Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer

Highlights

- Due to the long period between the first exposure and the first signs of lung cancer, occupational risk is under evaluated.

- Patients with occupational risk of lung cancers have longer time to diagnosis.

- Occupational hazards should be included in the risk assessment in order to reduce the time to diagnosis of patients with lung cancer.

- Follow-up of the workers exposed to lung carcinogens in their workplace could lead to an earlier detection of lung cancer.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Find out where to get professional help when you are ill?

- (b)

- Understand what your doctor says to you?

- (c)

- Use information the doctor gives you to make decisions about your illness?

- (d)

- Understand health warnings about behavior such as smoking, low physical activity and drinking too much?”

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Occupational Risk and the Total Diagnosis Interval Time

4.2. Smoking in the Context of Occupational Exposure and the Total Diagnosis Interval Time

4.3. Family History of Cancer in the Context of Occupational Exposure and the Total Diagnosis Interval Time

4.4. Pulmonary Diseases in the Context of Occupational Exposure and the Total Diagnosis Interval Time

4.5. Health Literacy in the Context of Occupational Exposure and the Total Diagnosis Interval Time

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Clinical Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TITD | Total Interval Time to Diagnosis |

| LC | Lung Cancer |

| LDCT | Low Dose Computed Tomography |

| USPSTF | U.S. Preventive Services Task Force |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| HLS-EU-Q16 | European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire, short version with 16 items |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- Cancer of the Lung and Bronchus—Cancer Stat Facts. SEER. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Lung Cancer Mortality Rate in Europe in 2022. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1418932/mortality-of-lung-cancer-in-europe/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 325, 962–970. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/33687470 (accessed on 6 December 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo, G.; Marangi, G.; Ballarin, M.N.; Bellini, E.; De Marzo, N.; Eder, M.; Finchi, A.; Gioffrè, F.; Marcolina, D.; Tessadri, G.; et al. Post-Occupational Health Surveillance of Asbestos Workers. Med. Lav. 2013, 104, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delva, F.; Margery, J.; Laurent, F.; Petitprez, K.; Pairon, J.-C.; RecoCancerProf Working Group. Medical Follow-up of Workers Exposed to Lung Carcinogens: French Evidence-Based and Pragmatic Recommendations. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, J.; Ge, T.; Jiang, M.; Jia, K.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; et al. Early Diagnosis of Lung Cancer: Which Is the Optimal Choice? Aging 2021, 13, 6214–6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malalasekera, A.; Nahm, S.; Blinman, P.L.; Kao, S.C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Vardy, J.L. How Long Is Too Long? A Scoping Review of Health System Delays in Lung Cancer. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The NHS Cancer Plan. Available online: https://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Society/documents/2003/08/26/cancerplan.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Obayashi, K.; Shimizu, K.; Nakazawa, S.; Nagashima, T.; Yajima, T.; Kosaka, T.; Atsumi, J.; Kawatani, N.; Yazawa, T.; Kaira, K.; et al. The Impact of Histology and Ground-Glass Opacity Component on Volume Doubling Time in Primary Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 5428–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; IJzerman, M.J.; Oberoi, J.; Karnchanachari, N.; Bergin, R.J.; Franchini, F.; Druce, P.; Wang, X.; Emery, J.D. Time to Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer: A Systematic Overview of Risk Factors, Interventions and Impact on Patient Outcomes. Lung Cancer 2022, 166, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucă, A.; Băban, A. Psychological Factors and Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer Related Pain. Rom. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 55, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantonio, R.; Cofini, V.; Tobia, L.; Mastrangeli, G.; Guerriero, P.; Cipollone, C.; Fabiani, L. Assessing Occupational Chemical Risk Perception in Construction Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barattucci, M.; Ramaci, T.; Matera, S.; Vella, F.; Gallina, V.; Vitale, E. Differences in Risk Perception Between the Construction and Agriculture Sectors: An Exploratory Study with a Focus on Carcinogenic Risk. Med. Lav. 2025, 116, 16796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, B.; Olsson, A.; Bouaoun, L.; Hall, A.; Hadji, M.; Rashidian, H.; Naghibzadeh-Tahami, A.; Marzban, M.; Najafi, F.; Haghdoost, A.A.; et al. Lung Cancer Risk in Relation to Jobs Held in a Nationwide Case–Control Study in Iran. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 79, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, T.C.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Candal-Pedreira, C.; López-López, R.; Torres-Durán, M.; Enjo-Barreiro, J.R.; Provencio, M.; Parente-Lamelas, I.; Vidal-García, I.; Martínez, C.; et al. Occupation as a Risk Factor of Small Cell Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, S.B.; Dickens, B. Screening for Occupational Lung Cancer: An Unprecedented Opportunity. Clin. Chest Med. 2020, 41, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.L.; Xu, N.N.; Senthil, P.; Srinivasan, D.; Lee, H.; Gazelle, G.S.; Chelala, L.; Zheng, W.; Fintelmann, F.J.; Sequist, L.V.; et al. Pack-Year Smoking History: An Inadequate and Biased Measure to Determine Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2026–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, M.A.; Forray, A.I.; Van den Broucke, S.; Chereches, R.M. Measuring Health Literacy in Romania: Validation of the HLS-EU-Q16 Survey Questionnaire. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C.; Lastrucci, V.; Mantwill, S.; Vettori, V.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Florence Health Literacy Research Group. Measuring Health Literacy in Italy: A Validation Study of the HLS-EU-Q16 and of the HLS-EU-Q6 in Italian Language, Conducted in Florence and Its Surroundings. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Sanita 2019, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonjans, F. Inter-Rater Agreement (Kappa)—Free MedCalc Online Statistical Calculator. MedCalc. Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/en/calc/kappa.php (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Peters, C.E.; Ge, C.B.; Hall, A.L.; Davies, H.W.; Demers, P.A. CAREX Canada: An Enhanced Model for Assessing Occupational Carcinogen Exposure. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 72, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddone, E.; D’Amato, L.; Pernetti, R.; Madeo, D.; Toschi, L.; Farinatti, S.; Riva, G.; Spina, L.; Ferrante, L.; Conde, C.; et al. Exposure to Occupational Carcinogens and Non-Oncogene Addicted Phenotype in Lung Cancer: Results from a Real-Life Observational Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pélissier, C.; Dutertre, V.; Fournel, P.; Gendre, I.; Michel Vergnon, J.; Kalecinski, J.; Tinquaut, F.; Fontana, L.; Chauvin, F. Design and Validation of a Self-Administered Questionnaire as an Aid to Detection of Occupational Exposure to Lung Carcinogens. Public Health 2017, 143, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidrich, J.; Centmayer, A.; Wolff, C.; Wiethege, T.; Taeger, D.; Duell, M.; Harth, V. A Nationwide Program for Lung Cancer Screening by Low-Dose CT among Formerly Asbestos-Exposed Workers in Germany: Concept and Participation. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, S130–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, S.; Ringen, K.; Dement, J.M.; Straif, K.; Christine Oliver, L.; Algranti, E.; Nowak, D.; Ehrlich, R.; McDiarmid, M.A.; Miller, A.; et al. Occupational Lung Cancer Screening: A Collegium Ramazzini Statement. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2024, 67, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, S.B.; Manowitz, A.; Miller, J.A.; Frederick, J.S.; Onyekelu-Eze, A.C.; Widman, S.A.; Pepper, L.D.; Miller, A. Yield of Low-Dose Computerized Tomography Screening for Lung Cancer in High-Risk Workers: The Case of 7189 US Nuclear Weapons Workers. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tossavainen, A. Asbestos, Asbestosis, and Cancer: The Helsinki Criteria for Diagnosis and Attribution. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1997, 23, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Koh, D.-H.; Park, C.-Y. Decision Tree of Occupational Lung Cancer Using Classification and Regression Analysis. Saf. Health Work 2010, 1, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottai, M.; Selander, J.; Pershagen, G.; Gustavsson, P. Age at Occupational Exposure to Combustion Products and Lung Cancer Risk among Men in Stockholm, Sweden. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, N.N.D.; Khatkar, M. Sample Size Calculator for Estimating a Proportion. Available online: https://statulator.com/SampleSize/ss1P.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Huh, D.-A.; Chae, W.-R.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Moon, K.-W. Disease Latency According to Asbestos Exposure Characteristics among Malignant Mesothelioma and Asbestos-Related Lung Cancer Cases in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, L.; Pentimone, F.; Cavone, D.; Caputi, A.; Sponselli, S.; Fragassi, F.; Dicataldo, F.; Luisi, V.; Delvecchio, G.; Giannelli, G.; et al. Clinical Investigation of Former Workers Exposed to Asbestos: The Health Surveillance Experience of an Italian University Hospital. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1411910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, B.W.A.; Bovio, N.; Arveux, P.; Bergeron, Y.; Bulliard, J.-L.; Fournier, E.; Germann, S.; Konzelmann, I.; Maspoli, M.; Rapiti, E.; et al. Estimating 10-Year Risk of Lung and Breast Cancer by Occupation in Switzerland. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1137820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandanach, C.; Mateș, D.; Jinga, V.; Otelea, M. Occupational Domains and Age at Onset of Lung Cancer Diagnosis. Romanian J. Occup. Med. 2024, 75, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Pond, G.R.; Tremblay, A.; Johnston, M.; Goss, G.; Nicholas, G.; Martel, S.; Bhatia, R.; Liu, G.; Schmidt, H.; et al. Risk Perception Among a Lung Cancer Screening Population. Chest 2021, 160, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoPiccolo, J.; Gusev, A.; Christiani, D.C.; Jänne, P.A. Lung Cancer in Patients Who Have Never Smoked—An Emerging Disease. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.S.; Bælum, J.; Rasmussen, J.; Dahl, S.; Olsen, K.E.; Albin, M.; Hansen, N.C.; Sherson, D. Occupational Asbestos Exposure and Lung Cancer—A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2014, 69, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintos, J.; Parent, M.-E.; Richardson, L.; Siemiatycki, J. Occupational Exposure to Diesel Engine Emissions and Risk of Lung Cancer: Evidence from Two Case-Control Studies in Montreal, Canada. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.R.; Hung, R.J.; Tsao, M.-S.; Shepherd, F.A.; Johnston, M.R.; Narod, S.; Rubenstein, W.; McLaughlin, J.R. Lung Cancer Risk in Never-Smokers: A Population-Based Case-Control Study of Epidemiologic Risk Factors. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, A.; Guha, N.; Bouaoun, L.; Kromhout, H.; Peters, S.; Siemiatycki, J.; Ho, V.; Gustavsson, P.; Boffetta, P.; Vermeulen, R.; et al. Occupational Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Lung Cancer Risk: Results from a Pooled Analysis of Case-Control Studies (SYNERGY). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronk, A.; Coble, J.; Ji, B.-T.; Shu, X.-O.; Rothman, N.; Yang, G.; Gao, Y.-T.; Zheng, W.; Chow, W.-H. Occupational Risk of Lung Cancer among Lifetime Non-Smoking Women in Shanghai, China. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 66, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, A.; Bouaoun, L.; Schüz, J.; Vermeulen, R.; Behrens, T.; Ge, C.; Kromhout, H.; Siemiatycki, J.; Gustavsson, P.; Boffetta, P.; et al. Lung Cancer Risks Associated with Occupational Exposure to Pairs of Five Lung Carcinogens: Results from a Pooled Analysis of Case-Control Studies (SYNERGY). Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Goodley, P.; Alcala, K.; Guida, F.; Kaaks, R.; Vermeulen, R.; Downward, G.S.; Bonet, C.; Colorado-Yohar, S.M.; Albanes, D.; et al. Evaluation of Risk Prediction Models to Select Lung Cancer Screening Participants in Europe: A Prospective Cohort Consortium Analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e614–e624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Mucci, L.; Albanes, D.; Landi, M.T.; Caporaso, N.E.; Lam, S.; Tardon, A.; et al. Impact of Individual Level Uncertainty of Lung Cancer Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) on Risk Stratification. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, A.L.; Adcock, I.M. The Relationship between COPD and Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2015, 90, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Kang, D.; Shin, S.H.; Yoo, K.-H.; Rhee, C.K.; Suh, G.Y.; Kim, H.; Shim, Y.M.; Guallar, E.; Cho, J.; et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Lung Cancer Incidence in Never Smokers: A Cohort Study. Thorax 2020, 75, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioboata, R.; Balteanu, M.A.; Mitroi, D.M.; Vrabie, S.C.; Vlasceanu, S.G.; Andrei, G.M.; Riza, A.L.; Streata, I.; Zlatian, O.M.; Olteanu, M. Beyond Smoking: Emerging Drivers of COPD and Their Clinical Implications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.-X.; Liao, H.-J.; Hu, J.-J.; Xiong, H.; Cai, X.-Y.; Ye, D.-W. Global Burden of Lung Cancer Attributable to Household Fine Particulate Matter Pollution in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990 to 2019. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Dai, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, R.; He, D.; He, J.; Liang, H. Global Lung Cancer Burden Attributable to Air Fine Particulate Matter and Tobacco Smoke Exposure: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Transnational Inequalities from 1990 to 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criner, G.J.; Agusti, A.; Borghaei, H.; Friedberg, J.; Martinez, F.J.; Miyamoto, C.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Celli, B.R. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Lung Cancer: A Review for Clinicians. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. J. COPD Found. 2022, 9, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, N.; Park, C.-M.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, S.-M.; Yim, J.-J.; Yoo, C.-G.; Kim, Y.W.; Han, S.K.; Lee, C.-H. Lung Cancer Risk among Patients with Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema. Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, G.M.; D’Agnano, V.; Piloni, D.; Saracino, L.; Lettieri, S.; Mariani, F.; Lancia, A.; Bortolotto, C.; Rinaldi, P.; Falanga, F.; et al. The Oncogenic Landscape of the Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Narrative Review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 472–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.-A.W.; Dobelle, M.; Padilla, M.; Agovino, M.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Hashim, D.; Boffetta, P. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrys, E.; Burt, J.; Rubin, G.; Emery, J.D.; Walter, F.M. The Influence of Health Literacy on the Timely Diagnosis of Symptomatic Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venchiarutti, R.L.; Clark AM, J.R.; Palme, C.E.; Dwyer, P.; Tahir, A.R.M.; Hill, J.; Ch’ng, S.; Elliott, M.S.; Young, J.M. Associations between Patient-Level Health Literacy and Diagnostic Time Intervals for Head and Neck Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Head. Neck 2024, 46, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cîmpeanu, O.; Liliac, I.M.; Pirici, D.-N.; Olteanu, M.; Streba, C.-T. Analysis of Imaging, Pathology and Demographic Data of Lung Cancer Patients Diagnosed in a Tertiary Medical Center in the South-West Region of Romania. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2025, 51, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, B.; Diaconu, C.C.; Cucu, A.; Bogdan, M.A.; Toma, C.L. The Trend of Epidemiological Data in Patients with Lung Cancer Addressed to a Romanian Tertiary Pneumology Service. Arch. Balk. Med. Union. 2019, 54, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancusa, V.M.; Trusculescu, A.A.; Constantinescu, A.; Burducescu, A.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Manolescu, D.L.; Traila, D.; Wellmann, N.; Oancea, C.I. Temporal Trends and Patient Stratification in Lung Cancer: A Comprehensive Clustering Analysis from Timis County, Romania. Cancers 2025, 17, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menvielle, G.; Boshuizen, H.; Kunst, A.E.; Vineis, P.; Dalton, S.O.; Bergmann, M.M.; Hermann, S.; Veglia, F.; Ferrari, P.; Overvad, K.; et al. Occupational Exposures Contribute to Educational Inequalities in Lung Cancer Incidence among Men: Evidence from the EPIC Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Fafin-Lefevre, M.; Morello, R.; Boullard, L.; Clin, B. Compensation for Patients with Work-Related Lung Cancers: Value of Specialised Occupational Disease Consultations to Reduce Under-Recognition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Cases | Controls | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at dg (mean ± SD) | 63.35 ± 10.22 | 63.63 ± 8.81 | 63.19 ± 10.96 | 0.71 |

| Gender (no of Women, %) | 44 (40%) | 12 (31.57%) | 32 (44.44%) | 0.19 |

| Level of education (no. of undergraduate, %) | 81 (73.64%) | 32 (84.21%) | 49 (68.05%) | 0.07 |

| Smokers (no, %) | 85 (77.27%) | 30 (78.94%) | 55 (76.39%) | 0.76 |

| Heavy smokers (no, %) | 77 (70%) | 29 (73.31%) | 48 (66.67%) | 0.29 |

| No. of years of smoking | 31.8 ± 20.22 | 33.24 ± 20.75 | 31.36 ± 19.95 | 0.31 |

| No. of packs-years (mean ± SD) | 38.05 ± 30.28 | 39.24 ± 29.07 | 37.42 ± 31.09 | 0.77 |

| TIITD (months, mean ± SD) | 3.41 ± 5.12 | 4.60 ± 5.88 | 2.77 ± 4.58 | 0.03 |

| No. of patients diagnosed > 3.5 months (no, %) | 29 (26.36%) | 16 (55.17%) | 13 (44.83%) | 0.006 |

| Family history of pulmonary cancer (no, %) | 11 (32.50%) | 4 (10.52%) | 7 (9.72%) | 0.89 |

| Pulmonary diseases associated with high risk of LC (no, %) | 36 (32.72%) | 18 (47.37%) | 18 (25%) | 0.02 |

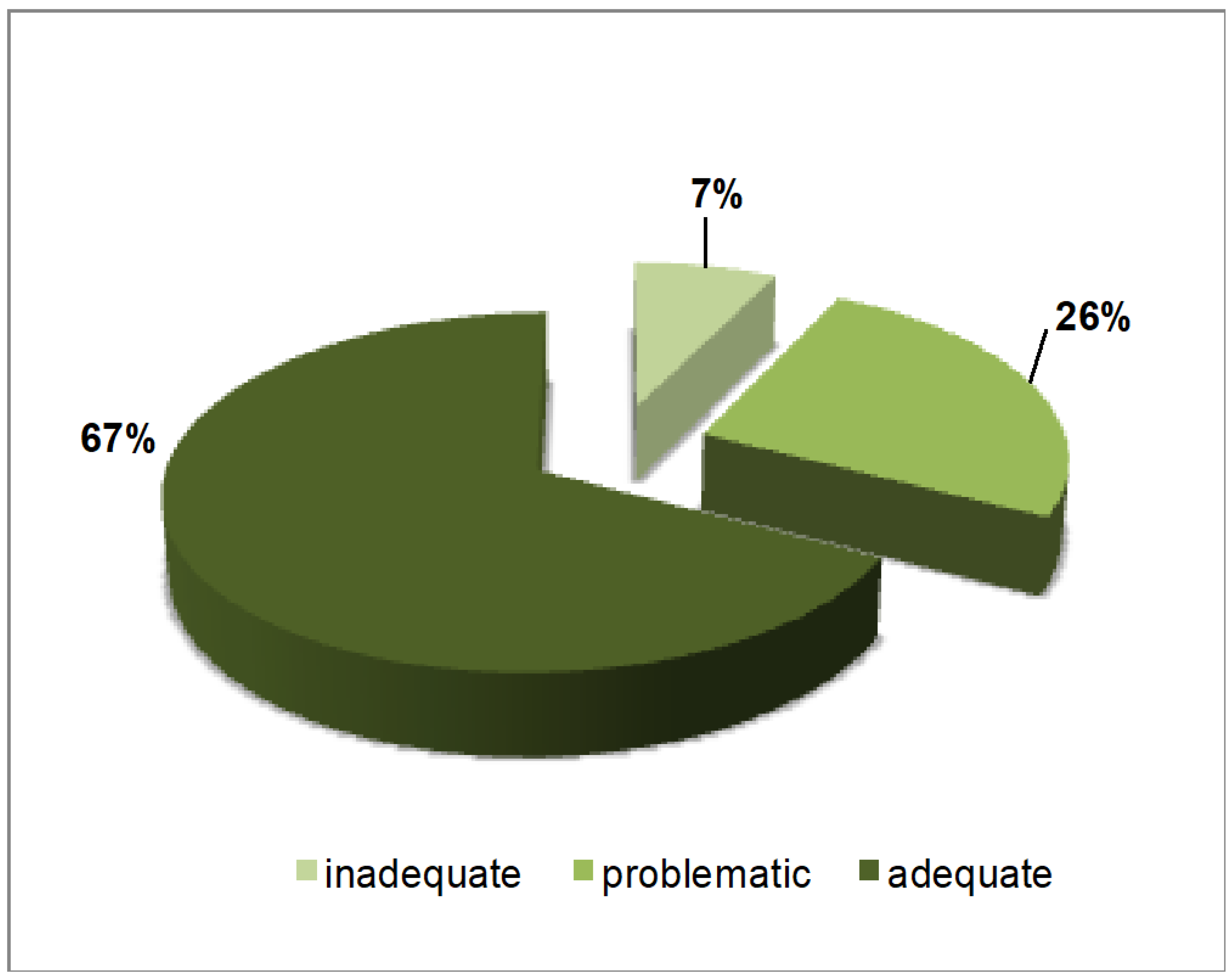

| HLS-EU-Q16 total score (mean, SD) | 13.25 ± 2.97 | 12.97 ± 2.71 | 13.40 ± 3.10 | 0.24 |

| Q related to the easiness to find out where to obtain healthcare help | 3.32 ± 0.59 | 3.26 ± 0.60 | 3.43 ± 0.57 | 0.14 |

| Q related to the understanding of health warnings about smoking | 3.2 ± 0.76 | 3.21 ± 0.66 | 3.19 ± 0.81 | 0.82 |

| Q related to understanding doctors’ messages | 3.2 ± 0.78 | 3.15 ± 0.71 | 3.22 ± 0.81 | 0.50 |

| Q related to usage of the information the doctor gives in making decisions | 3.26 ± 0.64 | 3.16 ± 0.68 | 3.32 ± 0.62 | 0.22 |

| VAR | Odds Ratio | LCL | UCL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TITD cases/controls (controls as reference) | 3.14 | 1.22 | 8.08 | 0.02 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 0.13 |

| Sex (women as reference) | 1.33 | 0.45 | 3.96 | 0.61 |

| Level of education | 0.90 | 0.64 | 1.27 | 0.56 |

| No of packs-years | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.81 |

| Family history of cancer | 0.25 | 0.03 | 2.17 | 0.21 |

| HLS-EU-Q16 score | 1.02 | 0.84 | 1.24 | 0.84 |

| Pulmonary diseases associated with high risk of LC | 1.02 | 0.38 | 2.71 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mandanach, C.; Maftei, A.; Țocan, O.M.; Toma, C.L.; Oțelea, M.R. Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer. Healthcare 2026, 14, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010106

Mandanach C, Maftei A, Țocan OM, Toma CL, Oțelea MR. Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandanach, Cristina, Andreea Maftei, Ocxana Maria Țocan, Claudia Lucia Toma, and Marina Ruxandra Oțelea. 2026. "Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010106

APA StyleMandanach, C., Maftei, A., Țocan, O. M., Toma, C. L., & Oțelea, M. R. (2026). Neglected Occupational Risk Factors—A Contributor to Diagnostic Delays in Lung Cancer. Healthcare, 14(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010106

_Rachiotis.png)