Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the MOS Pain Effect Scale in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Sample

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Phase 1: Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process

- Forward and Back-Translation: Initially, two forward translations (T1 and T2) of the English PES into Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) were conducted by two independent bilingual translators (both fluent in English and Arabic), one with a medical background and the other without. These forward translations (T1 and T2) were subsequently consolidated into a single Arabic version (T-12) by a professional translator and a medical specialist to address any discrepancies. The synthesized Arabic version was then subjected to a back-translation process into English, where two independent bilingual translators, who had no prior knowledge of the PES, translated it back into English to produce two comparative versions (BT1 and BT2).

- Expert Committee Review: In line with COSMIN guidelines, once the translation process was completed, the Arabic version of Pain Effects Scale (PES-Ar) was evaluated by a panel of ten independent experts, consisting of ten healthcare professionals, including methodologists, medical faculty, neurorehabilitation clinicians, and linguistics and translation specialists. The committee reviewed both the English and Arabic versions to assess face and content validity of each item individually and produced the pre-final version of the PES-Ar. The clarity and relevance of each item were assessed using two separate four-point Likert scales: one for relevance (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant), and another for clarity (1 = not clear, 2 = item needs some revision, 3 = clear but needs minor revision, 4 = very clear). Experts were asked to assign a score from 1 to 4 for each item on both dimensions. For the relevance assessment, scores of 3 or 4 were recorded as 1 (indicating acceptable relevance), and scores of 1 or 2 were recorded as 0. Based on these ratings, the Content Validity Index (CVI) for each item (I-CVI) was computed by dividing the number of experts who rated the item as 3 or 4 by the total number of experts [42]. The Scale-Level CVI (S-CVI) was also calculated to reflect the overall content validity of the instrument [43]. To attain satisfactory content validity, an S-CVI/Avg score of at least 0.83 is required [44]. The committee ensured that conceptual equivalence was maintained and that the items were culturally relevant to the target population.

- Cognitive Debriefing and Pilot Testing: To obtain qualitative feedback, a pilot study was conducted with 20 individuals with MS using a structured cognitive debriefing approach. Face-to-face interviews were carried out, during which probing questions were used to assess participants’ understanding of each item (e.g., “In your own words, what does this item ask?”). Participants were also invited to share their experiences and perceptions of the current version of the questionnaire, and all feedback was systematically recorded. Based on the findings of this process, the PES-Ar was finalized.

- Cultural Adaptation: Based on expert feedback and pilot testing, culturally specific expressions were adjusted (culturally adapted) to ensure appropriate understanding.

2.4.2. Phase 2: Validity and Reliability Process

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.5.1. Pain Effects Scale

2.5.2. The Arabic Version of the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ)

2.5.3. The Arabic Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

2.5.4. The Arabic Version of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS)

2.5.5. The Arabic Version of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29)

2.5.6. The Global Rating of Change (GROC)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Floor and Ceiling Effect

2.6.2. Test–Retest Reliability and Internal Consistency

2.6.3. Content, Structural and Construct Validity

2.6.4. Sample Size Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

3.1.1. Demographic Data and Characteristics of the Participants

3.1.2. Floor and Ceiling Effects

3.2. Phase 2: Validity and Reliability Process

3.2.1. Internal Consistency and Test–Retest Reliability

3.2.2. Measurement Error

3.2.3. Validity Process

Face, Content Validity

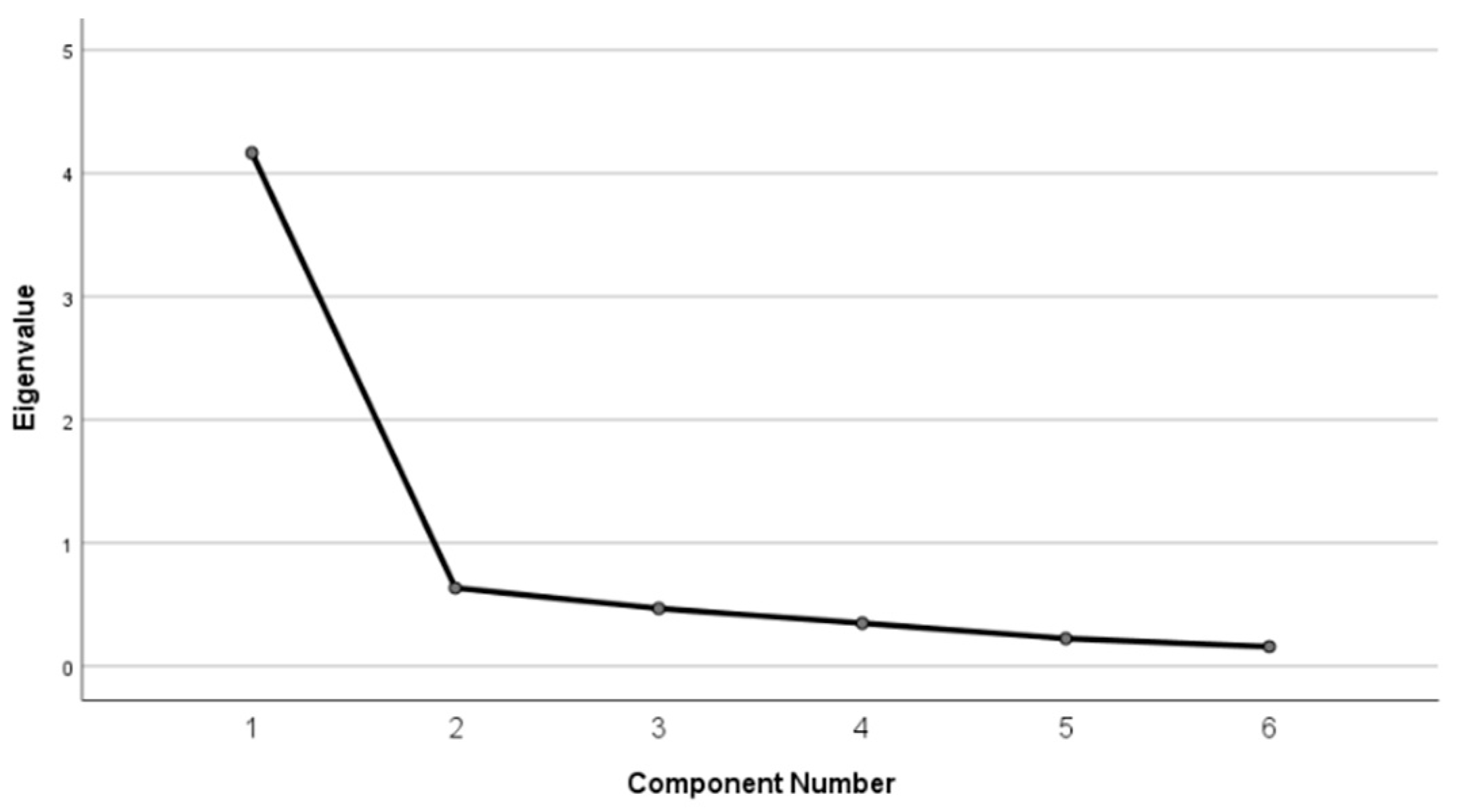

Structural Validity

Construct Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| RR | Relapsing-Remitting |

| SP | Secondary-Progressive |

| PES | Pain Effects Scale |

| PES-Ar | Arabic Version of the Pain Effects Scale |

| SF-MPQ | Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| MFIS | Modified Fatigue Impact Scale |

| MSIS-29 | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29 |

| GROC | Global Rating of Change |

| MOCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MSQLI | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SEM | Standard Error of Measurement |

| MDC95 | Minimal Detectable Change (95% CI) |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| I-CVI | Item-Level Content Validity Index |

| S-CVI | Scale-Level Content Validity Index |

| KS | Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| KKUH | King Khalid University Hospital |

Appendix A

| Instrument | Higher Score Indicates |

|---|---|

| PES-Ar (Pain Effects Scale—Arabic) | Greater pain interference with daily activities and participation |

| MSIS-29 Physical subscale | Greater physical impact of multiple sclerosis |

| MSIS-29 Psychological subscale | Greater psychological impact of multiple sclerosis |

| PHQ-9 | More severe depressive symptoms |

| MFIS | Greater fatigue impact |

| SF-MPQ | Greater pain intensity |

| Original English Item | Initial Arabic Translation | Final Arabic Translation (PES-Ar) | Modification Made | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mood | الحالة المزاجية | حالتك المزاجية | Added the possessive pronoun “ك” (your mood) | To enhance the personal nature of the item, directly referring to the respondent’s mood, thereby increasing the clarity of self-assessment. |

| ability to walk or move around | القدرة على المشي أو التحرك | قدرتك على المشي أو التحرك | Added the possessive pronoun “ك” (your ability) | To enhance the personal nature of the item, directly referring to the respondent’s ability to walk or move around, thereby increasing the clarity of self-assessment. |

| sleep | النوم | نومك | Added the possessive pronoun “ك” (your sleep) | To enhance the personal nature of the item, directly referring to the respondent’s sleep, thereby increasing the clarity of self-assessment. |

| normal work (both outside your home and at home) | العمل الطبيعي (سواء خارج المنزل أو داخله) | عملك المعتاد (سواء من المنزل أو خارجه) | 1. Changed “العمل الطبيعي” (normal work) to “عملك المعتاد” (your usual work). 2. Reordered “خارج المنزل أو داخله” (outside or inside the home) to “من المنزل أو خارجه” (from home or outside). | 1. The word “المعتاد” (usual) is more culturally appropriate and better describes daily routine than “الطبيعي” (normal), which might carry judgmental connotations. 2. Reordering the phrase makes it more fluid and natural in Arabic. |

| recreational activities | الأنشطة الترفيهية | أنشطتك الترفيهية | Added the possessive pronoun “ك” (your activities) | To enhance the personal nature of the item, directly referring to the respondent’s recreational activities, thereby increasing the clarity of self-assessment. |

| enjoyment of life | الاستمتاع بالحياة | قدرتك على الاستمتاع بحياتك | Changed to ‘قدرتك على الاستمتاع بحياتك’ (your ability to enjoy your life) by adding the phrase ‘your ability’ and using the possessive form ‘your life’. | The item was rephrased to emphasize the individual’s ‘ability’ to enjoy life, making it more action-oriented and personally relevant. This modification enhances the clarity of the item in the Arabic context, ensuring that respondents focus on the functional impact of pain on their quality of life rather than a general abstract concept |

References

- Calabresi, P.A. Diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis. Am. Fam. Physician 2004, 70, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kasper, D.; Fauci, A.; Hauser, S.; Longo, D.; Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tafti, D.; Ehsan, M.; Xixis, K.L. Multiple sclerosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499849/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- AlJumah, M.; Bunyan, R.; Al Otaibi, H.; Al Towaijri, G.; Karim, A.; Al Malik, Y.; Kalakatawi, M.; Alrajeh, S.; Al Mejally, M.; Algahtani, H.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Saudi Arabia, a descriptive study. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS, 3rd ed.; Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (MSIF): London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.msif.org/news/2023/08/21/new-prevalence-and-incidence-data-now-available-in-the-atlas-of-ms/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Kingwell, E.; Marriott, J.J.; Jetté, N.; Pringsheim, T.; Makhani, N.; Morrow, S.A.; Fisk, J.D.; Evans, C.; Béland, S.G.; Kulaga, S.; et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Europe: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajashi, H.; Wali, A.; Aqeeli, A.; Magboul, A.; Alfulayt, M.; Baasher, A.; Alzahrani, S. The Prevalence of Comorbidities Associated with Multiple Sclerosis in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Afr. Med. 2024, 23, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, A.; Almutairi, H.; Alnasser, G.; Alsoina, S.; Aljaber, N. Direct Medical Costs Associated with Multiple Sclerosis in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Single-Center Cost of Illness Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagnew, B.; Campbell, J.A.; Laslett, L.L.; Honan, C.A.; Lefever, K.; Taylor, B.V.; Saul, A.; van der Mei, I. Understanding pain types and the lived experiences of individuals with multiple sclerosis and pain: A mixed methods study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 104, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.; Whibley, D.; Alschuler, K.; Ehde, D.; Williams, D.; Clauw, D.; Braley, T. Characterizing chronic pain phenotypes in multiple sclerosis: A nationwide survey study. Pain 2020, 162, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, D.; Plantone, D.; Morselli, F.; Dallari, G.; Simone, A.; Vitetta, F.; Sola, P.; Primiano, G.; Nociti, V.; Pardini, M.; et al. Systematic assessment and characterization of chronic pain in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Amatya, B.; Galea, M.P.; Khan, F. Chronic pain in multiple sclerosis: A 10-year longitudinal study. Scand. J. Pain 2017, 16, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimichael, O.; Kerns, R.D.; Rizzo, M.A.; Cutter, G.; Vollmer, T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain 2007, 127, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehde, D.M.; Jensen, M.P.; Engel, J.M.; Turner, J.A.; Hoffman, A.J.; Cardenas, D.D. Chronic pain secondary to disability: A review. Clin. J. Pain 2003, 19, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.B.; Schwid, S.R.; Herrmann, D.N.; Markman, J.D.; Dworkin, R.H. Pain associated with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and proposed classification. Pain 2008, 137, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alschuler, K.N.; Ehde, D.M.; Jensen, M.P. The co-occurrence of pain and depression in adults with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2013, 58, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, R.A.; Reingold, S.; Cohen, J.; Stuve, O.; Trojano, M.; Sorensen, P.S.; Cutter, G.; Reider, N. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult. Scler. 2015, 21, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkan, M.A.; Gürkan, F.T. Measurement of Pain in Multiple Sclerosis. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars. 2018, 55, S58–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Dineen, K.; Arnason, B.; Reder, A.; Webster, K.A.; Karabatsos, G.; Chang, C.; Lloyd, S.; Mo, F.; Steward, J.; et al. Validation of the functional assessment of multiple sclerosis quality of life instrument. Neurology 1996, 47, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.S.; LaRocca, N.G.; Miller, D.M.; Ritvo, P.G.; Andrews, H.; Paty, D. Recent developments in the assessment of quality of life in multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult. Scler. 1999, 5, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, P.G.; Fischer, J.S.; Miller, D.M.; Andrews, H.; Paty, D.W.; LaRocca, N.G. Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A user’s manual. In National Multiple Sclerosis Society; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- El Alaoui Taoussi, K.; Ait Ben Haddou, E.; Benomar, A.; Abouqal, R.; Yahyaoui, M. Quality of life and multiple sclerosis: Arabic language translation and transcultural adaptation of “MSQOL-54”. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 168, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen As, A.A.; Alsharafi, J.A.; Aldaihan, M.M.; Alrushud, A.S.; Aldera, A.A.; Alder, M.A.; Alhammad, S.; Farrag, A.; Elsayed, W.; Almurdi, M.; et al. Validation of the Arabic Version of Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-29 (MSCOL-29-Ar): Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Analysis. NeuroRehabilitation 2025, 57, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solari, A.; Filippini, G.; Mendozzi, L.; Ghezzi, A.; Cifani, S.; Barbieri, E.; Baldini, S.; Salmaggi, A.; Mantia, L.L.; Farinotti, M.; et al. Validation of Italian multiple sclerosis quality of life 54 questionnaire. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 67, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquadro, C.; Lafortune, L.; Mear, I. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Translation in French Canadian of the MSQoL-54. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idiman, E.; Uzunel, F.; Ozakbas, S.; Yozbatiran, N.; Oguz, M.; Callioglu, B.; Gokce, N.; Bahar, Z. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of multiple sclerosis quality of life questionnaire (MSQOL-54) in a Turkish multiple sclerosis sample. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 240, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaem, H.; Borhani Haghighi, A.; Jafari, P.; Nikseresht, A.R. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the multiple sclerosis quality of life questionnaire. Neurol. India 2007, 55, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, M.; Banitaba, S.M.; Azizi, S. Validation of Persian Multiple Sclerosis quality of life-29 (P-MSQOL-29) questionnaire. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2023, 123, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füvesi, J.; Bencsik, K.; Benedek, K.; Mátyás, K.; Mészáros, E.; Rajda, C.; Losonczi, E.; Fricska-Nagy, Z.; Vécsei, L. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the ‘Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Instrument’ in Hungarian. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmezovic, T.; Kisic Tepavcevic, D.; Kostic, J.; Drulovic, J. Validation and cross-cultural adaptation of the disease-specific questionnaire MSQOL-54 in Serbian multiple sclerosis patients sample. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, M.; Guillamón, I.; Perkal, H.; Nos, C.; Porcel, J.; Berra, S.; Rajmil, L.; Montalbán, X. Spanish adaptation of the disease-specific questionnaire MSQOL-54 in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurologia 2006, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Estiasari, R.; Melani, S.; Kusumawardhani, A.A.A.A.; Pangeran, D.; Fajrina, Y.; Maharani, K.; Imran, D. Validation of the Indonesian version of multiple sclerosis quality of life-54 (MSQOL-54 INA) questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catic, T.; Culig, J.; Suljic, E.; Masic, A.; Gojak, R. Validation of the Disease-specific Questionnaire MSQoL-54 in Bosnia and Herzegovina Multiple Sclerosis Patients Sample. Med. Arch. 2017, 71, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.K.; Basso, M.R.; Candilis, P.J.; Combs, D.R.; Woods, S.P. Pain is associated with prospective memory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2014, 36, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Graff, L.A.; Patten, S.B.; Bolton, J.M.; Fisk, J.D.; Hitchon, C.; Marriott, J.J.; Marrie, R.A. CIHR Team in Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Immune-mediated Inflammatory Disease. Pain and participation in social activities in people with relapsing remitting and progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J.–Exp. Transl. Clin. 2023, 9, 20552173231188469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.L.; Ware, J.E. (Eds.) Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Albishi, A.M.; Alruwaili, M.B.; Alsubiheen, A.M.; Alnahdi, A.H.; Alokaily, A.O.; Algabbani, M.F.; Alrahed Alhumaid, L.A.; Alderaa, A.A.; Aljarallah, S. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Arabic version of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albishi, A.M.; Althubaiti, M.; Alharbi, N.; Almutairi, F. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the assessment life habits (LIFE-H 3.1) scale for patients with stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 6483–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educ. Med. J. 2019, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.L.; Raichle, K.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Ehde, D.M.; Kraft, G. The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with multiple sclerosis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2006, 32, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkawi, A.S.; Tsang, S.; Abolkhair, A.; Alsharif, M.; Alswiti, M.; Alsadoun, A.; AlZoraigi, U.S.; Aldhahri, S.F.; Al-Zhahrani, T.; Altirkawi, K.A. Development and validation of Arabic version of the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11, S2–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. A diagnostic meta-analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) algorithm scoring method as a screen for depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, H.; Atoui, M.; Hamadeh, A.; Zeinoun, P.; Nahas, Z. Adaptation and initial validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire—9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 239, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHadi, A.N.; AlAteeq, D.A.; Al-Sharif, E.; Bawazeer, H.M.; Alanazi, H.; AlShomrani, A.T.; Shuqdar, R.M.; AlOwaybil, R. An arabic translation, reliability, and validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summaka, M.; Zein, H.; Abbas, L.A.; Elias, C.; Elias, E.; Fares, Y.; Naim, I.; Nasser, Z. Validity and Reliability of the Arabic Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury in Lebanon. World Neurosurg. 2019, 125, e1016–e1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawami, A.S.; Abdulla, F.A. Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the modified fatigue impact scale in patients with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 3251–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, J.; Lamping, D.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Riazi, A.; Thompson, A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): A new patient-based outcome measure. Brain A J. Neurol. 2001, 124, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamper, S.J.; Maher, C.G.; Mackay, G. Global rating of change scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2009, 17, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albishi, A.M.; Altowairqi, R.T.; Alhadlaq, S.A.; Alsulboud, S.K.; Alhusaini, A.A.; Alokaily, A.O.; Alotibi, M. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validation of the Arabic version of the Motor Activity Log (MAL-30) Scale in patients with stroke in Saudi Arabia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 7042–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L.; Ostelo, R.W.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: A scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.L.; Turner, A.P.; Williams, R.M.; Bowen, J.D.; Hatzakis, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Haselkorn, J.K. Correlates of pain interference in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2006, 51, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasap, Z.; Uğurlu, H. Pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 69, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.L.; Jensen, M.P.; Ehde, D.M.; Hanley, M.A.; Kraft, G. Psychosocial factors associated with pain intensity, pain-related interference, and psychological functioning in persons with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain 2007, 127, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B.; Curran, P.J. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, P. Measurement of health outcomes in the clinical setting: Applications to physiotherapy. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2001, 17, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, D.; Manella, C.; Bender, A.; Ruger, L.; Long, M. Massage therapy may help manage fatigue, pain, and spasticity in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, R. Fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis: Diagnosis, impact and management. Mult. Scler. 2003, 9, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkelbach, S.; Sittinger, H.; Koenig, J. Is there a differential impact of fatigue and physical disability on quality of life in multiple sclerosis? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupp, L.B. Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management; Demos Medical Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, A.; Magalhaes, S.; Richard, J.F.; Audet, B.; Moore, C. The link between multiple sclerosis and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, K.B.; Jensen, T.S.; Hansen, H.J.; Bach, F.W. Sensory function and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain 2005, 114, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean ± SD or Count (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 121) | Retest (n = 50) | ||

| Age (Years) | 37.60 ± 7.759 | 38.8 ± 6.9 | |

| Sex | Male | 49 (40.5%) | 20 (40%) |

| Female | 72 (59.5%) | 30 (60%) | |

| Disease Duration (Years) | 13.08 ± 5.346 | 13.2 ± 5.8 | |

| Disease Type | RR | 105 (86.78%) | 42 (84%) |

| SP | 16 (13.22%) | 8 (16%) | |

| Diagnose with Depression: | Yes | 33 (27.3%) | 11 (22%) |

| No | 88 (72%) | 39 (78%) | |

| Scale/Item | Floor (n) | Floor (%) | Ceiling (n) | Ceiling (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PES-Ar Score | 15 | 12.4 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Mood | 26 | 21.5 | 4 | 3.3 |

| Ability To Walk or Move Around | 50 | 41.3 | 11 | 9.1 |

| Sleep | 46 | 38.0 | 12 | 9.9 |

| Normal Work | 48 | 39.7 | 5 | 4.1 |

| Recreational Activities | 47 | 38.8 | 10 | 8.3 |

| Enjoyment of Life | 45 | 37.2 | 11 | 9.1 |

| Items | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|

| Mood | 0.591 | 0.914 |

| Ability to walk or move around | 0.575 | 0.905 |

| Sleep | 0.755 | 0.893 |

| Normal work | 0.828 | 0.883 |

| Recreational activities | 0.840 | 0.881 |

| Enjoyment of life | 0.820 | 0.883 |

| Mean ± SD | ICC (2,1) (95%CI) | SEM | MDC95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PES-AR-Test | 14.07 ± 5.45 | 0.88 (0.85, 0.92) | 2.00 | 5.54 |

| PES-Ar-Retest | 14.85 ± 6.13 |

| Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Mood | 0.693 |

| Ability to walk or move around | 0.771 |

| Sleep | 0.837 |

| Normal work | 0.891 |

| Recreational activities | 0.899 |

| Enjoyment of life | 0.887 |

| Variable | Spearman’s r with PES | p-Value | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | 0.677 | <0.001 | [0.57, 0.77] |

| SF-MPQ | 0.586 | <0.001 | [0.46, 0.69] |

| MFIS | 0.660 | <0.001 | [0.55, 0.75] |

| MSIS-29 (Psychological) | 0.085 | 0.354 | [−0.09, 0.26] |

| MSIS-29 (Physical) | 0.188 | 0.039 | [0.01, 0.36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Albishi, A.M.; Alshammari, Z.S.; Almhawas, S.S.; Alimam, D.M.; Alosaimi, M.H.; Aljarallah, S. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the MOS Pain Effect Scale in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare 2026, 14, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14030285

Albishi AM, Alshammari ZS, Almhawas SS, Alimam DM, Alosaimi MH, Aljarallah S. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the MOS Pain Effect Scale in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare. 2026; 14(3):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14030285

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbishi, Alaa M., Zainab S. Alshammari, Sarah S. Almhawas, Dalia M. Alimam, Manal H. Alosaimi, and Salman Aljarallah. 2026. "Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the MOS Pain Effect Scale in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis" Healthcare 14, no. 3: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14030285

APA StyleAlbishi, A. M., Alshammari, Z. S., Almhawas, S. S., Alimam, D. M., Alosaimi, M. H., & Aljarallah, S. (2026). Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the MOS Pain Effect Scale in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare, 14(3), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14030285