Nutritional Support via Jejunostomy Placed During Staging Laparoscopy for Esophagogastric Cancer: A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Nutritional and Clinical Data

3. Results

3.1. Patients Characteristics: Demographics, Cancer Diagnosis, Comorbidities

3.2. Cancer Treatments

3.3. Nutritional Assessment

3.3.1. T0—First Nutritional Assessment After Diagnosis

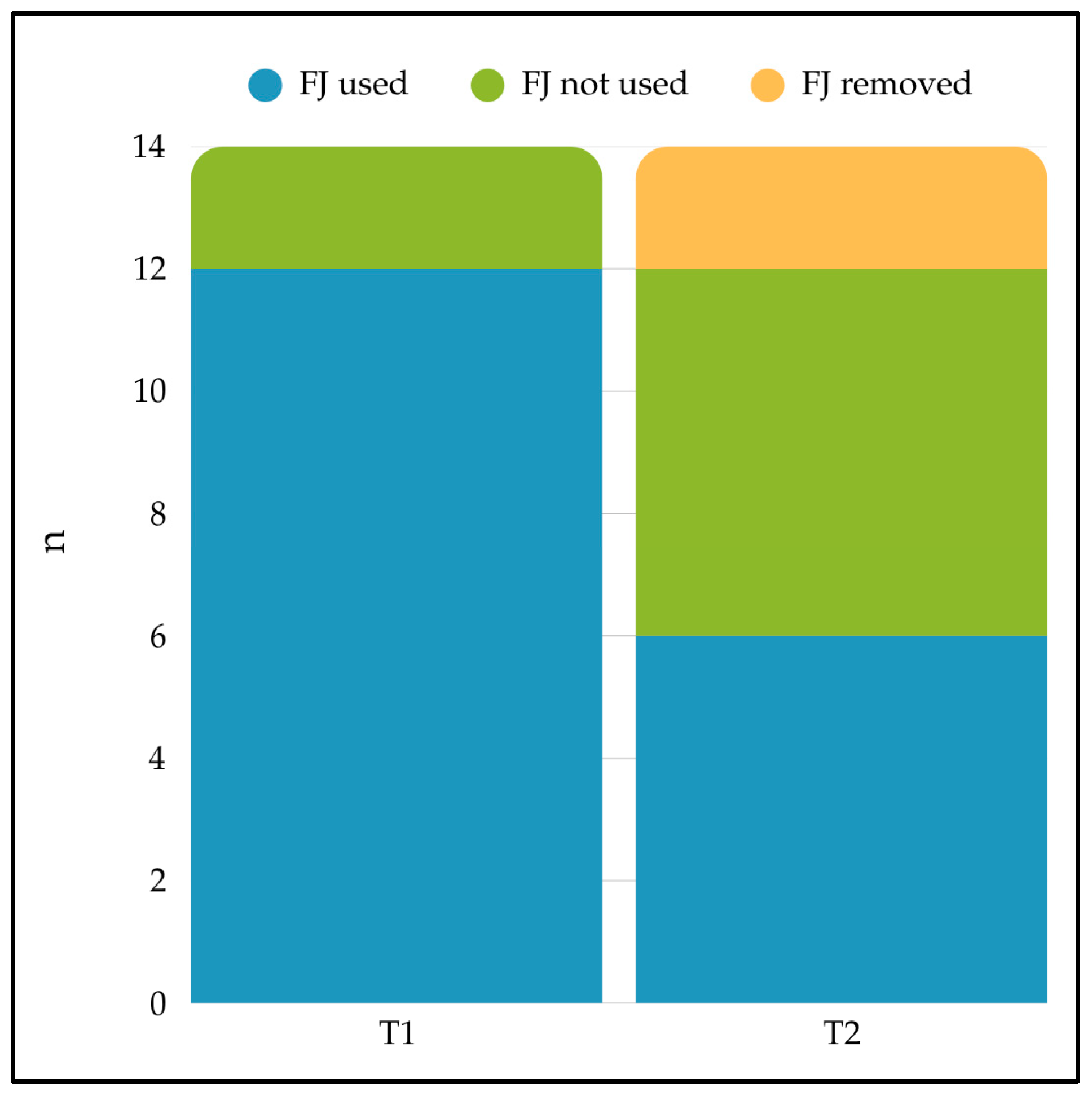

3.3.2. T1—Nutritional Assessment After FJ Placement

3.3.3. T2—Nutritional Evaluation at Restaging

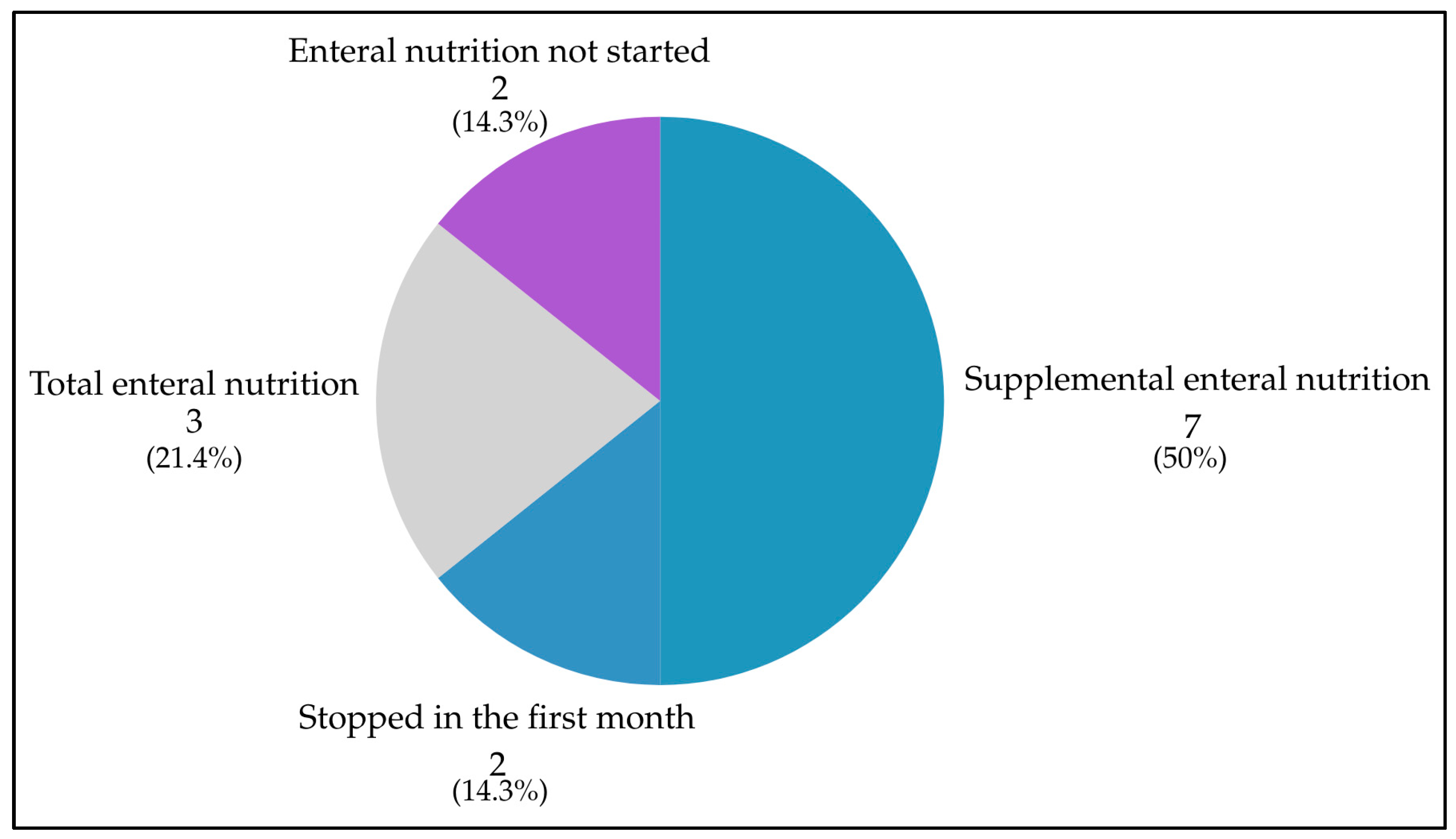

3.4. Feeding Jejunostomy Use

3.5. Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGCs | Esophagogastric cancers |

| FJ | Feeding Jejunostomy |

| SL | Staging Laparoscopy |

| T0 | First nutritional assessment after diagnosis |

| T1 | Nutritional assessment after FJ placement |

| T2 | Nutritional evaluation at restaging |

| WLGS | Weight Loss Grading system |

| NRS-2002 | 2002 Nutritional Risk Screening |

| MUST | Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool |

| BEE | Basal Energy Expenditure |

| TDEE | Total Daily Energy Expenditure |

| ONS | Oral Nutritional Supplements |

| HEN | Home enteral nutrition |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Otake, R.; Kozuki, R.; Toihata, T.; Takahashi, K.; Okamura, A.; Imamura, Y. Recent Progress in Multidisciplinary Treatment for Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Surg. Today 2020, 50, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilson, D.H.; Van Hillegersberg, R. Management of Patients with Adenocarcinoma or Squamous Cancer of the Esophagus. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.C.; Nilsson, M.; Grabsch, H.I.; Van Grieken, N.C.; Lordick, F. Gastric Cancer. Lancet 2020, 396, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordick, F.; Carneiro, F.; Cascinu, S.; Fleitas, T.; Haustermans, K.; Piessen, G.; Vogel, A.; Smyth, E.C. Gastric Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, D.; Allum, W.H.; Stenning, S.P.; Thompson, J.N.; Van De Velde, C.J.H.; Nicolson, M.; Scarffe, J.H.; Lofts, F.J.; Falk, S.J.; Iveson, T.J.; et al. Perioperative Chemotherapy versus Surgery Alone for Resectable Gastroesophageal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ychou, M.; Boige, V.; Pignon, J.-P.; Conroy, T.; Bouché, O.; Lebreton, G.; Ducourtieux, M.; Bedenne, L.; Fabre, J.-M.; Saint-Aubert, B.; et al. Perioperative Chemotherapy Compared with Surgery Alone for Resectable Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma: An FNCLCC and FFCD Multicenter Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hagen, P.; Hulshof, M.C.C.M.; Van Lanschot, J.J.B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Henegouwen, M.I.V.B.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; Richel, D.J.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; Hospers, G.A.P.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; et al. Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy for Esophageal or Junctional Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, D.; Cunningham, D.; Nankivell, M.; Blazeby, J.M.; Griffin, S.M.; Crellin, A.; Grabsch, H.I.; Langer, R.; Pritchard, S.; Okines, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Cisplatin and Fluorouracil versus Epirubicin, Cisplatin, and Capecitabine Followed by Resection in Patients with Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma (UK MRC OE05): An Open-Label, Randomised Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Batran, S.-E.; Homann, N.; Pauligk, C.; Goetze, T.O.; Meiler, J.; Kasper, S.; Kopp, H.-G.; Mayer, F.; Haag, G.M.; Luley, K.; et al. Perioperative Chemotherapy with Fluorouracil plus Leucovorin, Oxaliplatin, and Docetaxel versus Fluorouracil or Capecitabine plus Cisplatin and Epirubicin for Locally Advanced, Resectable Gastric or Gastro-Oesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A Randomised, Phase 2/3 Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjigian, Y.Y.; Al-Batran, S.-E.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Muro, K.; Molena, D.; Van Cutsem, E.; Hyung, W.J.; Wyrwicz, L.; Oh, D.-Y.; Omori, T.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab in Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E. Cancer-Associated Malnutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, X.-C.; Liu, D.-C.; Tong, C.; Wen, W.; Chen, R.-H. Clinical Significance of the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score in Gastric Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis of 9,764 Participants. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1156006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiflis, S.; Christodoulidis, G.; Papakonstantinou, M.; Giakoustidis, A.; Koukias, S.; Roussos, P.; Kouliou, M.N.; Koumarelas, K.E.; Giakoustidis, D. Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival of Patients with Gastric or Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma: A Systematic Review. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandavadivelan, P.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. The Weight Loss Grading System as a Predictor of Cancer Cachexia in Oesophageal Cancer Survivors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 1755–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandavadivelan, P.; Lagergren, P. Cachexia in Patients with Oesophageal Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, O.; Anandavadivelan, P.; Gossage, J.; Johar, A.M.; Lagergren, J.; Lagergren, P. The Impact of Pre- and Post-Operative Weight Loss and Body Mass Index on Prognosis in Patients with Oesophageal Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. EJSO 2017, 43, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deans, D.A.C.; Tan, B.H.; Wigmore, S.J.; Ross, J.A.; De Beaux, A.C.; Paterson-Brown, S.; Fearon, K.C.H. The Influence of Systemic Inflammation, Dietary Intake and Stage of Disease on Rate of Weight Loss in Patients with Gastro-Oesophageal Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo Lozano, E.; Osés Zárate, V.; Campos Del Portillo, R. Nutritional Management of Gastric Cancer. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2021, 68, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Ripley, R.T. Postgastrectomy Syndromes and Nutritional Considerations Following Gastric Surgery. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 97, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, A.; Carr, R.; Molena, D. Esophagectomy for Cancer in the Obese Patient. Ann. Esophagus 2020, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, R.L.G.M.; Lagarde, S.M.; Klinkenbijl, J.H.G.; Busch, O.R.C.; Van Berge Henegouwen, M.I. A High Body Mass Index in Esophageal Cancer Patients Does Not Influence Postoperative Outcome or Long-Term Survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Deng, G.; Shi, X.; Liu, Z.; Lin, A.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Body Mass Index, Weight Change, and Cancer Prognosis: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of 73 Cohort Studies. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition—A Consensus Report from the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aapro, M.; Arends, J.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Grunberg, S.M.; Herrstedt, J.; Hopkinson, J.; Jacquelin-Ravel, N.; Jatoi, A.; Kaasa, S.; et al. Early Recognition of Malnutrition and Cachexia in the Cancer Patient: A Position Paper of a European School of Oncology Task Force. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccialanza, R.; Cotogni, P.; Cereda, E.; Bossi, P.; Aprile, G.; Delrio, P.; Gnagnarella, P.; Mascheroni, A.; Monge, T.; Corradi, E.; et al. Nutritional Support in Cancer Patients: Update of the Italian Intersociety Working Group Practical Recommendations. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 2705–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, G.; Basile, D.; Giaretta, R.; Schiavo, G.; La Verde, N.; Corradi, E.; Monge, T.; Agustoni, F.; Stragliotto, S. The Clinical Value of Nutritional Care before and during Active Cancer Treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, G.; Corti, F.; Della Valle, S.; Di Bartolomeo, M. Nutritional Support Indications in Gastroesophageal Cancer Patients: From Perioperative to Palliative Systemic Therapy. A Comprehensive Review of the Last Decade. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, S.L.; Mahendran, H.A.; Wong, C.M.; Milaksh, N.K.; Nyunt, M. Laparoscopic T-Tube Feeding Jejunostomy as an Adjunct to Staging Laparoscopy for Upper Gastrointestinal Malignancies: The Technique and Review of Outcomes. BMC Surg. 2017, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredelli, S.; Delhorme, J.-B.; Venkatasamy, A.; Gaiddon, C.; Brigand, C.; Rohr, S.; Romain, B. Could a Feeding Jejunostomy Be Integrated into a Standardized Preoperative Management of Oeso-Gastric Junction Adenocarcinoma? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 3324–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.M.; Whiting, J.; Tan, B.H. Impact of Regular Enteral Feeding via Jejunostomy during Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Body Composition in Patients with Oesophageal Cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 11, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshier, P.R.; Klevebro, F.; Schmidt, A.; Han, S.; Jenq, W.; Puccetti, F.; Seesing, M.F.J.; Baracos, V.E.; Low, D.E. Impact of Early Jejunostomy Tube Feeding on Clinical Outcome and Parameters of Body Composition in Esophageal Cancer Patients Receiving Multimodal Therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 5689–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisinet, M.; Venkatasamy, A.; Alratrout, H.; Delhorme, J.-B.; Brigand, C.; Rohr, S.; Gaiddon, C.; Romain, B. How to Prevent Sarcopenia Occurrence during Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Oesogastric Adenocarcinoma? Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mathelin, P.; Manfredelli, S.; Delhorme, J.-B.; Venkatasamy, A.; Rohr, S.; Brigand, C.; Gaiddon, C.; Romain, B. Sarcopenia Remaining after Intensive Nutritional Feeding Support Could Be a Criterion for the Selection of Patients for Surgery for Oesogastric Junction Adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, T.K.; Lopez, A.N.; Sarosi, G.A.; Ben-David, K.; Thomas, R.M. Preoperative Enteral Access Is Not Necessary Prior to Multimodality Treatment of Esophageal Cancer. Surgery 2018, 163, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Shaikh, T.; Yee, J.-L.; Au, C.; Denlinger, C.S.; Handorf, E.; Meyer, J.E.; Dotan, E. Impact of Clinical Markers of Nutritional Status and Feeding Jejunostomy Use on Outcomes in Esophageal Cancer Patients Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroese, T.E.; Tapias, L.; Olive, J.K.; Trager, L.E.; Morse, C.R. Routine Intraoperative Jejunostomy Placement and Minimally Invasive Oesophagectomy: An Unnecessary Step? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 56, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koterazawa, Y.; Oshikiri, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Kanaji, S.; Yamashita, K.; Matsuda, T.; Nakamura, T.; Suzuki, S.; Kakeji, Y. Routine Placement of Feeding Jejunostomy Tube during Esophagectomy Increases Postoperative Complications and Does Not Improve Postoperative Malnutrition. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 33, doz021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sarrado, E.; Mingol Navarro, F.; Rosellón, J.R.; Ballester Pla, N.; Vaqué Urbaneja, F.J.; Muniesa Gallardo, C.; López Rubio, M.; García-Granero Ximénez, E. Feeding Jejunostomy after Esophagectomy Cannot Be Routinely Recommended. Analysis of Nutritional Benefits and Catheter-Related Complications. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 217, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.H.; Kooby, D.A.; Staley, C.A.; Maithel, S.K. An Assessment of Feeding Jejunostomy Tube Placement at the Time of Resection for Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 107, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.C.; Squires, M.H.; Postlewait, L.M.; Kooby, D.A.; Poultsides, G.A.; Weber, S.M.; Bloomston, M.; Fields, R.C.; Pawlik, T.M.; Votanopoulos, K.I.; et al. An Assessment of Feeding Jejunostomy Tube Placement at the Time of Resection for Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Seven-institution Analysis of 837 Patients from the U.S. Gastric Cancer Collaborative. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 112, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri, A.; Salehi, O.A.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Hosseini, S.; Shojaifard, A.; Khorgami, Z. Evaluation of Supporting Role of Early Enteral Feeding via Tube Jejunostomy Following Resection of Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2012, 26, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Shenoi, M.M.; Nussbaum, D.P.; Keenan, J.E.; Gulack, B.C.; Tyler, D.S.; Speicher, P.J.; Blazer, D.G. Feeding Jejunostomy Tube Placement during Resection of Gastric Cancers. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 200, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, K.; Lahoud, J.; Sandroussi, C.; Laurence, J.M.; Carey, S.; Yeo, D. Jejunostomy Feeding Tube Placement in Gastrectomy Procedures: A Systematic Review. Open J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 7, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yu, J.-C.; Kang, W.-M.; Ma, Z.-Q. Short-Term Effects of Supplementary Feeding with Enteral Nutrition via Jejunostomy Catheter on Post-Gastrectomy Gastric Cancer Patients. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 3297–3301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, X.; Yu, J.; Kang, W. Comparisons of Nutritional Status and Complications between Patients with and without Postoperative Feeding Jejunostomy Tube in Gastric Cancer: A Retrospective Study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 14, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhuo, Z.-G.; Li, G.; Alai, G.-H.; Song, T.-N.; Xu, Z.-J.; Yao, P.; Lin, Y.-D. Is the Routine Placement of a Feeding Jejunostomy during Esophagectomy Worthwhile?—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 4232–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddy, J.R.; Huddy, F.M.S.; Markar, S.R.; Tucker, O. Nutritional Optimization during Neoadjuvant Therapy Prior to Surgical Resection of Esophageal Cancer—A Narrative Review. Dis. Esophagus 2018, 31, doy110, Erratum in Dis. Esophagus 2018, 31, doy032. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doy032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okida, L.F.; Salimi, T.; Ferri, F.; Henrique, J.; Lo Menzo, E.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.J. Complications of Feeding Jejunostomy Placement: A Single-Institution Experience. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 3989–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Senesse, P.; Gioulbasanis, I.; Antoun, S.; Bozzetti, F.; Deans, C.; Strasser, F.; Thoresen, L.; Jagoe, R.T.; Chasen, M.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for the Classification of Cancer-Associated Weight Loss. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrup, J. Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS 2002): A New Method Based on an Analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, M. The “MUST” Report: Nutritional Screening of Adults: A Multidisciplinary Responsibility: Development and Use of the “Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool” (‘MUST’) for Adults; BAPEN: Redditch, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-899467-70-9. [Google Scholar]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN Practical Guideline: Clinical Nutrition in Cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Austin, P.; Boeykens, K.; Chourdakis, M.; Cuerda, C.; Jonkers-Schuitema, C.; Lichota, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Schneider, S.M.; Stanga, Z.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Home Enteral Nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccialanza, R.; Da Prat, V.; De Luca, R.; Weindelmayer, J.; Casirati, A.; De Manzoni, G. Nutritional Support via Feeding Jejunostomy in Esophago-Gastric Cancers: Proposal of a Common Working Strategy Based on the Available Evidence. Updat. Surg. 2025, 77, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case (Gender, Age) | Tumor Site | Dysphagia | Comorbidities | n. of Days Between T0 and Death | Pre-Illness BMI | BMI at T0 | Weight Loss (%) | NRS-2002 Score | MUST Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n.1 (M, 70) | Stomach | No | None | - | 26.2 | 22.3 | 14.9 | 4 | 1 |

| n.2 (M, 66) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids and liquids | COPD | - | 30.5 | 23.7 | 22.1 | 4 | 4 |

| n.3 (M, 61) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids | Peripheral vascular disease, history of stroke or TIA | 90 | 28.4 | 26.5 | 6.5 | 2 | 1 |

| n.4 (M, 80) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids | None | - | 27.7 | 24.6 | 11.3 | 5 | 2 |

| n.5 (M, 68) | Stomach | No | Myocardial infarction | - | 29.6 | 28.4 | 4.2 | 1 | 0 |

| n.6 (M, 66) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids | myocardial infarction | - | 33.2 | 27.7 | 16.5 | 3 | 2 |

| n.7 (M, 56) | Stomach | Dysphagia to solids | None | - | 26.6 | 23.4 | 12 | 2 | 2 |

| n.8 (M, 70) | Esophagus | Dysphagia to solids | None | - | 24.7 | 23.7 | 4.3 | 2 | 0 |

| n.9 (M, 47) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids | Chronic hepatitis | 97 | 27.8 | 25.5 | 8.2 | 2 | 1 |

| n.10 (M, 57) | EGJ | No | None | - | 33.8 | 30.4 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| n.11 (F, 48) | Esophagus | Dysphagia to solids and liquids | None | 60 | 27.7 | 21.4 | 22.9 | 4 | 4 |

| n.12 (M, 67) | GEJ | Dysphagia to solids | Uncomplicated diabetes mellitus | - | 25.1 | 21.3 | 15.1 | 3 | 2 |

| n.13 (F, 74) | Stomach | Dysphagia to solids and liquids | None | 174 | 22.3 | 17.6 | 21.1 | 5 | 6 |

| n.14 (M, 46) | GEJ | No | None | 297 | 25.4 | 21.1 | 16.9 | 3 | 2 |

| Case | Duration of Home Enteral Nutrition -HEN- (days) | FJ’s Use at T1 | FJ’s Use at T2 | FJ-Related Complications Requiring Hospitalization | Retention of FJ from Placement to Removal (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEN users for less than one month or non-users | |||||

| n.5 | no (never activated HEN) | no | no (never activated HEN) | none | 91 |

| n.10 | no (never activated HEN) | no | no (never activated HEN) | none | 94 |

| n.14 | 2 | yes | death | none | 288 |

| n.3 | 18 | yes | death | displacement | 81 |

| HEN users for more than one month | |||||

| n.8 | 36 | yes | no | none | 167 |

| n.11 | 43 | yes | yes | none | 54 |

| n.9 | 93 | yes | yes | none | 97 |

| n.7 | 97 | yes | yes | none | 98 |

| n.12 | 121 | yes | yes | leakage | 126 |

| n.1 | 129 | yes | yes | none | 208 |

| n.2 | 141 | yes | no | none | 143 |

| n.13 | 167 | yes | yes | none | 168 |

| n.4 | 217 | yes | no | infection and damage | 220 |

| HEN users with incomplete data | |||||

| n.6 | yes | missing | none | missing | missing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tieri, M.; Sivieri, C.; Viganò, J.; Corallo, S.; Dagnoni, A.; Pagani, A.; Mattavelli, E.; Uggè, A.; De Simeis, F.; Tartara, A.; et al. Nutritional Support via Jejunostomy Placed During Staging Laparoscopy for Esophagogastric Cancer: A Case Series. Healthcare 2026, 14, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010089

Tieri M, Sivieri C, Viganò J, Corallo S, Dagnoni A, Pagani A, Mattavelli E, Uggè A, De Simeis F, Tartara A, et al. Nutritional Support via Jejunostomy Placed During Staging Laparoscopy for Esophagogastric Cancer: A Case Series. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleTieri, Maria, Claudia Sivieri, Jacopo Viganò, Salvatore Corallo, Andrea Dagnoni, Anna Pagani, Elisa Mattavelli, Anna Uggè, Francesca De Simeis, Alice Tartara, and et al. 2026. "Nutritional Support via Jejunostomy Placed During Staging Laparoscopy for Esophagogastric Cancer: A Case Series" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010089

APA StyleTieri, M., Sivieri, C., Viganò, J., Corallo, S., Dagnoni, A., Pagani, A., Mattavelli, E., Uggè, A., De Simeis, F., Tartara, A., Pedrazzoli, P., Caccialanza, R., & Da Prat, V. (2026). Nutritional Support via Jejunostomy Placed During Staging Laparoscopy for Esophagogastric Cancer: A Case Series. Healthcare, 14(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010089