A Psychometric Evaluation of the Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS) in Turkish Older Adults with Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Language and Content Validity

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Data Collection Form

2.4.1. Diabetes Identification Form

2.4.2. Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyse the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics among older adults with diabetes. Additionally, mean and standard deviation (SD) values were calculated for the total scale and its subdimensions to summarize the overall scoring patterns.

- Language Validity: The scale underwent translation and back-translation procedures, followed by expert feedback from 10 specialists. The agreement among experts was evaluated using Kendall’s W test. A pre-test of the scale was conducted with participants.

- Content Validity: To assess content validity, Lawshe’s technique was employed, and both the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI) were calculated based on expert evaluations.

- Sample Adequacy: The adequacy of the sample for factor analysis was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test.

- Data Suitability for Factor Analysis: The appropriateness of the data for factor analysis was evaluated using Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Inter-item correlations were reviewed, and no barriers against factor analysis were identified.

- Construct Validity: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Conducted to explore the factor structure of the scale. For the validity analysis, the dataset was divided into two subsets: the first subset was used for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), while the second subset was utilized for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). As part of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Principal Component Analysis was used for factor extraction, and Varimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization was applied as the rotation method.

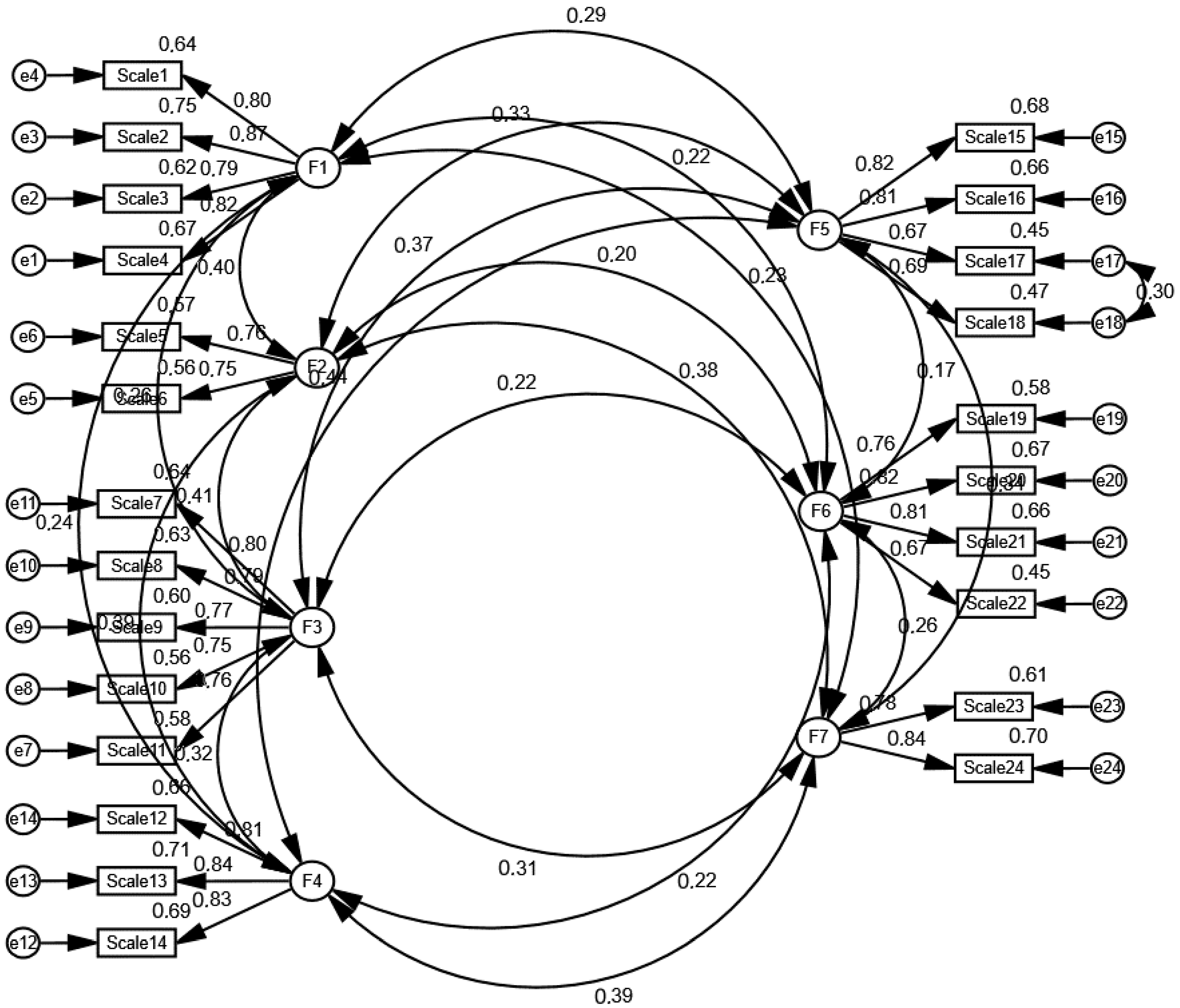

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the model fit indices.

- Test–Retest Reliability: The scale was re-administered to the first 200 participants after four weeks, and test–retest correlations were calculated.

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Language Validity and Content Validity

3.3. Construct Validity

3.4. Internal Consistency Analysis

4. Discussion

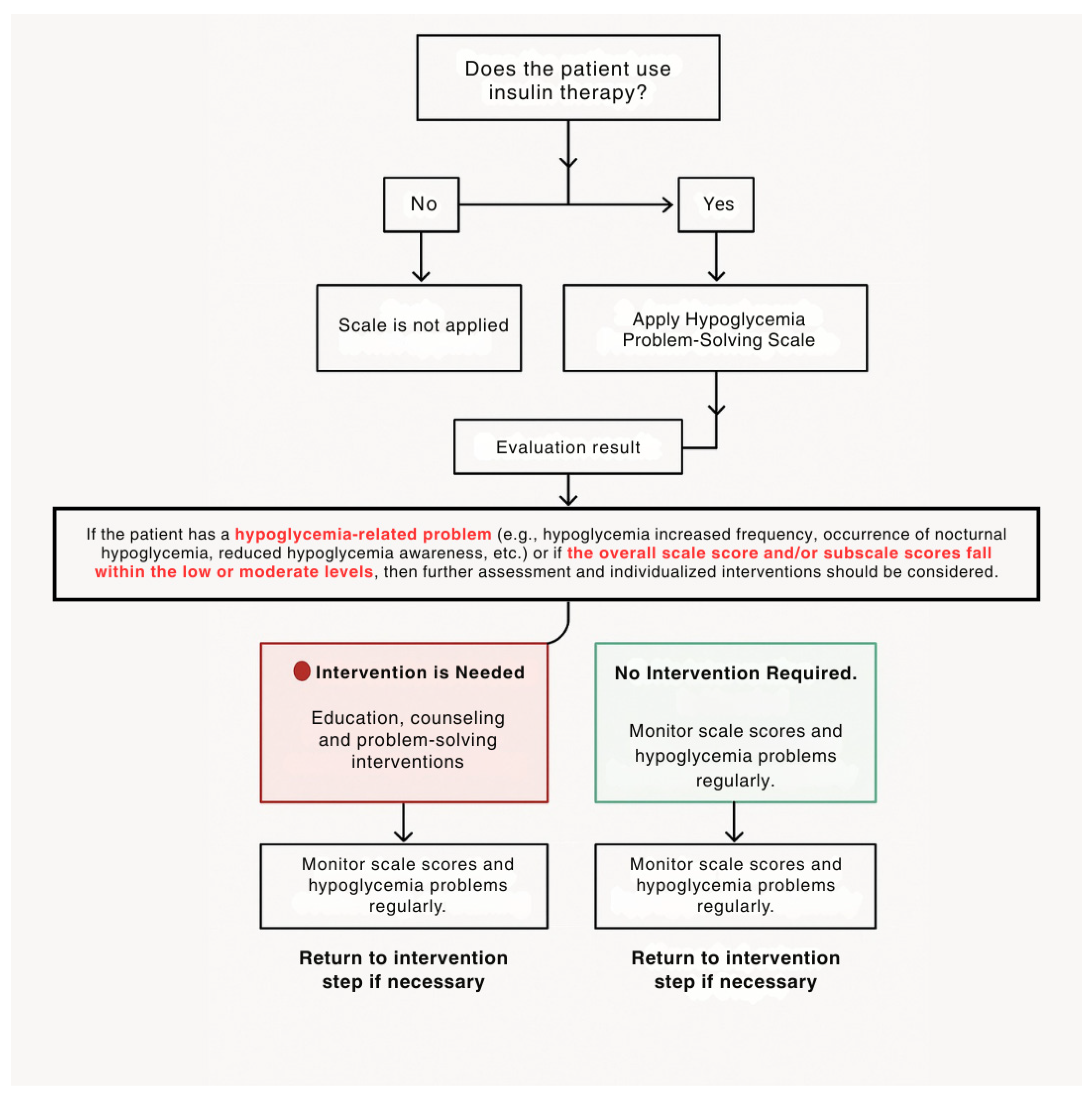

- Selection of the Expert Panel: Experts were selected based on their clinical experience (≥5 years) and their involvement in patient follow-up or research related to hypoglycemia.

- Evaluation of Scale Score Ranges: Open-ended questions were presented to the experts regarding which score ranges for the total score (0–96) and seven subscales of the HPSS would represent low, moderate, and high levels.

- Collection of Opinions and Consensus Building: The number of experts who agreed on each proposed range was counted. Score ranges for which at least 85% of the experts (e.g., 6 out of 7) reached agreement were defined as “accepted levels”.

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossain, M.J.; Al-Mamun, M.; Islam, M.R. Diabetes mellitus, the fastest growing global public health concern: Early detection should be focused. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 204, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 6. Glycemic Goals and Hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S128–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellary, S.; Kyrou, I.; Brown, J.E.; Bailey, C.J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: Clinical considerations and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlaut, R.R.; Dogbey, G.Y.; Schwartz, F.L.; Marling, C.R.; Shubrook, J.H. Hypoglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes—More Common Than You Think: A Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J. Management of hypoglycemia in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 131, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunti, K.; Alsifri, S.; Aronson, R.; Cigrovski Berković, M.; Enters-Weijnen, C.; Forsén, T.; Galstyan, G.; Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, P.; Goldfracht, M.; Gydesen, H. Rates and predictors of hypoglycaemia in 27,585 people from 24 countries with insulin-treated type 1 and type 2 diabetes: The global HAT study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, M.; Bhatia, A.; Munshi, M. Review of Hypoglycemia in the Older Adult: Clinical Implications and Management. Can. J. Diabetes 2016, 40, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzen, L.; Schultes, B.; Meyhöfer, S.M.; Meyhöfer, S. Hypoglycemia Unawareness—A Review on Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.L.; Kanapka, L.G.; Miller, K.M.; Ahmann, A.J.; Chaytor, N.S.; Fox, S.; Kiblinger, L.; Kruger, D.; Levy, C.J.; Peters, A.L.; et al. Hypoglycemia and Glycemic Control in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Baseline Results from the WISDM Study. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 15, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Y.; Wong, I.C.; Whittlesea, C.; Alwafi, H.; Abuirmeileh, A.; Alsairafi, Z.K.; Turkistani, F.M.; Bokhari, N.S.; Beykloo, M.Y.; Al-Taweel, D.; et al. Attitudes and perceptions towards hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, S.; Kato, K.; Hata, S.; Nishimura, E.; Araki, R.; Kouyama, K.; Hatao, M.; Matoba, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Domichi, M.; et al. Association of hypoglycemia problem-solving abilities with severe hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes: A Poisson regression analysis. Diabetol. Int. 2024, 15, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, K.P.; Sutherland, J.A.; Majid, H.M.; Hill-Briggs, F. Evidence-based behavioral treatments for diabetes: Problem-solving therapy. Diabetes Spectrum 2011, 24, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, F.L.; Juang, J.H.; Lin, C.H. Development and validation of the hypoglycaemia problem-solving scale for people with diabetes mellitus. J. Int. Med. Res. 2016, 44, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Lin, C.H.; Lin, C.L.; Juang, J.H. Effectiveness of a Problem-Solving Program in Improving Problem-Solving Ability and Glycemic Control for Diabetics with Hypoglycemia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Zurilla, T.J.; Goldfried, M.R. Problem solving and behavior modification. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1971, 78, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günbaş, M.; Büyükkaya Besen, D.; Dervişoğlu, M. Assessing psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Diabetes Caregiver Activity and Support Scale (D-CASS). Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şencan, H. Reliability and Validity in Social and Behavioral Measurements, 1st ed.; Seçkin Publishing: Ankara, Türkiye, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kartal, M.; Bardakçı, S. SPSS and AMOS Reliability and Validity Analyses with Practical Examples, 1st ed.; Akademisyen Publishing: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio: Revisiting the Original Methods of Calculation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: A guide for researchers. Commun. Methods Meas. 2018, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emral, R.; Tetiker, T.; Sahin, I.; Sari, R.; Kaya, A.; Yetkin, İ.; IO HAT investigator group. An international survey on hypoglycemia among insulin-treated type I and type II diabetes patients: Turkey cohort of the non-interventional IO HAT study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.T.; Armenakis, A.A.; Feild, H.S.; Harris, S.G. Readiness for Organizational Change: The Systematic Development of a Scale. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2007, 43, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbo, B.D. Standard-Setting Methodology: Establishing Performance Standards and Setting Cut-Scores to Assist Score İnterpretation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± Std.) | 72 ± 5.5 |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Female | 323 (51.8%) |

| Male | 300 (48.2%) |

| Education n (%) | |

| Illiterate | 42 (6.7%) |

| Elementary School | 302 (48.5%) |

| High School | 157 (25.2%) |

| University | 122 (19.6%) |

| Time of Diagnosis Min–Max (Mean ± Std.) | 1–39 (13.31 ± 7.97) |

| Treatment n (%) | |

| Insulin | 269 (43.2%) |

| Insulin + OAD | 354 (56.8%) |

| Hypoglycemia Frequency in the Last 6 Months n (%) | |

| 1–5 times | 300 (48.2%) |

| 6–10 times | 116 (18.6%) |

| 11–15 times | 99 (15.9%) |

| ≥16 times | 108 (17.3%) |

| Factors | Item Number/Item Content | Factor Loading | Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem-solving perception | 1R. When my attempt to prevent hypoglycaemia fails, I become discouraged and cannot think clearly. | 0.83 | 0.47 |

| 2R. The difficulty I encounter in preventing hypoglycaemia makes me feel depressed or angry. | 0.87 | 0.45 | |

| 3R. I often worry about how to prevent hypoglycaemia but have not taken any action to address it. | 0.83 | 0.45 | |

| 4R. When I cannot prevent hypoglycaemia I feel stupid. | 0.83 | 0.47 | |

| Detection control | 5. I know how to handle hypoglycaemia. | 0.83 | 0.44 |

| 6. I do not give up when my initial attempt to effectively prevent hypoglycaemia fails, and I believe that I will ultimately find the best approach to solve it. | 0.81 | 0.42 | |

| Identifying problem attributes | 7. When hypoglycaemia occurs, I examine for any event that may contribute to the occurrence of hypoglycaemia. | 0.81 | 0.52 |

| 8. When my efforts to prevent hypoglycaemia are ineffective, I return to where I made the mistakes and attempt other methods. | 0.81 | 0.51 | |

| 9. When I am not satisfied with the results of preventing hypoglycaemia, I will find a better method and attempt it again. | 0.79 | 0.50 | |

| 10. When my attempt to prevent hypoglycaemia fails, I will analyse and identify my mistake. | 0.81 | 0.43 | |

| 11. To prevent hypoglycaemia, I attempt to learn as much information on the occurrence of hypoglycaemia as possible. | 0.76 | 0.53 | |

| Setting problem-solving goals | 12. When I attempt to manage hypoglycaemia, I remember all the goals that I have set. | 0.83 | 0.48 |

| 13. When attempting to prevent hypoglycaemia, I set a goal so that I know what I need to achieve. | 0.85 | 0.46 | |

| 14. I will attempt to prevent hypoglycaemia and achieve all the goals I have set. | 0.85 | 0.48 | |

| Seeking preventive strategies | 15. I usually speak with my family when I am attempting to prevent hypoglycaemia. | 0.78 | 0.50 |

| 16. I speak with health professionals when hypoglycaemia prevention becomes complex and difficult. | 0.79 | 0.48 | |

| 17. When hypoglycaemia prevention becomes complex and difficult, I seek help from friends or pay close attention to my physical changes. | 0.79 | 0.47 | |

| 18. When hypoglycaemia prevention becomes complex and difficult, I learn how to prevent hypoglycaemia from people who have the same problem as mine. | 0.82 | 0.46 | |

| Evaluating strategies | 19. After implementing the method for hypoglycaemia prevention, I evaluate the effectiveness of this method in preventing hypoglycaemia. | 0.82 | 0.37 |

| 20. When preventing hypoglycaemia, I attempt my own method to increase the chance of success. | 0.86 | 0.34 | |

| 21. When determining the best hypoglycaemia prevention method, I attempt to predict the possible outcome. | 0.85 | 0.35 | |

| 22. I understand hypoglycaemia prevention is one of the problems that must be resolved in diabetic care. | 0.70 | 0.45 | |

| Immediate management | 23R. When I experience hypoglycaemia, I usually snack, stop all activity, or stop insulin injections, and do not think about prevention. | 0.86 | 0.41 |

| 24R. To me, hypoglycaemia is an easily manageable problem and does not need to be a concern. | 0.86 | 0.42 | |

| Total variance: 74.22% | |||

| Items | Groups | n | Mean | Standard Deviation | 5% Confidence Interval Lower–Upper | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.20 | 0.82 | [−0.91–0.60] | −9.67 | 303.96 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.95 | 0.59 | |||||

| Item 2 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.22 | 0.82 | [−0.95–0.64] | −9.94 | 318.05 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 2.02 | 0.64 | |||||

| Item 3 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.22 | 0.82 | [−0.81–0.52] | −8.92 | 285.14 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.89 | 0.52 | |||||

| Item 4 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.24 | 0.85 | [−0.87–0.56] | −9.05 | 295.37 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.96 | 0.57 | |||||

| Item 5 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.33 | 0.8 | [−0.67–0.37] | −6.83 | 303.24 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.85 | 0.57 | |||||

| Item 6 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.30 | 0.76 | [−0.67–0.37] | −7.02 | 320.09 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.82 | 0.6 | |||||

| Item 7 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.13 | 0.67 | [−0.95–0.69] | −12.4 | 318.19 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.95 | 0.53 | |||||

| Item 8 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.15 | 0.67 | [−1.02–0.76] | −13.76 | 313.06 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 2.04 | 0.5 | |||||

| Item 9 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.19 | 0.7 | [−0.95–0.68] | −12.17 | 312.38 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 2.01 | 0.52 | |||||

| Item 10 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.26 | 0.66 | [−0.83–0.56] | −10.36 | 327.11 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.96 | 0.56 | |||||

| Item 11 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.16 | 0.71 | [−0.95–0.68] | −11.82 | 317.25 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.98 | 0.55 | |||||

| Item 12 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.28 | 0.8 | [−0.84–0.54] | −9.11 | 307.45 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.98 | 0.58 | |||||

| Item 13 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.23 | 0.8 | [−0.84–0.53] | −8.9 | 314.05 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.92 | 0.61 | |||||

| Item 14 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.20 | 0.76 | [−0.87–0.58] | −9.98 | 309.52 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.93 | 0.56 | |||||

| Item 15 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.11 | 0.75 | [−0.98–0.69] | −11.03 | 328.26 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.95 | 0.64 | |||||

| Item 16 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.13 | 0.67 | [−0.95–0.68] | −11.94 | 330.62 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.95 | 0.59 | |||||

| Item 17 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.21 | 0.74 | [−0.90–0.61] | −10.29 | 325.23 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.97 | 0.61 | |||||

| Item 18 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.19 | 0.76 | [−0.93–0.63] | −10.12 | 328.67 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.98 | 0.55 | |||||

| Item 19 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.32 | 0.73 | [−0.71–0.43] | −7.93 | 319.41 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.89 | 0.58 | |||||

| Item 20 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.37 | 0.8 | [−0.80–0.49] | −8.39 | 310.48 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 2.02 | 0.61 | |||||

| Item 21 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.34 | 0.8 | [−0.75–0.44] | −7.57 | 319.752 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.94 | 0.63 | |||||

| Item 22 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.21 | 0.69 | [−0.90–0.63] | −11.06 | 326.525 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.98 | 0.58 | |||||

| Item 23 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.31 | 0.83 | [−0.80–0.48] | −7.9 | 315.922 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.95 | 0.64 | |||||

| Item 24 | Lower Group | 169 | 1.27 | 0.79 | [−0.78–0.49] | −8.53 | 303.8 | <0.001 |

| Upper Group | 169 | 1.91 | 0.56 |

| Item—Total Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Scale Mean If Item Deleted | Scale Variance If Item Deleted | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

| Item 1 | 37.87 | 68.91 | 0.87 |

| Item 2 | 37.83 | 69.01 | 0.87 |

| Item 3 | 37.85 | 69.35 | 0.87 |

| Item 4 | 37.83 | 69.08 | 0.87 |

| Item 5 | 37.83 | 69.65 | 0.87 |

| Item 6 | 37.85 | 70.02 | 0.87 |

| Item 7 | 37.89 | 69.00 | 0.87 |

| Item 8 | 37.85 | 68.98 | 0.87 |

| Item 9 | 37.82 | 69.12 | 0.87 |

| Item 10 | 37.83 | 70.08 | 0.87 |

| Item 11 | 37.83 | 68.69 | 0.87 |

| Item 12 | 37.82 | 68.97 | 0.87 |

| Item 13 | 37.82 | 69.13 | 0.87 |

| Item 14 | 37.83 | 69.11 | 0.87 |

| Item 15 | 37.87 | 68.72 | 0.87 |

| Item 16 | 37.85 | 69.25 | 0.87 |

| Item 17 | 37.83 | 69.07 | 0.87 |

| Item 18 | 37.83 | 69.07 | 0.87 |

| Item 19 | 37.82 | 70.49 | 0.87 |

| Item 20 | 37.78 | 70.51 | 0.88 |

| Item 21 | 37.80 | 70.59 | 0.88 |

| Item 22 | 37.84 | 69.83 | 0.87 |

| Item 23 | 37.78 | 69.61 | 0.87 |

| Item 24 | 37.84 | 69.76 | 0.87 |

| Total Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.88 | |||

| HPSS | Low Level | Moderate Level | High Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPSS Total | ≤49 | 50–79 | 80–96 |

| HPSS Subscales | |||

| Problem-Solving Perception | 0–5 | 6–11 | 12–16 |

| Detection Control | 0–3 | 4–6 | 7–8 |

| Identifying Problem Attributes | 0–7 | 8–14 | 15–20 |

| Setting Problem-Solving Goals | 0–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 |

| Seeking Preventive Strategies | 0–5 | 6–11 | 12–16 |

| Evaluating Strategies | 0–5 | 6–11 | 12–16 |

| Immediate Management | 0–3 | 4–6 | 7–8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dervişoğlu, M.; Büyükkaya Besen, D.; Günbaş, M.; Ertaş, M.; Emekdaş, B. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS) in Turkish Older Adults with Diabetes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13090997

Dervişoğlu M, Büyükkaya Besen D, Günbaş M, Ertaş M, Emekdaş B. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS) in Turkish Older Adults with Diabetes. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):997. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13090997

Chicago/Turabian StyleDervişoğlu, Merve, Dilek Büyükkaya Besen, Merve Günbaş, Mehtap Ertaş, and Barış Emekdaş. 2025. "A Psychometric Evaluation of the Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS) in Turkish Older Adults with Diabetes" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13090997

APA StyleDervişoğlu, M., Büyükkaya Besen, D., Günbaş, M., Ertaş, M., & Emekdaş, B. (2025). A Psychometric Evaluation of the Hypoglycemia Problem-Solving Scale (HPSS) in Turkish Older Adults with Diabetes. Healthcare, 13(9), 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13090997