Medical Service Utilization for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Korea (2010–2017): A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nationally Representative Sample from the HIRA-National Patient Sample Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

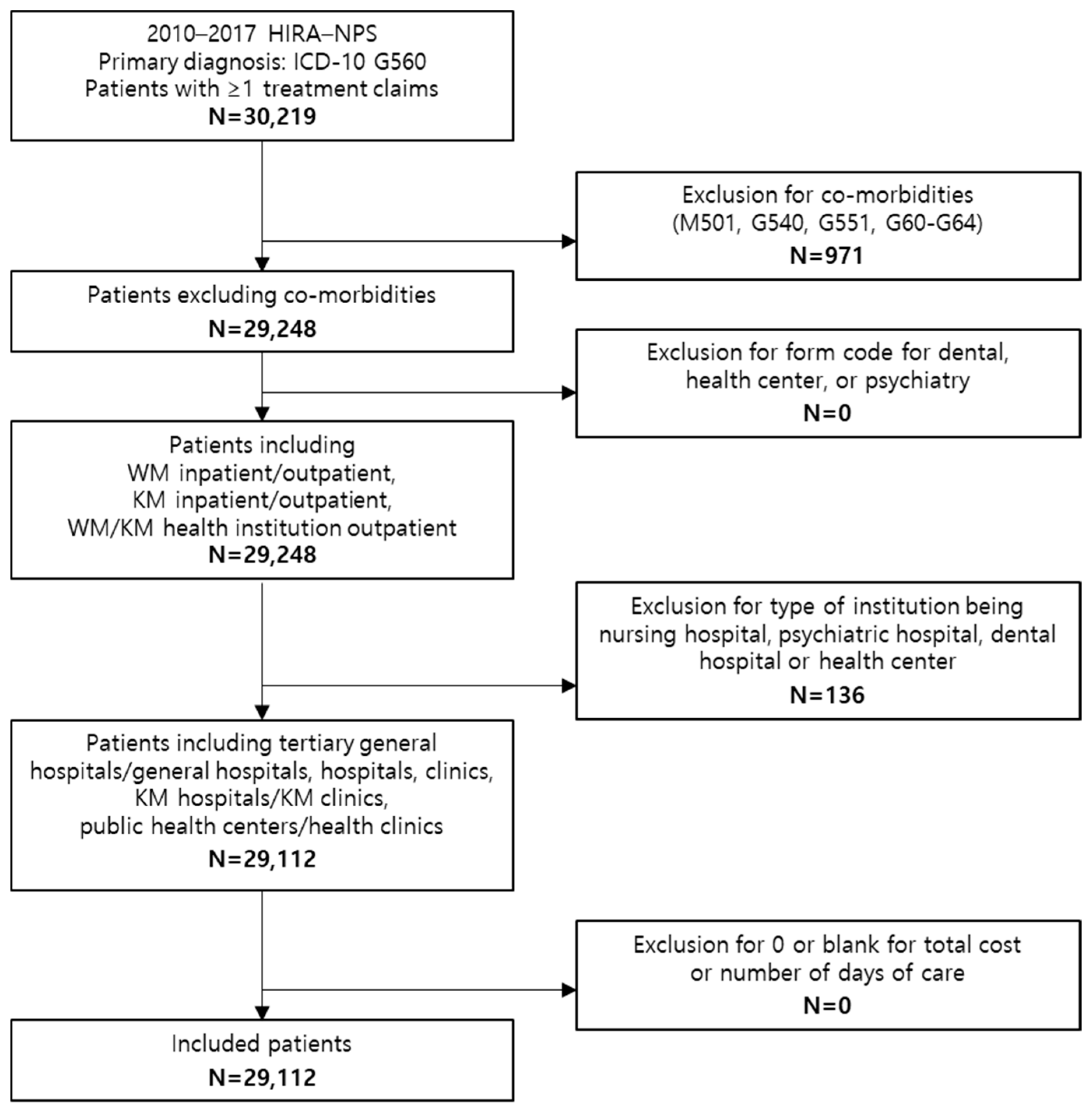

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Cost Standardization

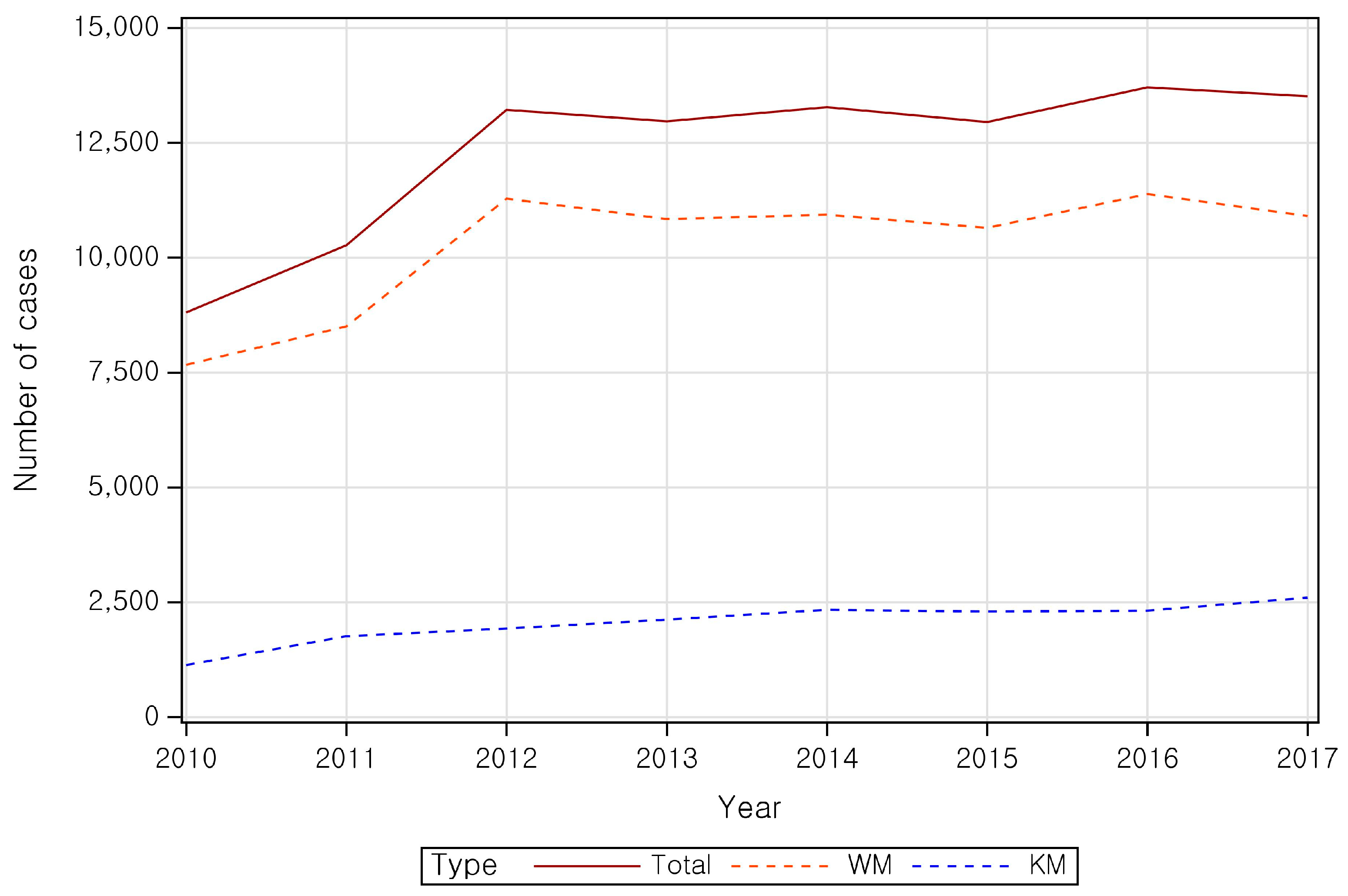

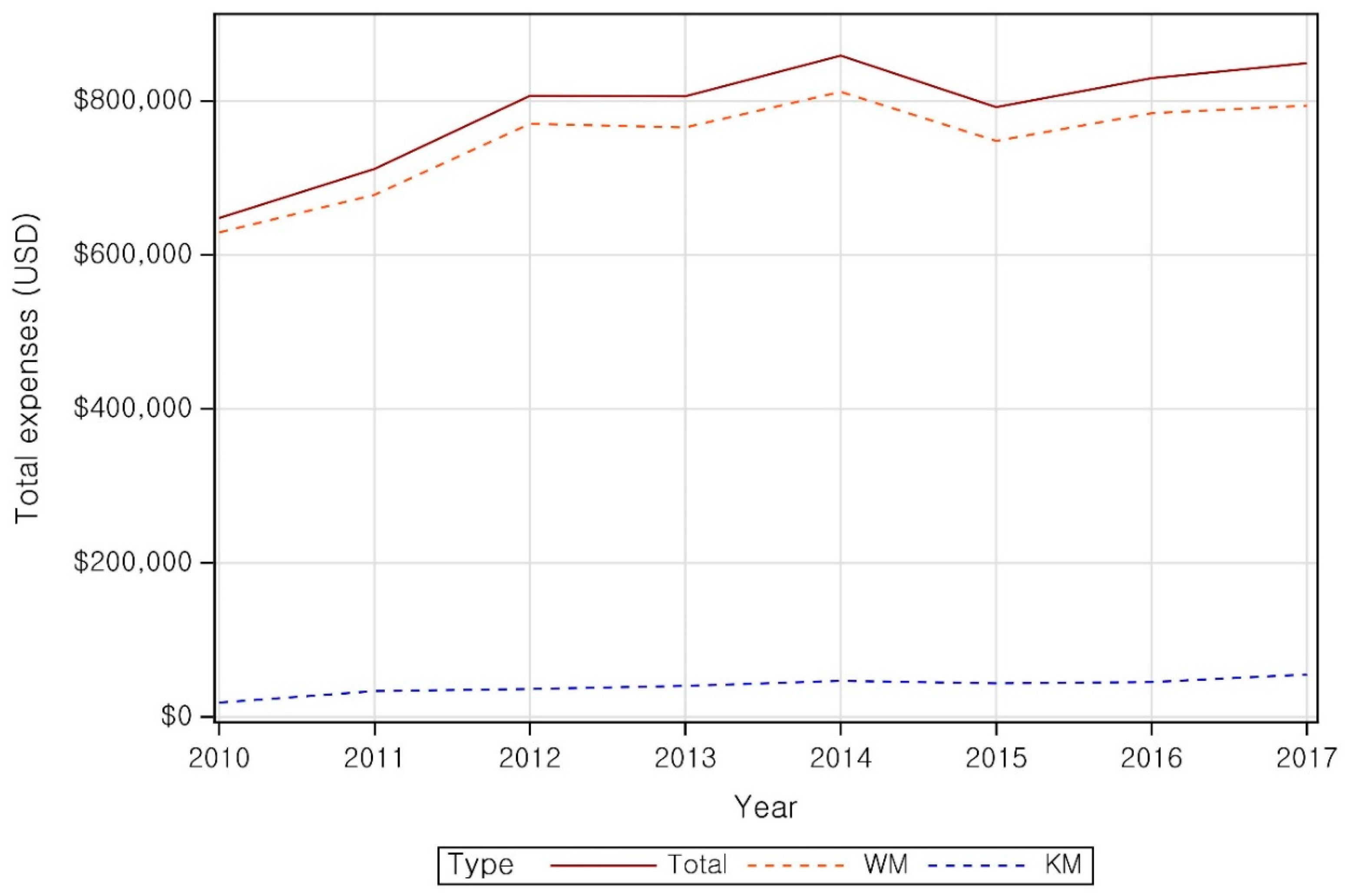

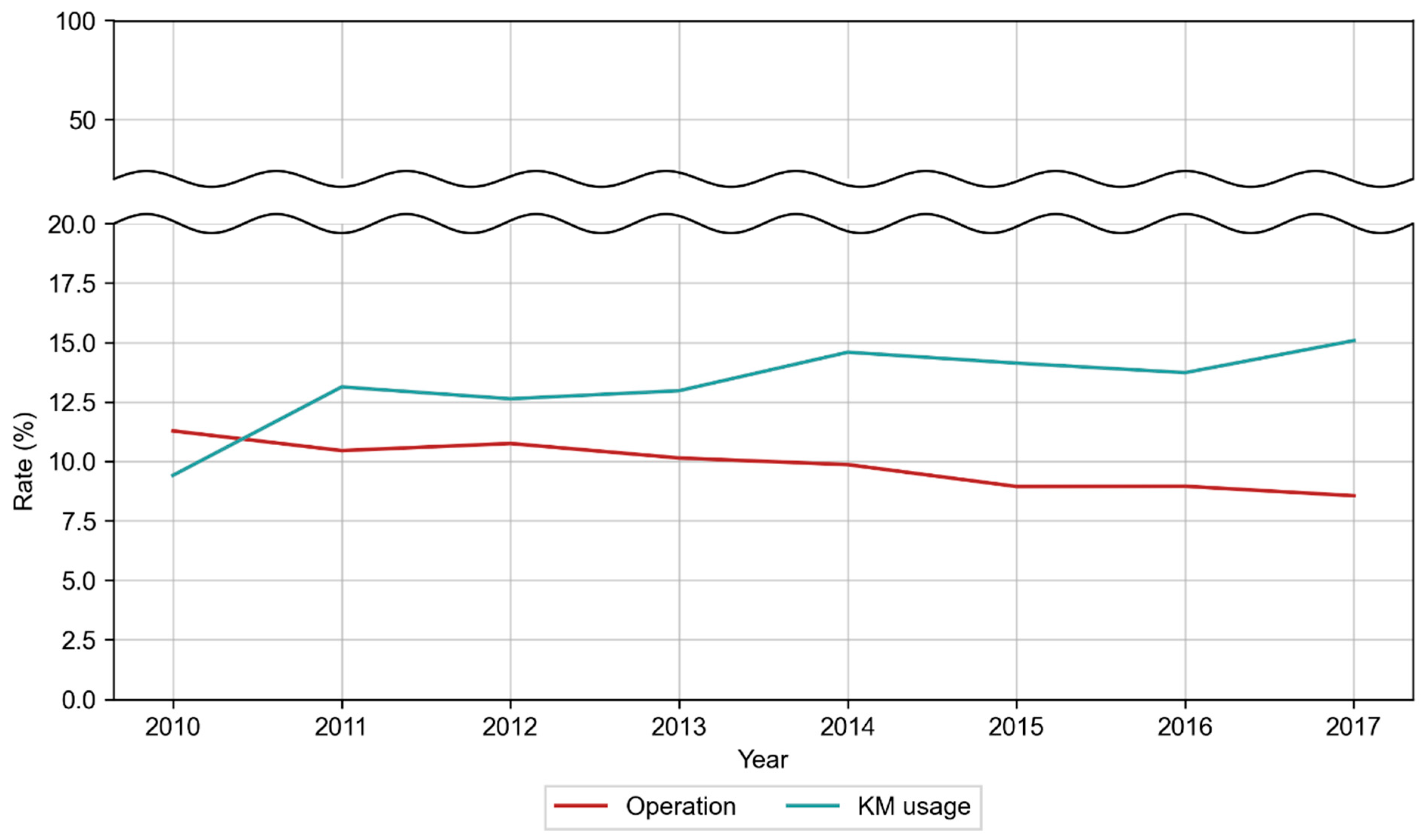

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korean Rehabilitation Society. TSoKM: Korean Rehabilitation Medicine, 5th ed.; Globooks: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, C.; Chesterton, L.S.; Davenport, G. Diagnosing and managing carpal tunnel syndrome in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, H.S. Validation of known risk factors associated with carpal tunnel syndrome: A retrospective nationwide 11-year population-based cohort study in South Korea. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammas, M.; Boretto, J.; Burmann, L.M.; Ramos, R.M.; dos Santos Neto, F.C.; Silva, J.B. Carpal tunnel syndrome-Part I (anatomy, physiology, etiology and diagnosis). Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2014, 49, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckhaupt, S.E.; Dahlhamer, J.M.; Ward, B.W.; Sweeney, M.H.; Sestito, J.P.; Calvert, G.M. Prevalence and work-relatedness of carpal tunnel syndrome in the working population, United States, 2010 national health interview survey. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.; Hanrahan, L. Social and economic costs of carpal tunnel surgery. Instr. Course Lect. 1995, 44, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wipperman, J.; Goerl, K. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2016, 94, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Blazar, P.; Earp, B.E. Rates of complications and secondary surgeries of mini-open carpal tunnel release. HAND 2019, 14, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadianfard, M.; Bazrafshan, E.; Momeninejad, H.; Jahani, N. Efficacies of acupuncture and anti-inflammatory treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2015, 8, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-P.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Wang, N.-H.; Li, T.-C.; Hwang, K.-L.; Yu, S.-C.; Chang, M.-H. Acupuncture in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, M.G.; Kinaci, A.; Ju, K.; Guitton, T.G.; Mudgal, C.S.; Ring, D.; Abzug, J.M.; Adams, J.; Arbelaez, G.F.; Aspard, T. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Assessment of surgeon and patient preferences and priorities for decision-making. J. Hand Surg. 2014, 39, 1799–1804.e1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.L.; Chen, Y.; Chesterton, L.S.; Van Der Windt, D.A. Trends in the prevalence, incidence and surgical management of carpal tunnel syndrome between 1993 and 2013: An observational analysis of UK primary care records. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Park, H.-J.; Kim, H.-T.; Park, S.-Y.; Heo, I.; Hwang, M.-S.; Shin, B.-C.; Hwang, E.-H. Clinical practice patterns for carpal tunnel syndrome in Korean medicine: An online survey. J. Churna Man. Med. Spine Nerves 2021, 16, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y.H.; Chung, M.S.; Baek, G.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Rhee, S.H.; Gong, H.S. Incidence of clinically diagnosed and surgically treated carpal tunnel syndrome in Korea. J. Hand Surg. 2010, 35, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, C.; Jang, B.-H.; Ko, S.-G. A review of major secondary data resources used for research in traditional Korean medicine. Perspect. Integr. Med. 2023, 2, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Khan, W.; Goddard, N.; Smitham, P. Carpal tunnel syndrome: A review of the recent literature. Open Orthop. J. 2012, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, M.; Giannini, F.; Giacchi, M. Carpal tunnel syndrome incidence in a general population. Neurology 2002, 58, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmemari, M.H.; Heliövaara, M.; Viikari-Juntura, E.; Shiri, R. Carpal tunnel release: Lifetime prevalence, annual incidence, and risk factors. Muscle Nerve 2018, 58, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, Y.; Menuki, K.; Tajima, T.; Okada, Y.; Kosugi, K.; Zenke, Y.; Sakai, A. Effect of estradiol on fibroblasts from postmenopausal idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome patients. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 8723–8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Naseri, M.; Namazi, H.; Ashraf, M.J.; Ashraf, A. Correlation between female sex hormones and electrodiagnostic parameters and clinical function in post-menopausal women with idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Menopausal Med. 2016, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasielska-Trojan, A.; Sitek, A.; Antoszewski, B. Second to fourth digit ratio (2D:4D) in women with carpal tunnel syndrome. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 137, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.-C.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Guo, H.-R. Association between hormone replacement therapy and carpal tunnel syndrome: A nationwide population-based study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rousan, T.; Sparks, J.A.; Pettinger, M.; Chlebowski, R.; Manson, J.E.; Kauntiz, A.M.; Wallace, R. Menopausal hormone therapy and the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in postmenopausal women: Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieslander, G.; Norbäck, D.; Göthe, C.; Juhlin, L. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and exposure to vibration, repetitive wrist movements, and heavy manual work: A case-referent study. Occup. Environ. Med. 1989, 46, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjernbrandt, A.; Vihlborg, P.; Wahlström, V.; Wahlström, J.; Lewis, C. Occupational cold exposure and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome–a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmus, H.; Antoniadis, G. Occupation-related Mononeuropathies in Athletes, Musicians, etc. In Nerve Compression Syndromes: A Practical Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, R.D.; Jones, C.M.C.; Hammert, W.C. Identification of clinical and demographic predictors for treatment modality in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. HAND 2023, 18, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pablo, P.; Katz, J.N. Pharmacotherapy of carpal tunnel syndrome. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2003, 4, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Alsam, M.A.; Hasan, A. Role of Oral Steroids in The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Pak. Armed Forces Med. J. 2022, 72, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Available online: https://www.aaos.org/cts2cpg (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Billig, J.I.; Sears, E.D. Nonsurgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: A survey of hand surgeons. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.–Glob. Open 2022, 10, e4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Bobos, P.; Lalone, E.A.; Warren, L.; MacDermid, J.C. Comparison of the short-term and long-term effects of surgery and nonsurgical intervention in treating carpal tunnel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. HAND 2020, 15, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, P.N.; Westenberg, R.F.; Langer, M.F.; Oflazoglu, K.; van der Heijden, E.P. State of the art review. Complications after carpal tunnel release. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 2024, 49, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayegh, E.T.; Strauch, R.J. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly-Pen, D.; Andreu, J.L.; Millán, I.; de Blas, G.; Sánchez-Olaso, A. Long-Term Outcome of Local Steroid Injections Versus Surgery in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Observational Extension of a Randomized Clinical Trial. HAND 2022, 17, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-S. Acupuncture and endorphins. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 361, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-Q. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008, 85, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Lao, L.; Ren, K.; Berman, B.M. Mechanisms of acupuncture-electroacupuncture on persistent pain. Anesthesiology 2014, 120, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Cleland, J.A.; Pareja, J.A.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Ortega-Santiago, R. Manual therapy versus surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome: 4-year follow-up from a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multanen, J.; Uimonen, M.M.; Repo, J.P.; Häkkinen, A.; Ylinen, J. Use of conservative therapy before and after surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Patient | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (2010–2017) | WM (2010–2017) | KM (2010–2017) | WM + KM (2010–2017) | ||||||

| Total N | Percent | Total N | Percent | Total N | Percent | Total N | Percent | ||

| 29,058 | 100.00 | 25,176 | 100.00 | 2975 | 100.00 | 907 | 100.00 | ||

| Sex | Male | 6310 | 21.72 | 5462 | 21.70 | 699 | 23.50 | 149 | 16.43 |

| Female | 22,748 | 78.28 | 19,714 | 78.30 | 2276 | 76.50 | 758 | 83.57 | |

| Age | ≤19 | 193 | 0.66 | 168 | 0.67 | 25 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 20–29 | 1074 | 3.7 | 903 | 3.59 | 154 | 5.18 | 17 | 1.87 | |

| 30–39 | 2546 | 8.76 | 2141 | 8.50 | 339 | 11.39 | 66 | 7.28 | |

| 40–49 | 6194 | 21.32 | 5374 | 21.35 | 616 | 20.71 | 204 | 22.49 | |

| 50–59 | 11,222 | 38.62 | 9832 | 39.05 | 990 | 33.28 | 400 | 44.10 | |

| 60–69 | 5073 | 17.46 | 4380 | 17.40 | 542 | 18.22 | 151 | 16.65 | |

| ≥70 | 2756 | 9.48 | 2378 | 9.45 | 309 | 10.39 | 69 | 7.61 | |

| Payer type | NHI | 27,688 | 95.29 | 23,926 | 95.03 | 2884 | 96.94 | 878 | 96.80 |

| Medicaid | 1363 | 4.69 | 1243 | 4.94 | 91 | 3.06 | 29 | 3.20 | |

| Others * | 7 | 0.02 | 7 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Category | Claims | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (2010–2017) | WM (2010–2017) | KM (2010–2017) | |||||

| Total N | Percent | Total N | Percent | Total N | Percent | ||

| 98,737 | 100.00 | 82,200 | 100.00 | 16,537 | 100.00 | ||

| Type of visit | Outpatient | 95,858 | 97.08 | 79,329 | 96.51 | 16,529 | 99.95 |

| Inpatient | 2879 | 2.92 | 2871 | 3.49 | 8 | 0.05 | |

| Medical institution | Tertiary hospital/ general hospital/hospital | 32,246 | 32.66 | 32,212 | 39.19 | 34 | 0.21 |

| Clinic | 49,941 | 50.58 | 49,941 | 60.76 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| KM hospital | 516 | 0.52 | 31 | 0.04 | 485 | 2.93 | |

| KM clinic | 16,015 | 16.22 | 0 | 0.00 | 16,015 | 96.84 | |

| Public health center/health clinic | 19 | 0.02 | 16 | 0.02 | 3 | 0.02 | |

| Total | WM | KM | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Case | % | Case per Patient | Cost | % | Cost per Patient | Case | % | Case per Patient | Cost | % | Cost per Patient | Case | % | Case per Patient | Cost | % | Cost per Patient |

| Examination fee | 12,215 | 4.49 | 0.42 | $1,372,330 | 21.55 | $47 | 12,215 | 5.15 | 0.47 | $1,372,330 | 22.70 | $53 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Anesthesia fee | 15,776 | 5.80 | 0.54 | $571,934 | 8.98 | $20 | 15,688 | 6.61 | 0.60 | $571,559 | 9.45 | $22 | 88 | 0.25 | 0.02 | $375 | 0.12 | $0 |

| Non-benefit services/others | 1221 | 0.45 | 0.04 | $29,872 | 0.47 | $1 | 1221 | 0.51 | 0.05 | $29,872 | 0.49 | $1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Imaging diagnosis and radiology | 11,538 | 4.24 | 0.40 | $246,482 | 3.87 | $8 | 11,538 | 4.86 | 0.44 | $246,482 | 4.08 | $9 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Outpatient medication costs | 41,731 | 15.34 | 1.44 | $541,409 | 8.50 | $19 | 41,731 | 17.59 | 1.60 | $541,409 | 8.96 | $21 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Physical therapy fee | 27,503 | 10.11 | 0.95 | $182,925 | 2.87 | $6 | 27,503 | 11.59 | 1.05 | $182,925 | 3.03 | $7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Admission fee | 2859 | 1.05 | 0.10 | $688,363 | 10.81 | $24 | 2854 | 1.20 | 0.11 | $685,713 | 11.34 | $26 | 5 | 0.01 | 0.00 | $2650 | 0.82 | $1 |

| Fee for psychotherapy | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00 | $212 | 0.00 | $0 | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00 | $212 | 0.00 | $0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Injection fee | 40,957 | 15.06 | 1.41 | $587,408 | 9.22 | $20 | 24,446 | 10.30 | 0.94 | $396,612 | 6.56 | $15 | 16,511 | 47.58 | 4.25 | $190,796 | 59.14 | $49 |

| Consultation fee | 97,862 | 35.98 | 3.37 | $1,049,983 | 16.49 | $36 | 81,338 | 34.28 | 3.12 | $924,363 | 15.29 | $35 | 16,524 | 47.62 | 4.26 | $125,620 | 38.94 | $32 |

| Procedure and surgery | 11,446 | 4.21 | 0.39 | $1,000,951 | 15.72 | $34 | 11,446 | 4.82 | 0.44 | $1,000,951 | 16.56 | $38 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Medication administration and prescription filling fee | 8862 | 3.26 | 0.3 | $96,523 | 1.52 | $3 | 7287 | 3.07 | 0.28 | $93,363 | 1.54 | $4 | 1575 | 4.54 | 0.41 | $3160 | 0.98 | $1 |

| All | 271,979 | 100 | 9.36 | $6,368,393 | 100 | $219 | 237,276 | 100.00 | 9.10 | $6,045,792 | 100.00 | $232 | 34,703 | 100.00 | 8.94 | $322,601 | 100.00 | $83 |

| Items | Number of Patients N (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Nerve condition study | 765 (25.99%) | 822 (25.34%) | 947 (25.50%) | 905 (24.01%) | 856 (22.75%) | 803 (21.48%) | 825 (20.68%) | 838 (21.20%) |

| Electromyography | 519 (17.64%) | 570 (17.57%) | 704 (18.96%) | 651 (17.27%) | 618 (16.43%) | 585 (15.65%) | 588 (14.74%) | 585 (14.80%) |

| Manual muscle test | 24 (0.82%) | 22 (0.68%) | 24 (0.65%) | 28 (0.74%) | 13 (0.35%) | 17 (0.45%) | 13 (0.33%) | 26 (0.66%) |

| Hand function test | 8 (0.27%) | 13 (0.40%) | 9 (0.24%) | 9 (0.24%) | 12 (0.32%) | 7 (0.19%) | 15 (0.38%) | 4 (0.10%) |

| X-ray | 780 (26.50%) | 879 (27.10%) | 1094 (29.46%) | 1054 (27.96%) | 1050 (27.91%) | 1052 (28.14%) | 1186 (29.72%) | 1209 (30.58%) |

| Ultrasound | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.05%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Arthrography | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.05%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| CT | 1 (0.03%) | 3 (0.09%) | 2 (0.05%) | 8 (0.21%) | 6 (0.16%) | 5 (0.13%) | 14 (0.35%) | 5 (0.13%) |

| Bone scan | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 3 (0.08%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) |

| SPECT | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) |

| MRI | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) |

| Raynaud’s scan | 2 (0.07%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alimentary tract and metabolism | 17,277 | 1777 | 1897 | 2222 | 2260 | 2222 | 2183 | 2364 | 2352 |

| 2 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 16,960 | 1749 | 1855 | 2180 | 2210 | 2156 | 2164 | 2325 | 2321 |

| 3 | Nervous system | 12,104 | 1204 | 1300 | 1506 | 1607 | 1527 | 1585 | 1680 | 1695 |

| 4 | Other medications for musculoskeletal system * | 8401 | 854 | 910 | 1060 | 1073 | 1071 | 1033 | 1234 | 1166 |

| 5 | Corticosteroids | 8278 | 737 | 858 | 976 | 1060 | 1092 | 1125 | 1218 | 1212 |

| 6 | Blood and blood forming organs | 7627 | 869 | 903 | 932 | 930 | 940 | 958 | 1058 | 1037 |

| 7 | Muscle relaxants | 6322 | 730 | 754 | 907 | 884 | 765 | 763 | 761 | 758 |

| 8 | Opioids in combination with non-opioid analgesics | 3673 | 210 | 386 | 497 | 507 | 498 | 506 | 541 | 528 |

| 9 | Anti-infectives for systemic use | 3343 | 396 | 384 | 463 | 443 | 429 | 406 | 425 | 397 |

| 10 | Opioids | 2787 | 452 | 313 | 358 | 362 | 347 | 306 | 342 | 307 |

| 11 | Others | 1989 | 231 | 234 | 264 | 257 | 257 | 258 | 243 | 245 |

| 12 | Acetaminophen | 1583 | 182 | 169 | 202 | 196 | 208 | 212 | 201 | 213 |

| 13 | Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 1191 | 147 | 139 | 141 | 161 | 175 | 143 | 133 | 152 |

| 14 | Dermacologicals | 233 | 30 | 34 | 23 | 29 | 30 | 26 | 27 | 34 |

| 15 | Drugs for diabetes | 180 | 18 | 16 | 27 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 20 |

| 16 | Ophthalmologicals | 75 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 19 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 7 |

| 17 | Genito urinary system and sex hormones | 73 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 13 | 14 |

| 18 | Systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins | 30 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.J.; Ha, I.-H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, D. Medical Service Utilization for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Korea (2010–2017): A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nationally Representative Sample from the HIRA-National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare 2026, 14, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010109

Kim JW, Kim SJ, Lee Y-S, Lee YJ, Ha I-H, Kim JY, Kim D. Medical Service Utilization for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Korea (2010–2017): A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nationally Representative Sample from the HIRA-National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ji Won, Soo Jin Kim, Ye-Seul Lee, Yoon Jae Lee, In-Hyuk Ha, Ju Yeon Kim, and Doori Kim. 2026. "Medical Service Utilization for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Korea (2010–2017): A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nationally Representative Sample from the HIRA-National Patient Sample Database" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010109

APA StyleKim, J. W., Kim, S. J., Lee, Y.-S., Lee, Y. J., Ha, I.-H., Kim, J. Y., & Kim, D. (2026). Medical Service Utilization for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Korea (2010–2017): A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nationally Representative Sample from the HIRA-National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare, 14(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010109