Exploring the Gender Preferences for Healthcare Providers and Their Influence on Patient Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method and Materials

2.1. Theoretical Framework

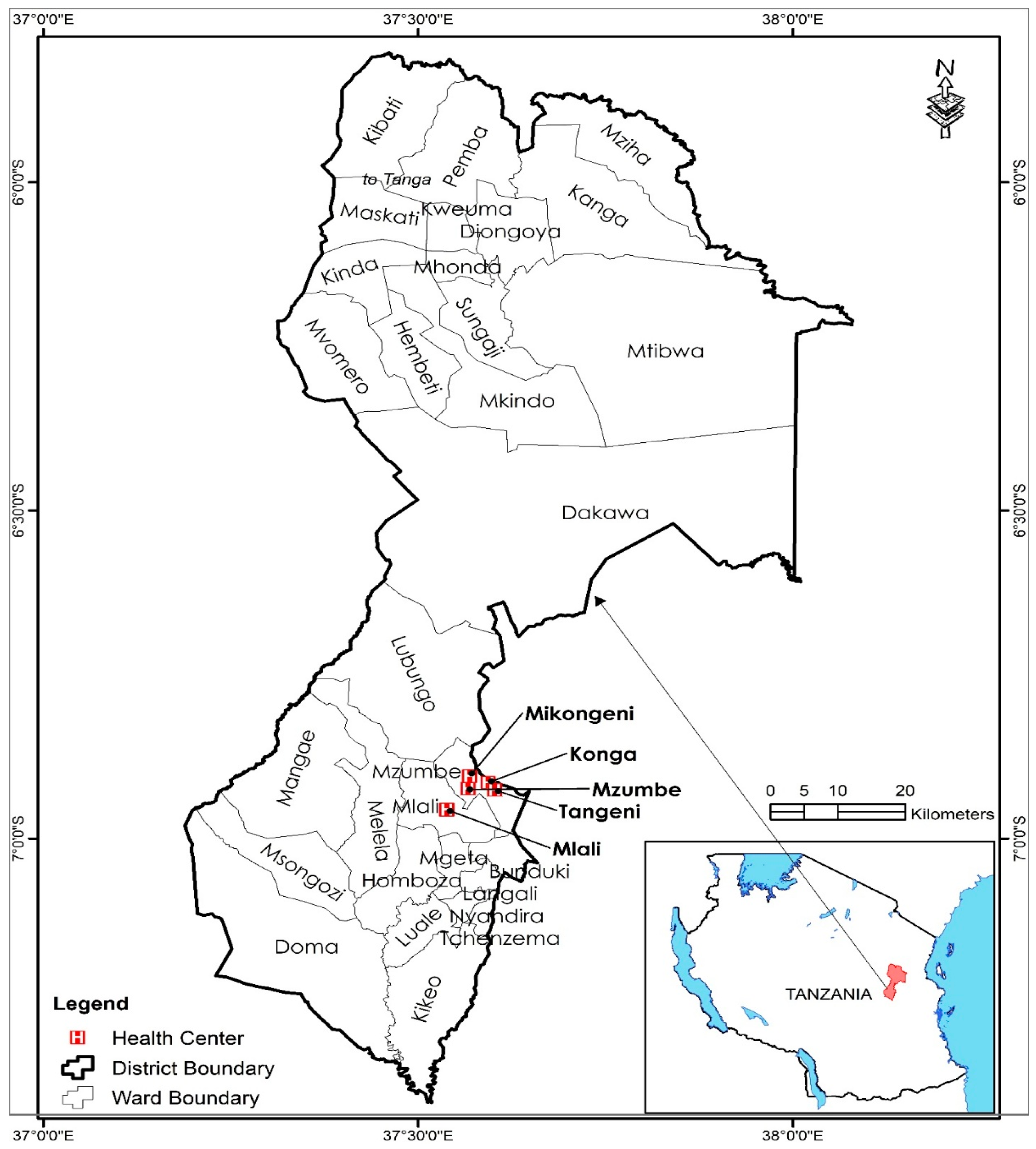

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Analytical Procedure

2.3.1. Modeling Gender Preferences

2.3.2. Modeling Patient Satisfaction

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Determinants of Patients’ Preferences for Gender of Health Provider

3.3. Effect of Patient Care Factors on Patient Satisfaction

3.4. Effect of Gender Preferences on Patient Satisfaction

4. Discussion

Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Worafi, Y.M. Quality of Healthcare Systems in Developing Countries: Status and Future Recommendations. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masic, I. Public Health Aspects of Global Population Health and Well-being in the 21st Century Regarding Determinants of Health. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderwick, H.; Hutchings, A.; Briggs, A.; Mays, N. The Impacts of Collaboration between Local Health Care and Non-Health Care Organizations and Factors Shaping How They Work: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassen, B. Prevention Umbrella: Health Protection, Health Promotion, and Disease Prevention. In Nursing: Health Education and Improving Patient Self-Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of Vaccination to Improved Survival and Health: Modelling 50 Years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isasi, F.; Naylor, M.D.; Skorton, D.; Grabowski, D.C.; Hernández, S.; Rice, V.M. Patients, Families, and Communities COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs. NAM Perspect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Carrigan, A.; Clay-Williams, R.; Hibbert, P.D.; Mahmoud, Z.; Pomare, C.; Pulido, D.F.; Meulenbroeks, I.; Knaggs, G.T.; E Austin, E.; et al. Innovative Models of Healthcare Delivery: An Umbrella Review of Reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkiya, S.H. Quality Communication Can Improve Patient-Centred Health Outcomes Among Older Patients: A Rapid Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, C.; Ballinger, C.; Nutbeam, D.; Adams, J. The Importance of Building Trust and Tailoring Interactions When Meeting Older Adults’ Health Literacy Needs. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2428–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opland, C.; Torrico, T.J. Psychotherapy and Therapeutic Relationship; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.statpearls.com/SocialWorker/ce/activity/114939 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Topley, M. The Art of Leadership Communication: Transparency, Listening, and Effective Feedback. BDJ Pract. 2023, 36, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindl, S.R.; Matos, M.; Dimaggio, G. The Interplay between Therapeutic Relationship and Therapeutic Technique: The Whole Is More Than the Sum of Its Parts. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 79, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balser, J.; Ryu, J.; Hood, M.; Kaplan, G.; Perlin, J.; Siegel, B. Care Systems COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs. NAM Perspect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eton, D.T.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Linzer, M.; Boehm, D.H.; A Rogers, E.; Yost, K.J.; Rutten, L.J.F.; Sauver, J.L.S.; Poplau, S.; Anderson, R.T. Healthcare Provider Relational Quality Is Associated with Better Self-Management and Less Treatment Burden in People with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. A Review on Factors Related to Patient Comfort Experience in Hospitals. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, T.S.; Berry, L.L.; Howard, C.; Moore, S.G.; Attai, D.J. Improving How Clinicians Communicate with Patients: An Integrative Review and Framework. J. Serv. Res. 2023, 26, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, S.P.; Hänggi, R.; Bussmann, Y.; Lörwald, A. A Model of Contributors to a Trusting Patient-Physician Relationship: A Critical Review Using a Systematic Search Strategy. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havana, T.; Kuha, S.; Laukka, E.; Kanste, O. Patients’ Experiences of Patient-Centred Care in Hospital Setting: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2023, 37, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickley, B.; Williams, L.T.; Morgan, M.; Ross, A.; Trigger, K.; Ball, L. Patient-Centred Care Delivered by General Practitioners: A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences and Perceptions of Patients and Providers. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2022, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, M.; Klein, K.; Sayers, K.; Valentino, J.; Leonardi, C.; Bronstone, A.; Wiseman, P.M.; Dasa, V. Objective Data Reveals Gender Preferences for Patients’ Primary Care Physician. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720967221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y. Cross-Cultural Consumer Behavior. In Consumer Behavior in Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, S.; Taylor, M.; Makusha, T.; Mabaso, M. Intersectionality of cultural norms and sexual behaviours: A qualitative study of young Black male students at a university in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Z.S.; Liamputtong, P. Cultural Determinants of Health, Cross-Cultural Research and Global Public Health. In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meranius, M.S.; Holmström, I.K.; Håkansson, J.; Breitholtz, A.; Moniri, F.; Skogevall, S.; Skoglund, K.; Rasoal, D. Paradoxes of person-centred care: A discussion paper. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, A.; Koffler, S.; Hashiloni-Dolev, Y. Feminism, gender medicine and beyond: A feminist analysis of “gender medicine”. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R. Traditional gender roles and patriarchal values: Critical personal narratives of a woman from the Chaoshan region in China. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2023, 180, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, M.G.; Biermann, M.C.; de Melo Maia, L.F.; de Oliveira Meneses, G. Structural Patriarchy and Male Dominance Hierarchies. In Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceneaux, C.L. The Struggle for Inclusion: Patriarchy Confronts Women and the LGBTQ+ Community. In Political Struggle in Latin America: Emerging Globalities and Civilizational Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Ming, L.C. Healthcare Systems in Developing Countries. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, E.; Millet, N.; Baron, A.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Doyle, D.M. Unequal geographies of gender-affirming care: A comparative typology of trans-specific healthcare systems across Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 356, 117145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulenova, A.; Rice, K.; Adams, A.; Lencucha, R. “We have to look deeper into why”: Perspectives on problem identification and prioritization of women’s and girls’ health across United Nations agencies. Glob. Health 2024, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlitz, A.; Hönig, I.; Hedebrant, K.; Asperholm, M. A Systematic Review and New Analyses of the Gender-Equality Paradox. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 17456916231202685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.A. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1995, 152, 1423–1433. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1337906/?page=2#supplementary-material1 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Platt, J.E.; Anthony, D.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Lee, S.D. What Does “Patient-Centered” Mean? Qualitative Perspectives from Older Adults and Family Caregivers. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211017608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Dunn, S.; Foster, A.; Grace, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Khanlou, N.; A Miller, F.; E Stewart, D.; Vigod, S.; Wright, F.C. How is patient-centred care addressed in women’s health? A theoretical rapid review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Nyhof, B.B.; Dunn, S.; Grace, S.L.; Green, C.; Stewart, D.E.; Wright, F.C. How is patient-centred care conceptualized in women’s health: A scoping review. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janerka, C.; Leslie, G.D.; Gill, F.J. Development of patient-centred care in acute hospital settings: A meta-narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 140, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, S.M.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L.M. Physician’s gender, communication style, patient preferences and patient satisfaction in gynecology and obstetrics: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 89, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.; Chew, S.; McCarthy, I.; Dawson, J.; Dixon-Woods, M. Encouraging openness in health care: Policy and practice implications of a mixed-methods study in the English National Health Service. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2023, 28, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghout, M.; van Exel, J.; Leensvaart, L.; Cramm, J.M. Healthcare professionals’ views on patient-centered care in hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickley, B.; Williams, L.T.; Morgan, M.; Ross, A.; Trigger, K.; Ball, L. Putting patients first: Development of a patient advocate and general practitioner-informed model of patient-centred care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Social role theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L.; Correll, S.J. Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gend. Soc. 2004, 18, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, W.H. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Eagly, A.H. Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Olson, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 46, pp. 55–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasoju, N.; Remya, N.S.; Sasi, R.; Sujesh, S.; Soman, B.; Kesavadas, C.; Muraleedharan, C.V.; Varma, P.R.H.; Behari, S. Digital health: Trends, opportunities and challenges in medical devices, pharma and bio-technology. CSI Trans. ICT 2023, 11, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennedey, V.; Hower, K.I.; Hillen, H.; Ansmann, L.; Kuntz, L.; Stock, S. Cologne Research and Development network (CoRe-net). Patients’ perspectives of facilitators and barriers to patient-centred care: Insights from qualitative patient interviews. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Okatta, A.U.; Amaechi, E.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Ezeh, C.P.; Elendu, I.D. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, N.C.; Campbell, D.G.; Caringi, J. A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers’ views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukappa, S.; Mudiyi, P.; Suresh, S.; Abdalla, W.; Subbarao, C. Evaluation of Challenges for Adoption of Smart Healthcare Strategies. Smart Health 2022, 26, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Buback, L.; Kelly, A.M.; Kirumbi, L.; Cohen, C.R.; Lyndon, A. Providers’ Perceptions of Communication and Women’s Autonomy During Childbirth: A Mixed Methods Study in Kenya. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshti, A.; Arashlow, F.T.; Fata, L.; Barzkar, F.; Baradaran, H.R. The Relationship Between Empathy and Listening Styles is Complex: Implications for Doctors in Training. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlakhan, J.U.; Foster, A.M.; Grace, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Stewart, D.E.; Gagliardi, A.R. What Constitutes Patient-Centred Care for Women: A Theoretical Rapid Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Holvoet, C. The Emergence of Empathy: A Developmental Neuroscience Perspective. Dev. Rev. 2021, 62, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, C.; Uğurluoğlu, Ö. The Effects of Patient-Centered Communication on Patient Engagement, Health-Related Quality of Life, Service Quality Perception and Patient Satisfaction in Patients with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study in Türkiye. Cancer Control 2024, 31, 10732748241236327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, L.; Li, Y.; Ding, D.; Wu, Q.; Liu, C.; Jiao, M.; Hao, Y.; Han, Y.; Gao, L.; Hao, J.; et al. Patient Satisfaction with Hospital Inpatient Care: Effects of Trust, Medical Insurance, and Perceived Quality of Care. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.J. High Medical Cost Burdens, Patient Trust, and Perceived Quality of Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shure, G.; Gamachu, M.; Mitiku, H.; Deressa, A.; Eyeberu, A.; Mohammed, F.; Zakaria, H.F.; Ayana, G.M.; Birhanu, A.; Debella, A.; et al. Patient Satisfaction and Associated Factors Among Insured and Uninsured Patients in Deder General Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: A Facility-Based Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1259840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Mihan, R.; Mousavi, S.Z.; Reniers, R.L.; Bateni, F.S.; Alikhani, R.; Mousavi, S.B. A Narrative Review of Stigma Related to Infectious Disease Outbreaks: What Can Be Learned in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 565919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moges, S.; Lajore, B.A. Mortality and Associated Factors Among Patients with TB-HIV Co-infection in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, E.; Sommerland, N.; Masquillier, C.; Rau, A.; Engelbrecht, M.; Van Rensburg, A.J.; Kigozi, G.; Ponnet, K.; Van Damme, W. Unpacking the Dynamics of Double Stigma: How the HIV-TB Co-epidemic Alters TB Stigma and Its Management Among Healthcare Workers. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyblade, L.; Stockton, M.A.; Giger, K.; Bond, V.; Ekstrand, M.L.; Lean, R.M.; Mitchell, E.M.H.; Nelson, R.E.; Sapag, J.C.; Siraprapasiri, T.; et al. Stigma in Health Facilities: Why It Matters and How We Can Change It. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascayano, F.; Toso-Salman, J.; Ho, Y.C.S.; Dev, S.; Tapia, T.; Thornicroft, G.; Cabassa, L.J.; Khenti, A.; Sapag, J.; Bobbili, S.J.; et al. Including Culture in Programs to Reduce Stigma Toward People with Mental Disorders in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 57, 140–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Ko, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Chueh, J.W.; Chen, P.Y.; Cooper, C.L. Patient Safety and Staff Well-Being: Organizational Culture as a Resource. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Silva, R.; Balakrishnan, J.M.; Bari, T.; Verma, R.; Kamath, R. Unveiling the Heartbeat of Healing: Exploring Organizational Culture in a Tertiary Hospital’s Emergency Medicine Department and Its Influence on Employee Behavior and Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balay-odao, E.M.; Cruz, J.P.; Almazan, J.U. Consequences of the Hospital Nursing Research Culture: Perspective of Staff Nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2024, 11, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalamaw, A.; Khatri, R.B.; Erku, D.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Wolka, E.; Assefa, Y. Successes and Challenges Towards Improving Quality of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Wachira, J.; Kafu, C.; Braitstein, P.; Wilson, I.B.; Harrison, A.; Owino, R.; Akinyi, J.; Koech, B.; Genberg, B. The Role of Gender in Patient-Provider Relationships: A Qualitative Analysis of HIV Care Providers in Western Kenya with Implications for Retention in Care. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C. Patient satisfaction and gender composition of physicians—A cross-sectional study of community health services in Hubei, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldt, C.A.; Keiner, D.; Best, N.; Bertsche, T. Attitudes and Experiences of Patients Regarding Gender-Specific Aspects of Pain Management. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Naidoo, P.; Armoogum, S. Navigating the Challenges of Female Leadership in the Information and Communication Technology and Engineering Sectors. J. Bus. Socio-Econ. Dev. 2025, 5, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain Uzir, M.; Jerin, I.; Al Halbusi, H.; Abdul Hamid, A.B.; Abdul Latiff, A.S. Does Quality Stimulate Customer Satisfaction Where Perceived Value Mediates and the Usage of Social Media Moderates? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirera, B.; Naanyu, V.; Kussin, P.; Lagat, D. Impact of Patient-Centered Communication on Patient Satisfaction Scores in Patients with Chronic Life-Limiting Illnesses: An Experience from Kenya. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1290907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, M.B.; Erondu, A.I.; Smith, N.A.; Peek, M.E.; Woodruff, J.N.; Chin, M.H. Eliminating Explicit and Implicit Biases in Health Care: Evidence and Research Needs. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masibo, R.M.; Masika, G.M.; Kibusi, S.M. Gender Stereotypes and Bias in Nursing: A Qualitative Study in Tanzania. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhomayani, K.M.; Bukhary, H.; Aljuaid, F.; A Alotaibi, T.; Alqurashi, F.S.; Althobaiti, K.; Althobaiti, N.S.; Althomali, O.Y.; Althobaiti, A.; Aljuaid, M.M.; et al. Gender Preferences in Healthcare: A Study of Saudi Patients’ Physician Preferences. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2025, 19, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikweyiya, Y.; Addo-Lartey, A.A.; Alangea, D.O.; Dako-Gyeke, P.; Chirwa, E.D.; Coker-Appiah, D.; Adanu, R.M.K.; Jewkes, R. Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 100 | 41.70% |

| Female | 140 | 58.30% | |

| Age group | 18–25 years | 40 | 16.70% |

| 26–35 years | 72 | 30.00% | |

| 36–45 years | 60 | 25.00% | |

| 46–55 years | 45 | 18.80% | |

| Above 55 years | 23 | 9.60% | |

| Education level | No formal education | 20 | 8.30% |

| Primary education | 82 | 34.20% | |

| Secondary education | 84 | 35.00% | |

| Tertiary education | 54 | 22.50% | |

| Marital status | Single | 92 | 38.30% |

| Married | 120 | 50.00% | |

| Divorced/separated | 18 | 7.50% | |

| Widowed | 10 | 4.20% | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 100 | 41.70% |

| Business owner | 60 | 25.00% | |

| Salaried worker | 50 | 20.80% | |

| Unemployed | 30 | 12.50% | |

| Religion | Christian | 140 | 58.30% |

| Muslim | 90 | 37.50% | |

| Other | 10 | 4.20% | |

| Healthcare facility visited | Mikongeni Health Centre | 50 | 20.80% |

| Mzumbe Health Centre | 50 | 20.80% | |

| Konga Health Centre | 45 | 18.80% | |

| Tangeni Mission Health Centre | 55 | 22.90% | |

| Mlali Health Centre | 40 | 16.70% | |

| Health provider gender preference | Male | 101 | 42.08% |

| Female | 74 | 30.83% | |

| Both male and female | 65 | 27.08% |

| Differences Across Gender Preferences | Overall Response | Responses Based on Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Comfort with Intimate Care | Males treat by comfort with intimate care | 80 (33.30%) | 50 (20.80%) | 30 (12.50%) |

| Females treat by comfort with intimate care | 120 (50.00%) | 30 (12.50%) | 90 (37.50%) | |

| Both males and females treat by comfort | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Cultural or Religious Norms | Males are more cultural and religious | 90 (37.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | 40 (16.70%) |

| Females are more cultural and religious | 100 (41.70%) | 30 (12.50%) | 70 (29.20%) | |

| Both males and females are cultural and religious | 50 (20.80%) | 20 (8.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | |

| Perceived Empathy | Males are more empathetic | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) |

| Females are more empathetic | 140 (58.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 110 (45.80%) | |

| Both males and females are empathetic | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Perceived Professionalism | Males are more professional | 110 (45.80%) | 64 (26.70%) | 46 (19.20%) |

| Females are more professional | 90 (37.50%) | 30 (12.50%) | 60 (25.00%) | |

| Both males and females are professional | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Good Communication Approach | Males have good communication approach | 80 (33.30%) | 50 (20.80%) | 30 (12.50%) |

| Females have good communication approach | 120 (50.00%) | 30 (12.50%) | 90 (37.50%) | |

| Both males and females have good communication | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Reliability to Patients | Males are more reliable to patients | 100 (41.70%) | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) |

| Females are more reliable to patients | 110 (45.80%) | 30 (12.50%) | 80 (33.30%) | |

| Both males and females are reliable | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) | |

| Privacy and Modesty of Patients | Males prioritize privacy and modesty | 70 (29.20%) | 50 (20.80%) | 20 (8.30%) |

| Females prioritize privacy and modesty | 140 (58.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 110 (45.80%) | |

| Both males and females prioritize privacy | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) | |

| Stereotypes about Competence | Males are more competent | 120 (50.00%) | 64 (26.70%) | 56 (23.30%) |

| Females are more competent | 80 (33.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Both males and females are competent | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Fairness and Judgement | Males are fair and critical in judgement | 90 (37.50%) | 60 (25.00%) | 30 (12.50%) |

| Females are fair and critical in judgement | 110 (45.80%) | 30 (12.50%) | 80 (33.30%) | |

| Both males and females are critical | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Health Issue-Specific Concerns | Males are good for critical health issues | 110 (45.80%) | 60 (25.00%) | 50 (20.80%) |

| Females are good for critical health issues | 100 (41.70%) | 30 (12.50%) | 70 (29.20%) | |

| Both males and females are good for issues | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) | |

| Surgery Ability | Males are good in surgery | 120 (50.00%) | 64 (26.70%) | 56 (23.30%) |

| Females are good in surgery | 80 (33.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Both males and females are good in surgery | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Health Providers | Differences Across Gender | Overall Response | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical staff | Males are better medical doctors | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) |

| Females are better medical doctors | 50 (20.80%) | 15 (6.30%) | 35 (14.60%) | |

| Both males and females are better medical doctors | 160 (66.70%) | 80 (33.30%) | 80 (33.30%) | |

| Males are better nurses | 20 (8.30%) | 15 (6.30%) | 5 (2.10%) | |

| Females are better nurses | 100 (41.70%) | 40 (16.70%) | 60 (25.00%) | |

| Both males and females are better nurses | 120 (50.00%) | 65 (27.10%) | 55 (22.90%) | |

| Males are better pharmacists | 40 (16.70%) | 25 (10.40%) | 15 (6.30%) | |

| Females are better pharmacists | 80 (33.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Both males and females are better pharmacists | 120 (50.00%) | 60 (25.00%) | 60 (25.00%) | |

| Administrative staff | Males are better health administrators | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) |

| Females are better health administrators | 80 (33.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Both males and females are better health administrators | 100 (41.70%) | 50 (20.80%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Males are better receptionists and front desk officers | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) | |

| Females are better receptionists and front desk officers | 120 (50.00%) | 50 (20.80%) | 70 (29.20%) | |

| Both males and females are better receptionists and front desk officers | 90 (37.50%) | 45 (18.80%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Males are better at record keeping | 40 (16.70%) | 30 (12.50%) | 10 (4.20%) | |

| Females are better at record keeping | 110 (45.80%) | 45 (18.80%) | 65 (27.10%) | |

| Both males and females are better at record keeping | 90 (37.50%) | 45 (18.80%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Specialized roles | Males are better therapists | 50 (20.80%) | 35 (14.60%) | 15 (6.30%) |

| Females are better therapists | 100 (41.70%) | 40 (16.70%) | 60 (25.00%) | |

| Both males and females are better therapists | 90 (37.50%) | 45 (18.80%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Males are better emergency medical technicians (EMTs) | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) | |

| Females are better emergency medical technicians (EMTs) | 80 (33.30%) | 35 (14.60%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Both males and females are better emergency medical technicians (EMTs) | 100 (41.70%) | 50 (20.80%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Males are better mental health professionals | 40 (16.70%) | 25 (10.40%) | 15 (6.30%) | |

| Females are better mental health professionals | 90 (37.50%) | 35 (14.60%) | 55 (22.90%) | |

| Both males and females are better mental health professionals | 110 (45.80%) | 55 (22.90%) | 55 (22.90%) | |

| Technical staff | Males are better in medical labs | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) | 20 (8.30%) |

| Females are better in medical labs | 80 (33.30%) | 35 (14.60%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Both males and females are better in medical labs | 100 (41.70%) | 50 (20.80%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Males are better radiologists | 50 (20.80%) | 35 (14.60%) | 15 (6.30%) | |

| Females are better radiologists | 70 (29.20%) | 30 (12.50%) | 40 (16.70%) | |

| Both males and females are better radiologists | 120 (50.00%) | 60 (25.00%) | 60 (25.00%) | |

| Support staff | Males are better housekeepers | 30 (12.50%) | 20 (8.30%) | 10 (4.20%) |

| Females are better housekeepers | 150 (62.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | 100 (41.70%) | |

| Both males and females are better housekeepers | 60 (25.00%) | 30 (12.50%) | 30 (12.50%) | |

| Males are better in maintenance | 100 (41.70%) | 60 (25.00%) | 40 (16.70%) | |

| Females are better in maintenance | 50 (20.80%) | 20 (8.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | |

| Both males and females are better in maintenance | 90 (37.50%) | 45 (18.80%) | 45 (18.80%) | |

| Males are better in security | 130 (54.20%) | 80 (33.30%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Females are better in security | 40 (16.70%) | 15 (6.30%) | 25 (10.40%) | |

| Both males and females are better in security | 70 (29.20%) | 35 (14.60%) | 35 (14.60%) | |

| Information technology (IT) and health informatics | Males are better in IT and health informatics | 100 (41.70%) | 70 (29.20%) | 30 (12.50%) |

| Females are better in IT and health informatics | 80 (33.30%) | 30 (12.50%) | 50 (20.80%) | |

| Both males and females are better in IT and health informatics | 60 (25.00%) | 30 (12.50%) | 30 (12.50%) |

| Patient Care Factors | Male | Female | Both Male and Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort with Intimate Care | 4.11 (0.80) | 4.50 (0.70) | 4.30 (0.6) |

| Cultural or Religious Norms | 3.80 (1.00) | 4.20 (0.90) | 4.00 (0.80) |

| Perceived Empathy | 4.00 (0.90) | 4.40 (0.80) | 4.20 (0.70) |

| Perceived Professionalism | 4.30 (0.60) | 4.60 (0.50) | 4.50 (0.50) |

| Good Communication Approach | 4.20 (0.70) | 4.50 (0.60) | 4.40 (0.60) |

| Reliability to Patients | 4.11 (0.80) | 4.30 (0.70) | 4.20 (0.70) |

| Privacy and Modesty of Patients | 4.00 (0.90) | 4.50 (0.70) | 4.30 (0.70) |

| Stereotypes about Competence | 3.90 (1.00) | 4.30 (0.80) | 4.21 (0.90) |

| Fairness and Judgement | 4.10 (0.80) | 4.40 (0.70) | 4.30 (0.70) |

| Health Issue-Specific Concerns | 3.80 (1.00) | 4.20 (0.90) | 4.00 (0.80) |

| Surgery Ability | 4.20 (0.70) | 4.40 (0.60) | 4.30 (0.60) |

| Gender Preferences | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Both (Males and Females) | |

| Female patient head of household | 0.45 * (0.12) | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.11) |

| Sex of patient (female) | 0.60 ** (0.14) | 0.10 (0.18) | 0.18 (0.13) |

| Patient household size | −0.10 (0.23) | −0.08 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.06) |

| Patient income | 0.20 * (0.07) | 0.35 ** (0.08) | 0.15 (0.05) |

| Medical consultation fee | −0.15 ** (0.02) | −0.27 (0.23) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Insured patient | 0.65 *** (0.13) | 0.29 * (0.10) | 0.40 ** (0.12) |

| Patient Occupation (ref: unemployed) | |||

| Farmer | 0.38 ** (0.10) | 0.16 * (0.07) | 0.13 * (0.05) |

| Business owner | 0.49 *** (0.01) | 0.05 (0.13) | 0.19 * (0.09) |

| Salaried worker | 0.70 *** (0.12) | 0.14 * (0.04) | 0.45 ** (0.09) |

| Patient Religion (ref: other religion) | |||

| Christian | 0.50 ** (0.12) | 0.70 *** (0.10) | 0.40 ** (0.09) |

| Muslim | 0.35 (0.09) | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.25 (0.18) |

| Patient-visited health centers (ref: Mlali Health Centre) | |||

| Mikongeni Health Centre | 0.40 ** (0.10) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| Mzumbe Health Centre | 0.45 ** (0.11) | 0.15 ** (0.03) | 0.09 ** (0.01) |

| Konga Health Centre | 0.50 (0.12) | 0.70 (0.14) | 0.40 (0.11) |

| Tangeni Mission Health Centre | 0.37 *** (0.03) | 0.80 *** (0.15) | 0.45 ** (0.12) |

| Patient education (ref: no formal education) | |||

| Primary education | 0.35 ** (0.08) | −0.55 *** (0.10) | 0.30 (0.27) |

| Secondary education | 0.45 ** (0.09) | 0.15 * (0.06) | 0.05 (0.08) |

| Tertiary education | 0.70 ** (0.10) | 0.54 *** (0.12) | 0.20 ** (0.09) |

| Patient marital status (ref: widowed) | |||

| Single | 0.40 *** (0.00) | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.30 (0.09) |

| Married | 0.27 * (0.11) | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.10) |

| Divorced/separated | 0.30 (0.20) | 0.50 (0.31) | 0.25 (0.28) |

| Patient age (ref: above 55 years) | |||

| 18–25 years | 0.47 *** (0.08) | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.15 (0.27) |

| 26–35 years | 0.35 *** (0.09) | 0.15 * (0.06) | 0.09 * (0.01) |

| 36–45 years | 0.50 (0.10) | 0.70 (0.12) | 0.35 (0.09) |

| 46–55 years | 0.40 (0.10) | 0.60 (0.12) | 0.30 (0.09) |

| Patient diseases (ref: non-infectious diseases—hereditary) | |||

| Infectious diseases | 0.88 *** (0.03) | 0.29 * (0.11) | 0.20 (0.12) |

| Non-infectious diseases | 0.40 ** (0.19) | 0.29 ** (0.08) | 0.35 * (0.11) |

| . | Very High Satisfaction | High Satisfaction | Low Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort with Intimate Care | 0.45 * (0.20) | 0.35 (0.28) | −0.20 (0.17) |

| Cultural or Religious Norms | 0.50 (0.32) | 0.40 (0.29) | 0.25 (0.16) |

| Perceived Empathy | 0.60 *** (0.10) | 0.48 ** (0.21) | −0.30 * (0.14) |

| Perceived Professionalism | 0.75 *** (0.14) | 0.45 ** (0.11) | −0.40 * (0.17) |

| Good Communication Approach | 0.70 *** (0.12) | 0.25 * (0.09) | −0.25 (0.14) |

| Reliability to Patients | 0.53 *** (0.19) | 0.19 * (0.09) | −0.30 (0.23) |

| Privacy and Modesty of Patients | 0.25 *** (0.03) | 0.10 ** (0.03) | −0.35 (0.22) |

| Stereotypes about Competence | 0.40 (0.28) | 0.30 (0.18) | −0.20 (0.23) |

| Fairness and Judgement | 0.22 (0.15) | 0.23 (0.19) | −0.25 (0.18) |

| Health Issue-Specific Concerns | 0.50 (0.42) | 0.35 (0.19) | −0.30 (0.21) |

| Surgery Ability | 0.60 *** (0.10) | 0.24 * (0.10) | −0.06 * (0.01) |

| Comfort with Intimate Care*Male | 0.30 ** (0.09) | 0.15 * (0.07) | 0.01 (0.08) |

| Cultural or Religious Norms*Male | 0.35 (0.10) | 0.30 (0.38) | 0.20 (0.39) |

| Perceived Empathy*Male | 0.40 *** (0.01) | 0.34 (0.29) | 0.05 (0.26) |

| Perceived Professionalism*Male | 0.86 *** (0.12) | 0.45 ** (0.10) | −0.30 ** (0.09) |

| Good Communication Approach*Male | 0.45 (0.30) | 0.40 (0.26) | 0.05 (0.08) |

| Reliability to Patients*Male | 0.40 (0.29) | 0.35 (0.39) | 0.20 (0.19) |

| Privacy and Modesty of Patients*Male | 0.50 *** (0.12) | 0.40 ** (0.10) | 0.14 (0.11) |

| Stereotypes about Competence*Male | 0.30 *** (0.00) | 0.25 ** (0.08) | 0.15 (0.08) |

| Fairness and Judgement*Male | 0.40 (0.22) | 0.35 (0.19) | 0.05 (0.10) |

| Health Issue-Specific Concerns*Male | 0.35 ** (0.11) | 0.30 (0.16) | 0.07 (0.10) |

| Surgery Ability*Male | 0.40 ** (0.12) | 0.35 (0.17) | 0.22 (0.18) |

| Comfort with Intimate Care*Female | 0.50 *** (0.13) | 0.40 ** (0.10) | −0.35 ** (0.12) |

| Cultural or Religious Norms*Female | 0.55 (0.44) | 0.45 (0.31) | −0.40 (0.23) |

| Perceived Empathy*Female | 0.60 *** (0.15) | 0.50 ** (0.12) | 0.02 (0.17) |

| Perceived Professionalism*Female | −0.17 ** (0.04) | −0.08 * (0.02) | 0.13 (0.10) |

| Good Communication Approach*Female | −0.60 *** (0.14) | −0.50 ** (0.11) | 0.45 (0.23) |

| Reliability to Patients*Female | −0.57 ** (0.13) | −0.08 (0.10) | 0.40 (0.32) |

| Privacy and Modesty of Patients*Female | 0.25 (0.15) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.07 (0.14) |

| Stereotypes about Competence*Female | −0.40 ** (0.11) | −0.30 ** (0.09) | 0.04 (0.10) |

| Fairness and Judgement*Female | −0.32 (0.12) | −0.26 (0.10) | 0.19 (0.11) |

| Health Issue-Specific Concerns*Female | −0.45 * (0.20) | −0.35 (0.27) | 0.15 (0.19) |

| Surgery Ability*Female | −0.55 * (0.23) | −0.45 * (0.21) | 0.36 (0.22) |

| Patient demographic controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Very High Satisfaction | High Satisfaction | Low Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender preference (ref: both male and female) | |||

| Male | 0.84 *** (0.02) | 0.47 ** (0.10) | −0.35 *** (0.01) |

| Female | 0.23 * (0.09) | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.10) |

| Medical consultation fee | −0.26 *** (0.02) | −0.13 ** (0.02) | 0.24 *** (0.02) |

| Insured patient | 0.32 ** (0.13) | 0.28 ** (0.08) | −0.30 * (0.12) |

| Patient diseases (ref: non-infectious diseases—hereditary) | |||

| Infectious diseases | −0.60 ** (0.24) | −0.50 * (0.22) | 0.08 (0.13) |

| Non-infectious diseases (lifestyle) | 0.20 * (0.09) | 0.16 (0.11) | −0.07 (0.11) |

| Patient visited health centres (ref: Mlali Health Centre) | |||

| Mikongeni Health Centre | −0.24 (0.13) | −0.18 (0.10) | 0.35 (0.21) |

| Mzumbe Health Centre | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.45 * (0.21) | −0.40 (0.12) |

| Konga Health Centre | −0.06 (0.14) | −0.13 (0.10) | 0.41 (0.22) |

| Tangeni Mission Health Centre | 0.70 *** (0.15) | 0.55 ** (0.13) | −0.04 (0.14) |

| Patient demographic controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Patient care factors control | No | No | No |

| Observations | 240 | ||

| LR Chi squared (12) | 37.08 | ||

| Prob > Chi squared | 48.13 | ||

| Pseudo R squared | 0.3564 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitole, F.A.; Ali, Z.; Song, J.; Ali, M.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Heidler, P.; Yahya, M.A.; Shahid, M. Exploring the Gender Preferences for Healthcare Providers and Their Influence on Patient Satisfaction. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091063

Kitole FA, Ali Z, Song J, Ali M, Fahlevi M, Aljuaid M, Heidler P, Yahya MA, Shahid M. Exploring the Gender Preferences for Healthcare Providers and Their Influence on Patient Satisfaction. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091063

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitole, Felician Andrew, Zaiba Ali, Jiayi Song, Muhammad Ali, Mochammad Fahlevi, Mohammed Aljuaid, Petra Heidler, Muhammad Ali Yahya, and Muhammad Shahid. 2025. "Exploring the Gender Preferences for Healthcare Providers and Their Influence on Patient Satisfaction" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091063

APA StyleKitole, F. A., Ali, Z., Song, J., Ali, M., Fahlevi, M., Aljuaid, M., Heidler, P., Yahya, M. A., & Shahid, M. (2025). Exploring the Gender Preferences for Healthcare Providers and Their Influence on Patient Satisfaction. Healthcare, 13(9), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091063