Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Swedish National Diabetes Registers Instrument for Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Sampling Strategy

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Study Instrument

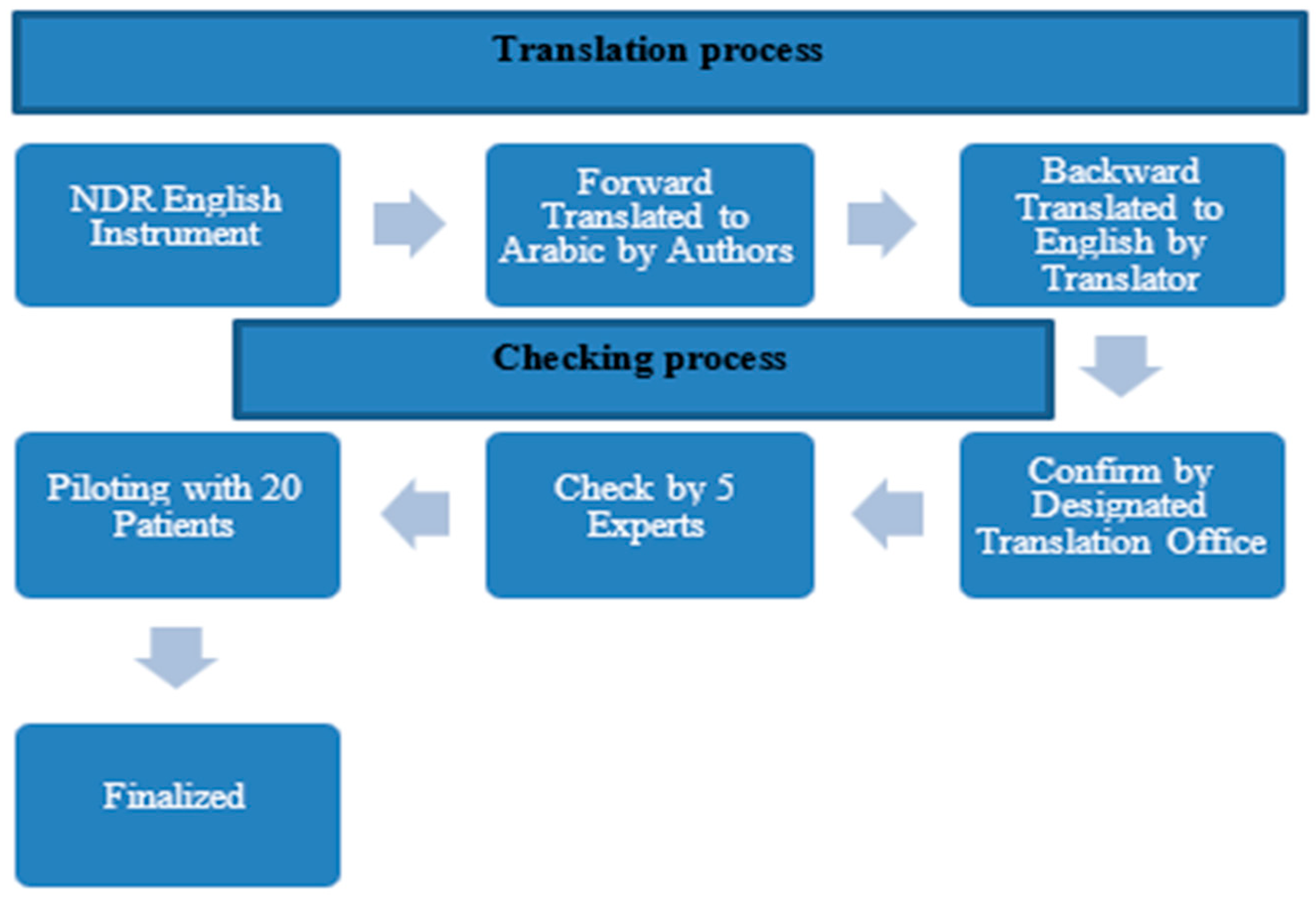

2.5. Translating the Instrument

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participation

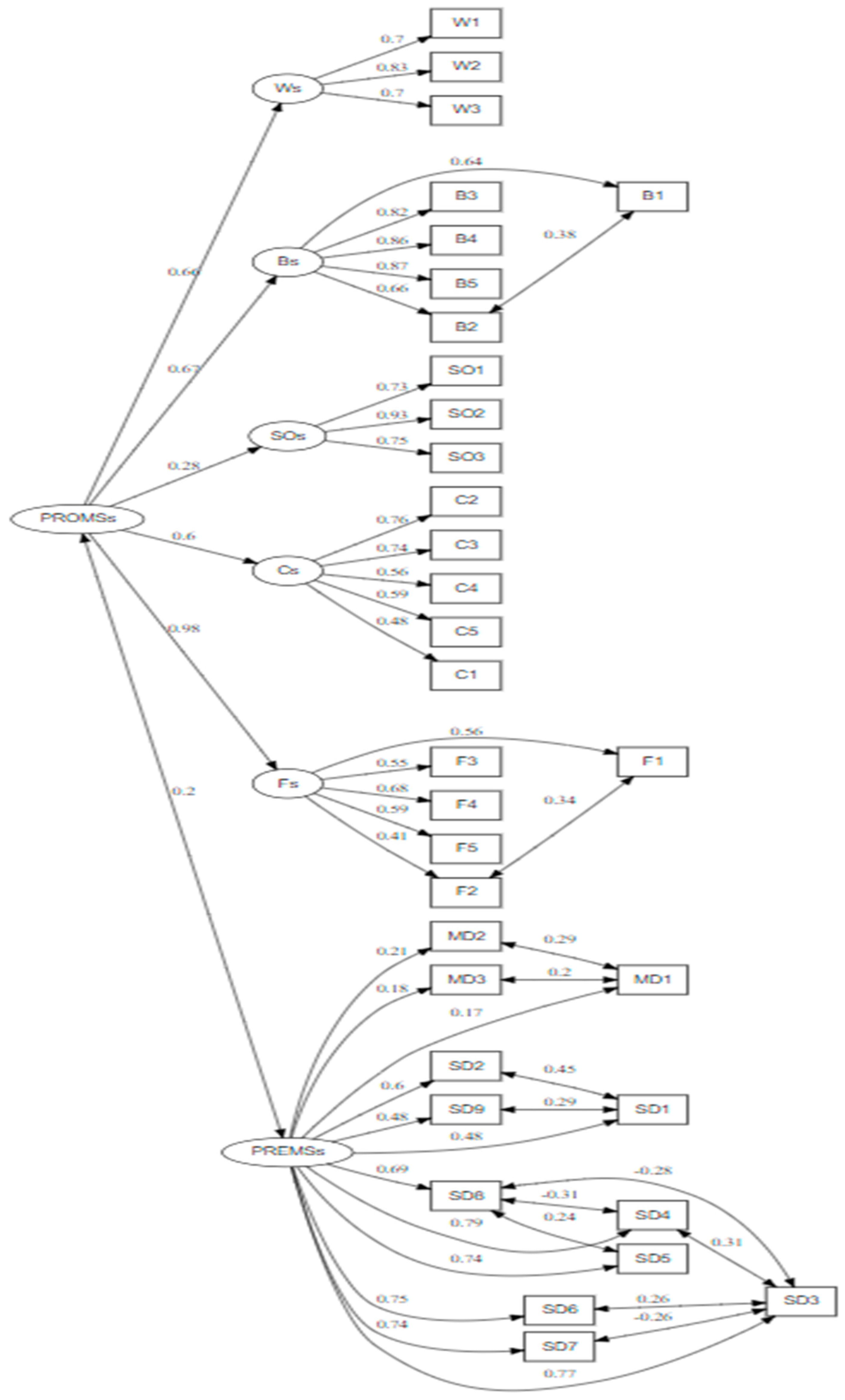

3.2. Contract Validity

3.3. Reliability Analysis

3.4. Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Statement of Principle Findings

4.2. Implication for Policy, Practice, and Research

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PREMs | Patient-Reported Experience Measures |

| SD | Support from Providers |

| MD | Medical Devices |

| PROMs | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| W | Worring |

| F | Feeling |

| B | Barriers |

| C | Capabilities |

| SO | Support from Others |

| VBHC | Value-Based Healthcare |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

References

- Christalle, E.; Zeh, S.; Hahlweg, P.; Kriston, L.; Härter, M.; Scholl, I. Assessment of patient centredness through patient-reported experience measures (ASPIRED): Protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e025896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.-A.R.; Brassil, K.J.; Fujimoto, K.; Fellman, B.M.; Shay, L.A.; Springer, A.E. Exploratory factor analysis of a patient-centered cancer care measure to support improved assessment of patients’ experiences. Value Health 2020, 23, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubahi, N.; Groot, W.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Pavlova, M. Patient-centered care and satisfaction of patients with diabetes: Insights from a survey among patients at primary healthcare centers in Saudi Arabia. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubahi, N.; Pavlova, M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Groot, W. Healthcare Quality from the Perspective of Patients in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, R.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Association of patient experience and the quality of hospital care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2023, 35, mzad047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Larsson, S.; Lee, T.H. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubahi, N.; Pavlova, M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Groot, W. The Association Between Patient-Reported Experience Measures and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Among Patients with Diabetes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Value Health Reg. Issues 2025, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, C.; Teede, H.; Watson, D.; Callander, E.J. Selecting and implementing patient-reported outcome and experience measures to assess health system performance. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e220326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meirte, J.; Hellemans, N.; Anthonissen, M.; Denteneer, L.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Van Daele, U. Benefits and disadvantages of electronic patient-reported outcome measures: Systematic review. JMIR Perioper. Med. 2020, 3, e15588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Abusaib, M.; Ahmed, M.; Nwayyir, H.A.; Alidrisi, H.A.; Al-Abbood, M.; Al-Bayati, A.; Al-Ibrahimi, S.; Al-Kharasani, A.; Al-Rubaye, H.; Mahwi, T.; et al. Iraqi experts consensus on the management of type 2 diabetes/prediabetes in adults. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2020, 13, 1179551420942232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Diabetes Foundation. To Improve Access to Diabetes Care and Prevention Across Northern Region of the West Bank Within the Framework of Palestine MoH National NCD Action Plan. 2022. Available online: https://www.worlddiabetesfoundation.org/what-we-do/projects/wdf15-1304/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. Syrian Diabetes Association. 2022. Available online: https://idf.org/our-network/regions-and-members/middle-east-and-north-africa/members/syria/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Ahmadieh, H.; Itani, H.; Itani, S.; Sidani, K.; Kassem, M.; Farhat, K.; Jbeily, M.; Itani, A. Diabetes and depression in Lebanon and association with glycemic control: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sahli, B.; Eldali, A.; Aljuaid, M.; Al-Surimi, K. Person-centered care in a tertiary hospital through patients’ eyes: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 2021, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Chronic Disease. 2023. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/awarenessplateform/ChronicDisease/Pages/Diabetes.aspx (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Alkhateeb, M.; Althabaiti, K.; Ahmed, S.; Lövestad, S.; Khan, J. A systematic review of the determinants of job satisfaction in healthcare workers in health facilities in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Glob. Health Action 2025, 18, 2479910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.A.; Pavlova, M.; Alsubahi, N.; Ahmad, A.; Groot, W. Impact of the Cooperative Health Insurance System in Saudi Arabia on Universal Health Coverage—A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubahi, N.; Groot, W.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Pavlova, M. Patient-reported experience, patient-reported outcome and overall satisfaction with care: What matters most to people with diabetes? Prim. Care Diabetes 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engström, M.S.; Leksell, J.; Johansson, U.-B.; Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Borg, S.; Palaszewski, B.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S. A disease-specific questionnaire for measuring patient-reported outcomes and experiences in the Swedish National Diabetes Register: Development and evaluation of content validity, face validity, and test-retest reliability. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S.; Palaszewski, B.; Gerdtham, U.-G.; Fredrik, Ö.; Roos, P.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S. Patient-reported outcome measures and risk factors in a quality registry: A basis for more patient-centered diabetes care in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12223–12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, S.; Alarcón, O.; Coll, C.G.; Tropp, L.R.; García, H.A.V. The dual-focus approach to creating bilingual measures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1999, 30, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, S.; Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Palaszewski, B.; Engström, M.S.; Gerdtham, U.-G.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S. Patient-reported outcome and experience measures for diabetes: Development of scale models, differences between patient groups and relationships with cardiovascular and diabetes complication risk factors, in a combined registry and survey study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diabetes-Paho/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. 2023. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/diabetes (accessed on 23 September 2025).

| Variable | CR | Mean (SD) | AVE | Item | Mean (SD) | Factor Loadings * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREMs | 0.819 | 4.13 (1.28) | 0.357 | SD1 | 4.35 (0.97) | 0.490 |

| SD2 | 4.04 (1.2) | 0.608 | ||||

| SD3 | 3.53 (1.44) | 0.754 | ||||

| SD4 | 3.72 (1.37) | 0.782 | ||||

| SD5 | 3.47 (1.44) | 0.741 | ||||

| SD6 | 3.81 (1.28) | 0.756 | ||||

| SD7 | 4.00 (1.13) | 0.742 | ||||

| SD8 | 3.8 (1.32) | 0.688 | ||||

| SD9 | 4.21 (1.05) | 0.480 | ||||

| MD1 | 4.13 (1.28) | 0.172 | ||||

| MD2 | 3.28 (1.76) | 0.221 | ||||

| MD3 | 4.38 (1.01) | 0.195 | ||||

| PROMs feels | 0.663 | 3.52 (0.92) | 0.318 | F1 | 4.13 (0.84) | 0.555 |

| F2 | 3.92 (0.95) | 0.403 | ||||

| F3 | 2.72 (1.05) | 0.551 | ||||

| F4 | 2.59 (1.01) | 0.684 | ||||

| F5 | 4.24 (0.75) | 0.590 | ||||

| PROMs Worries | 0.786 | 2.28 (1.09) | 0.552 | W1 | 2.47 (1.1) | 0.714 |

| W2 | 2.24 (1.08) | 0.815 | ||||

| W3 | 2.13 (1.09) | 0.695 | ||||

| PROMs Capabilities | 0.758 | 4.25 (0.788) | 0.375 | C1 | 4.18 (0.83) | 0.772 |

| C2 | 4.37 (0.72) | 0.407 | ||||

| C3 | 4.2 (0.75) | 0.457 | ||||

| C4 | 4.31 (0.76) | 0.682 | ||||

| C5 | 4.19 (0.88) | 0.659 | ||||

| PROMs Barriers | 0.855 | 2.77 (0.992) | 0.602 | B1 | 2.57 (0.99) | 0.632 |

| B2 | 2.94 (1.04) | 0.657 | ||||

| B3 | 2.91 (0.97) | 0.816 | ||||

| B4 | 2.77 (0.97) | 0.862 | ||||

| B5 | 2.68 (0.99) | 0.878 | ||||

| PROMs Support | 0.853 | 4.33 (0.867) | 0.657 | SO1 | 4.38 (0.81) | 0.738 |

| SO2 | 4.28 (0.86) | 0.913 | ||||

| SO3 | 4.35 (0.84) | 0.769 |

| Patient-reported outcome measures PROMs | ||

| Variable | Number of items | Cronbach’s alpha |

| Feeling | 5 | 0.843 |

| Worrying | 3 | 0.785 |

| Capabilities | 5 | 0.758 |

| Barriers | 5 | 0.888 |

| Support from others | 3 | 0.845 |

| Total PROMs | 21 | 0.729 |

| Patient-reported experience measures PREMs | ||

| Variable | Number of items | Cronbach’s alpha |

| Support from the provider | 9 | 0.886 |

| Medical treatment | 3 | 0.398 |

| Total PREMs | 12 | 0.844 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-reported outcome variables | ||||||

| W | 1 | |||||

| B | 0.617 | 1 | ||||

| SO | 0.072 | 0.064 | 1 | |||

| C | 0.321 | 0.316 | 0.389 | 1 | ||

| F | 0.564 | 0.599 | 0.234 | 0.572 | 1 | |

| Patient-reported experience | 0.133 | 0.17 | 0.521 | 0.346 | 0.234 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alsubahi, N.; Alzahrani, A.; Alhazmi, F.; Alhaifani, R.; Alkhateeb, M. Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Swedish National Diabetes Registers Instrument for Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures. Healthcare 2026, 14, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010107

Alsubahi N, Alzahrani A, Alhazmi F, Alhaifani R, Alkhateeb M. Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Swedish National Diabetes Registers Instrument for Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsubahi, Nizar, Ahmed Alzahrani, Fahad Alhazmi, Roba Alhaifani, and Mohannad Alkhateeb. 2026. "Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Swedish National Diabetes Registers Instrument for Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010107

APA StyleAlsubahi, N., Alzahrani, A., Alhazmi, F., Alhaifani, R., & Alkhateeb, M. (2026). Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Swedish National Diabetes Registers Instrument for Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures. Healthcare, 14(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010107