Leadership and Burnout in Anatomic Pathology Laboratories: Findings from Greece’s Attica Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Burnout in Pathology Laboratories

1.2. The Role of Leadership in Creating a Supportive Work Environment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Research Instruments

- (a)

- Demographic data: The first questionnaire, created by the research team, recorded participants’ demographic details: gender, age group, marital status, education level, employment setting (public, private, or university lab), type of employment, and years of experience in a pathology lab. Participants also indicated their professional role (physician, biologist, medical laboratory technologist, medical laboratory assistant, or administrative/secretarial staff). Finally, physicians were further classified by rank: those employed in the National Health System (NHS/ESY) included residents, auxiliary physicians, Registrar B, Registrar A, and directors (ESY rank); those in university labs included academic fellows, scientific associates, assistant professors, associate professors, and professors.

- (b)

- Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI): The second questionnaire we used was the CBI to measure the prevalence of occupational burnout. The instrument was developed by researchers at the National Institute of Occupational Health in Copenhagen [24] and originated from the Danish PUMA study (Project on Burnout, Motivation and Job Satisfaction), a 5-year longitudinal intervention launched in 1997 to examine burnout prevalence/distribution, causes, consequences, and interventions [24,25]

- (c)

- Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X): The third questionnaire used to determine the leadership model followed by each laboratory director is the third edition of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X). The instrument was originally developed in 1995 and has undergone two revisions, with the latest (2004) remaining in use to date [42,43]. The MLQ-5X has been widely used in research both in healthcare organizations [20,44,45,46,47,48] and in other sectors [49,50]. The MLQ includes 45 descriptive items. Participants rate how often each statement describes their department head using the following response categories: 0 = “Not at all”, 1 = “Once in a while”, 2 = “Sometimes”, 3 = “Fairly often”, 4 = “Frequently, if not always” (numeric values indicate scoring). The statements form nine subscales that correspond to three leadership style profiles: Transformational, Transactional, and Passive/Avoidant. Additionally, the MLQ includes three outcome variables: Extra Effort, Effectiveness, and Satisfaction, which reflect consequences of the leadership style (Table 2). Subscale and outcome scores were computed as the mean of the corresponding item ratings (0–4), following the official scoring instructions, with higher scores indicating greater levels of the construct. The licence to use the MLQ-5X was obtained from Mind Garden, Inc (Menlo Park, CA 94026 USA).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample’s Characteristics

3.2. Internal Consistency

3.3. Colleague-Related Burnout (Adaptation)

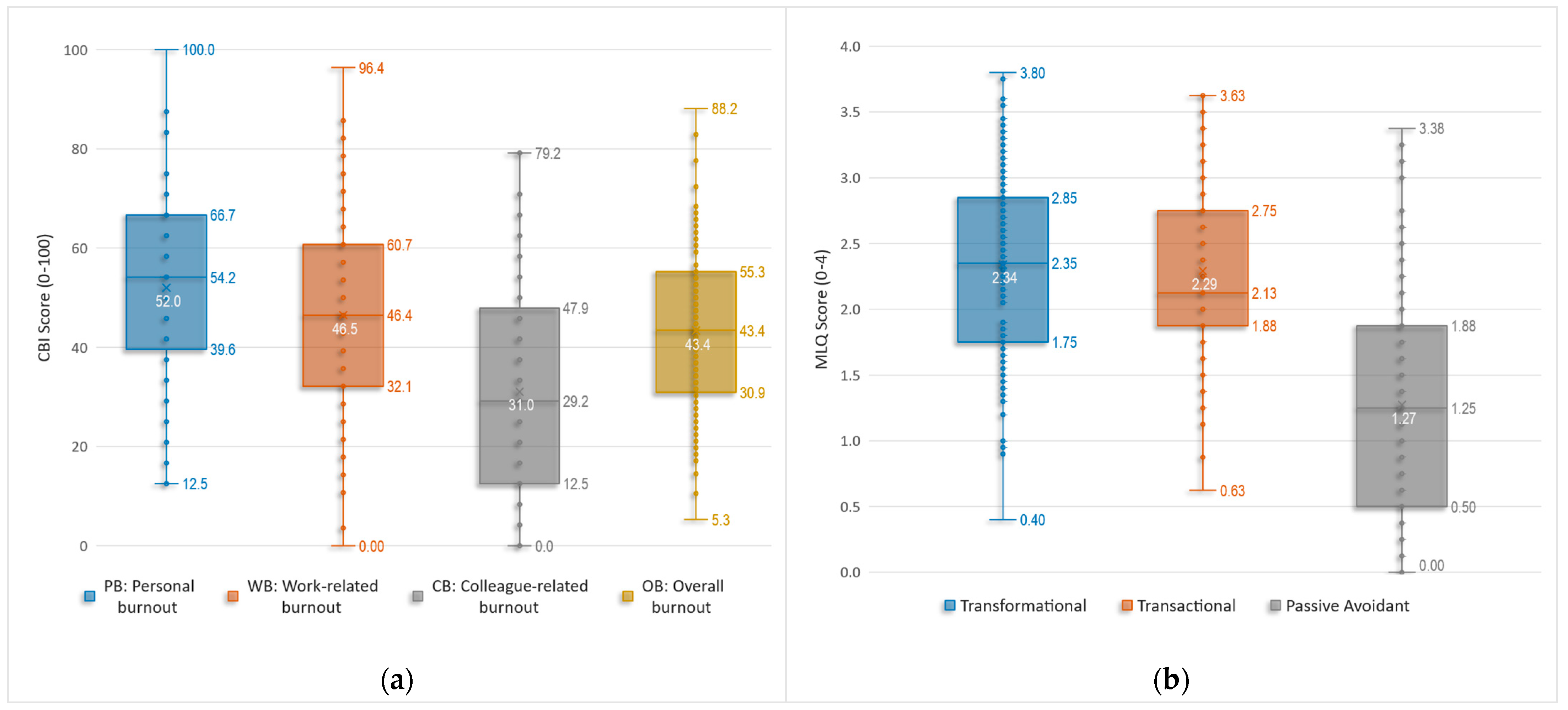

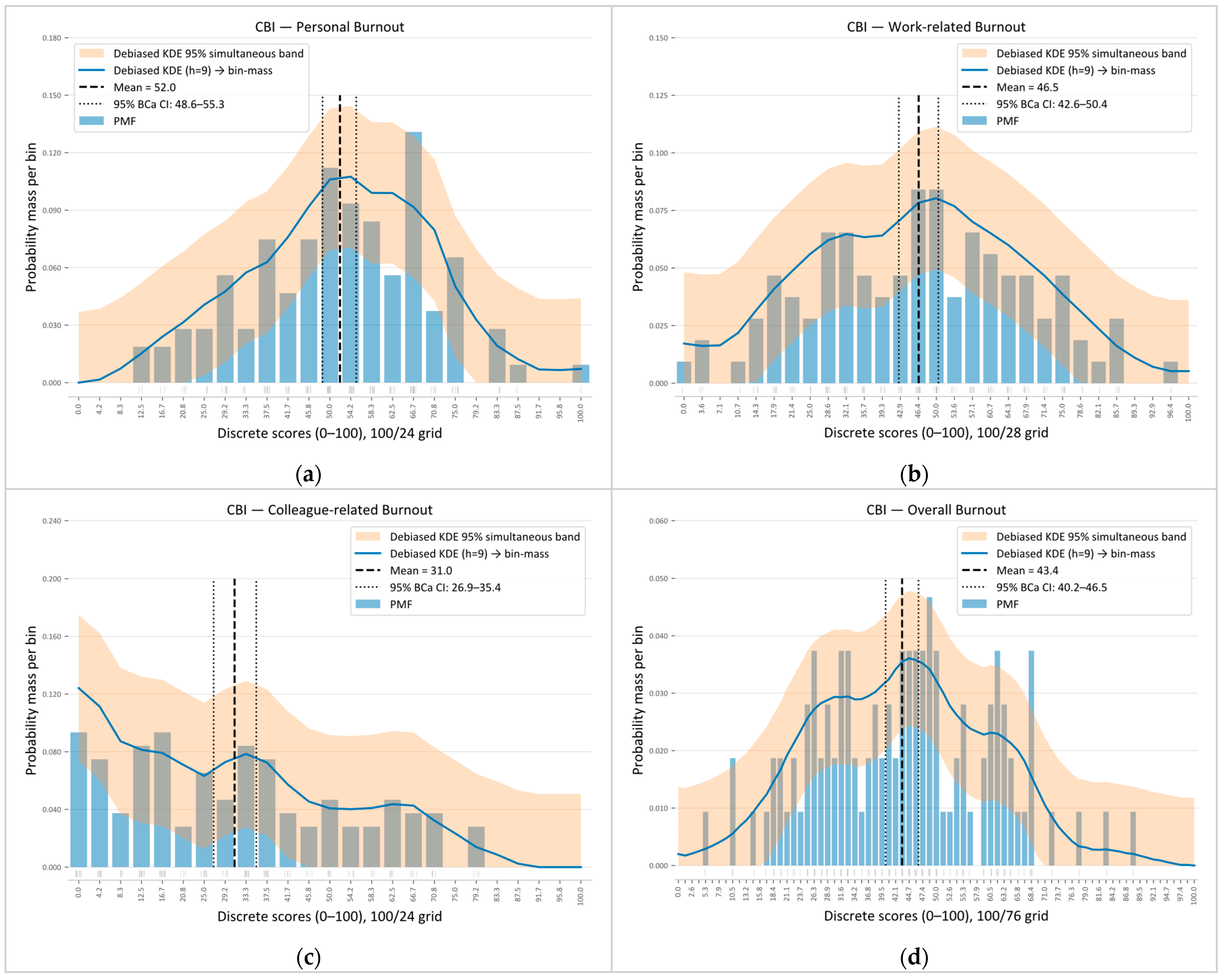

3.4. Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)

3.5. CBI Scales Scoring

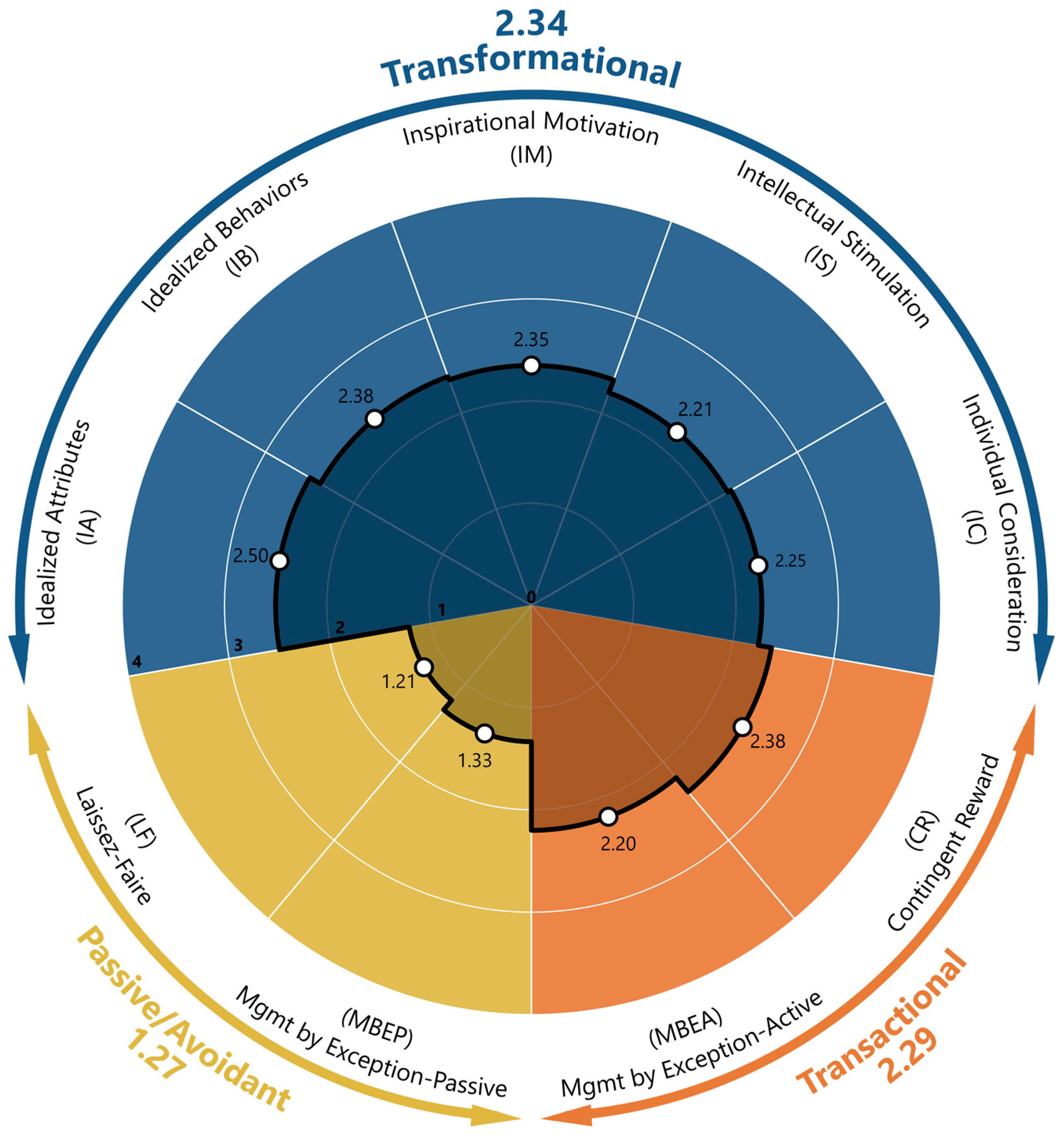

3.6. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X)

3.7. MLQ Leadership Styles Scores

3.8. Burnout–Leadership Correlations

3.9. Correlations with Demographic and Other Characteristics

3.10. Multiple Linear Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an Occupational Phenomenon. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Batanda, I. Prevalence of Burnout among Healthcare Professionals: A Survey at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital. npj Ment. Health Res. 2024, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipos, D.; Goyal, R.; Zapata, T. Addressing Burnout in the Healthcare Workforce: Current Realities and Mitigation Strategies. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 42, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaire, J.B.; Wallace, J.E. Burnout among Doctors. BMJ 2017, 358, j3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrijver, I. Pathology in the Medical Profession?: Taking the Pulse of Physician Wellness and Burnout. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, P.J.; Bridgeman, M.B.; Barone, J. Burnout Syndrome among Healthcare Professionals. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. AJHP Off. J. Am. Soc. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2018, 75, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatab, Z.; Hanna, K.; Rofaeil, A.; Wang, C.; Maung, R.; Yousef, G.M. Pathologist Workload, Burnout, and Wellness: Connecting the Dots. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2024, 61, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rawahi, S. Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction and Job Stress Among Omani Medical Laboratory Scientists; Karolinska Institutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Narainsamy, K.; Van Der Westhuizen, S. Work Related Well-Being: Burnout, Work Engagement, Occupational Stress and Job Satisfaction Within a Medical Laboratory Setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2013, 23, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Kundu, I.; Kelly, M.; Soles, R.; Mulder, L.; Talmon, G.A. The American Society for Clinical Pathology’s Job Satisfaction, Well-Being, and Burnout Survey of Laboratory Professionals. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprinca-Muja, L.-A.; Cristian, A.-N.; Topîrcean, E.; Cristian, A.; Popa, M.F.; Cardoș, R.; Oprinca, G.-C.; Atasie, D.; Mihalache, C.; Bucuță, M.D.; et al. Exploring Burnout at the Morgue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Three-Phase Analysis of Forensic and Pathology Personnel. Healthcare 2025, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Liauw, D.; Dupee, D.; Barbieri, A.L.; Olson, K.; Parkash, V. Burnout and Disengagement in Pathology: A Prepandemic Survey of Pathologists and Laboratory Professionals. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2023, 147, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Soles, R.; Garcia, E.; Kundu, I. Job Stress, Burnout, Work-Life Balance, Well-Being, and Job Satisfaction Among Pathology Residents and Fellows. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, J. The Burnout in Canadian Pathology Initiative. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 147, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, K.M.; Kanakis, C.E. Leadership Development for Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Residents and Fellows. Clin. Lab. Med. 2025, 45, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ghardallou, W.; Comite, U.; Ahmad, N.; Ryu, H.B.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Managing Hospital Employees’ Burnout through Transformational Leadership: The Role of Resilience, Role Clarity, and Intrinsic Motivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, K.; Barnard, J.G.; Tenney, M.; Holliman, B.D.; Morrison, K.; Kneeland, P.; Lin, C.-T.; Moss, M. Burnout and the Role of Authentic Leadership in Academic Medicine. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Song, J.; Shi, X.; Kan, C.; Chen, C. The Effect of Authoritarian Leadership on Young Nurses’ Burnout: The Mediating Role of Organizational Climate and Psychological Capital. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waraksa-Deutsch, T.L. Leading Medical Laboratory Professionals toward Change Readiness: A Correlational Study. Lab. Med. 2024, 55, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, D.A.; Boyd, J.; Madjlesi, R.; Greenspan, S.A.; Ezekiel-Herrera, D.; Potgieter, G.; Hammer, L.B.; Everson, T.; Lenhart, A. The Work-Life Check-Ins Randomized Controlled Trial: A Leader-Based Adaptive, Semi-Structured Burnout Intervention in Primary Care Clinics. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2024, 143, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.; Orsi, N.M. The Current Troubled State of the Global Pathology Workforce: A Concise Review. Diagn. Pathol. 2024, 19, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Noseworthy, J.H. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-Being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A New Tool for the Assessment of Burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borritz, M.; Rugulies, R.; Bjorner, J.B.; Villadsen, E.; Mikkelsen, O.A.; Kristensen, T.S. Burnout among Employees in Human Service Work: Design and Baseline Findings of the PUMA Study. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamis, D.; Minihan, E.; Hannan, N.; Doherty, A.M.; McNicholas, F. Burnout in Mental Health Services in Ireland during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, D.; Alshatti, F.; Alumran, A.; Al-Rayes, S.; Alsalman, D.; Althumairi, A.; Al-kahtani, N.; Aljabri, M.; Alsuhaibani, S.; Alanzi, T. Sociodemographic and Occupational Factors Associated With Burnout: A Study Among Frontline Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 854687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Millere, I.; Trups-Kalne, I. Adaptation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Latvia: Psychometric Data and Factor Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton, M.; Bou-Karroum, K.; Doumit, M.A.; Richa, N.; Alameddine, M. Determining Levels of Nurse Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Lebanon’s Political and Financial Collapse. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messias, E.; Gathright, M.M.; Freeman, E.S.; Flynn, V.; Atkinson, T.; Thrush, C.R.; Clardy, J.A.; Thapa, P. Differences in Burnout Prevalence between Clinical Professionals and Biomedical Scientists in an Academic Medical Centre: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachi, A.; Sikaras, C.; Ilias, I.; Panagiotou, A.; Zyga, S.; Tsironi, M.; Baras, S.; Tsitrouli, L.A.; Tselebis, A. Burnout, Depression and Sense of Coherence in Nurses during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žutautienė, R.; Radišauskas, R.; Kaliniene, G.; Ustinaviciene, R. The Prevalence of Burnout and Its Associations with Psychosocial Work Environment among Kaunas Region (Lithuania) Hospitals’ Physicians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Fatemi, A.; Sanches, M.; Howe, A.S.; Lo, J.; Jaswal, S.; Chattu, V.K.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Mental Health Outcomes among Electricians and Plumbers in Ontario, Canada: Analysis of Burnout and Work-Related Factors. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolatov, A.K.; Seisembekov, T.Z.; Askarova, A.Z.; Igenbayeva, B.; Smailova, D.S.; Hosseini, H. Psychometric Properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in a Sample of Medical Students in Kazakhstan. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2021, 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanneh, H.; Taimeh, Z.; Anas, S.; Bawadi, Y.; Al-Abcha, T.; Qaswal, A.B.; Bani Mustafa, R. Personality Traits & Their Relation to Academic Burnout and Satisfaction with Medicine as a Career in Jordanian Medical Students. Discov. Psychol. 2024, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Bani-Fatemi, A.; Howe, A.; Ubhi, S.; Morrison, M.; Saini, H.; Chattu, V.K. Examining Burnout in the Electrical Sector in Ontario, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwadiya, K.S.; Owoeye, O.K.; Adeoti, A.O. Evaluating the Factor Structure, Reliability and Validity of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (CBI-SS) among Faculty of Arts Students of Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.L.R.; de Jesus, L.C.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Henriques, S.H.; Marôco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Burnout Syndrome in University Professors and Academic Staff Members: Psychometric Properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory–Brazilian Version. Psicol. Reflex. E Crit. 2020, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarz, R.; Filipska, K.; Jabłońska, R.; Królikowska, A.; Szewczyk, M.T.; Wiśniewski, A.; Biercewicz, M. Analysis of Job Burnout, Satisfaction and Work-related Depression among Neurological and Neurosurgical Nurses in Poland: A Cross-sectional and Multicentre Study. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongtrakul, W.; Dangprapai, Y.; Saisavoey, N.; Sa-nguanpanich, N. Reliability and Validity Study of the Thai Adaptation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (CBI-SS) among Preclinical Medical Students at the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefstathiou, E.; Tsounis, A.; Malliarou, M.; Sarafis, P. Translation and Validation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory amongst Greek Doctors. Health Psychol. Res. 2019, 7, 7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1995; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3109405 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire: Manual and Sample Set; Mind Garden: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alluhaybi, A.; Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Wilson, A. Clinical Nurse Managers’ Leadership Styles and Staff Nurses’ Work Engagement in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Tremblay, P. Examining the Factor Structure of the MLQ Transactional and Transformational Leadership Dimensions in Nursing Context. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 41, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.R.; Rifkin, D.J.; Aslani, P.; McLachlan, A.J. Psychometric Properties of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire When Used in Early-Career Pharmacists with Provisional Registration. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2025, 21, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsiani, G.; Bagnasco, A.; Sasso, L. How Staff Nurses Perceive the Impact of Nurse Managers’ Leadership Style in Terms of Job Satisfaction: A Mixed Method Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poels, J.; Verschueren, M.; Milisen, K.; Vlaeyen, E. Leadership Styles and Leadership Outcomes in Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Esteve, M.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Measuring Leadership an Assessment of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, M.; Karavasilis, I. Leadership and Job Satisfaction: The Case of Civilian Technical Employees of the Ministry of National Defense. Proceedings 2025, 111, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Dong, J.; Gohar, B.; Hoad, M. Factors Associated with Burnout among Medical Laboratory Professionals in Ontario, Canada: An Exploratory Study during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2022, 37, 2183–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoglu, B.; Hassoy, H.; Gul, G.; Aykutlu, U.; Doganavsargil, B. How Does It Feel to Be a Pathologist in Turkey? Results of a Survey on Job Satisfaction and Perception of Pathology. Turk. Patoloji Derg. 2021, 37, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.; Boyaci, C.; Braun, M.; Pezzuto, F.; Zens, P.; Lobo, J.; Tiniakos, D. Breaking Barriers in Pathology: Bridging Gaps in Multidisciplinary Collaboration. Virchows Arch. 2025, 487, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehr, H.-A.; Bosman, F.T. Communication Skills in Diagnostic Pathology. Virchows Arch. 2016, 468, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawahi, S.; Sellgren, S.F.; Altouby, S.; Alwahaibi, N.; Brommels, M. Stress and Job Satisfaction among Medical Laboratory Professionals in Oman: A Cross-Sectional Study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonert, M.; Zafar, U.; Maung, R.; El-Shinnawy, I.; Kak, I.; Cutz, J.-C.; Naqvi, A.; Juergens, R.A.; Finley, C.; Salama, S.; et al. Evolution of Anatomic Pathology Workload from 2011 to 2019 Assessed in a Regional Hospital Laboratory via 574,093 Pathology Reports. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metter, D.M.; Colgan, T.J.; Leung, S.T.; Timmons, C.F.; Park, J.Y. Trends in the US and Canadian Pathologist Workforces From 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e194337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroft, S.H. Well-Being, Burnout, and the Clinical Laboratory. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloubani, A.; Akhu-Zaheya, L.; Abdelhafiz, I.M.; Almatari, M. Leadership Styles’ Influence on the Quality of Nursing Care. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2019, 32, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.E.; Van Dam, P.J.; Kitsos, A. Measuring Transformational Leadership in Establishing Nursing Care Excellence. Healthcare 2019, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomboy, F.; Palutturi, S.; Rifai, F.; Saleh, L.M.; Nasrul; Amiruddin, R. Leadership Style Based on the Study of Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire in Palu Anutapura Hospital. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, S432–S434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.; Montgomery, A.; Murray, S.; Peters, S.; Halcomb, E. Exploring Leadership in Health Professionals Following an Industry-based Leadership Program: A Cross-sectional Survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 4747–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.B.; Bøgh Andersen, L. Is Leadership in the Eye of the Beholder? A Study of Intended and Perceived Leadership Practices and Organizational Performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahum-Shani, I.; Somech, A. Leadership, OCB and Individual Differences: Idiocentrism and Allocentrism as Moderators of the Relationship between Transformational and Transactional Leadership and OCB. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, A.A.; Tullai-McGuinness, S.; Anthony, M.K. Nurses’ Perception of Their Manager’s Leadership Style and Unit Climate: Are There Generational Differences? J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkin, T.R.; Tracey, J.B. The Relevance of Charisma for Transformational Leadership in Stable Organizations. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1999, 12, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.J.; Hearld, L.R. Burnout and Leadership Style in Behavioral Health Care: A Literature Review. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 47, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángeles López-Cabarcos, M.; López-Carballeira, A.; Ferro-Soto, C. How to Moderate Emotional Exhaustion among Public Healthcare Professionals? Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.; Glazer, S.; Leiva, D. Leaders Condition the Work Experience: A Test of a Job Resources-Demands Model Invariance in Two Countries. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1353289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S.; Aleksić, V.S.; Slavković, M. “Direct Me or Leave Me”: The Effect of Leadership Style on Stress and Self-Efficacy of Healthcare Professionals. Behav. Sci. 2024, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosak, J.; Kilroy, S.; Chênevert, D.; Flood, P.C. Examining the Role of Transformational Leadership and Mission Valence on Burnout among Hospital Staff. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2021, 8, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, M.L.; Cozzolino, M.R.; Carini, E.; Di Pilla, A.; Galletti, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G. Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Results of a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CBI Burnout Scale | Items | Scoring Rate per Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | ||

| Personal burnout (PB) | PB.1-PB.6 | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| Work-related burnout (WB) | WB.1-WB.3 | To a very low degree | To a low degree | Somewhat | To a high degree | To a very high degree |

| WB.4-WB.6 | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| WB.7 | Always | Often | Sometimes | Seldom | Never | |

| Colleague-related burnout (CB) | CB.1-CB.4 | To a very low degree | To a low degree | Somewhat | To a high degree | To a very high degree |

| CB.5-CB.6 | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Leadership Style (Abbreviation) | MLQ-5X Subscale/Outcome | Abbreviation | No. of Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational (TRF) | Idealized Attributes | IA | 4 |

| Idealized Behaviors | IB | 4 | |

| Inspirational Motivation | IM | 4 | |

| Intellectual Stimulation | IS | 4 | |

| Individual Consideration | IC | 4 | |

| Transactional (TRN) | Contingent Reward | CR | 4 |

| Management by Exception–Active | MBEA | 4 | |

| Passive/Avoidant (PAS) | Management by Exception–Passive | MBEP | 4 |

| Laissez-Faire | LF | 4 | |

| Outcomes | Extra Effort | EF | 3 |

| Effectiveness | EFF | 4 | |

| Satisfaction with the Leader | SAT | 2 |

| Characteristic | N | % | Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Employment type | ||||

| Male | 39 | 36.4% | Permanent | 59 | 55.1% |

| Female | 68 | 63.6% | Non-permanent | 48 | 44.9% |

| Marital status | Tenure (years) | ||||

| Married | 60 | 56.1% | (0–5] | 38 | 35.5% |

| Single | 47 | 43.9% | (5–10] | 18 | 16.8% |

| Specialty | (10–15] | 18 | 16.8% | ||

| Doctors | 47 | 43.9% | (15–20] | 12 | 11.2% |

| Other Staff | 60 | 56.1% | (20+] | 21 | 19.6% |

| Scale (Subscale) | α | Scale (Subscale) | α | Scale (Subscale) | α | Scale (Subscale) | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB | 0.92 | TRF | 0.92 | TRN | 0.70 | PAS | 0.88 |

| (PB) | 0.88 | (IA) | 0.87 | (CR) | 0.61 | (MBEP) | 0.69 |

| (WB) | 0.88 | (IB) | 0.67 | (MBEA) | 0.58 | (LF) | 0.85 |

| (CB) | 0.89 | (IM) | 0.85 | ||||

| (IS) | 0.73 | ||||||

| (IC) | 0.57 |

| CBI | Cronbach’s α | Inter-Item Correlations | Corrected Item-Total Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | If Item Deleted | Mean | Min | (Min with) | Max | (Max with) | |

| CB.1 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.54 | CB.4 | 0.73 | CB.2 | 0.77 |

| CB.2 | 0.87 | 0.60 | 0.44 | CB.4 | 0.73 | CB.1 | 0.71 |

| CB.3 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.59 | CB.2 | 0.69 | CB.1 | 0.78 |

| CB.4 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.44 | CB.2 | 0.63 | CB.3 | 0.60 |

| CB.5 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.48 | CB.4 | 0.77 | CB.6 | 0.75 |

| CB.6 | 0.87 | 0.60 | 0.44 | CB.4 | 0.77 | CB.5 | 0.72 |

| Overall | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.44 | CB.2–CB.4 | 0.77 | CB.5–CB.6 | 0.72 |

| Questionnaire Item | Response Category (%) | IMC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (f): | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always |  | |

| (d): | To a Very Low Degree | To a Low Degree | Somewhat | To a Very Low Degree | To a Low Degree | ||

| (Rate = 0) | (Rate = 25) | (Rate = 50) | (Rate = 75) | (Rate = 100) | |||

| PB.1 How often do you feel tired? | (f) | 1.9 | 5.6 | 31.8 | 50.4 | 10.3 |  |

| PB.2 How often are you physically exhausted? | (f) | 2.8 | 15.0 | 41.1 | 36.4 | 4.7 |  |

| PB.3 How often are you emotionally exhausted? | (f) | 0.9 | 25.2 | 40.2 | 26.2 | 7.5 |  |

| PB.4 How often do you think “I cannot take it anymore”? | (f) | 10.3 | 31.8 | 32.7 | 21.5 | 3.7 |  |

| PB.5 How often do you feel worn out? | (f) | 1.9 | 17.8 | 43.9 | 32.7 | 3.7 |  |

| PB.6 How often do you feel weak and susceptible to illness? | (f) | 10.3 | 41.2 | 35.5 | 12.1 | 0.9 |  |

| WB.1 Is your work emotionally exhausting? | (d) | 10.3 | 17.8 | 33.6 | 28.0 | 10.3 |  |

| WB.2 Do you feel burnt out because of your work? | (d) | 7.5 | 23.4 | 28.0 | 30.8 | 10.3 |  |

| WB.3 Does your work frustrate you? | (d) | 24.3 | 33.7 | 25.2 | 10.3 | 6.5 |  |

| WB.4 Do you feel worn out at the end of the working day? | (f) | 2.8 | 18.7 | 34.6 | 34.6 | 9.3 |  |

| WB.5 Are you exhausted in the morning at the thought of another day at work? | (f) | 13.1 | 36.5 | 27.1 | 16.8 | 6.5 |  |

| WB.6 Do you feel that every working hour is tiring for you? | (f) | 9.3 | 36.5 | 27.1 | 20.6 | 6.5 |  |

| WB.7 Do you have enough energy for family and friends during leisure time? | (f*) | Always 13.1 | Often 32.7 | Sometimes 36.5 | Seldom 14.0 | Never 3.7 |  |

| CB.1 Do you find it hard to work with your colleagues? | (d) | 30.8 | 29.9 | 24.3 | 15.0 | 0.0 |  |

| CB.2 Do you find working with your colleagues frustrating? | (d) | 41.2 | 29.9 | 18.7 | 9.3 | 0.9 |  |

| CB.3 Does working with your colleagues drain your energy? | (d) | 33.7 | 28.0 | 26.2 | 9.3 | 2.8 |  |

| CB.4 Do you feel you give more than you get back when working with your colleagues? | (d) | 23.3 | 23.4 | 18.7 | 16.8 | 17.8 |  |

| CB.5 Are you tired of working with your colleagues? | (f) | 35.5 | 31.8 | 24.3 | 8.4 | 0.0 |  |

| CB.6 Do you ever wonder how long you will be able to keep working with your colleagues? | (f) | 36.5 | 27.1 | 22.4 | 13.1 | 0.9 |  |

| CBI | Mean | BCa 95% CI | SD | Median | Min | Max | Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis | Shapiro–Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | W | p | ||||||||

| Personal (PB) | 52.0 | 48.6 | 55.3 | 17.7 | 54.2 | 12.5 | 100.0 | 87.5 | −0.13/−0.25 | 0.99 | 0.29 |

| Work-related (WB) | 46.5 | 42.6 | 50.4 | 20.7 | 46.4 | 0.0 | 96.4 | 96.4 | 0.00/−0.55 | 0.99 | 0.59 |

| Colleague-related (CB) | 31.0 | 26.9 | 35.4 | 22.5 | 29.2 | 0.0 | 79.2 | 79.2 | 0.41/−0.87 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Overall (OB) | 43.4 | 40.2 | 46.5 | 16.7 | 43.4 | 5.3 | 88.2 | 82.9 | 0.15/−0.36 | 0.99 | 0.71 |

| Leadership Style | Subscales and Outcomes | Response Category (%) | IMC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All | Once in a While | Sometimes | Fairly Often | Frequently, If Not Always |  | ||

| (Rate = 0) | (Rate = 1) | (Rate = 2) | (Rate = 3) | (Rate = 4) | |||

| Transformational (TRF) | IA | 7.5 | 15.7 | 23.8 | 25.5 | 27.5 |  |

| IB | 7.0 | 15.7 | 27.8 | 31.0 | 18.5 |  | |

| IM | 9.3 | 19.4 | 24.5 | 31.8 | 15.0 |  | |

| IS | 7.2 | 20.6 | 31.3 | 25.2 | 15.7 |  | |

| IC | 11.2 | 16.8 | 26.6 | 26.2 | 19.2 |  | |

| Transactional (TRN) | CR | 8.4 | 17.5 | 22.9 | 29.7 | 21.5 |  |

| MBEA | 9.6 | 18.7 | 30.8 | 23.8 | 17.1 |  | |

| Passive/ Avoidant (PAS) | MBEP | 31.9 | 26.9 | 22.2 | 13.6 | 5.4 |  |

| LF | 37.2 | 25.2 | 21.7 | 11.0 | 4.9 |  | |

| Outcomes | EF | 13.1 | 13.4 | 31.7 | 23.1 | 18.7 |  |

| EFF | 4.9 | 8.6 | 28.7 | 28 | 29.8 |  | |

| SAT | 4.2 | 9.3 | 25.2 | 30.9 | 30.4 |  | |

| MLQ-5X Construct | Mean | SD | BCa 95% CI | Median | Min | Max | Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis | Shapiro–Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | W | p | ||||||||

| Leadership Style | |||||||||||

| TRF | 2.34 | 0.75 | 2.20 | 2.48 | 2.35 | 0.40 | 3.80 | 3.40 | −0.16/−0.58 | 0.99 | 0.33 |

| TRN | 2.29 | 0.67 | 2.16 | 2.42 | 2.13 | 0.63 | 3.63 | 3.00 | 0.03/−0.55 | 0.98 | 0.08 |

| PAS | 1.27 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 1.44 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 3.38 | 3.38 | 0.27/−0.82 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Subscale | |||||||||||

| IA | 2.50 | 1.05 | 2.30 | 2.70 | 2.75 | 0.25 | 4.00 | 3.75 | −0.31/−0.83 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| IB | 2.38 | 0.80 | 2.23 | 2.53 | 2.50 | 0.25 | 4.00 | 3.75 | −0.23/−0.50 | 0.98 | 0.08 |

| IM | 2.35 | 0.97 | 2.17 | 2.52 | 2.50 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | −0.32/−0.65 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| IS | 2.21 | 0.85 | 2.06 | 2.37 | 2.25 | 0.25 | 4.00 | 3.75 | 0.06/−0.26 | 0.98 | 0.20 |

| IC | 2.25 | 0.79 | 2.10 | 2.41 | 2.25 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 0.01/−0.57 | 0.98 | 0.21 |

| CR | 2.38 | 0.82 | 2.23 | 2.54 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 3.50 | −0.01/−0.72 | 0.98 | 0.08 |

| MBEA | 2.20 | 0.77 | 2.05 | 2.35 | 2.25 | 0.00 | 3.75 | 3.75 | −0.30/−0.24 | 0.98 | 0.09 |

| MBEP | 1.33 | 0.86 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 0.22/−0.74 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| LF | 1.21 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.39 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.43/−0.62 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Outcome | |||||||||||

| EE | 2.21 | 0.81 | 2.05 | 2.37 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | −0.46/−0.02 | 0.97 | 0.01 |

| EFF | 2.69 | 0.95 | 2.50 | 2.88 | 2.75 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | −0.32/−0.67 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| SAT | 2.74 | 0.90 | 2.57 | 2.91 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 3.50 | −0.37/−0.54 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| MLQ-5X Construct | Burnout (CBI) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Work-Related | Colleague-Related | Overall | |||||||||

| r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | |

| Leadership Style | ||||||||||||

| TRF | −0.24 | −0.41 | −0.05 | −0.30 | −0.47 | −0.10 | −0.34 | −0.50 | −0.17 | −0.36 | −0.52 | −0.20 |

| TRN | −0.13 | −0.31 | 0.06 | −0.20 | −0.38 | −0.01 | −0.25 | −0.42 | −0.08 | −0.24 | −0.40 | −0.07 |

| PAS | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.55 |

| Subscale | ||||||||||||

| IA | −0.29 | −0.45 | −0.11 | −0.35 | −0.51 | −0.17 | −0.35 | −0.52 | −0.18 | −0.41 | −0.55 | −0.26 |

| IB | −0.08 | −0.25 | 0.10 | −0.16 | −0.31 | 0.02 | −0.23 | −0.41 | −0.05 | −0.20 | −0.36 | −0.01 |

| IM | −0.21 | −0.38 | −0.02 | −0.26 | −0.42 | −0.07 | −0.26 | −0.43 | −0.08 | −0.30 | −0.45 | −0.12 |

| IS | −0.24 | −0.43 | −0.04 | −0.29 | −0.47 | −0.11 | −0.35 | −0.50 | −0.18 | −0.36 | −0.52 | −0.21 |

| IC | −0.16 | −0.34 | 0.02 | −0.19 | −0.36 | −0.01 | −0.23 | −0.39 | −0.05 | −0.24 | −0.38 | −0.06 |

| CR | −0.18 | −0.33 | −0.01 | −0.25 | −0.42 | −0.07 | −0.33 | −0.49 | −0.15 | −0.31 | −0.46 | −0.16 |

| MBEA | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.16 | −0.07 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.27 | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.26 | 0.08 |

| MBEP | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.53 |

| LF | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.52 |

| Outcome | ||||||||||||

| EE | −0.13 | −0.29 | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −0.19 | −0.35 | −0.01 | −0.16 | −0.31 | 0.01 |

| EFF | −0.28 | −0.43 | −0.10 | −0.33 | −0.48 | −0.16 | −0.39 | −0.54 | −0.23 | −0.41 | −0.54 | −0.27 |

| SAT | −0.29 | −0.46 | −0.10 | −0.41 | −0.57 | −0.23 | −0.37 | −0.54 | −0.20 | −0.44 | −0.59 | −0.29 |

| Participant Charecteristic | Copenhagen Burnout (CBI) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Work-Related | Colleague-Related | Overall | |||||||||

| r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | |

| Gender | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.40 | −0.02 | −0.20 | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.39 |

| Age | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.30 | −0.09 | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.22 | 0.18 |

| Marital status | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.24 | −0.07 | −0.25 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.20 | 0.17 |

| Specialty | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.26 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.23 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.34 | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.29 |

| Degree | −0.07 | −0.27 | 0.13 | −0.04 | −0.23 | 0.17 | −0.02 | −0.20 | 0.17 | −0.05 | −0.25 | 0.16 |

| Work Type | −0.23 | −0.40 | −0.05 | −0.18 | −0.36 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.21 | 0.18 | −0.17 | −0.35 | 0.02 |

| Tenure | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.32 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.24 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.25 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.28 |

| Perticipant Characteristic | MLQ Leadership Styles and Outcomes | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRF | TRN | PAS | EE | EFF | SAT | |||||||||||||

| r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | r | LB | UB | |

| Gender | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.18 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.26 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.21 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.28 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.18 | −0.03 | −0.20 | 0.16 |

| Age | 0.03 | −0.17 | 0.23 | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.27 | −0.08 | −0.25 | 0.09 | −0.14 | −0.31 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.23 | 0.17 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 0.24 |

| Marital status | −0.21 | −0.37 | −0.02 | −0.24 | −0.42 | −0.07 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.37 | −0.07 | −0.26 | 0.10 | −0.19 | −0.38 | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.31 | 0.07 |

| Specialty | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.37 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.33 | −0.08 | −0.26 | 0.12 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.37 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.31 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.31 |

| Degree | −0.15 | −0.33 | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.37 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.20 | 0.15 | −0.10 | −0.28 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.22 | 0.13 | −0.01 | −0.19 | 0.16 |

| Work Type | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.29 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.22 | −0.02 | −0.22 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 0.24 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.29 |

| Tenure | −0.14 | −0.32 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.30 | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.27 | −0.28 | −0.44 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.29 | 0.09 | −0.08 | −0.24 | 0.10 |

| Model | Predictor Variables | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI for B | TOL | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | |||||||||

| PB-1 | Summary: R2 = 0.14, adj. R2 = 0.11, SE = 16.66, ΔR2 = 0.14, ΔF(3, 103) = 5.51, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 48.54 | 3.30 | 14.71 | 0.00 | 41.99 | 55.08 | ||||

| Gender | 10.47 | 3.53 | 0.29 | 2.97 | 0.00 | 3.47 | 17.46 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Specialty | 0.48 | 3.42 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.89 | −6.29 | 7.26 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Employment type | −7.66 | 3.25 | −0.22 | −2.36 | 0.02 | −14.11 | −1.22 | 0.99 | 1.01 | |

| PB-2 | Summary: R2 = 0.20, adj. R2 = 0.15, SE = 16.29, ΔR2 = 0.06, ΔF(3, 100) = 2.55, p = 0.06, Durbin-Watson = 2.00 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 52.26 | 9.27 | 5.64 | 0.00 | 33.87 | 70.65 | ||||

| Gender | 9.57 | 3.48 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 0.01 | 2.66 | 16.49 | 0.88 | 1.13 | |

| Specialty | 2.14 | 3.42 | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.53 | −4.63 | 8.92 | 0.86 | 1.16 | |

| Employment type | −6.89 | 3.22 | −0.19 | −2.14 | 0.03 | −13.27 | −0.51 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| Transformational | −5.49 | 4.28 | −0.23 | −1.28 | 0.20 | −13.98 | 3.00 | 0.24 | 4.14 | |

| Transactional | 2.45 | 4.08 | 0.09 | 0.60 | 0.55 | −5.64 | 10.55 | 0.34 | 2.95 | |

| Passive/Avoidant | 2.20 | 2.43 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.37 | −2.63 | 7.03 | 0.55 | 1.80 | |

| WB-1 | Summary: R2 = 0.07, adj. R2 = 0.05, SE = 20.19, ΔR2 = 0.07, ΔF(3, 103) = 2.74, p = 0.05 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 44.09 | 4.00 | 11.03 | 0.00 | 36.16 | 52.02 | ||||

| Gender | 8.83 | 4.27 | 0.21 | 2.07 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 17.31 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Specialty | −0.20 | 4.14 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.96 | −8.41 | 8.01 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Employment type | −6.90 | 3.94 | −0.17 | −1.75 | 0.08 | −14.71 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 1.01 | |

| WB-2 | Summary: R2 = 0.18, adj. R2 = 0.13, SE = 19.25, ΔR2 = 0.11, ΔF(3, 100) = 4.43, p = 0.01, Durbin-Watson = 1.90 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 47.21 | 10.95 | 4.31 | 0.00 | 25.48 | 68.94 | ||||

| Gender | 7.62 | 4.12 | 0.18 | 1.85 | 0.07 | −0.55 | 15.79 | 0.88 | 1.13 | |

| Specialty | 2.13 | 4.04 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.60 | −5.88 | 10.13 | 0.86 | 1.16 | |

| Employment type | −6.00 | 3.80 | −0.14 | −1.58 | 0.12 | −13.54 | 1.54 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| Transformational | −5.66 | 5.06 | −0.21 | −1.12 | 0.27 | −15.69 | 4.37 | 0.24 | 4.14 | |

| Transactional | 1.42 | 4.82 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.77 | −8.14 | 10.99 | 0.34 | 2.95 | |

| Passive/Avoidant | 4.65 | 2.88 | 0.20 | 1.62 | 0.11 | −1.06 | 10.35 | 0.55 | 1.80 | |

| Model | Predictor Variables | B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI for B | TOL | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | |||||||||

| CB-1 | Summary: R2 = 0.03, adj. R2 = 0.00, SE = 22.49, ΔR2 = 0.03, ΔF(3, 103) = 1.04, p = 0.38 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 29.31 | 4.45 | 6.58 | 0.00 | 20.48 | 38.14 | ||||

| Gender | −3.39 | 4.76 | −0.07 | −0.71 | 0.48 | −12.84 | 6.05 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Specialty | 8.04 | 4.61 | 0.18 | 1.74 | 0.08 | −1.11 | 17.19 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Employment type | −1.39 | 4.39 | −0.03 | −0.32 | 0.75 | −10.09 | 7.31 | 0.99 | 1.01 | |

| CB-2 | Summary: R2 = 0.27, adj. R2 = 0.22, SE = 19.81, ΔR2 = 0.24, ΔF(3, 100) = 10.89, p < 0.001, Durbin-Watson = 2.01 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 23.21 | 11.27 | 2.06 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 45.58 | ||||

| Gender | −5.28 | 4.24 | −0.11 | −1.25 | 0.22 | −13.68 | 3.13 | 0.88 | 1.13 | |

| Specialty | 11.12 | 4.15 | 0.25 | 2.68 | 0.01 | 2.88 | 19.36 | 0.86 | 1.16 | |

| Employment type | −0.53 | 3.91 | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.89 | −8.29 | 7.23 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| Transformational | −4.47 | 5.20 | −0.15 | −0.86 | 0.39 | −14.80 | 5.85 | 0.24 | 4.14 | |

| Transactional | 1.07 | 4.96 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.83 | −8.78 | 10.92 | 0.34 | 2.95 | |

| Passive/Avoidant | 10.36 | 2.96 | 0.40 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 4.49 | 16.23 | 0.55 | 1.80 | |

| OB-1 | Summary: R2 = 0.07, adj. R2 = 0.04, SE = 16.41, ΔR2 = 0.07, ΔF(3, 103) = 2.46, p = 0.07 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 40.83 | 3.25 | 12.56 | 0.00 | 34.38 | 47.27 | ||||

| Gender | 5.49 | 3.47 | 0.16 | 1.58 | 0.12 | −1.40 | 12.38 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Specialty | 2.62 | 3.37 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.44 | −4.06 | 9.29 | 0.90 | 1.11 | |

| Employment type | −5.40 | 3.20 | −0.16 | −1.69 | 0.09 | −11.75 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.01 | |

| OB-2 | Summary: R2 = 0.26, adj. R2 = 0.21, SE = 14.86, ΔR2 = 0.19, ΔF(3, 100) = 8.52, p < 0.001, Durbin-Watson = 1.85 | |||||||||

| (Constant) | 41.23 | 8.45 | 4.88 | 0.00 | 24.45 | 58.00 | ||||

| Gender | 4.16 | 3.18 | 0.12 | 1.31 | 0.19 | −2.14 | 10.47 | 0.88 | 1.13 | |

| Specialty | 4.97 | 3.11 | 0.15 | 1.60 | 0.11 | −1.21 | 11.15 | 0.86 | 1.16 | |

| Employment type | −4.55 | 2.93 | −0.14 | −1.55 | 0.12 | −10.38 | 1.27 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| Transformational | −5.23 | 3.90 | −0.24 | −1.34 | 0.18 | −12.97 | 2.51 | 0.24 | 4.14 | |

| Transactional | 1.64 | 3.72 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.66 | −5.75 | 9.02 | 0.34 | 2.95 | |

| Passive/Avoidant | 5.68 | 2.22 | 0.30 | 2.56 | 0.01 | 1.27 | 10.08 | 0.55 | 1.80 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Flokou, A.; Pappa, S.; Aletras, V.; Niakas, D.A. Leadership and Burnout in Anatomic Pathology Laboratories: Findings from Greece’s Attica Region. Healthcare 2026, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010077

Flokou A, Pappa S, Aletras V, Niakas DA. Leadership and Burnout in Anatomic Pathology Laboratories: Findings from Greece’s Attica Region. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlokou, Angeliki, Sofia Pappa, Vassilis Aletras, and Dimitris A. Niakas. 2026. "Leadership and Burnout in Anatomic Pathology Laboratories: Findings from Greece’s Attica Region" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010077

APA StyleFlokou, A., Pappa, S., Aletras, V., & Niakas, D. A. (2026). Leadership and Burnout in Anatomic Pathology Laboratories: Findings from Greece’s Attica Region. Healthcare, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010077