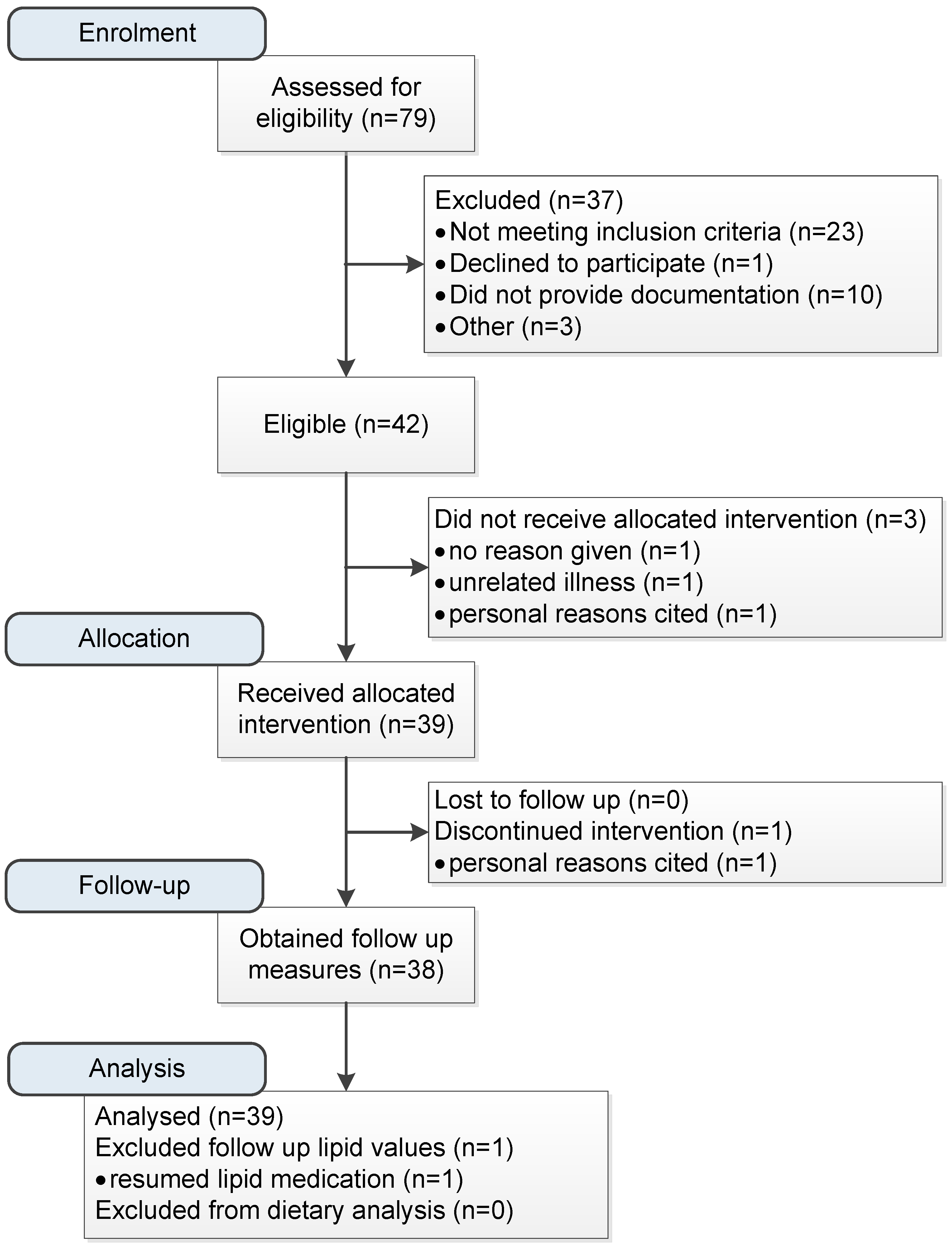

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Dietary Assessments

2.4. Clinical and Anthropometric Assessments

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre, M.L. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Aros, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Gómez-Gracia, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.D.; McDonnell, L.A.; Riley, D.L.; Mark, A.E.; Mosca, L.; Beaton, L.; Papadakis, S.; Blanchard, C.M.; Mochari-Greenberger, H.; O’Farrell, P.; et al. Effect of an intervention to improve the cardiovascular health of family members of patients with coronary artery disease: A randomized trial. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2014, 186, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imes, C.C.; Lewis, F.M. Family history of cardiovascular disease, perceived cardiovascular disease risk, and health-related behavior: A review of the literature. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014, 29, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeroy, S.E.; Cant, R.P. General practitioners’ decision to refer patients to dietitians: Insight into the clinical reasoning process. Aust. J. Prim. Health. 2010, 16, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, O.K.; Estey, E.A.; Zwarenstein, M. Methodologies to evaluate the effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions: A primer for researchers and health care managers. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessels, R.P. Patients’ memory for medical information. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestwich, A.; Kellar, I.; Parker, R.; MacRae, S.; Learmonth, M.; Sykes, B.; Castle, H. How can self-efficacy be increased? Meta-analysis of dietary interventions. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artinian, N.T.; Fletcher, G.F.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Van Horn, L.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Kumanyika, S.; Kraus, W.E.; Fleg, J.L.; Redeker, N.S.; et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 122, 406–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, R.W.; Wing, R.R.; Thorson, C.; Burton, L.R.; Raether, C.; Harvey, J.; Monica, M. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: A randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, N.R.; Sandelowski, M.; Voils, C.I. Spousal support in a behavior change intervention for cholesterol management. Patient. Educ. Couns. 2013, 92, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Jones, P.J.; Lamarche, B.; Kendall, C.W.; Faulkner, D.; Cermakova, L.; Gigleux, I.; Ramprasath, V.; De Souza, R.; Ireland, C.; et al. Effect of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods given at 2 levels of intensity of dietary advice on serum lipids in hyperlipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011, 306, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.E.; Boggess, M.M.; Watson, J.F.; Guest, M.; Duncanson, K.; Pezdirc, K.; Rollo, M.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Burrows, T.L. Reproducibility and comparative validity of a food frequency questionnaire for Australian adults. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, T.L.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Boggess, M.M.; Guest, M.; Collins, C.E. Fruit and vegetable intake assessed by food frequency questionnaire and plasma carotenoids: A validation study in adults. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3240–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, P.S.; Hama, M.Y.; Guilkey, D.K.; Popkin, B.M. Weekend eating in the United States is linked with greater energy, fat, and alcohol intake. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.; Erens, B.; Bates, B.; Church, S.; Boshier, T. Protocol for the Completion of a Food Consumption Record: Individual 24-Hour Recall London: King’s College. Available online: http://dapa-toolkit.mrc.ac.uk/documents/en/24h/24hr_Protocol_LIDNS.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2014).

- Human Nutrition Research Centre. Nutrition in the Newcastle 85+ Study: Overview of the 24hr Multiple Pass Recall United Kingdom. Available online: http://dapa-toolkit.mrc.ac.uk/documents/en/Tra/Training_day_-_24hr_multiple_pass_recall.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2014).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011–2013 Food Nutrient Database File. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/ausnutdatafiles/Pages/foodnutrient.aspx (accessed on 11 May 2016).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011–2013 Food Measures Database File. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/ausnutdatafiles/Pages/foodmeasures.aspx (accessed on 11 May 2016).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Users Guide, 2011–2013—Discretionary Food List, 1st ed.Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- StataCorp LP. Stata/IC 13.1 for Windows; StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjostram, M.; Ainsworth, B.; Bauman, A. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Short and Long Forms. Available online: www.ipaqkise/scoring (accessed on 11 May 2009).

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychol. Health. 2000, 15, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines, 1st ed.National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, K.; Hartley, L.; Flowers, N.; Clarke, A.; Hooper, L.; Thorogood, M.; Strange, S. ‘Mediterranean’ dietary pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Tong, T.Y.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khandelwal, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; Mozaffarian, D.; de Lorgeril, M. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Views from experts around the world. BioMed. Cent. 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. Available online: http://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/australian-guide-healthy-eating (accessed on 3 November 2014).

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Faulkner, D.A.; Nguyen, T.; Kemp, T.; Marchie, A.; Wong, M.W.; De Souza, R.; Emam, A.; Vidgen, E.; et al. Assessment of the longer-term effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods in hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tonkin, A.; Barter, P.; Best, J.; Boyden, A.; Furler, J.; Hossack, K.; Sullivan, D.; Thompson, D.; Vale, M.; Cooper, C.; et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Position statement on lipid management—2005. Heart Lung Circ. 2005, 14, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pathology North. LabInfo Test Directory. Available online: http://www.palms.com.au/php/labinfo/index.php?site=JHH (accessed on 21 May 2015).

- Hines, G.; Kennedy, I.; Holman, R. HOMA 2 Calculator, 1st ed.; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: Meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012, 380, 581–590. [Google Scholar]

- Chiuve, S.E.; Fung, T.T.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; McCullough, M.L.; Wang, M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetke, L.M.; Stuart, M.A.; Truszczynska, H. A single nutrition counseling session with a registered dietitian improves short-term clinical outcomes for rural Kentucky patients with chronic diseases. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, J.; Nilsson, A.; Johansson, M.; Ekesbo, R.; Aberg, A.M.; Johansson, U.; Björck, I. A diet based on multiple functional concepts improves cardiometabolic risk parameters in healthy subjects. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Mirrahimi, A.; Srichaikul, K.; Berryman, C.E.; Wang, L.; Carleton, A.; Abdulnour, S.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Kendall, C.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Soy protein reduces serum cholesterol by both intrinsic and food displacement mechanisms. J. Nutr. 2010, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzano, L.A. Effects of soluble dietary fiber on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary heart disease risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2008, 10, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patch, C.S.; Tapsell, L.C.; Williams, P.G.; Gordon, M. Plant sterols as dietary adjuvants in the reduction of cardiovascular risk: Theory and evidence. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2006, 2, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Food and Nutrients, 2011—2012, 1st ed.Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Health Do, 1st ed.Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Vuksan, V.; Jenkins, A.L.; Rogovik, A.L.; Fairgrieve, C.D.; Jovanovski, E.; Leiter, L.A. Viscosity rather than quantity of dietary fibre predicts cholesterol-lowering effect in healthy individuals. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Hartman, T.J.; Curran, J.M. Consumption of dry beans, peas, and lentils could improve diet quality in the US population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.B.; Matthiessen, J.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Tetens, I. Characteristics of misreporters of dietary intake and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. Women and Heart Disease Forum Report, 1st ed.; National Heart Foundation of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Chronic Diseases, 2011–2012, 1st ed.Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

| Dietary Knowledge | Quantity | Example Foods |

| Nuts | 25–30g/day | Unsalted almonds, walnuts |

| Fish and omega 3 fats | 2–3 serves/week | Fresh/canned salmon or tuna |

| Soy proteins | Up to 7 serves/day | Soy milk, tofu, tempeh |

| Lentils and legumes | Up to 7 serves/week | Kidney beans, lentils, chick peas |

| Soluble fibre | Up to 15g/day | Psyllium husk, oat bran, fruit, vegetables |

| Plant sterols | 2–3 serves/day | Margarines/milk/cheese with added sterols |

| Healthy eating | As given by the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating [31] | |

| Behavioural technique [32] | Illustration from intervention | |

| Provide information about behaviour-health link | General information given about the types of foods and nutrients that increase blood triglyceride levels | |

| Prompt intention formation | Participants were provided with pantry items of recommended foods and recipes for their use | |

| Prompt specific goal setting | Participants were required to generate three specific personal goals | |

| Provide instruction | All participants were provided with 63-page resource manual with recommended serving sizes of food groups and food preparation methods | |

| Model or demonstrate the behaviour | Study participants were given breakfast upon completion of fasting study measures, with choices offered from a menu of items consistent with the recommended dietary advice | |

| Provide feedback on performance | Participants were given dietary feedback based on analysis of current intake | |

| Risk Factors | (Reference Range 1) | Baseline (n = 39) | Follow up (n = 38) | Change | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometry | |||||||

| BMI | (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.7 | 27.6 ± 5.7 | −0.4 | −0.7, −0.2 | <0.01 | |

| Weight | (kg) | 77.8 ± 17.6 | 76.3 ± 17.5 | −1.3 | −1.9, −0.7 | <0.01 | |

| Waist circumference | (cm) | 92.3 ± 15.9 | 90.2 ± 14.5 | −1.5 | −2.3, −0.7 | <0.01 | |

| Blood pressure 2 | (mmHg) | ||||||

| Brachial | |||||||

| Systolic | 125.9 ± 17.2 | 121.1 ± 16.0 | −4.8 | −8.3, −1.2 | <0.01 | ||

| Diastolic | 75.9 ± 7.3 | 73.2 ± 8.6 | −2.4 | −4.1, −0.7 | < 0.01 | ||

| Central | |||||||

| Systolic | 120.2 ± 17.0 | 116.6 ± 14.7 | −3.6 | −7.5, 0.2 | 0.07 | ||

| Diastolic | 77.2 ± 7.3 | 75.0 ± 8.7 | −2.0 | −4.0, 0.4 | 0.06 | ||

| Augmentation index | 108.4 ± 56.8 | 99.8 ± 34.8 | −9.6 | −23.1, 3.9 | 0.16 | ||

| Fasting Serum CVD risk markers 3 | |||||||

| Lipids | |||||||

| Triglycerides | < 1.5 | (mmol/L) | 1.60 ± 1.27 | 1.19 ± 0.51 | −0.38 | −0.73, −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Total cholesterol | < 4.00 | (mmol/L) | 6.79 ± 1.10 | 6.27 ± 1.00 | −0.51 | −0.77, −0.24 | <0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol | < 2.5 | (mmol/L) | 4.60 ± 1.04 | 4.30 ± 0.97 | −0.29 | −0.52, −0.05 | 0.02 |

| HDL cholesterol | > 1.0 | (mmol/L) | 1.46 ± 0.34 | 1.43 ± 0.35 | −0.05 | −0.10, −0.00 | 0.05 |

| Total:HDL ratio | 5.02 ± 1.96 | 4.63 ± 1.44 | −0.27 | −0.51, −0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| Inflammation markers | |||||||

| hsCRP | < 5.0 | (mg/L) | 2.25 ± 2.26 | 2.22 ± 2.23 | 0.1 | −0.40, 0.60 | 0.70 |

| ALT | 0–45 | (U/L) | 25.9 ± 15.1 | 27.8 ± 14.7 | 2.0 | −0.1, 4.1 | 0.07 |

| AST | 0–41 | (U/L) | 25.9 ± 5.9 | 27.6 ± 7.1 | 1.9 | −0.5, 4.2 | 0.12 |

| GGT | 0–45 (F) 0–70 (M) | (U/L) | 32.5 ± 37.0 | 30.1 ± 29.5 | −1.1 | −5.2, 3.1 | 0.62 |

| BGL | 3.0–6.0 | (mmol/L) | 5.16 ± 0.57 | 4.94 ±0.59 | −0.20 | −0.32, −0.08 | <0.01 |

| HOMA IR score 4 | (mmol/L) | 1.04 ± 0.74 | |||||

| Baseline (n = 39) | Follow up (n = 38) | Change 1 | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy (kJ/day) | 9580 ± 2695 | 8712 ± 2614 | −870 | −1611, −130 | 0.02 |

| Discretionary energy (kJ/day) 2 | 3231 ± 2058 | 2223 ± 1821 | −1006 | −1563, −450 | <0.001 |

| % Discretionary energy | 31.7 ± 16.6 | 24.1 ± 15.1 | −7.5 | −12.4, −2.7 | < 0.01 |

| % Protein | 17.4 ± 4.4 | 18.9 ± 4.6 | 1.5 | 0.1, 2.9 | 0.04 |

| % CHO | 45.0 ± 10.0 | 43.6 ± 9.9 | −1.4 | −4.4, 1.6 | 0.35 |

| % Fats | 33.6 ± 8.7 | 32.9 ± 9.7 | −0.7 | −3.7, 2.3 | 0.64 |

| % sat. fat | 11.4 ± 4.0 | 9.8 ± 4.5 | −1.5 | −2.9, −0.2 | 0.03 |

| % mono. fat | 13.5 ± 5.2 | 12.9 ± 5.2 | −0.6 | −2.4, 1.2 | 0.50 |

| % poly. fat | 6.0 ± 2.9 | 7.2 ± 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.46, 2.1 | <0.01 |

| Fibre (g) | 29.2 ± 10.2 | 29.3 ± 10.0 | 0.1 | −2.2, 2.5 | 0.91 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2764 ± 1397 | 2410 ± 1184 | −358 | −650, −67 | 0.02 |

| Foods specific to cardiovascular health | |||||

| Fruit serves/day 3 | 0.85 ± 0.89 | 0.97 ± 99 | 0.12 | −0.13, 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Vegetable serves/day 3 | 3.18 ± 2.83 | 3.05 ± 2.47 | −0.13 | −0.80, 0.53 | 0.69 |

| Nuts (g/day) | 16.3 ± 32.3 | 17.6 ± 25.6 | 1.2 | −7.7, 10.2 | 0.79 |

| Fish (g/day) | 29.4 ± 62.9 | 44.0 ± 68.4 | 13.5 | −5.4, 32.5 | 0.16 |

| Soy proteins (g/day) 4 | 1.0 ± 2.9 | 2.9 ± 4.3 | 2.0 | 0.8, 3.3 | 0.001 |

| Legumes (g/day) | 8.3 ± 28.0 | 20.9 ± 54.4 | 12.6 | −0.53, 25.8 | 0.06 |

| Fibre from oats/psyllium/linseed (g/day) 5 | 1.7 ± 3.0 | 2.4 ± 3.5 | 0.6 | −0.4, 1.6 | 0.21 |

| Plant sterols (mg/day) | 257 ± 582 | 604 ± 885 | 343 | 74, 611 | 0.01 |

| Baseline | Follow up | Χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n = 39) | % (n = 38) 1 | p Value (Pearsons) | |

| Type of milk normally consumed | |||

| Don’t drink milk | 7.7 (n = 3) | 7.7 (n = 3) | 0.08 |

| Normal/whole/full cream | 15.4 (n = 6) | 2.6 (n = 1) | |

| Reduced fat | 53.9 (n = 21) | 41.0 (n = 16) | |

| Skim | 12.8 (n = 5) | 15.4 (n = 6) | |

| Soy | 7.7 (n = 3) | 30.8 (n = 12) | |

| Other/Not sure | 2.6 (n = 1) | 2.6 (n = 1) | |

| Type of cheese normally eaten | |||

| Don’t eat cheese | 5.1 (n = 2) | 5.1 (n = 2) | <0.01 |

| Normal/full fat | 56.4 (n = 22) | 20.5 (n = 8) | |

| Reduced fat | 28.2 (n = 11) | 43.6 (n = 17) | |

| Low fat | 10.3 (n = 4) | 30.8 (n = 12) | |

| Type of meat | |||

| Don’t eat meat | 5.1 (n = 2) | 5.1 (n = 2) | 0.52 |

| Normal/untrimmed | 38.5 (n = 15) | 23.1 (n = 9) | |

| Reduced fat/semi-trimmed | 35.9 (n = 14) | 43.6 (n = 17) | |

| Low fat/fully-trimmed | 20.5 (n = 8) | 28.2 (n = 11) | |

| Type of chicken | |||

| Fried | 2.6 (n = 1) | 0 (n = 0) | 0.38 |

| Crumbed | 2.6 (n = 1) | 0 (n = 0) | |

| With skin | 20.5 (n = 8) | 12.8 (n = 5) | |

| Skin removed | 74.4 (n = 29) | 87.2 (n = 34) | |

| Adding salt to food | |||

| Never add salt | 43.6 (n = 17) | 51.2 (n = 20) | 0.56 |

| During cooking | 23.1 (n = 9) | 23.1 (n = 9) | |

| To meals | 23.1 (n = 9) | 23.1 (n = 9) | |

| Both meals and cooking | 10.3 (n = 4) | 2.6 (n = 1) | |

| Purchasing salt-reduced foods | |||

| Never | 18.0 (n = 7) | 12.8 (n = 5) | 0.12 |

| Sometimes | 66.7 (n = 26) | 51.3 (n = 20) | |

| Always | 15.4 (n = 6) | 35.9 (n = 14) | |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schumacher, T.L.; Burrows, T.L.; Rollo, M.E.; Spratt, N.J.; Callister, R.; Collins, C.E. Effectiveness of a Brief Dietetic Intervention for Hyperlipidaemic Adults Using Individually-Tailored Dietary Feedback. Healthcare 2016, 4, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040075

Schumacher TL, Burrows TL, Rollo ME, Spratt NJ, Callister R, Collins CE. Effectiveness of a Brief Dietetic Intervention for Hyperlipidaemic Adults Using Individually-Tailored Dietary Feedback. Healthcare. 2016; 4(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchumacher, Tracy L., Tracy L. Burrows, Megan E. Rollo, Neil J. Spratt, Robin Callister, and Clare E. Collins. 2016. "Effectiveness of a Brief Dietetic Intervention for Hyperlipidaemic Adults Using Individually-Tailored Dietary Feedback" Healthcare 4, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040075

APA StyleSchumacher, T. L., Burrows, T. L., Rollo, M. E., Spratt, N. J., Callister, R., & Collins, C. E. (2016). Effectiveness of a Brief Dietetic Intervention for Hyperlipidaemic Adults Using Individually-Tailored Dietary Feedback. Healthcare, 4(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040075