Postpartum Bonding Disorder: Factor Structure, Validity, Reliability and a Model Comparison of the Postnatal Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese Mothers of Infants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bonding Disorder

2.2.2. Depression

2.2.3. Neonatal Abuse

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the PBQ Items

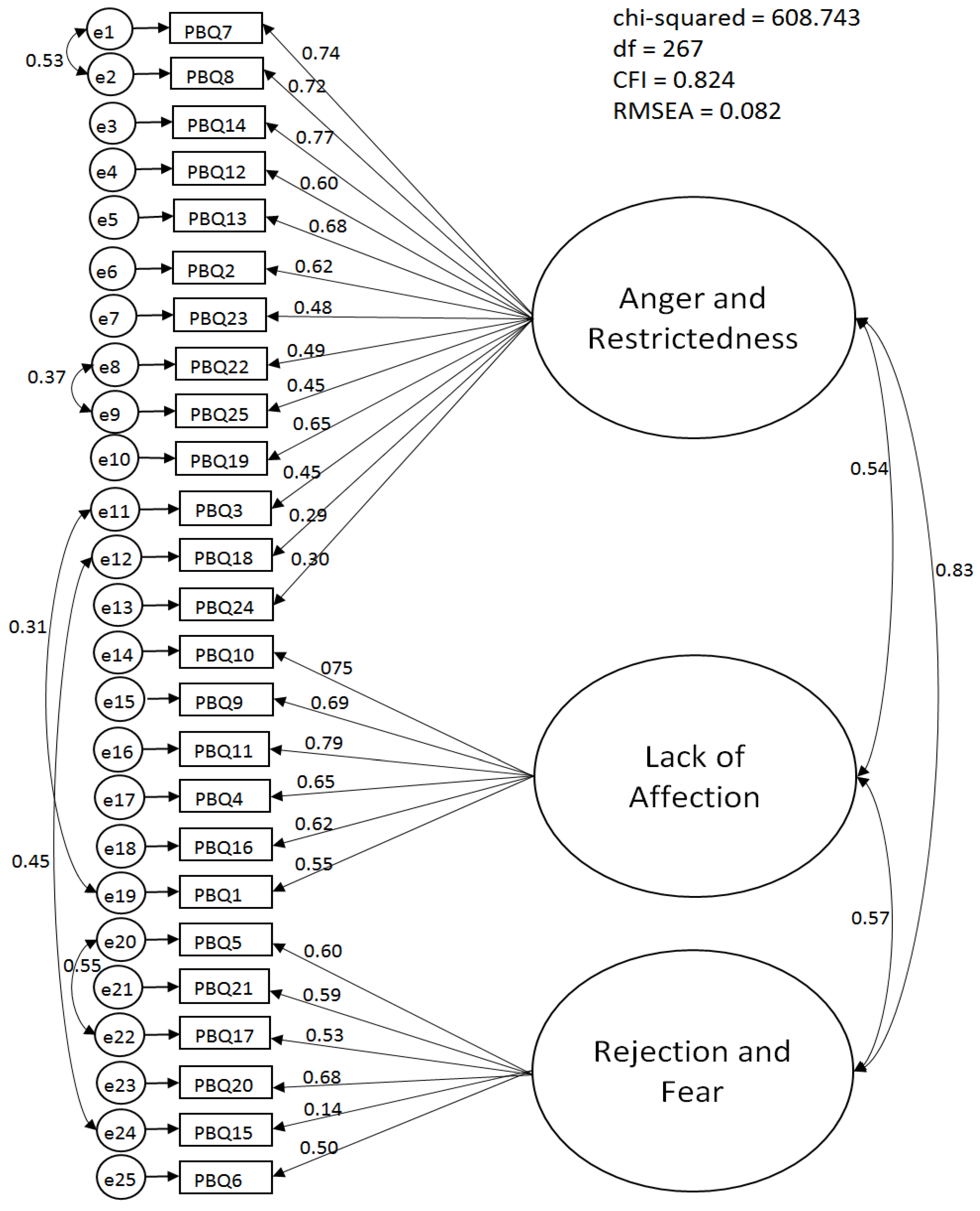

3.2. Factor Structure of the PBQ

3.3. Test–Retest Reliability

3.4. Construct Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brockington, I.F. Diagnosis and management of post-partum disorders: A review. World Psychiatr. 2004, 3, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brockington, I.F. Maternal rejection of the young child: Present status of the clinical syndrome. Psychopathology 2011, 44, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.C. “Anybody’s child”: Severe disorders of mother-to-infant bonding. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1997, 171, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhborg, M.; Matthiesen, A.S.; Lundh, W.; Widström, A.M. Some early indicators for depressive symptoms and bonding 2 months postpartum: A study of new mothers and fathers. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2005, 8, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edhborg, M.; Nasreen, H.E.; Kabir, Z.N. Impact of postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms on mothers’ emotional tie to their infants 2–3 months postpartum: A population-based study from rural Bangladesh. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2011, 14, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honjo, S.; Arai, S.; Kaneko, H.; Ujiie, T.; Murase, S.; Sechiyama, H.; Inoko, K. Antenatal depression and maternal-fetal attachment. Psychopathology 2003, 36, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klier, C.M. Mother-infant bonding disorders in patients with postnatal depression: The Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire in clinical practice. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubu, M.; Okano, T.; Sugiyama, T. Postnatal depression, maternal bonding failure, and negative attitudes towards pregnancy: A longitudinal study of pregnant women in Japan. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2012, 15, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moehler, E.; Brunner, R.; Wiebel, A.; Reck, C.; Resch, F. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, M.; Nagai, Y.; Sobajima, H.; Ando, T.; Honjo, S. Depression in the mother and maternal attachment: Results from a follow-up study at 1 year postpartum. Psychopathology 2003, 36, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, M.; Nagai, Y.; Sobajima, H.; Ando, T.; Nishide, Y.; Honjo, S. Maternity blues and attachment to children in mothers of full-term normal infants. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Sakanashi, K.; Tanaka, T. Jido gyakutai no genin wa sango no yokuutsu de wa naku bondingu shougai de aru: Kumamoto chiku no jyudan chousa kara (A cause of the neonatal abuse was the bonding disorders not postpartum depression: A longitudinal study in Kumamoto prefecture). In Proceedings of the Poster Session on the 11th Academic Meeting of the Japanese Society of Perinatal Mental Health, Omiya, Japanese, 13 November 2014. (In Japanese)

- Condon, J.T.; Corkindale, C. The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: Development of a self-report questionnaire measurement. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1998, 16, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayler, A.; Atkins, R.; Kumar, R.; Adams, D.; Glover, V. A new mother-to-infant bonding scale: Links with early maternal mood. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2005, 8, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, I.F.; Oats, J.; George, S.; Turner, D.; Vostanis, P.; Sullivan, M.; Murdoch, C. A screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2001, 3, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bussel, J.C.H.; Spitz, B.; Demyttenaere, K. Three self-report questionnaires of the early mother-to-infant bond: Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the MPAS, PBQ and MIBS. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2010, 13, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, I.F.; Aucamp, H.M.; Fraser, C. Severe disorders of the mother-infant relationship: Definition and frequency. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, I.F.; Fraser, C.; Wilson, D. The postpartum bonding questionnaire: A validation. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittkowski, A.; Wiek, A.; Mann, S. An evaluation of two bonding questionnaires: A comparison of the mother-to-infant bonding scale with the postpartum bonding questionnaire in a sample of primiparous mothers. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2007, 10, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, C.; Klier, C.M.; Pabst, K.; Stehle, E.; Steffenelli, U.; Struben, K.; Backenstrass, M. The German version of the postpartum Bonding Instrument: Psychometric properties and association with postpartum depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, H.; Honjo, S. The psychometric properties and factor structure of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese mothers. Psychology 2014, 5, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetsugu, Y.; Honjo, S.; Ikeda, M.; Kamibeppu, K. The Japanese version of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire: Examination of the reliability, validity, and scale structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report 2012–2013 (Summary), 2013. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw7/dl/summary.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2016).

- Kaneko, H. Early Intervention and Support System for Postpartum Depression and Postpartum Bonding Disorders. Report No. 21730547. Available online: https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/file/KAKENHI-PROJECT-21730547/21730547seika.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2013). (In Japanese)

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Masuji, F.; Tamaki, R.; Nomura, J.; Murata, M.; Miyaoka, H.; Kitamura, T. Validation and reliability of Japanese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Arch. Psychiatr. Diagnos. Clin. Eval. 1996, 7, 525–533. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L. Measuring Physical and Psychological Maltreatment of Children with the Conflict Tactics Scales. In Manual for the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS) and Test Forms for the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwick, W.R.; Velicer, W.F. Factors influencing four rules for determining the number of components to retain. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1982, 17, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermelleh-Engell, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Method. Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, T.; Ohashi, Y.; Kita, S.; Haruna, M.; Kubo, R. Depressive mood, bonding failure, and abusive parenting among mothers with three-month-old babies in a Japanese community. Open J. Psychiatr. 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins, M.; Roberts, I.S.J.; Glover, V.; Taylor, A. Mother-child bonding at 1 year: Associations with symptoms of postnatal depression and bonding in the first few weeks. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013, 16, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Yamashita, H.; Conroy, S.A. Japanese version of Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: Factor structure, longitudinal changes and links with maternal mood during the early postnatal period in Japanese mothers. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2012, 15, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraiberg, S.; Adelson, E.; Shapiro, V. Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 1975, 14, 387–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H. Nyu-yo-ji seisin hoken no atarasii doukou (The new trend of infant mental health). In Nyu-yo-ji Seisin Hoken No Atarasii Kaze (The New Tide of Infant Mental Health); Watanabe, H., Hashimoto, Y., Eds.; Minervashobo: Kyoto, Japan, 2001; pp. 2–11. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Slade, A.; Cohen, L.J.; Sadler, L.J.; Miller, M. The psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy. In Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 3rd ed.; Zeanah, C.H., Jr., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

| Item Number | PBQ Items | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Skewness after Log Transformation | Commu-nality | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||||||

| 7 | My baby winds me up | 0.81 (0.81) | 0.4 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.83 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| 8 | My baby irritates me | 0.88 (0.82) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.56 | 0.78 | −0.09 | −0.02 |

| 14 | I feel angry with my baby | 0.32 (0.54) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.58 | 0.70 | −0.08 | 0.16 |

| 12 | My baby cries too much | 1.15 (1.13) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.07 | −0.21 |

| 13 | I feel trapped as a mother | 1.08 (1.20) | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 2 | I wish the old days when I had no baby would come back | 0.55 (0.73) | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| 23 | I feel the only solution is for someone else to look after my baby | 0.85 (0.96) | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 22 | I feel confident when changing my baby | 2.14 (1.44) | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.10 | −0.06 |

| 25 | My baby is easily comforted | 1.99 (1.22) | 0.2 | −0.5 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.14 | −0.07 |

| 19 | My baby makes me anxious | 0.40 (0.70) | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| 3 | I feel distant from my baby | 0.45 (0.99) | 2.9 | 1.7 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| 18 | I have done harmful things to my baby | 0.03 (0.17) | 5.7 | 7.9 | 0.12 | 0.27 | −0.10 | 0.16 |

| 24 | I feel like hurting my baby | 0.01 (0.08) | 13.1 | 6.0 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| 10 | I love my baby to bits | 0.32 (0.78) | 3.5 | 2.0 | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.92 | −0.09 |

| 9 | I feel happy when my baby smiles or laughs | 0.15 (0.66) | 5.8 | 4.8 | 0.57 | −0.23 | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| 11 | I enjoy playing with my baby | 0.40 (0.81) | 2.6 | 1.8 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.76 | −0.03 |

| 4 | I love to cuddle my baby | 0.27 (0.80) | 4.3 | 2.5 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.54 | 0.04 |

| 16 | My baby is the most beautiful baby in the world | 0.37 (0.85) | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.06 |

| 1 | I feel close to my baby | 0.28 (0.61) | 2.5 | 1.86 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.18 |

| 5 | I regret having this baby | 0.03 (0.21) | 6.8 | 4.70 | 0.75 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.91 |

| 21 | My baby annoys me | 0.08 (0.33) | 4.4 | 3.36 | 0.68 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.84 |

| 17 | I wish my baby would somehow go away | 0.02 (0.13) | 7.4 | 4.93 | 0.58 | −0.14 | 0.13 | 0.76 |

| 20 | I am afraid of my baby | 0.05 (0.28) | 7.9 | 3.66 | 0.32 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.58 |

| 15 | I resent my baby | 0.05 (0.21) | 4.4 | 8.25 | 0.26 | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.42 |

| 6 | The baby does not seem to be mine | 0.17 (0.67) | 5.4 | 2.22 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.26 |

| Goodness of Fit Indices | Three-Factor Model Derived from the EFA in This Study | Four-Factor Model by Brockington et al. | One-Factor Model by Kaneko and Honjo | Four-Factor Model by Suetsugu et al. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN | 608.74 | 1043.20 | 409.99 | 172.44 |

| Df | 267 | 270 | 104 | 71 |

| CMIN/df | 2.28 | 3.86 | 3.94 | 2.43 |

| CFI | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| RMSEA | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| AIC | 724.74 | 1153.2 | 473.99 | 240.44 |

| PBQ Subscales | 1 Month After Childbirth | 5 Days After Childbirth | ICC | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Anger and Restrictedness | 10.24 (6.92) | 9.13 (6.46) | 0.83 | 6.11 *** |

| Lack of Affection | 1.69 (3.37) | 1.85 (3.52) | 0.82 | 5.69 *** |

| Rejection and Fear | 0.49 (1.41) | 0.49 (1.35) | 0.76 | 4.21 *** |

| Instruments | Mean (SD) | PBQ Subscales | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anger and Restrictedness | Lack of Affection | Rejection and Fear | ||

| EPDS | 3.07 (3.28) | 0.49 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.32 ** |

| Psychological abuse | 8.01 (2.13) | 0.45 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.31 ** |

| Physical abuse | 9.00 (0.05) | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohashi, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Sakanashi, K.; Tanaka, T. Postpartum Bonding Disorder: Factor Structure, Validity, Reliability and a Model Comparison of the Postnatal Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese Mothers of Infants. Healthcare 2016, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030050

Ohashi Y, Kitamura T, Sakanashi K, Tanaka T. Postpartum Bonding Disorder: Factor Structure, Validity, Reliability and a Model Comparison of the Postnatal Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese Mothers of Infants. Healthcare. 2016; 4(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhashi, Yukiko, Toshinori Kitamura, Kyoko Sakanashi, and Tomoko Tanaka. 2016. "Postpartum Bonding Disorder: Factor Structure, Validity, Reliability and a Model Comparison of the Postnatal Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese Mothers of Infants" Healthcare 4, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030050

APA StyleOhashi, Y., Kitamura, T., Sakanashi, K., & Tanaka, T. (2016). Postpartum Bonding Disorder: Factor Structure, Validity, Reliability and a Model Comparison of the Postnatal Bonding Questionnaire in Japanese Mothers of Infants. Healthcare, 4(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030050