Intention to Use Digital Health Among COPD Patients in Europe: A Cluster Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Population

2.2. Study Tools

2.3. Outcome Measurement

2.4. Predictors

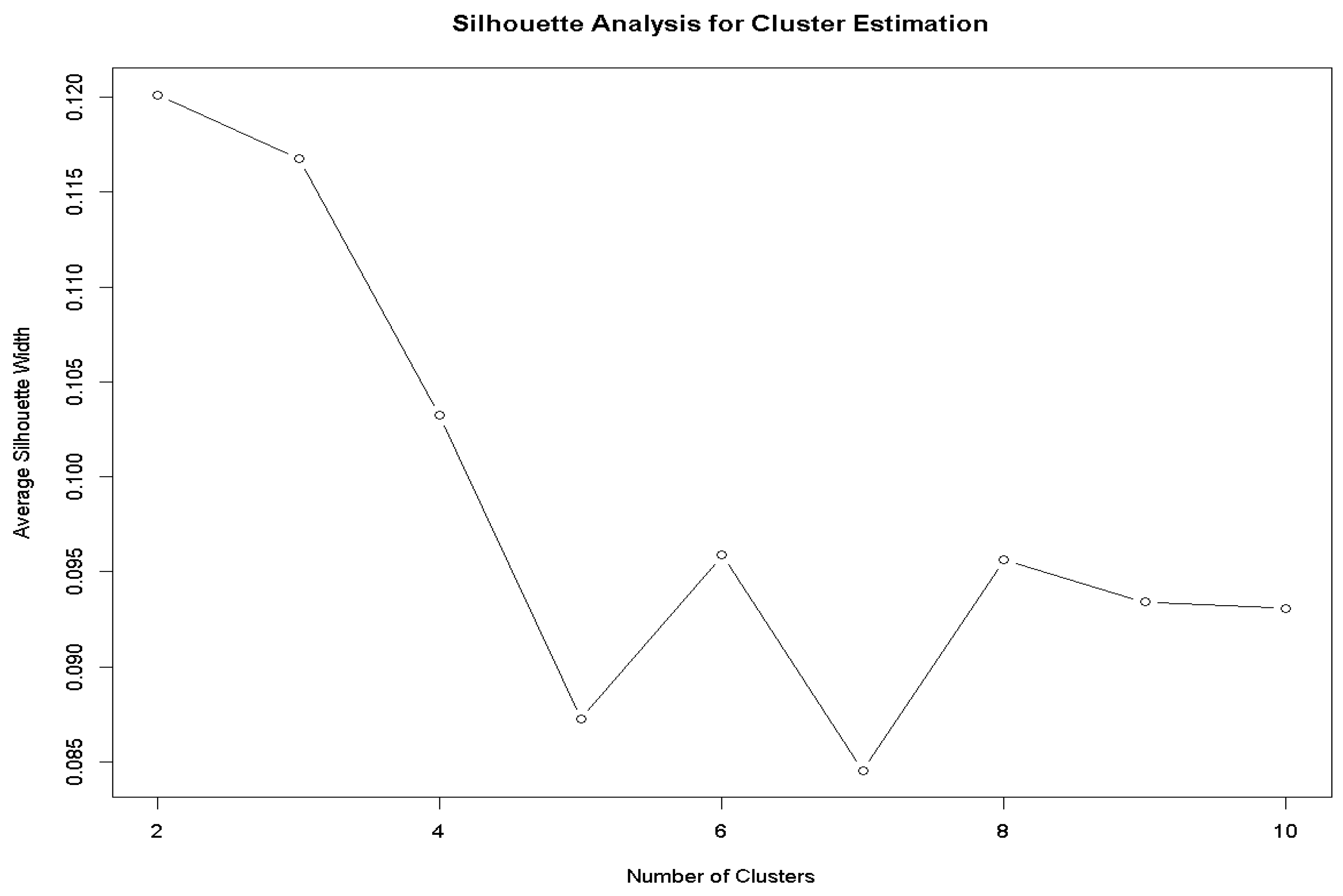

2.5. Data Analysis for Cluster Development

2.6. Inferential Analysis

2.7. Cluster Analysis

2.8. Sample Size Determination

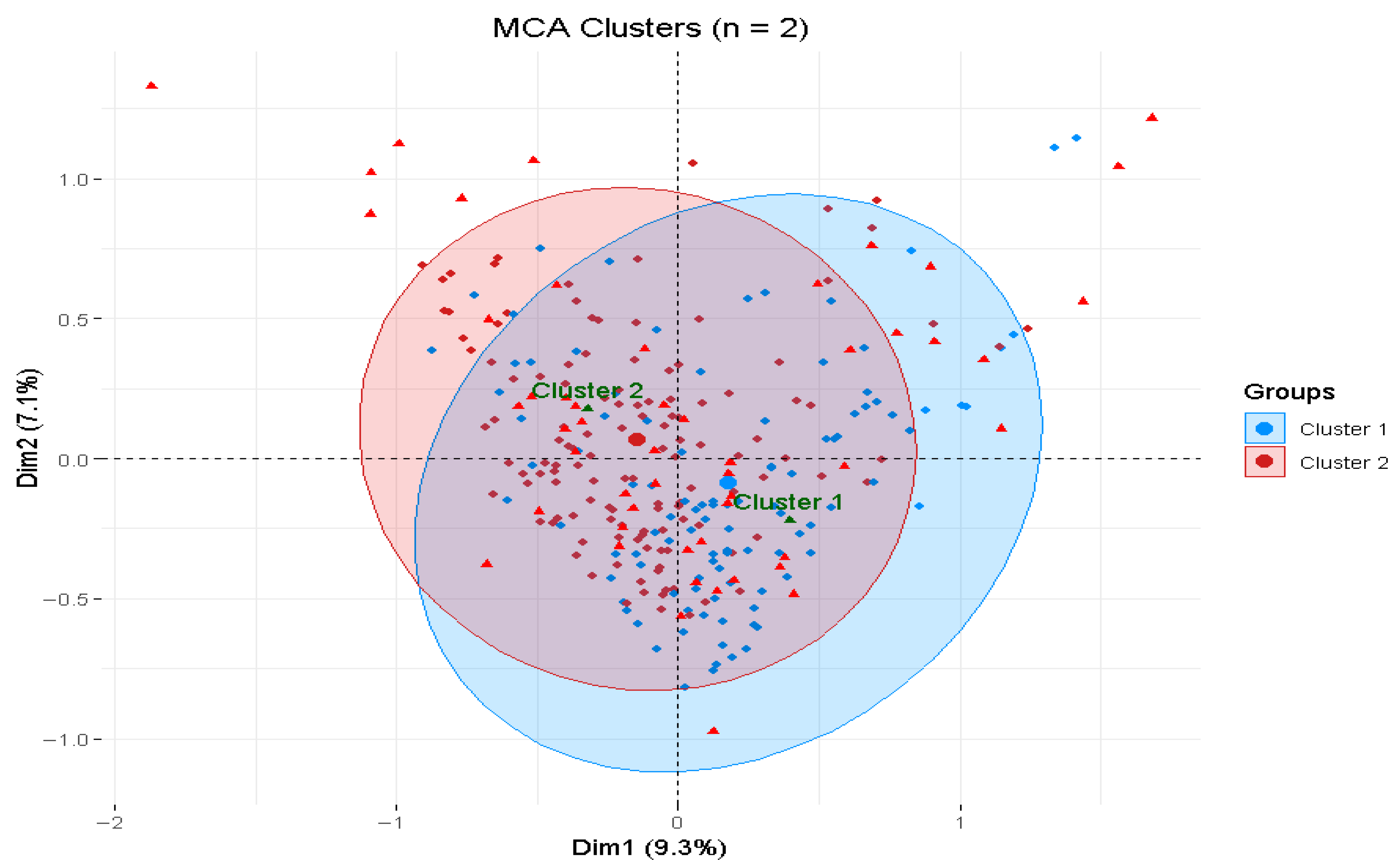

2.9. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

2.10. Outcome Measurements and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Character

Cluster Differences in Sociodemographic and UTAUT Predictors

3.2. Cross-Country Differences in Intention to Use Digital Health: Consideration of UTAUT Constructs and Sociodemographic Factors

3.3. User Intention to Use Digital Health Across Clusters

3.4. Cluster Profiles of Digital Health Intention and UTAUT Predictors

3.4.1. Balanced-Hesitant Subgroup

3.4.2. Positive Intention Subgroup

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Study

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| GRIAC | Groningen Research Institute for Asthma and COPD |

| DHI | Digital Health Intervention |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| PAM | Partitioning Around Medoids |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| METc | Medical Ethics Committee |

| UMCG | University Medical Center Groningen |

| ARI | Adjusted Rand Index |

| CH Index | Calinski–Harabasz Index |

References

- Demographic Change in Europe—October 2023—Eurobarometer Survey. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3112 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Gianfredi, V.; Nucci, D.; Pennisi, F.; Maggi, S.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P. Aging, longevity, and healthy aging: The public health approach. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.K.; Raja, A.; Brown, B.D. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559281/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Marshall, D.C.; Al Omari, O.; Goodall, R.; Shalhoub, J.; Adcock, I.M.; Chung, K.F.; Salciccioli, J.D. Trends in prevalence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life-years relating to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Europe: An observational study of the global burden of disease database, 2001–2019. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmeier, S.G.; Hartmann, A.P. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A review focusing on exacerbations. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, S.; Bora, K.S. Capitalization of digital healthcare: The cornerstone of emerging medical practices. Intell. Pharm. 2025, 3, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeamii, V.C.; Okobi, O.E.; Wambai-Sani, H.; Perera, G.S.; Zaynieva, S.; Okonkwo, C.C.; Ohaiba, M.M.; William-Enemali, P.C.; Obodo, O.R.; Obiefuna, N.G. Revolutionizing Healthcare: How Telemedicine Is Improving Patient Outcomes and Expanding Access to Care. Cureus 2024, 16, e63881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Stuckler, D.; McNamara, C.L. Digital Interventions to reduce hospitalization and hospital readmission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patient: Systematic review. BMC Digit. Health 2024, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achelrod, D.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Health-economic evaluation of home telemonitoring for COPD in Germany: Evidence from a large population-based cohort. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, E.; Richter, P.; Schlieter, H. All Together Now—Patient Engagement, Patient Empowerment, and Associated Terms in Personal Healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erku, D.; Khatri, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Digital Health Interventions to Improve Access to and Quality of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, E.-J.; Park, S.; Lee, M. Digital Health Intervention Effect on Older Adults with Chronic Diseases Living Alone: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TheGlobalEconomy.com [Internet]. Mobile Network Coverage in Europe. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/Mobile_network_coverage/Europe/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Digital Health and Care—Public Health—European Commission. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/digital-health-and-care_en (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Admassu, W.; Gorems, K. Analyzing health service employees’ intention to use e-health systems in southwest Ethiopia: Using UTAUT-2 model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bente, B.E.; Van Dongen, A.; Verdaasdonk, R.; van Gemert-Pijnen, L. eHealth implementation in Europe: A scoping review on legal, ethical, financial, and technological aspects. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1332707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Veer, A.J.E.; Peeters, J.M.; Brabers, A.E.; Schellevis, F.G.; Rademakers, J.J.J.; Francke, A.L. Determinants of the intention to use e-Health by community dwelling older people. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppini, V.; Ferraris, G.; Ferrari, M.V.; Dahò, M.; Kirac, I.; Renko, I.; Monzani, D.; Grasso, R.; Pravettoni, G. Patients’ perspectives on cancer care disparities in Central and Eastern European countries: Experiencing taboos, misinformation and barriers in the healthcare system. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1420178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Equity Status Report Initiative. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/initiatives/health-equity-status-report-initiative (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Bucciardini, R.; Zetterquist, P.; Rotko, T.; Putatti, V.; Mattioli, B.; De Castro, P.; Napolitani, F.; Giammarioli, A.M.; Kumar, B.N.; Nordström, C.; et al. Addressing health inequalities in Europe: Key messages from the Joint Action Health Equity Europe (JAHEE). Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Health Data Space (EHDS). Available online: https://www.european-health-data-space.com/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Mamuye, A.; Nigatu, A.M.; Chanyalew, M.A.; Amor, L.B.; Loukil, S.; Moyo, C.; Quarshie, S.; Antypas, K.; Tilahun, B. Facilitators and Barriers to the Sustainability of eHealth Solutions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Descriptive Exploratory Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e41487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, N.; Lokker, C.; Ghasemaghaei, M.; DiLiberto, D. eHealth Implementation Issues in Low-Resource Countries: Model, Survey, and Analysis of User Experience. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, K.; Jaramillo, C.; Barteit, S. Telemedicine in Low- and Middle-Income Countries During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 914423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, A.; Hickie, I.B.; Alam, M.; Wilson, C.E.; LaMonica, H.M. Access to Mobile Health in Lower Middle-Income Countries: A Review. Health Technol. 2025, 15, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazzi, A.; Quaglia, V.; Bongelli, R. Barriers and facilitators to health technology adoption by older adults with chronic diseases: An integrative systematic review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metting, E.; van Luenen, S.; Baron, A.-J.; Tran, A.; van Duinhoven, S.; Chavannes, N.H.; Hevink, M.; Lüers, J.; Kocks, J. Overcoming the Digital Divide for Older Patients with Respiratory Disease: Focus Group Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e44028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, L.M.; Krukowski, R.A.; Kuntsche, E.; Busse, H.; Gumbert, L.; Gemesi, K.; Neter, E.; Mohamed, N.F.; Ross, K.M.; John-Akinola, Y.O.; et al. Reducing intervention- and research-induced inequalities to tackle the digital divide in health promotion. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.J. Improving health literacy using the power of digital communications to achieve better health outcomes for patients and practitioners. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1264780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Rashid, A.M.; Ouyang, S. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241229570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Jeyaraj, A.; Clement, M.; Williams, M.D. Re-examining the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): Towards a Revised Theoretical Model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, H.; Dai, C.; Yuan, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, F.; Liang, Z. Quantitative CT and COPD: Cluster analysis reveals five distinct subtypes with varying exacerbation risks. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yu, F.; Cao, Z.; Huang, K.; Chen, Q.; Geldsetzer, P.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Bärnighausen, T.; Yang, T.; et al. Exploring COPD Patient Clusters and Associations with Health-Related Quality of Life Using a Machine Learning Approach: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Engineering 2025, 50, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhanie, Y.A.; Bailly, S.; Amroussa, I.; Veale, D.; Hérengt, F.; Verges, S. Clustering of COPD patients and their response to pulmonary rehabilitation. Respir. Med. 2022, 198, 106861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.; van Dijk, J.A. The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittas, V.; Zecca, C.; Kamm, C.P.; Kuhle, J.; Chan, A.; von Wyl, V. Digital health for chronic disease management: An exploratory method to investigating technology adoption potential. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaglia, J.; Jaghab, B.; Ismail, M.; Hänsel, K.; Meter, A.V.; Kirschenbaum, M.; Sobolev, M.; Kane, J.M.; Tang, S.X. Assessing Health Technology Literacy and Attitudes of Patients in an Urban Outpatient Psychiatry Clinic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2024, 11, e63034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violán, C.; Roso-Llorach, A.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Guisado-Clavero, M.; Pons-Vigués, M.; Pujol-Ribera, E.; Valderas, J.M. Multimorbidity patterns with K-means nonhierarchical cluster analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.H.; Hermansen, Å.; Dahl, K.G.; Lønning, K.; Meyer, K.B.; Vidnes, T.K.; Wahl, A.K. Profiles of health literacy and digital health literacy in clusters of hospitalised patients: A single-centre, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metting, E.I. Cultural differences in technology acceptance of COPD patients oh cool: A crosscountry focusgroup study. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, PA2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamolhoda, M.; Ayatollahi, S.M.T.; Bagheri, Z. A comparative study of the impacts of unbalanced sample sizes on the four synthesized methods of meta-analytic structural equation modeling. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.D.; Car, J.; Pagliari, C.; Anandan, C.; Cresswell, K.; Bokun, T.; McKinstry, B.; Procter, R.; Majeed, A.; Sheikh, A. The Impact of eHealth on the Quality and Safety of Health Care: A Systematic Overview. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1000387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florensa, D.; Mateo-Fornés, J.; Solsona, F.; Pedrol Aige, T.; Mesas Julió, M.; Piñol, R.; Godoy, P. Use of Multiple Correspondence Analysis and K-means to Explore Associations Between Risk Factors and Likelihood of Colorectal Cancer: Cross-sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e29056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.Y.; Moxley, J.; Sharit, J.; Czaja, S.J. Beyond the Digital Divide: Factors Associated with Adoption of Technologies Related to Aging in Place. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2025, 44, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.-C.; De Santis, K.K.; Muellmann, S.; Hoffmann, S.; Spallek, J.; Barnils, N.P.; Ahrens, W.; Zeeb, H.; Schüz, B. Sociodemographics and Digital Health Literacy in Using Wearables for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: Cross-Sectional Nationwide Survey in Germany. J. Prev. 2025, 46, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, Q.; Guo, H.; Duan, X.; Xu, X.; Yue, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S. Determinants of digital health literacy among older adult patients with chronic diseases: A qualitative study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1568043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams-Ghahfarokhi, Z. Challenges in health and technological literacy of older adults: A qualitative study in Isfahan. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.M.T.; Wong, R.S.H.; Goh, W.J.W.H.; Hilal, S. Facilitators and Barriers for Use of Digital Technology in Chronic Disease Management. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanahara, N.; Hirabayashi, M.; Mamada, T.; Nishimoto, M.; Iyo, M. Combination therapy of electroconvulsive therapy and aripiprazole for dopamine supersensitivity psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 202, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, J.; Williams, L.; McCann, L. Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Technology Adoption Among Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: Updated Systematic Review. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e80000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuitert, I.; Marinus, J.D.; Dalenberg, J.R.; van ’t Veer, J.T. Digital Health Technology Use Across Socioeconomic Groups Prior to and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Panel Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e55384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, B.; Sun, J.; Zeng, X. Determinants of Chronic Disease Patients’ Intention to Use Internet Diagnosis and Treatment Services: Based on the UTAUT2 Model. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1543428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turja, T.; Jylhä, V.; Rosenlund, M.; Kuusisto, H. Beyond early and late adopters: Reimagining health technology readiness through health-related circumstances. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, Y.; Agarwal, P.; Chintamani, A.A.; Pahurkar, R.; Bhinde, H.N.; Sharma, V. Perceived Ease of Use and Health Literacy as Determinants of mHealth App Usage Among Older Adults in India: A SEM Approach. Discov. Soc. Sci. Health 2025, 5, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ji, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, K.; Jiang, X.; Chang, C. Study on the “digital divide” in the continuous utilization of Internet medical services for older adults: Combination with PLS-SEM and fsQCA analysis approach. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokisch, M.R.; Schmidt, L.I.; Doh, M. Acceptance of digital health services among older adults: Findings on perceived usefulness, self-efficacy, privacy concerns, ICT knowledge, and support seeking. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1073756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, A.; Díaz-Martín, A.M.; Yagüe Guillén, M.J. Modifying UTAUT2 for a cross-country comparison of telemedicine adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Van den Broucke, S.; Bíró, É.; Bøggild, H.; Bruton, L.; De Gani, S.M.; Finbråten, H.S.; Gibney, S.; Griebler, R.; Griese, L.; et al. Measuring Digital Health Literacy and Its Associations with Determinants and Health Outcomes in 13 Countries. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Sykes, T.A.; Zhang, X. ICT for Development in Rural India: A Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health Outcomes. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qoseem, I.O.; Okesanya, O.J.; Olaleke, N.O.; Ukoaka, B.M.; Amisu, B.O.; Ogaya, J.B.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., III. Digital health and health equity: How digital health can address healthcare disparities and improve access to quality care in Africa. Health Promot. Perspect. 2024, 14, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Cluster 1 (n = 104) | Cluster 2 (n = 128) | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 43 (41.4%) | 47 (36.7%) | 90 (38.79%) | 0.472 |

| Female | 61 (58.7%) | 81 (63.3%) | 142 (61.21%) | ||

| Age Group | 29–55 | 12 (11.5%) | 28 (21.9%) | 40 (17.24%) | 0.082 |

| 55–64 | 22 (21.2%) | 34 (26.6%) | 56 (24.14%) | ||

| 65–79 | 60 (57.7%) | 57 (44.5%) | 117 (50.43%) | ||

| 80+ | 10 (9.6%) | 9 (7.0%) | 19 (8.19%) | ||

| Work Status | Employed | 23 (22.1%) | 32 (25.0%) | 55 (23.71%) | 0.854 |

| Unemployed | 1 (1.0%) | 3 (2.3%) | 4 (1.72%) | ||

| Medically unfit | 16 (15.4%) | 18 (14.1%) | 34 (14.66%) | ||

| Retired | 59 (56.7%) | 71 (55.5%) | 130 (56.03%) | ||

| Other | 5 (4.8%) | 4 (3.1%) | 9 (3.88%) | ||

| Education | Low | 68 (65.4%) | 34 (26.6%) | 102 (43.97%) | <0.001 *** |

| Middle | 14 (13.5%) | 16 (12.5%) | 30 (12.93%) | ||

| High | 22 (21.2%) | 78 (60.9%) | 100 (43.10%) | ||

| Computer Use at Work | None | 27 (26.0%) | 74 (57.8%) | 101 (43.53%) | <0.001 *** |

| Occasional | 33 (31.7%) | 37 (28.9%) | 70 (30.17%) | ||

| Frequent | 44 (42.3%) | 17 (13.3%) | 61 (26.29%) | ||

| Living Situation | Lives alone | 27 (26.0%) | 47 (36.7%) | 74 (31.90%) | 0.08 |

| Doesn’t live alone | 77 (74.0%) | 81 (63.3%) | 158 (68.10%) | ||

| Country | Netherlands | 26 (25.0%) | 34 (26.6%) | 25 (10.78%) | 0.315 |

| Flanders | 21 (20.2%) | 25 (19.5%) | 46 (19.83%) | ||

| Germany | 16 (15.4%) | 12 (9.4%) | 28 (12.07%) | ||

| Romania | 14 (13.5%) | 21 (16.4%) | 60 (25.86%) | ||

| UK | 20 (19.2%) | 18 (14.1%) | 35 (15.09%) | ||

| Other | 7 (6.7%) | 18 (14.1%) | 38 (16.38%) | ||

| Health Conditions | COPD | 68 (65.4%) | 74 (57.8%) | 142 (61.21%) | 0.748 |

| Asthma | 9 (8.7%) | 11 (8.6%) | 20 (8.62%) | ||

| Asthma/COPD overlap | 16 (15.4%) | 28 (21.9%) | 44 (18.97%) | ||

| Cystic Fibrosis | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (0.86%) | ||

| Other | 10 (9.6%) | 14 (10.9%) | 24 (10.34%) | ||

| Physical Problems | Yes | 69 (66.4%) | 97 (75.8%) | 166 (71.55%) | 0.113 |

| No | 35 (33.7%) | 31 (24.2%) | 66 (28.45%) | ||

| Digital health Experience | Negative | 8 (7.7%) | 10 (7.8%) | 18 (7.76%) | <0.001 *** |

| Neutral | 78 (75.0%) | 42 (32.8%) | 120 (51.72%) | ||

| Positive | 18 (17.3%) | 76 (59.4%) | 94 (40.51%) | ||

| Social Influence | Negative | 16 (15.4%) | 44 (34.4%) | 120 (51.72%) | <0.001 *** |

| Neutral | 65 (62.5%) | 35 (27.3%) | 94 (40.52%) | ||

| Positive | 23 (22.1%) | 49 (38.3%) | 60 (25.86%) | ||

| Effort Expectancy | Negative | 30 (28.9%) | 17 (13.3%) | 100 (43.10%) | <0.001 *** |

| Neutral | 58 (55.8%) | 19 (14.8%) | 72 (31.03%) | ||

| Positive | 16 (15.4%) | 92 (71.9%) | 36 (15.52%) | ||

| Performance Expectancy | Negative | 28 (26.9%) | 50 (39.1%) | 49 (21.12%) | 0.041 * |

| Neutral | 68 (65.4%) | 75 (58.6%) | 147 (63.36%) | ||

| Positive | 8 (7.7%) | 3 (2.3%) | 47 (20.26%) | ||

| Digital Literacy | Basic or above | 86 (82.7%) | 121 (94.5%) | 207 (89.22%) | 0.004 ** |

| No basic literacy | 18 (17.3%) | 7 (5.5%) | 25 (10.77%) | ||

| Voluntariness | Negative | 56 (53.9%) | 29 (22.7%) | 85 (36.63%) | <0.001 *** |

| Neutral | 10 (9.6%) | 15 (11.7%) | 25 (10.77%) | ||

| Positive | 38 (36.5%) | 84 (65.6%) | 122 (52.58%) |

| Countries | Negative (%) | Neutral (%) | Positive (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 10 (27.78) | 16 (32.65) | 34 (23.13) | 60 (25.86) |

| Flanders | 3 (8.33) | 10 (20.41) | 33 (22.45) | 46 (19.83) |

| Romania | 3 (8.33) | 5 (10.20) | 27 (18.37) | 35 (15.09) |

| Germany | 3 (8.33) | 8 (16.33) | 17 (11.56) | 28 (12.07) |

| UK | 13 (36.11) | 9 (18.37) | 16 (10.88) | 38 (16.38) |

| Others | 4 (11.11) | 1 (2.04) | 20 (13.61) | 25 (10.78) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alem, S.G.; Nguyen, L.; Hipólito, N.; Spiller, M.; Metting, E. Intention to Use Digital Health Among COPD Patients in Europe: A Cluster Analysis. Healthcare 2026, 14, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020178

Alem SG, Nguyen L, Hipólito N, Spiller M, Metting E. Intention to Use Digital Health Among COPD Patients in Europe: A Cluster Analysis. Healthcare. 2026; 14(2):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020178

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlem, Solomon Getachew, Le Nguyen, Nadia Hipólito, Maelle Spiller, and Esther Metting. 2026. "Intention to Use Digital Health Among COPD Patients in Europe: A Cluster Analysis" Healthcare 14, no. 2: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020178

APA StyleAlem, S. G., Nguyen, L., Hipólito, N., Spiller, M., & Metting, E. (2026). Intention to Use Digital Health Among COPD Patients in Europe: A Cluster Analysis. Healthcare, 14(2), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020178