Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Implement the Psychological Well-Being of Nursing Students: A Scoping Review

Highlights

- Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are increasingly integrated into nursing education; however, substantial heterogeneity exists in intervention protocols, duration, delivery modes, and facilitator training.

- The majority of studies focus on reducing psychological distress, whereas outcomes related to positive psychological well-being and core nursing competencies remain underexplored.

- Future research should broaden outcome assessment to include positive indicators of well-being aligned with the relational and humanistic dimensions of nursing practice (e.g., empathy, compassion satisfaction, self-efficacy).

- The development and curricular integration of theory-informed, population-specific mindfulness and self-compassion protocols may enhance standardization, student engagement, and comparability across studies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Review Question(s)

- Primary question:

- -

- Which mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are administered to nursing students to implement their psychological well-being (e.g., increased level of awareness, resilience, empathy, emotional intelligence, self-care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, reduced stress, anxiety, and self-efficacy)?

- Sub-questions:

- -

- Are the periods in which they are administered (academic year, internship, theoretical lessons, laboratory activities) specified?

- -

- Are any adverse events reported in studies that included mindfulness-based interventions for nursing students?

- -

- What measurement tools are given to students to assess the outcomes of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs)?

- -

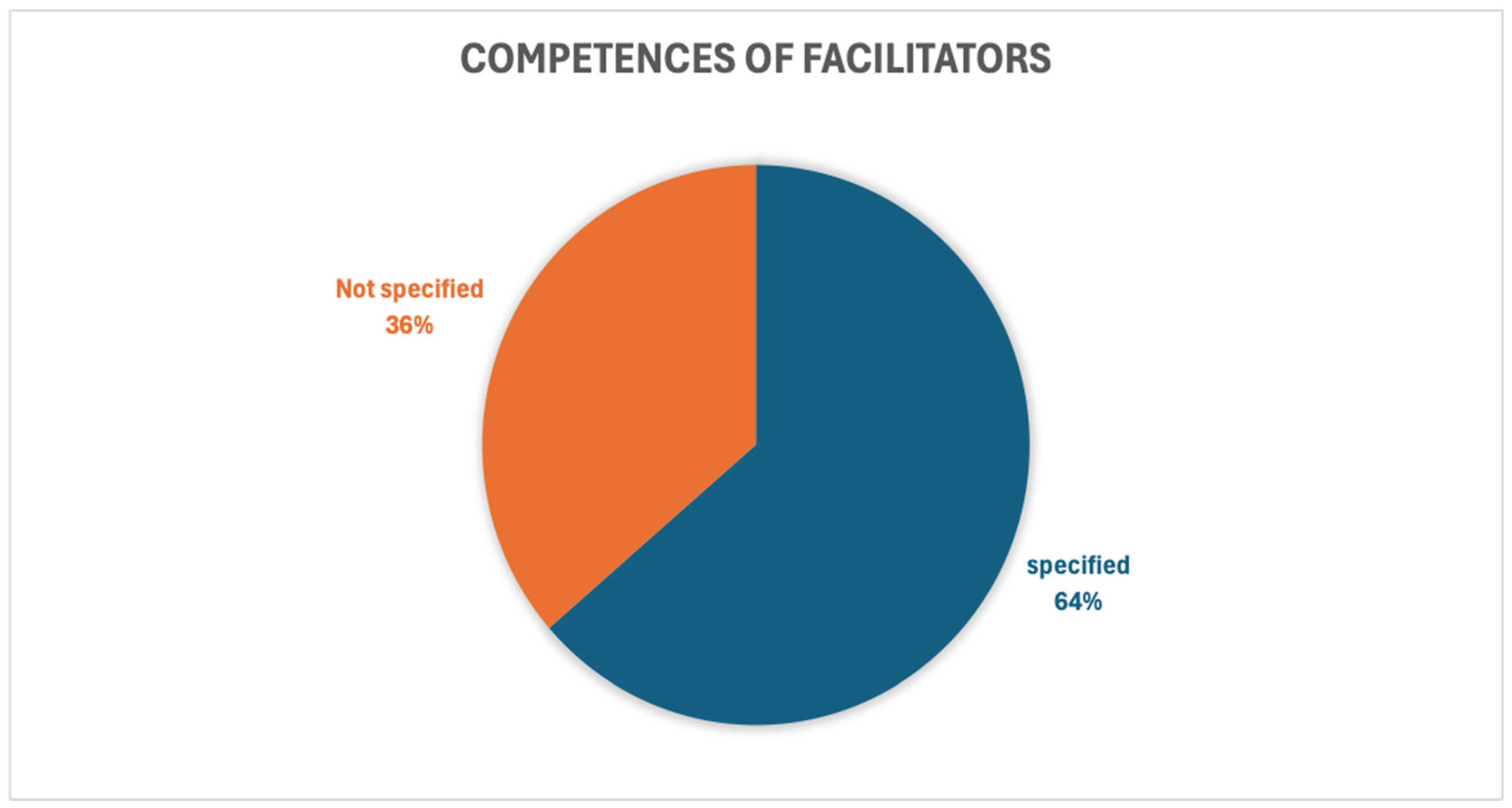

- Are the competencies of the mindfulness facilitator administering the intervention specified?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Types of Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study/Source of Evidence Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Analysis and Presentation

3. Results

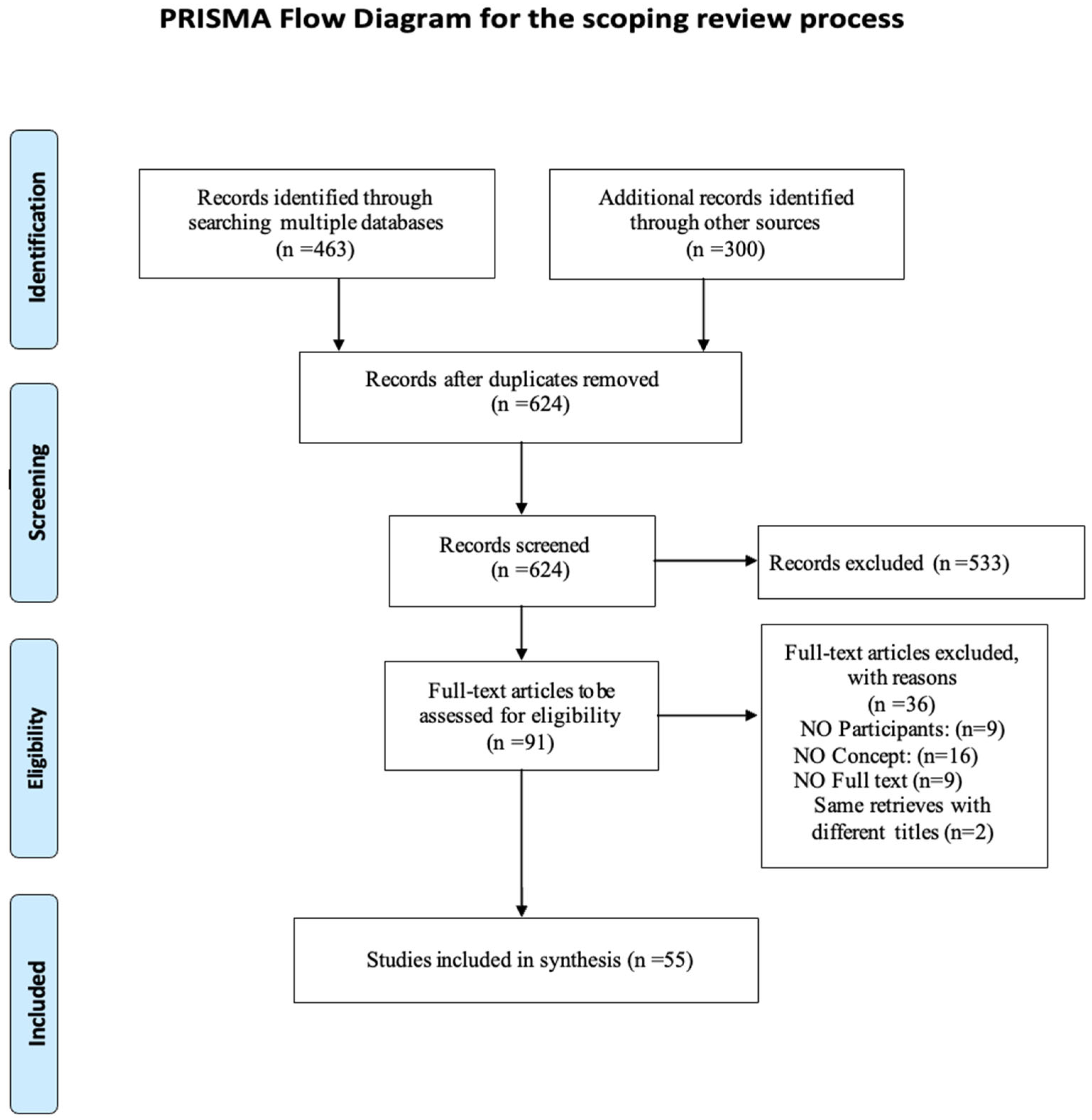

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Inclusion of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Review Findings

3.3.1. Study Characteristics

3.3.2. Participants in the Studies

3.3.3. Mindfulness-Based Interventions Applied

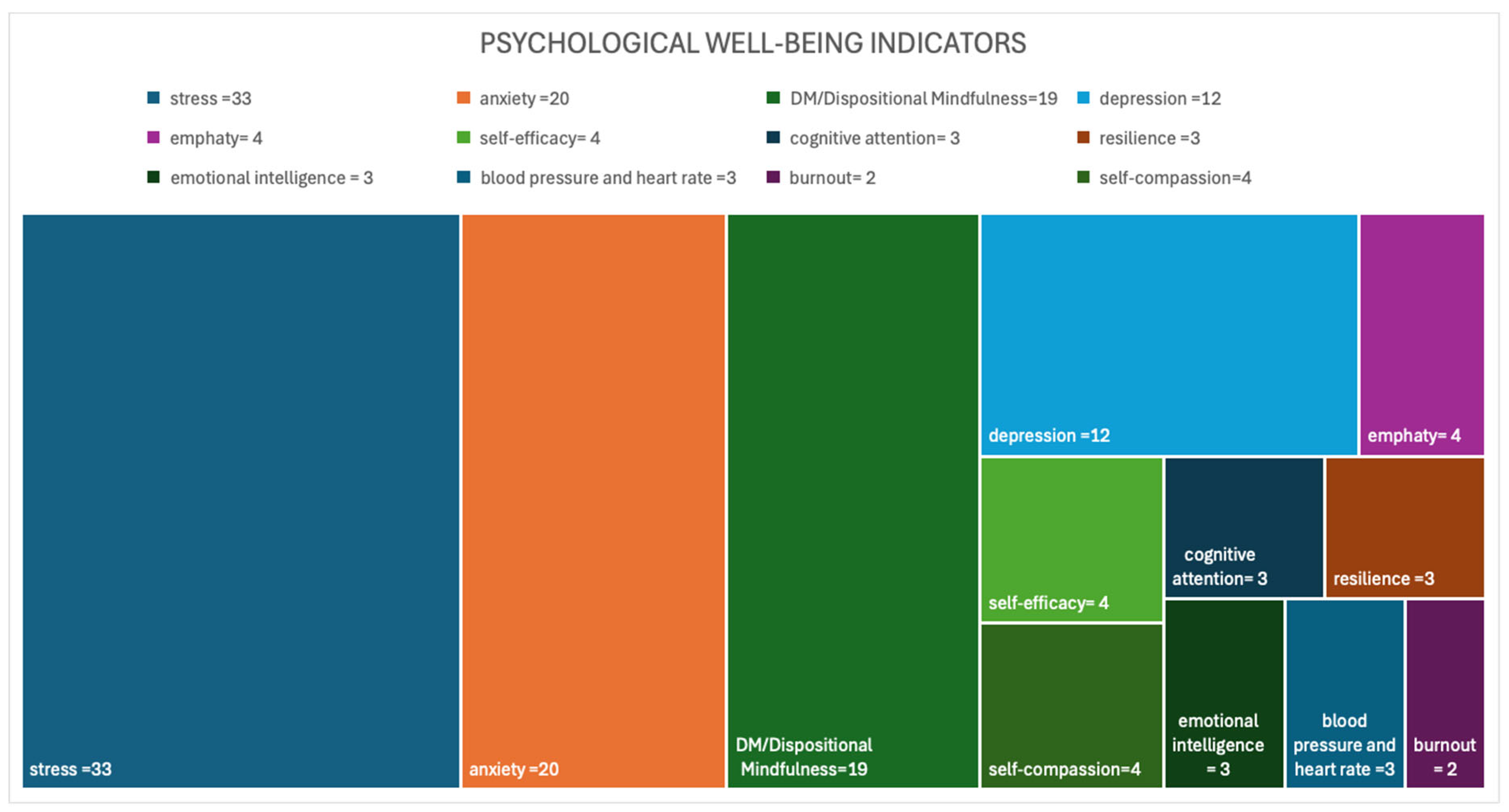

3.3.4. Outcomes

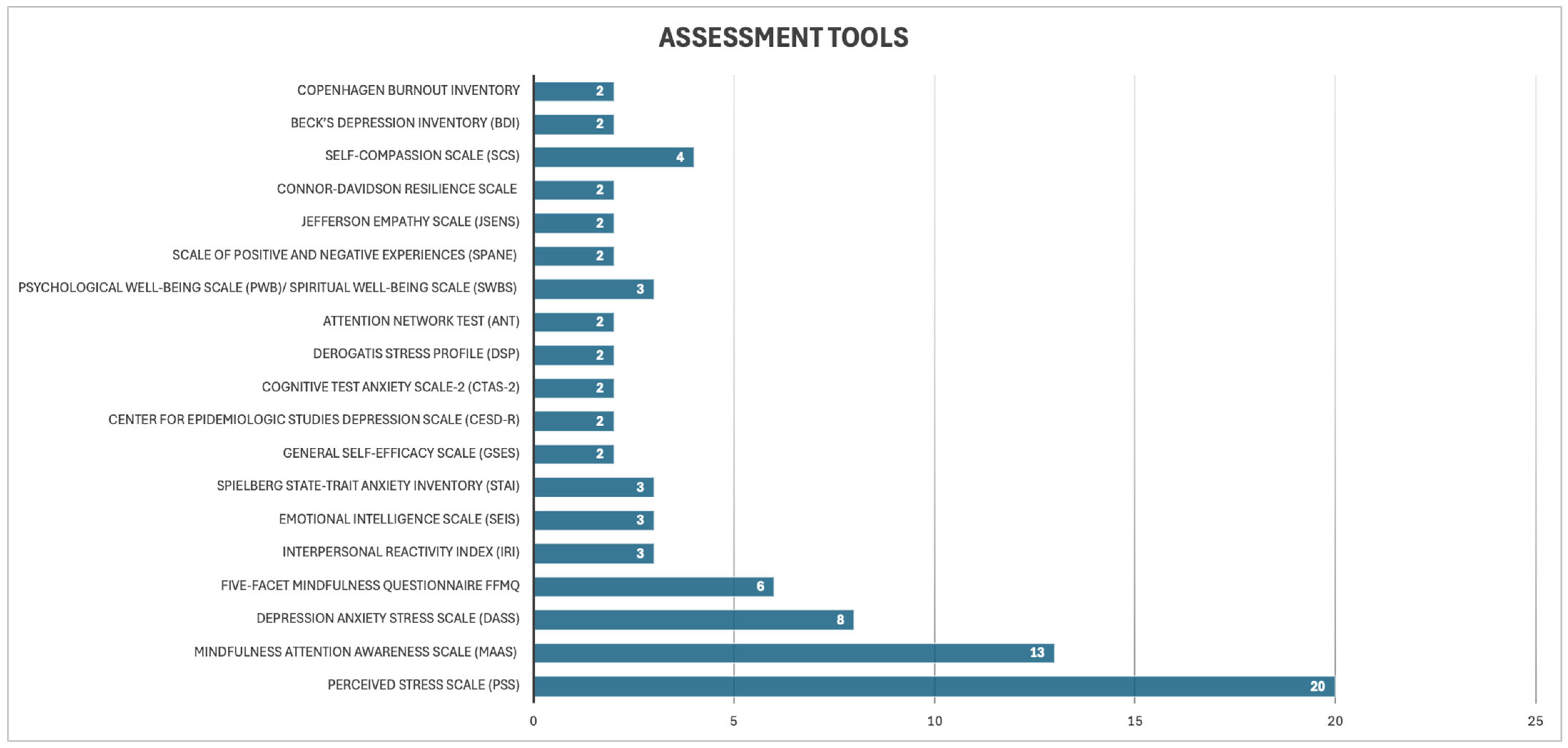

3.3.5. Assessment Tools

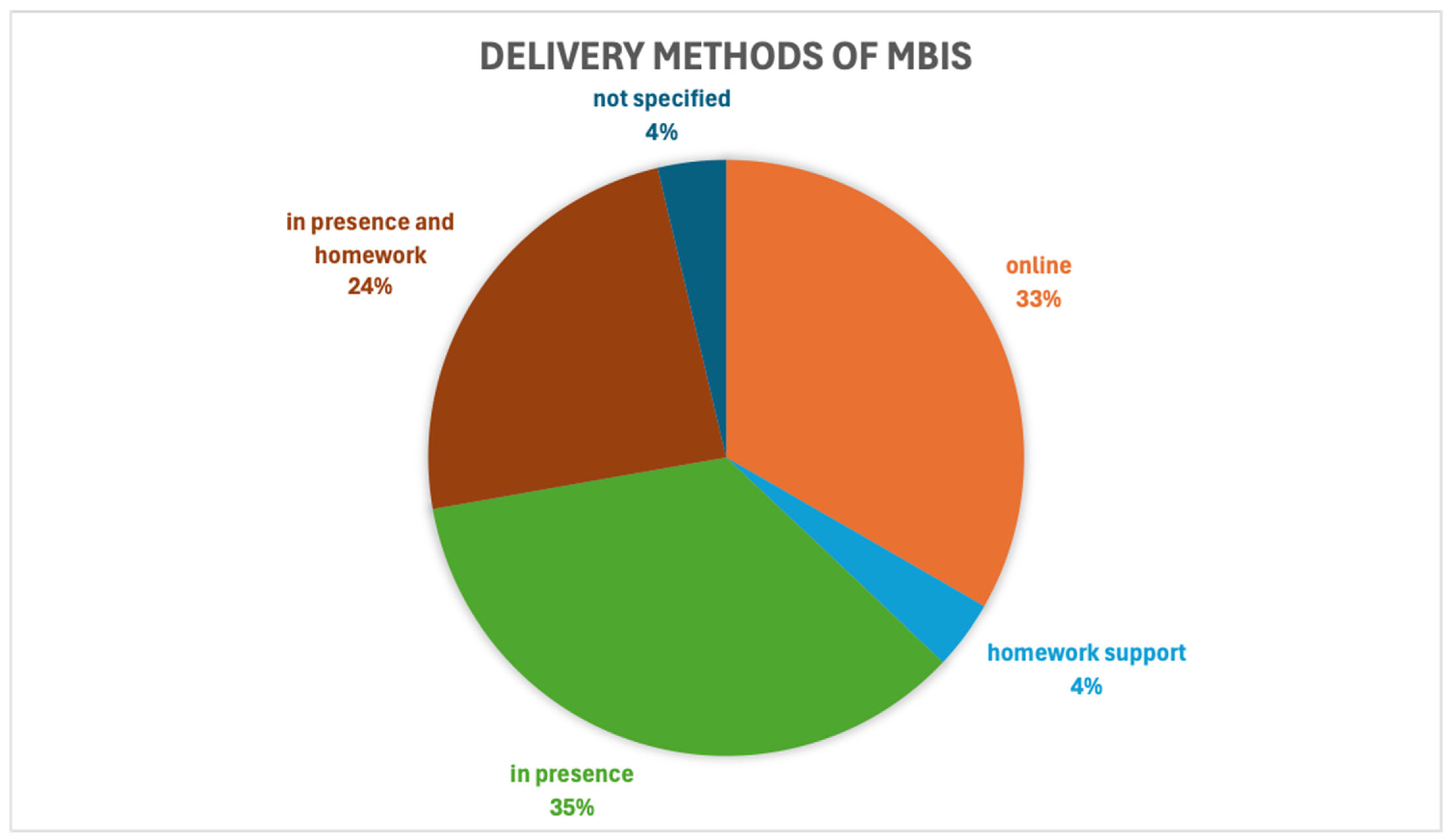

3.3.6. Delivery Method of Mindfulness-Based Interventions

3.3.7. Competencies of the Facilitators of Mindfulness-Based Interventions

3.3.8. Adverse Events

3.3.9. Intervention Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Intervention Characteristics and Outcomes of MBIs

4.2. Limitation of Scoping Review

4.3. Methodological Limitations of the Existing Literature

4.4. Implications for Education and Practice

4.5. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBIs | Mindfulness-Based Intervention |

| DM | Dispositional Mindfulness |

| MSC | Mindful Self Compassion |

| ScR | Scoping Review |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| MBCT | Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

Appendix A

Search Strategy

| Database | Search String |

| Pubmed | ((“nursing student*”[All Fields] OR “baccalaureate”[All Fields] OR “baccalaureates”[All Fields] OR “undergraduate nursing student”[All Fields] OR “pre-licensure”[All Fields]) AND (“mind s”[All Fields] OR “minded”[All Fields] OR “mindful”[All Fields] OR “mindfulness”[MeSH Terms] OR “mindfulness”[All Fields] OR “minding”[All Fields] OR “minds”[All Fields] OR (“self compassion”[MeSH Terms] OR “self compassion”[All Fields] OR (“self”[All Fields] AND “compassion”[All Fields]) OR “self compassion”[All Fields])) AND (“self care”[MeSH Terms] OR (“self”[All Fields] AND “care”[All Fields]) OR “self care”[All Fields] OR (“psychologic”[All Fields] OR “psychological”[All Fields] OR “psychologically”[All Fields] OR “psychologization”[All Fields] OR “psychologized”[All Fields] OR “psychologizing”[All Fields]) OR “well*”[All Fields] OR (“psychological well being”[MeSH Terms] OR (“psychological”[All Fields] AND “well being”[All Fields]) OR “psychological well being”[All Fields] OR (“psychological”[All Fields] AND “well”[All Fields]) OR “psychological well being”[All Fields]) OR (“self efficacy”[MeSH Terms] OR (“self”[All Fields] AND “efficacy”[All Fields]) OR “self efficacy”[All Fields]) OR (“stress”[All Fields] OR “stressed”[All Fields] OR “stresses”[All Fields] OR “stressful”[All Fields] OR “stressfulness”[All Fields] OR “stressing”[All Fields]) OR (“anxiety”[MeSH Terms] OR “anxiety”[All Fields] OR “anxieties”[All Fields] OR “anxiety s”[All Fields]) OR “emotional intelligence”[All Fields] OR (“empathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “empathy”[All Fields]) OR (“resilience, psychological”[MeSH Terms] OR (“resilience”[All Fields] AND “psychological”[All Fields]) OR “psychological resilience”[All Fields] OR “resilience”[All Fields] OR “resiliences”[All Fields] OR “resiliencies”[All Fields] OR “satisfaction compassion”[All Fields] OR (“fatiguability”[All Fields] OR “fatiguable”[All Fields] OR “fatigue”[MeSH Terms] OR “fatigue”[All Fields] OR “fatigued”[All Fields] OR “fatigues”[All Fields] OR “fatiguing”[All Fields] OR “fatigueability”[All Fields]) OR “resiliency”[All Fields] OR “resilient”[All Fields] OR “resilients”[All Fields])) AND (“hasabstract”[All Fields] AND “loattrfull text”[Filter]) AND (“hasabstract”[All Fields] AND “loattrfull text”[Filter])) AND ((fha[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter])) |

| Database | Search String |

| Cinahl | (nursing students or student nurses or undergraduate student nurses or pre-licensure nurse) AND (mindfulness based stress reduction or mindfulness or mbsr or mindfulness intervention or mindfulness-based interventions or mindful self-compassion or self compassion or self-compassion or MSC) AND (wellbeing or well-being or well being or quality of life or wellness or health or positive affect or mental health or psychological well-being or self-care) Limits: Abstract; full text |

| PsycInfo | (nursing students or student nurses or undergraduate student nurses or pre-registration nursing student) AND (mindfulness based stress reduction or mindfulness or mbsr or mindfulness intervention) OR (mindful self compassion or mindful self-compassion) AND (wellbeing or well-being or well being or quality of life or wellness or health or positive affect or mental health) AND (trial or study or experiment or treatment or intervention) Limits: link full-text |

| ProQuest | AB,TI(“nursing students”) AND (“mindfulness-based interventions” OR “mindful self-compassion”) AND (experimental study OR quasi-experimental study) Limit: full-text |

| ERIC | “nursing students” AND self-compassion |

| “nursing students” AND mindfulness | |

| Other retrivies | Search string |

| Google Scholar | “undergraduate nursing students” AND (“mindfulness-based interventions” OR “mindful self-compassion”) AND well-being Limits: 2020 |

References

- Mortari, L. La Pratica Dell’aver Cura, Ediz; MyLab: Milano/Torino, Italy, 2022; ISBN 9788891930996B. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.; Wand, T.; Fraser, J.A. On self-compassion and self-care in nursing: Selfish or essential for compassion-ate care? Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesak, S.S.; Morin, K.H.; Cutshall, S.M.; Jenkins, S.M.; Sood, A. Feasibility and efficacy of integrating resiliency training into a pilot nurse residency program. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 50, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E.; Proudfoot, J.; Lee, K.; Terterian, G.; Zisook, S. A longitudinal analysis of nurse suicide in the United States (2005–2016) with recommendations for action. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Chen, L.; Feng, F.; Okoli, C.T.C.; Tang, P.; Zeng, L.; Jin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Pérez-García, E.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Quality of Life in Nursing Professionals: Burnout, Fatigue, and Compassion Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Han, W.L.; Qin, W.; Yin, H.X.; Zhang, C.F.; Kong, C.; Wang, Y.L. Extent of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: A meta-analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch, C.; Galiana, L.; Doménech, P.; Sansó, N. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Compassion Satisfaction in Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review of the Literature Published During the First Year of the Pandemic. Healthcare 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubin, C.A. Steps toward a resilient future nurse workforce. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2023, 20, 20220057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. Sein und Zeit (trad. it.: Essere e Tempo); Longanesi: Milano, Italy, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, E. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Love and caring. Ethics of face and hand—An invitation to return to the heart and soul of nursing and our deep humanity. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2003, 27, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Human Caring Science; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, M.L.; Taylor, H.; Nelson, J.D. Comparison of Mental Health Characteristics and Stress Between Bacca-laureate Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Schwartz, G.E.; Bonner, G. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. J. Behav. Med. 1998, 21, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karyadi, K.A.; VanderVeen, J.D.; Cyders, M.A. A meta-analysis of the relationship between trait mindfulness and substance use behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 143, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvarani, V.; Ardenghi, S.; Rampoldi, G.; Bani, M.; Cannata, P.; Ausili, D.; Di Mauro, S.; Strepparava, M.G. Pre-dictors of psychological distress amongst nursing students: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 44, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardenghi, S.; Russo, S.; Luciani, M.; Salvarani, V.; Rampoldi, G.; Bani, M.; Ausili, D.; Di Mauro, S.; Strepparava, M.G. The association between dispositional mindfulness and empathy among undergraduate nursing students: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 15132–15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, T.; Jacobs, G. Curriculum design for person-centredness: Mindfulness training within a bachelor course in nursing. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrai, F.; Cenerelli, D.; Bergami, B.; Scalorbi, S. Mindfulness for Nursing Profession. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264352620_La_mindfulness_per_la_professione_infermieristica (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sist, L.; Savadori, S.; Grandi, A.; Martoni, M.; Baiocchi, E.; Lombardo, C.; Colombo, L. Self-Care for Nurses and Midwives: Findings from a Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloufi, M.A.; Jarden, R.J.; Gerdtz, M.F.; Kapp, S. Reducing stress, anxiety and depression in undergraduate nursing students: Systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 102, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Helmreich, I.; König, J.; Chmitorz, A.; Wessa, M.; Binder, H.; Lieb, K. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD013684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Beddoe, A.E.; Murphy, S.O. Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? J. Nurs. Educ. 2004, 43, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultas, M.W.; Boyd, E.; McGroarty, C. Evaluation of a Brief Mindfulness Intervention on Examination Anxiety and Stress. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 60, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burner, L.R.; Spadaro, K.C. Self-Care Skills to Prevent Burnout: A Pilot Study Embedding Mindfulness in an Undergraduate Nursing Course. J. Holist. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Holist. Nurses’ Assoc. 2023, 41, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiam, E.Y.X.; Lopez, V.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Perception on the mind-nurse program among nursing students: A descriptive qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 92, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Bi, T.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Xie, Q.; He, J. The impact of mindfulness training on supportive communication, emotional intelligence, and human caring among nursing students. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2552–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.H.Y.; Ho, L.M.K.; Lam, S.K.K.; Chan, C.K.Y.; Chan, M.M.K.; Pun, M.W.M.; Wang, K.M.P. Effectiveness and experiences of integrating Mindfulness into Peer-assisted Learning (PAL) in clinical education for nursing students: A mixed method study. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 132, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.; McKendrick-Calder, L.A.; Shumka, C.; McDonald, M.; Carlson, S. Managing student workload in clinical simulation: A mindfulness-based intervention. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 6, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, M.J.; Gerler, E.R., Jr. Using mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in individual counseling to reduce stress and increase mindfulness: An exploratory study with nursing students. Prof. Counselor. 2015, 5, 39–52. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/using-mindfulness-based-cognitive-therapy/docview/1658056047/se-2 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Uysal, N.; Çalışkan, B.B. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on mindfulness and stress levels of nursing students during first clinical experience. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2639–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of brief mindfulness meditation on anxiety symptoms and systolic blood pressure in Chinese nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.S.; Choi, S.Y.; Ryu, E. The effectiveness of a stress coping program based on mindfulness meditation on the stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by nursing students in Korea. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Lindquist, R. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindful-ness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhawatmeh, H.N.; Rababa, M.; Alfaqih, M.; Albataineh, R.; Hweidi, I.; Abu Awwad, A. The Benefits of Mindfulness Meditation on Trait Mindfulness, Perceived Stress, Cortisol, and C-Reactive Protein in Nursing Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2022, 13, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaraireh, F.A.; Aloush, S.M. Mindfulness Meditation Versus Physical Exercise in the Management of Depression Among Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2017, 56, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, K.G.; Lockhart, J.S. Meditation’s Effect on Attentional Efficiency, Stress, and Mindfulness Characteristics of Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2017, 56, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Gür, G.; Yilmaz, E. The effects of mindfulness-based empathy training on empathy and aged discrimination in nursing students: A randomised controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase-Cantarini, S.; Christiaens, G. Introducing mindfulness moments in the classroom. J. Prof. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Coll. Nurs. 2019, 35, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, S.; De Bartolo, P.; Agostini, A. Integrating mindfulness into nursing education: A pilot nonrandomized controlled trial. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2020, 27, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colburn, F.; Guerrazzi-Young, C.; Durant, D.J. Perceptions of Sandtray as a Component of a Mindful Self-Compassion Workshop to Reduce Burnout in Nursing Students. World J. Sand Ther. Pract. 2023, 1, 1–15. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9dca/6093871352b9f788b1c6ac0062694f4dfbdb.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Jing, S.; Wang, H.; Xiao, W.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Pan, C.; Tang, Q.; Wang, H.; et al. Mindfulness-based online intervention on mental health among undergraduate nursing students during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Beijing, China: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 949477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahem, S.M.; Abd-elwahab, S.D.; Shokr, E.A.; Radwan, H.A. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Skills on Self-Efficacy and Suicidal Ideation among First-Year Nursing Students with Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Egypt. J. Nurs. Sci. Res. 2022, 3, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElKayal, M.M.; Metwaly, S.M. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based intervention on post-traumatic stress symptoms among emergency nursing students. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, H. Testing the impact of an online mindfulness program on prelicensure nursing students stress and anxiety. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A.; Cunningham, T.; Millar, A.; McWhirter, C.; Hume, L.; Gaughan, M. Taking your time: Mindfulness for learning disability nursing students. Learn. Disabil. Pract. 2016, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, A.; Şişman, N.Y. Effects of a Stress Management Training Program with Mindfulness-Based Stress Re-duction. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiksou, J.; Maskour, L.; El Batri, B.; Alaoui, S. The effect of a mindfulness training program on perceived stress and emotional intelligence among nursing students in Morocco: An experimental pilot study. Acta Neuropsychol. 2022, 20, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munif, B.; Poeranto, S.; Utami, Y.W. Effects of Islamic Spiritual Mindfulness on Stress Among Nursing Students. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2019, 9, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ş. The effect of a distance-delivered mindfulness-based psychoeducation program on the psychological well-being, emotional intelligence and stress levels of nursing students in Turkey: A randomized controlled study. Health Educ. Res. 2023, 38, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatraro, M.; Gallegos, C.; Walters, R. A simple and accessible tool to improve student mental health wellbeing. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2024, 19, e444–e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanasiripong, P.; Park, J.F.; Ratanasiripong, N.; Kathalae, D. Stress and Anxiety Management in Nursing Students: Biofeedback and Mindfulness Meditation. J. Nurs. Educ. 2015, 54, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari Ozturk, C.; Kilicarslan Toruner, E. The effect of mindfulness-based mandala activity on anxiety and spiritual well-being levels of senior nursing students: A randomized controlled study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheick, D.M. Developing self-aware mindfulness to manage countertransference in the nurse-client relationship: An evaluation and developmental study. J. Prof. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Coll. -Es Nurs. 2011, 27, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, K.C.; Hunker, D.F. Exploring The effects Of An online asynchronous mindfulness meditation intervention with nursing students On Stress, mood, And Cognition: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarhan, M.; Elibol, E. The effect of a brief mindfulness-based stress reduction program on strengthening awareness of medical errors and risks among nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 70, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torné-Ruiz, A.; Reguant, M.; Roca, J. Mindfulness for stress and anxiety management in nursing students in a clinical simulation: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 66, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Bahadır Yılmaz, E. The effects of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 85, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M. Evaluating Mindfulness in the Classroom: Decreasing Nursing Student Perceived Stress. A DNP Final Project Submitted to the Faculty of Radford University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice in the School of Nursing. 2022. Available online: https://wagner.radford.edu/860/3/MArthur_Capstone_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Baich, V.A. Impacting Senior Student Test Anxiety by Implementing a Smartphone Mindfulness-Based Intervention in a Diploma Nursing Program. [Order No. 30423394]. American Sentinel University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/impacting-senior-student-test-anxiety/docview/2808745090/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Bonfe, L.L. Test Anxiety in Undergraduate Nursing Students: Implementation of a Brief Mindfulness Exercise. 2023. Available online: https://researchonline.stthomas.edu/esploro/outputs/workingPaper/Test-Anxiety-in-Undergraduate-Nursing-Students/991015225599503691?institution=01CLIC_STTHOMAS (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Davis, A. The Effects of a Web-Based Mindfulness Meditation on Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Undergraduate Pre-licensure Nursing Students: A Pilot Study (Order No. 27956568). University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-web-based-mindfulness-meditation-on/docview/2407269231/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Dodson, J. The Effects of Mindfulness on Test Anxiety in Nursing Students. A DNP Final Project Submitted to the School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Missouri-Kansas City in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10355/83241 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Foster, D.A. The Effects of Mindfulness Training on Perceived Level of Stress and Performance-Related Attributes in Baccalaureate Nursing Students (Order No. 10258800). Regent University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses 2017. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-mindfulness-training-on-perceived-level/docview/1885054302/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Heinrich, D.S. The Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on the Stress, Anxiety, Mindfulness, and Self-Compassion Levels of Nursing Students (Order No. 29163322). Teachers College, Columbia University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effect-mindfulness-meditation-on-stress-anxiety/docview/2682768437/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Kinney, S. The Effects of Abbreviated Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Empathy Growth of Prelicensure BSN Students (Order No. 28970879). Capella University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-abbreviated-mindfulness-based/docview/2642917270/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Klich, D.L. Investigation of the Relationship between Mindfulness and Empathy in Pre-nursing Students Exposed to a Four-Week Mindfulness Training (Order No. 27540090). The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/investigation-relationship-between-mindfulness/docview/2332129980/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Leggett, D.K. Effectiveness of a Brief Stress Reduction Intervention for Nursing Students in Reducing Physiological Stress Indicators and Improving Well-Being and Mental Health (Order No. 3432848). The University of Utah ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2010. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effectiveness-brief-stress-reduction-intervention/docview/853599664/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Lynch, M. Evidence Based Mindfulness Resource for Undergraduate Nursing Students. DNP Final Paper Submitted to the College of Nursing East Carolina University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice Program, 2023. Available online: https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/8252e6f2-eb7b-4601-afdb-ca2bbf90cf1c/content (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Medari, D. A Stress Management Intervention to Promote Self-Efficacy in an Associate Degree Nursing Program (Order No. 30631844). Regis College ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2023. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/stress-management-intervention-promote-self/docview/2871578214/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Oseguera, G. The Impact a Meditation Protocol has on Stress in Nursing Students in Southern California Nursing Schools (Order No. 13884136). Brandman University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/impact-meditation-protocol-has-on-stress-nursing/docview/2236460631/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Ross, J.C. Utility of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction to Impact Health Promotion in Nursing Students: A Mindful Project (Order No. 29993771). Azusa Pacific University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/utility-mindfulness-based-stress-reduction-impact/docview/2741306999/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Simonton, D.L. From Simulation Anxiety to COVID-19 Anxiety: The Perceptions of Pre-Licensure Nursing Students to Utilizing Brief Mindfulness Interventions as a Coping Mechanism (Order No. 28962999). Plymouth State University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/simulation-anxiety-covid-19-perceptions-pre/docview/2628790537/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Tenrreiro, K. The Impact of a Mindfulness Meditation Intervention on Cognitive Test Anxiety and the Academic Performance of Prelicensure Nursing Students Enrolled in an Associate Degree in Nursing Program (Order No. 29992321). Nova Southeastern University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/impact-mindfulness-meditation-intervention-on/docview/2786405193/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Teribury, V. Reducing Cognitive Test Anxiety in Nursing Students with Mindfulness Meditation (Order No. 28861970). Wilkes University The Passan School of Nursing ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/reducing-cognitive-test-anxiety-nursing-students/docview/2640986269/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Tung, L.N. Using Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) as a Strategy to Reduce Stress and Develop Self-Compassion in Nursing Students (Order No. 27837495). The Education University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong) ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/using-mindful-self-compassion-msc-as-strategy/docview/2458948204/se-2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornfield, J. Buddha’s Little Instruction Book; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell, S.B.; Vermeesch, A.L.; Scott, J.G. Interventions to reduce perceived stress among graduate students: A systematic review with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, C.; Ace, L.; Ski, C.F.; Carswell, C.; Burton, S.; Rej, S.; Noble, H. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Undergraduate Nursing Students in a University Setting: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, O.; Ramos, N.S.; Gonzalez-Moraleda, A.; Resurreccion, D.M. Brief mindfulness-based interventions in a laboratory context: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, P.C. Mindfulness and coping with dysphoric mood: Contrasts with rumination and distraction. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2005, 29, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, C.; Peltier, M.R.; Shah, S.; Kinsaul, J.; Waldo, K.; McVay, M.A.; Copeland, A.L. Effects of a brief mindfulness intervention on negative affect and urge to drink among college student drinkers. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 59, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.; Crane, C.; Miller, E.; Kuyken, W. Doing no harm in mindfulness-based programmes: Conceptual issues and empirical findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 71, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklitz, K.; Wong, G.; Howick, J. Mindfulness-based programmes to reduce stress and enhance well-being at work: A realist review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, A.; Kunstler, B.; Lennox, A.; Pattuwage, L.; Grundy, E.A.C.; Tsering, D.; Olivier, P.; Bragge, P. How effective are interventions in optimizing workplace mental health and well-being? A scoping review of reviews and evidence map. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2023, 49, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | No (%) | Country | No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA-United State of America [27,28,29,34,43,49,55,56,58,59,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] | 27 (49%) | Italy [44] | 1 (2%) |

| Turkey [35,42,51,54,57,60,62] | 7 (13%) | Hawaii [41] | 1 (2%) |

| China [30,31,32,36,46,80] | 6 (11%) | Marocco [52] | 1 (2%) |

| Egypt [47,48] | 2 (4%) | Oland [19] | 1 (2%) |

| Jordan [39,40] | 2 (4%) | Spain [61] | 1 (2%) |

| Korea [37,38] | 2 (4%) | Thailand [56] | 1 (2%) |

| Canada [33] | 1 (2%) | UK-United Kingdom [50] | 1 (2%) |

| Indonesia [53] | 1 (2%) |

| No. | First Author (Year) Country | Study Design | Sample Size Dropout Score | MBIs | Control | Outcome Measures (Variables) | Finding | Publication Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Niessen (2015) Oland [19] | MM | 201 E: 123; C: 78 Dropout rate (17.91%) E: −28 C: −8 | Mindfulness training | Wait list | QN: FFMQ-SF (Dispositional mindfulness); SCS1 (Self-compassion); QL: Inquiry (students’ perception) | QN: No statistically significant difference QL: MBIs benefited the students in personal and professional life. | Journal Article |

| 2 | Beddoe (2004) USA [27] | MM | 23 Dropout rate −7 (30%) | MBSR in presence and audio guide recorded at home | - | IRI (empathy); DSP (stress) | Significant reduced students’ anxiety. Reduced levels of anxiety and discomfort; improved levels of empathy and imagination. | Journal article |

| 3 | Bultas (2021) USA [28] | MM | 48 E: 24; C: 24 Dropout rate (18.75%) E: −9 C: 0 | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | Usual care | QN: MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); PSS (Stress); CD-RISC-10 (resilience); QL: Inquiry (students’ perception) | QN: An improvement in outcomes was observed but was not statistically significant. QL: greater sense of calm, confidence, awareness | Journal article |

| 4 | Burner (2023) USA [29] | QE | 67 Dropout rate −9 (13%) | Mindfulness Meditation and MBSR | - | PSS (Stress); MSCS (Self-care) | Statistically insignificant reduction in stress. Statistically significant impact on self-care after the practice. MSCS level decreased in follow-up | Journal article |

| 5 | Chiam (2020) China [30] | QL | 32 Dropout rate −12 (37.5%) | Mind-Nurse Program | - | Inquiry (students’ perception) | MBIs benefited the students in personal and professional life. | Journal Article |

| 6 | Kou (2022) China [31] | RCT | 60 E: 30; C: 30 Dropout rate (3.33%) E: −1; C: −1 | MBSR MBCT | Lecture on Mindfulness | SCS2 (Communication skills); EIS (Emotional intelligence); CAI (Human care) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 7 | Lam (2024) China [32] | MM | 126 Dropout rate −15 (12%) | Mindfulness-based PAL | OLBI-S (Burnout); DASS-21 (Depression, anxiety, stress); GSES (Self-efficacy) | QN: Statistically insignificant reduction in depression, anxiety and stress. Statistically significant impact on self-efficacy and burnout. QL: MBIs benefited the students in personal and professional life. | Journal Article | |

| 8 | Pollard (2020) Canada [33] | RCT | 120 E and C not specified Dropout rate −13 (11%) E: 86; C: 21 | Mindfulness moment before clinical simulation | No intervention | National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Learning Index (mental demands, physical demands, time demands, effort, performance, and frustration) | An improvement of workload demanded in two domains (temporal and exertion). | Journal Article |

| 9 | Schwarze (2015) USA [34] | QE | 5 Dropout rate −2 (40%) | MBCT Recorded guide on Podcast | - | MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); PSS (Stress) | An improvement of the investigated outcome | Journal Article |

| 10 | Uysal (2022) Turkey [35] | QE | 71 E and C: not specified Dropout rate −19 (27%) E: 17; C: 35 | MBSR | No intervention | PSS (Stress); PPSRS (student’s physical, psychological, and social health); MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 11 | Chen (2013) China [36] | RCT | 60 E: 30; C: 30 | Mindful breathing | No intervention | SAS (anxiety); SDS (depression); Physiological Measures: (Heart Rate; Blood Pressure) | A reduction in anxiety levels and blood pressure was observed. | Journal article |

| 12 | Kang (2019) Korea [37] | RCT | 41 E: 21; C: 20 Dropout rate (21.95%) E: −5; C: −4 | Stress Coping Program MBIs | Lecture on stress and coping | PWI-SF (Stress); STAI (Anxiety); BDI (Depression) Physiological Measures (Heart Rate; Blood Pressure) | Statistically insignificant reduction in depression, heart rate and blood pressure. Statistically significant impact on anxiety and stress. | Journal Article |

| 13 | Song (2015) Korea [38] | RCT | 50 E: 25; C: 25 Dropout rate (12%) E: −4; C: −2 | MBSR | Wait list | DASS-21(anxiety, stress, depression); MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 14 | Alhawatmeh (2022) Jordan [39] | RCT | 112 E: 56; C: 56 Dropout rate (3.57%) E: −2; C: −2 | Meditation “of the sense” ABC Relaxation Theory protocol | Sitting quietly with closed eyes | MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); PSS (Stress); Biomedical Markers (Cortisol and C-Reactive Protein) | Serum Cortisol level and perceived stress have been significantly reduced. DM and CRP did not reach statistically significant level. | Journal article |

| 15 | Alsaraireh (2017) Jordan [40] | RCT | 200 E: 100; C: 100 Dropout rate (9.5%) E: −9; C: −10 | Mindfulness Meditation | Physical exercises | CESD-R(Depression) | Experimental group showed a significantly greater reduction in their depression score than the Control group. | Journal article |

| 16 | Burger (2017) Hawaii [41] | RCT | 60 E: 32; C: 28 Dropout rate (13.33%) E: −4 C: −4 | Mindfulness Meditation online and recording | Wait list | ANT (attention); PSS (Stress); FFMQ (dispositional mindfulness) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal article |

| 17 | Can Gür (2020) Turkey [42] | RCT | 132 E and C not specified Dropout rate −9 (7%) E: 61; C: 62 | MBET | No intervention | JSENS (empathy); ADAS (Age discrimination) | Significant increase in the level of empathy in the Experimental group. No significant change in total age discrimination scores was recorded in either group | Journal article |

| 18 | Chase-Cantarini (2019) USA [43] | QL | 64 Dropout rate Not specified | Mindfulness moments | Survey (stress, fatigue, engagement, focus, learning skills | Very popular with most students. A student did not like it; some felt sleepy. Some suggestions have been made for implementing mindfulness moments | Journal article | |

| 19 | Cheli (2020) Italy [44] | RCT | 82 E: 36; C: 46 Dropout rate (8.53%) E: −2; C: −5 | MBEP (SANP) | Normal Educational Practice | CBI (Burnout); MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal article |

| 20 | Colburn (2023) USA [45] | QL | 69 Dropout rate Not specified | Mindful Self-Compassion Workshop with sandtray | - | Inquiry (students’ perception) | The participants appreciated the sandtray component, finding it useful for reflecting on strengths, life, emotions and experiences, and for expressing themselves. | Journal Article |

| 21 | Dai (2022) China [46] | RCT | 120 E: 60; C: 60 Dropout rate (10%) E: −8, C: −4 | MLWC | Health Education | DASS-21 (anxiety, stress, depression); FFMQ-SF ((dispositional mindfulness); PSSS (perceived social support) | Statistically insignificant reduction in depression. Statistically significant impact on anxiety, stress and awareness. | Journal Article |

| 22 | Ebrahem (2022) Egypt [47] | QE | 78 Dropout rate −1 (1.28%) | Mindfulness Practices | - | AOCS (Obsessive-compulsive symptoms); SSI (Suicidal ideation); SES (Self-efficacy); MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness) | The MBIs had a positive effect on improving self-efficacy and decreasing suicidal ideation and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. | Journal Article |

| 23 | ElKayal (2022) Egypt [48] | QE | 160 8 clusters with 20 participants per cluster Dropout rate Not specified | Theoretical session and Mindfulness Practices | - | IES-R (Post-traumatic stress) FFMQ-15 (Dispositional Mindfulness) | PTS symptoms and DM improved significantly after the application of MBIs. | Journal Article |

| 24 | Franco (2022) USA [49] | QE | 76 Dropout rate Not specified | TAO | - | DASS-21 (Depression, anxiety, stress); CSI-SF (Positive coping) | An improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 25 | Hutchison (2016) UK [50] | QE | 25 Dropout rate −5 (20%) | Mindfulness in Learning Disability Practice Workshop | - | A combination of open-ended questions and a Likert scale (Provocative behaviours; calm; dispositional mindfulness) | Positive effects of the workshop support the idea of embedding mindfulness training in the nursing curriculum. | Journal Article |

| 26 | Karaca (2019) Turkey [51] | RCT | 114 E: 42; C: 72 Dropout rate (8.77%) E: −3; C: −7 | MBSR | No intervention | Nursing Education Stress Scale (Academic stress); MAAS (Mindfulness skills); Stress Management Styles Scale (coping styles); | Statistically significant improvement on stress and awareness | Journal Article |

| 27 | Ksiksou (2022) Marocco [52] | QE | 20 Dropout rate Not specified | MBSR | PSS-CP (Stress); EIS (Emotional intelligence) | An improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article | |

| 28 | Munif (2019) Indonesia [53] | QE | 36 E: 18; C: 18 | Islamic spiritual mindfulness | No intervention | DASS-42 (Stress) | An improvement of the investigated outcome | Journal Article |

| 29 | Öztürk (2023) Turkey [54] | RCT | 64 E and C not specified Dropout rate −5 (8%) E: 29; C: 30 | Adapted MBSR | No intervention | PSS (Stress); PWB (Psychological Well-Being); SEIS (emotional intelligence) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 30 | Quatraro (2024) USA [55] | QE | 35 Dropout rate −9 (25.71%) | Mindfulness exercise Pre-recorded audio files | - | PSS (Stress); SCS (Self-Compassion); BDI (Depression) | Statistically significant improvement on stress and depression levels. An improvement of self-compassion. | Journal Article |

| 31 | Ratanasiripong (2015) Thailand [56] | RCT | 89 E1: 29 E2: 29 C: 29 | E-1: Biofeedback E-2: Vipassana Meditation | No intervention | Improvement of academic performance; PSS (Stress); STAI (Anxiety) | Mindfulness Meditation improved anxiety and stress levels | Journal Article |

| 32 | Sari Ozturk (2022) Turkey [57] | RCT | 180 E: 90; C: 90 Dropout rate (5,55%) E: −6; C: −4 | Mindfulness-based mandalas | No intervention | STAI (Anxiety); SWBS (Spiritual well-being); SPANE (Emotional management) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 33 | Scheick (2011) USA [58] | MM | 30 E and C not specified Dropout rate −8 (27%) E: 15; C: 7 | STEDFAST S-AM | - | Element S: Self-concept examination by Schutz (Dispositional mindfulness, self-control, reflective attention) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 34 | Spadaro (2016) USA [59] | QE | 27 Dropout rate −1(3.70%) | MBSR | - | PSS (Stress); HADS (Depression and anxiety); ANT (attention) | Statistically significant decrease in stress scores. Statistically insignificant decrease in stress scores. The ability to attention is improved. | Journal Article |

| 35 | Tarhan (2023) Turkey [60] | QE | 78 E: 36; C: 42 Dropout rate Not specified | Short form MBSR | Traditional teaching on clinical errors | Attitudes Medical Error Scales (medical error); Student Satisfaction and Self-confidence Scale in Learning (Self-confidence); Simulation Design Scale (errors and risks in a simulation environment) | Statistically significant improvement for medical error attitudes. Statistically insignificant difference for self-confidence and satisfaction. | Journal Article |

| 36 | Torné-Ruiz (2023) Spain [61] | QE | 52 E: 26 C: 26 Dropout rate (19.23%) E: −5; C: −5 | 10-daymindfulness | - | Self-administered Analogue Stress Scale (Stress); STAI (Anxiety); FFMQ (Awareness); Physiological Measures: (Blood Pressure) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 37 | Yüksel (2020) Turkey [62] | QE | 82 E: 41; C: 41 Dropout rate Not specified | MBCT | - | MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); DASS-21(anxiety, stress) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Journal Article |

| 38 | Arthur (2022) USA [63] | RCT | 57–60 Unclear | A record on Mindful Breathing | Relaxing music | Improvement of academic performance; MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); PSS (Stress) | No improvement in outcomes was observed | Doctoral dissertations |

| 39 | Baich (2022) USA [64] | QE | 34 Dropout rate −9 (26%) | Mindfulness guide with smartphone | - | WTAS (anxiety) | Statistically significant impact on the reduction in anxiety score | Doctoral dissertations |

| 40 | Bonfe (2023) USA [65] | MM | 24 Dropout rate Not specified | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | - | QN: DASS-21(anxiety, stress, depression); QL: Inquiry (students’ perception) | QN: Statistically insignificant reduction in anxiety and stress QL: Increased sense of calm, relaxation, centering, focusing. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 41 | Davis (2020) USA [66] | RCT | 120 12 clusters with 10 participants per cluster Dropout rate Not specified | Koru Mindfulness Meditation | Wait list | DASS-21 (stress; depression); ER (resilience); Brief COPE (coping strategies); ISEL-12 (personal resources and social support); SPANE (positive and negative emotions); PSS (burden of academic requirements); HPLP II (interpersonal relationships) | The MBIs was effective in lowering stress and depressive symptoms in nursing students. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 42 | Dodson (2021) USA [67] | QE | 40 Dropout rate Not specified | MBSR: Burdick’s Workbook | - | TAI (anxiety; emotionality, worries) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 43 | Foster (2017) USA [68] | RCT | 12 E: 6; C: 6 | Theoretical session and Mindfulness Practices | Self-managed study with supervision | DSP (Stress, anxiety); LASSI (Learning and time management strategies) | An improvement of the investigated outcomes in Experimental group. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 44 | Heinrich (2022) USA [69] | RCT | 195 E: 99; C: 96 Dropout rate (25.64%) E: −17; C: −33 | Listening to 10 min of Meditation recording | Listening to 10 min recording on nursing notions | PSS (Stress) SCS1 (Self-compassion) MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); GAD-7 (Anxiety) | Statistically significant improvement of the investigated outcomes | Doctoral dissertations |

| 45 | Kinney (2022) USA [70] | QE | 203 E: 111; C: 92 Dropout rate (59.60%) E: −59; C: −62 | Mindful Breathing | No intervention | JSE-HPS (empathy) | No statistically significant difference | Doctoral dissertations |

| 46 | Klich (2019) USA [71] | QE | 15 −6 (40%) | Mindfulness Meditation Book and the CD by Sharon Salzberg | - | IRI (Empathy); MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); STAI (Anxiety) | An improvement of the investigated outcomes | Doctoral dissertations |

| 47 | Leggett (2010) USA [72] | RCT | 90 E and C not specified Dropout rate −5 (6%) E: 42; C: 43 | Mindfulness Meditation | Usual treatment | CESD-R (Depression) MAAS (Dispositional Mindfulness); Student Clinical Completion Appraisal form (self-efficacy) Clinical Skills Evaluation (Clinical Skills performance) Physiological Measures: (Heart Rate; Blood Pressure) | Statistically significant decrease in depression scores and blood pressure. Statistically insignificant Improvements in mindfulness, self-efficacy, and clinical skills performance. No change for Heart Rate. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 48 | Lynch (2023) USA [73] | QE | 122 Dropout rate −68 (56%) | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | - | Survey (Stress, Resilience) | Students found the website easily accessible and useful. Students’ satisfaction is highlighted | Doctoral dissertations |

| 49 | Medari (2023) USA [74] | MM | 102 Dropout rate −88 (86%) | MindShift® CBT App from device | PSS (Stress); GSES (Self-efficacy) | QN: Not statistically significant differences. QL: Students suggest continuing to use it. | Doctoral dissertations | |

| 50 | Oseguera (2019) USA [75] | MM | 175 Dropout rate −100 (57%) QN: 60; QL: 15 | Mindfulness Meditation | - | PSS (Stress); CAM-R (Dispositional mindfulness); Inquiry (Mindfulness experience) | QN: Statistically significant improvement on stress and awareness. QL: positive experience | Doctoral dissertations |

| 51 | Ross (2022) USA [76] | QE | 79 Dropout rate −50 (63%) | Adapted MBSR | - | SOS-S and PSS (Stress) Survey (students’ perception) | No statistically significant difference Increased sense of calm and engaged | Doctoral dissertations |

| 52 | Simonton (2021) USA [77] | MM | 57 Dropout rate −41 (72%) | Koru Mindfulness Meditation Online | - | STAI (Anxiety); Inquiry (Students’ experience; mindfulness strategies used) | QN data are scarce; QL: MBIs benefited the students in personal and professional life. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 53 | Tenrreiro (2022) USA [78] | QE | 20 Dropout rate Not specified | MBSR | - | CTAS-2 (Anxiety) | An improvement of the investigated outcome | Doctoral dissertations |

| 54 | Teribury (2021) USA [79] | QE | 26 Dropout rate −3 (12%) | Mindfulness Meditation | - | CTAS-2 (Anxiety) | An improvement of the investigated outcome but a negative linear relationship was observed with post-test CTAS-2 scores and mindfulness meditation performance for 200–1400 min. | Doctoral dissertations |

| 55 | Tung (2019) China [80] | RCT | 88 E: 44 C: 44 Dropout rate (17.04%) E: −11; C: −4 | Mindful Self Compassion (MSC) programme | Wait list | Chinese form: FFMQ (Awareness); SCS (Self-Compassion); ProQOL-5 (Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue); PSS (Stress). | An improvement of the investigated outcome | Doctoral dissertations |

| No. | First Author (Year) | MBIs | MBIs Duration | Mode of Delivery | Link Website/App | Adverse Events | Facilitator/Competence | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Niessen (2015) [19] | Mindfulness training | Four-week | In presence | - | Not specified | Not specified | 1st Academic Year |

| 2 | Beddoe (2004) [27] | MBSR in presence and audio guide recorded at home | eight weeks with one session per week of two hours in presence and a commitment of 30 min at home (listening to audio recording) | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | Not specified | Not specified | Ad hoc workshop and home with recorded audio tracks |

| 3 | Bultas (2021) [28] | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | Twenty minutes before the exam for 5 exams | Online | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yxgFAW7wTc (accessed on 22 November 2025) | No adverse events reported | The authors did not have skills as facilitators and for this reason they used YouTube. Not specified the skills of the video’s author. | Online before exams |

| 4 | Burner (2023) [29] | Mindfulness Meditation and MBSR | Sessions took place weekly or every other week, depending on the weeks in which the skills workshops were scheduled. The sessions lasted from 10 to 30 min depending on the time available in the skills lab programme | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | No adverse events reported | The first female researcher. Self-paced online courses. MBSR practitioner. Specialized in Mental Health Nursing | Before the nursing skills workshop session |

| 5 | Chiam (2020) [30] | Mind-Nurse Program | Eight sessions of one hour and half and 10–20 min practice at home | In presence | - | “I have not received any reports of side effects. Some students felt asleep during the mindfulness practice during the session.” (Au) | Last author of the article. Mindfulness facilitator experiences. Specialization in Mental Health Nursing. Formal training (with certificate) on the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programme in Singapore. Continuing informal training (monthly training) from a meditation practitioner in Thailand. | Ad hoc workshop and home practice |

| 6 | Kou (2022) [31] | MBSR MBCT | Two hours per session, one session per week for eight weeks | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | No adverse events reported | The Researcher. Experienced mindfulness facilitator (>5 years) who has incorporated the principles of the Unified Mindfulness system into the training | Extracurricular course in presence and at home |

| 7 | Lam (2024) [32] | Mindfulness-based PAL | Five-forty minutes for eight weeks; (from nine to 16 weeks) | Online workshops and audio guides at home | - | No adverse events reported | Research Assistant and Peer Leader. The Research Assistant Trainer is a qualified mindfulness instructor who has extensive experience in providing mindfulness training to healthcare professionals. | Extracurricular peer to peer online course |

| 8 | Pollard (2020) [33] | Mindfulness moment before clinical simulation | Two minutes before the three-hour, five-match simulation | In presence | - | No adverse events reported | Course Facilitators. Script preparations and facilitator training by a mindfulness expert, Dr. Shelley Winton of Alberta Health Services | Before participating in the gestural simulation workshops |

| 9 | Schwarze (2015) [34] | MBCT Recorded guide on Podcast | Six one-hour sessions | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | Maddux and Maddux podcast (2006) https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/meditation-oasis/id204570355?mt=2 (accessed on 22 November 2025) | No adverse events reported | Podcast authors are Mindfulness Meditation experts. Licensed Professional Counselor Trainer | Spring Semester |

| 10 | Uysal (2022) [35] | MBSR | Two hours two days a week for four weeks | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | “One student said that his mindfulness practice had increased his awareness, but that his stress level had also increased. He described himself as a person with a lot of anxiety and stress. However, he remained in the intervention group” (Au) | Researcher. Trained in the MBSR | Extra-Curricular Course |

| 11 | Chen (2013) [36] | Mindful breathing | 30 min a day for seven consecutive days | In presence | - | Not specified | Senior Consultant Psychologist, Expert in the practice of Mindfulness meditation techniques | Ad hoc workshop |

| 12 | Kang (2019) [37] | Stress Coping Program MBIs | Ninety minutes per session for eight weeks (one session per week) | In presence | - | Not specified | The researcher. Professional training in mindfulness meditation with eight years of conducting experience. | Ad hoc workshop during the internship |

| 13 | Song (2015) [38] | MBSR | Two hours a week for eight weeks | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | Not specified | Mindfulness Instructor. Over 10 years of experience in MSR | Extra-Curricular Course |

| 14 | Alhawatmeh (2022) [39] | Meditation “of the sense” ABC Relaxation Theory protocol | Three hours of plenary to explain the study. Five weekly sessions of 30 min of mindfulness meditation | In presence | - | Not specified | Not specified | Ad hoc workshop |

| 15 | Alsaraireh (2017) [40] | Mindfulness Meditation | 1 h for 3 days a week for 10 weeks | In presence | - | Not specified | Not specified | Ad hoc workshop |

| 16 | Burger (2017) [41] | Mindfulness Meditation online and recording | Ten minutes a day for 4 weeks | Online University of Wisconsin Podcast-Department of Public Health | https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/mindfulness-meditation-podcast-series/ (accessed on 30 October 2024) | Not specified | Senior Researcher, that trained as a mindfulness facilitator and daily practice | Online at home in the first half of the year |

| 17 | Can Gür (2020) [42] | MBET | Eight weeks: one hour twice a week for a total of 16 meetings | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | Not specified | Significant increase in the level of empathy in the Experimental group. No significant change in total age discrimination scores was recorded in either group | Ad hoc workshop |

| 18 | Chase-Cantarini (2019) [43] | Mindfulness moments | Five-ten minutes before the theory lesson every week of a semester | in presence before the lesson | Not specified | The authors: nurse educators without specific training | Before the theoretical lessons | |

| 19 | Cheli (2020) [44] | MBEP (SANP) | Six-weeks MBEP: Five regular sessions of three hours and one session of four hour and half | In presence | - | Not specified | Specific training and supervision, at least 2 years of experience as a Mindfulness teacher | Replacement of a pre-existing course in General Pedagogy. MBIs has been delivered in conjunction with the final internship |

| 20 | Colburn (2023) [45] | Mindful Self-Compassion Workshop with sandtray | Four-hour workshop | In presence | - | Not specified | The researcher. A Certificate of Advanced Practice in Mind–Body Medicine | Workshop part of the curriculum of nursing students |

| 21 | Dai (2022) [46] | MLWC | Variable for intervention; 30–40 min per lesson (two lessons per session) for six weeks | Online | - | Not specified | Two psychiatrists. Certified Mindfulness Facilitator at Mindfulness Awareness Research Center California | Extracurricular course |

| 22 | Ebrahem (2022) [47] | Mindfulness Practices | Not specified | Not specified | - | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 23 | ElKayal (2022) [48] | Theoretical session and Mindfulness Practices | Forty-five/sixty minutes per session for a total of eight sessions in three months | In presence | - | Not specified | Researchers. Certificated in mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques (MBSR) at the Zagazig University Psychiatric Center. | Ad hoc workshop |

| 24 | Franco (2022) [49] | TAO Bookstore: Mindfulness Practices | Twelve mindfulness exercises lasting from two to eleven minutes for a total of four weeks | Online | https://www.taoconnect.org/ (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | Course Facilitator (Interactive Site). Therapy Assistance Online (TAO) is a peer-reviewed interactive website developed by Dr. Susan Benton in 2012 | During a semester |

| 25 | Hutchison (2016) [50] | Mindfulness in Learning Disability Practice Workshop | Nine hours in two days | In presence | - | “College nursing programs need to consider how the application of mindfulness can create emotional dependency in students.” (Au) | Psychologist. Lecturer trained at a seminar on leadership development Decide, Commit, Proceed. | Ad hoc workshop |

| 26 | Karaca (2019) [51] | MBSR | Ninety/Ninety-five minutes twice a week for a total of 12 weeks | In presence with a request for 10 min a day at home | - | Not specified | Researcher, that was a cognitive and behavioural therapist. European Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies Accreditation Certificate. | MBSR has been included in the Coping course programme during the autumn semester |

| 27 | Ksiksou (2022) [52] | MBSR | Sessions of 2.30 h per week with a minimum of 20 min of home practice for a total of eight weeks | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | Not specified | Psychiatrist Expert in MBSR. MBSR Specialization | Extracurricular course in presence and at home | |

| 28 | Munif (2019) [53] | Islamic spiritual mindfulness | Twenty-five minutes for five days at home: morning, afternoon and evening. | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 29 | Öztürk (2023) [54] | Adapted MBSR | Ninety minutes twice a week. Four-hour retreat and not eight hours. | Online | - | Not specified | The researcher. Certified Cognitive-Behavioural Therapist, Mindfulness and Acceptance Engagement Professional | Extra-Curricular Course |

| 30 | Quatraro (2024) [55] | Mindfulness exercise Pre-recorded audio files | Six weeks for three/four days a week for five/seven minutes | Online through mobile App Smiling Mind | https://www.smilingmind.com.au (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | Not specified | 3rd and 4th year students |

| 31 | Ratanasiripong (2015) [56] | Vipassana Meditation | Three times a day for four weeks. Not specified time for each session | In presence | - | Not specified | Meditation instructor. Not specified certificate | Before the clinical internship |

| 32 | Sari Ozturk (2022) [57] | Mindfulness-based mandalas | Three one-hour meetings for three weeks, one meeting per week. | Online | - | Not specified | Researcher. Mindfulness-based mandala drawing certificate and a therapeutic art life coach certificate | During the clinical internship in the COVID period |

| 33 | Scheick (2011) [58] | STEDFAST S-AM | Three minutes of breathing before the meetings. Not specified the number of meetings | In presence | - | Not specified | Not specified | Two semesters for community psychiatric and mental health nursing |

| 34 | Spadaro (2016) [59] | MBSR | One day a week for eight weeks. Not specified the time for each session | Online | - | Not specified | Not specified | During a semester (not the last) |

| 35 | Tarhan (2023) [60] | Short form MBSR | One hour per week for four weeks | In presence | - | Not specified | Second author. Trained in MBSR | Ad hoc workshop |

| 36 | Torné-Ruiz (2023) [61] | 10-daymindfulness | Twenty-five minutes in 10 days | Online | https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLokeFpXsus96XL_E2rgQTnd9YxFPlwzix (accessed on 22 November 2025) https://www.cc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/internet-files/palliativecare/pdf/MindfulnessManual.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024) | Not specified | Mindfulness instructor. Awareness expert with experience in conducting courses and training | Before the clinical simulations |

| 37 | Yüksel (2020) [62] | MBCT | Two hours a week for eight weeks | In presence | - | Not specified | The first researcher. Training and supervision on cognitive and behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction | Extra-Curricular Course |

| 38 | Arthur (2022) [63] | A record on Mindful Breathing | 3 min before theory classes until exam day | A recording on Mindful Breathing listened in presence | - | Not specified | Researcher unrelated to the degree course. Competence not specified | before the theoretical lessons |

| 39 | Baich (2022) [64] | Mindfulness guide with smartphone | 12 days in 5 weeks (for a total of 75 min with an average per session of 6.32 min) | Online through mobile App “Smiling mind” | https://www.smilingmind.com.au (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | Not specified | Online, before theoretical lessons |

| 40 | Bonfe (2023) [65] | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | five minutes before the exam for six exams | Online before the exam through the semester | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yxgFAW7wTc (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | The researcher who implemented the project. He completed a 20 min basic training in mindfulness. The training included motivation and guide to exercise of awareness. | Introduced during the pharmacology course. Before the exams of the whole semester |

| 41 | Davis (2020) [66] | Koru Mindfulness Meditation | Seventy-five minutes per session; one session per week for four weeks | Online | - | Not specified | Psychiatrist and Koru Mindfulness Meditation instructor. Expert Certificate | Extra-Curricular Course |

| 42 | Dodson (2021) [67] | MBSR: Burdick’s Workbook | Every week in class before class for 15–20 min before the placement test | In presence | - | Not specified | Expert-trained teachers. Three weeks in the first half according to the Burdick protocol (2013) | Before the classroom lesson until the final test (1st semester) |

| 43 | Foster (2017) [68] | Theoretical session and Mindfulness Practices | one hour session for eight sessions | In presence with Supplementary Materials for home practice | - | Not specified | Mindfulness Facilitator. Formal training in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) from the Oasis Institute (University of Massachusetts, 2014), which is part of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare, and Society (CMMHCS) | Ad hoc workshop before the internship experience |

| 44 | Heinrich (2022) [69] | Listening to 10 min of Meditation recording | Ten minutes of Meditation recording three days a week for four weeks | Audio resources | - | Not specified | Recorded Meditation. Not specified author’s competences. | Not specified |

| 45 | Kinney (2022) [70] | Mindful Breathing | One minute and 30 s | Online | Dr. Andrew Weil, (breathing 4-7-8) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRPh_GaiL8s (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | The host of the video is Dr. Andrew Weil. Dr. Andrew Weil is a holistic physician | Before and after the theoretical lessons |

| 46 | Klich (2019) [71] | Mindfulness Meditation Book and the CD by Sharon Salzberg | Fifteen minutes a day of meditation and 30 min a week of reading for four weeks | At home with Supplementary Materials for practice (Book and the CD by Sharon Salzberg) | - | “No adverse events occurred. Recruits were briefed on potential risks and provided with contact information for mental health services as a precaution.” (Au) | Book and cd by Sharon Salzberg’s Real Happiness: The Power of Meditation: A 28-Day Program book and audio CD. Sharon Salzberg is a meditation teacher | Extracurricular at home |

| 47 | Leggett (2010) [72] | Mindfulness Meditation | A session of one hour and half per week for three weeks | In presence with daily practice of 20 min at home | - | Not specified | Experienced Mindful Breathing Facilitator | Ad hoc workshops |

| 48 | Lynch (2023) [73] | Short Mindfulness Meditation exercise online | Not specified | Online | - | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 49 | Medari (2023) [74] | MindShift® CBT App from device | Ten minutes five times a week for six weeks | Online through mobile App MindShift® CBT | https://www.youtube.com/embed/0Ka10cf9dSY?feature=oembed (accessed on 30 October 2024) | Not specified | Not specified | Academic Semester |

| 50 | Oseguera (2019) [75] | Mindfulness Meditation | Five minutes a day for four weeks | In presence with online video | - | Not specified | The teachers. Not specified competences. | In the first five minutes of the theory lesson |

| 51 | Ross (2022) [76] | Adapted MBSR | Fifteen minutes sessions before the start of the theoretical course (7:35 am to 7:50 am; lesson start time 8:00 am) one session per week | In presence with daily practice of 10–30 min at home | - | Not specified | The first researcher under the supervision of the course teacher who had an interest in Mindfulness Meditation | During the first semester before the begin of the course |

| 52 | Simonton (2021) [77] | Koru Mindfulness Meditation Online | Five-ten minutes of MK per day for five weeks | Online | - | Not specified | Not specified | Before High-Fidelity Simulations |

| 53 | Tenrreiro (2022) [78] | MBSR | Not specified | Not specified | - | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 54 | Teribury (2021) [79] | Mindfulness Meditation | Eight weeks. Not specified the time of each connection to the App | Online through mobile App Headspace | https://www.headspace.com/headspace-meditation-app (accessed on 22 November 2025) | Not specified | Not specified | During a semester |

| 55 | Tung (2019) [80] | Mindful Self Compassion (MSC) programme | Eight weeks with one session per week lasting three hours and a half-day retreat scheduled between the fourth and fifth sessions | In presence | - | Not specified | MSC Certified Teacher | Not specified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Consorte, M.; Morotti, E.; Nanni, F.; Giannandrea, A.; Benini, S.; Martoni, M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Implement the Psychological Well-Being of Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010130

Consorte M, Morotti E, Nanni F, Giannandrea A, Benini S, Martoni M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Implement the Psychological Well-Being of Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleConsorte, Milena, Elena Morotti, Fabio Nanni, Alessandro Giannandrea, Stefano Benini, and Monica Martoni. 2026. "Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Implement the Psychological Well-Being of Nursing Students: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010130

APA StyleConsorte, M., Morotti, E., Nanni, F., Giannandrea, A., Benini, S., & Martoni, M. (2026). Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Implement the Psychological Well-Being of Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 14(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010130