Lived Experience of Men with Prostate Cancer in Ireland: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

2.4. Data Collection Tool

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

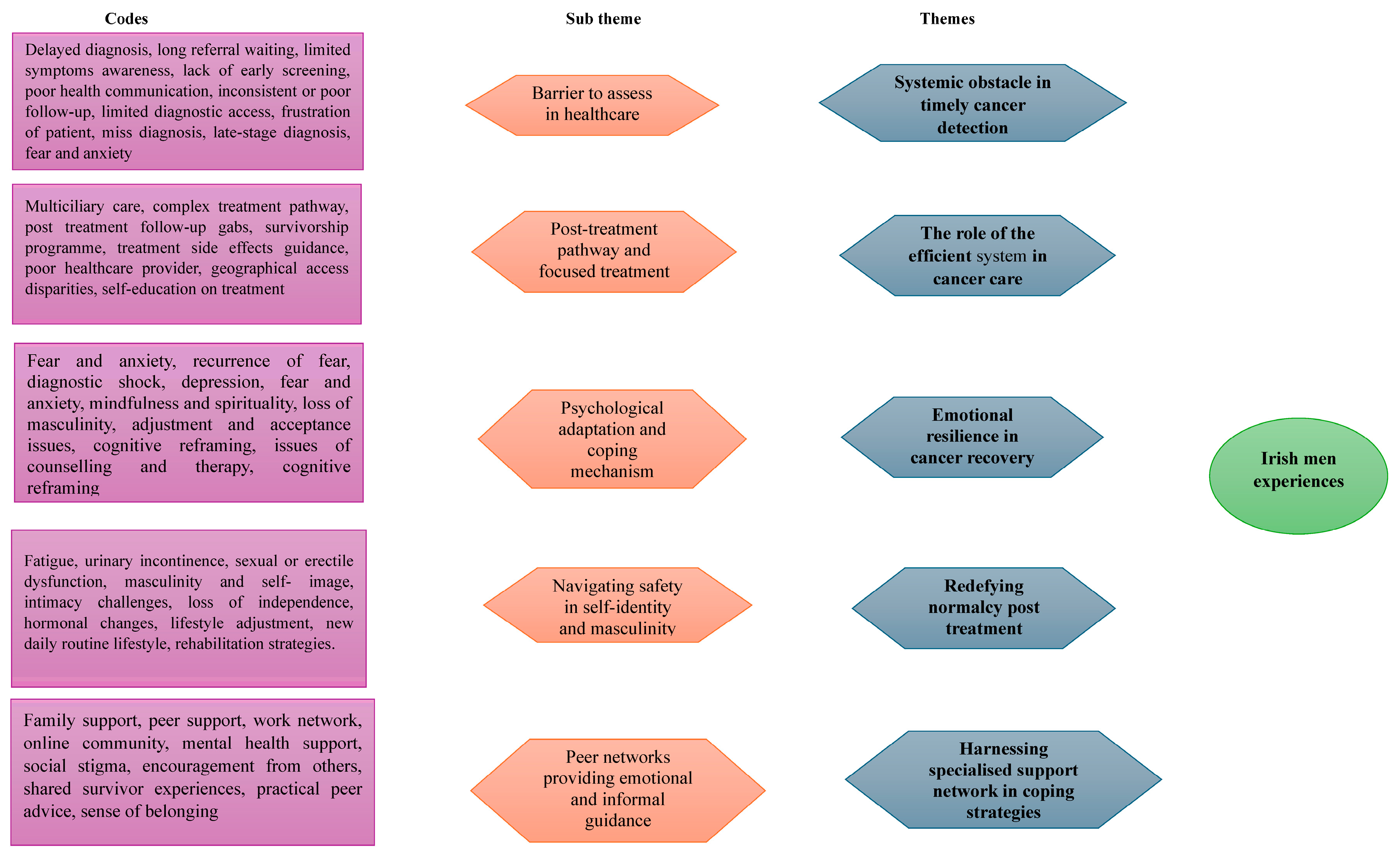

3.2. Themes Identified

3.3. Theme 1: Systemic Obstacle in Timely Cancer Detection

“I rang (named hospital), and I said, would you ever ring (named other hospital) and tell them to hurry up? …. and they said, oh we cannot …… it is between me and (named the other hospital)”.(p5)

“Nine months to get a biopsy ……. they should have noticed something sooner... they could have told me the biopsy can be done in a private place for a few hundred euros”.(p5)

“The waiting list was so long; …… it felt like forever before I got a diagnosis”(p6)

“I had symptoms for months, but getting a referral took ages”(p5)

3.4. Theme 2: The Role of the Efficient System in Cancer Care

“The doctors and nurses were excellent …. but I had to figure out post treatment care on my own”.(p3)

“There needs to be more multidisciplinary involvement (urologists, oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, specialist nurses, psychologists, physiotherapists, primary care physician) from the start”(p4)

3.5. Theme 3: Emotional Resilience in Cancer Recovery

“I did not expect it at all……. there is a lot of fear that hits all at once”(p6)

“How long will I live”.(p2)

“Eventually I found acceptance by focusing on the present and what I can control”(p5)

3.6. Theme 4: Redefining Normalcy Post Treatment

“My body just did not feel like my own for a long time”(p6)

“I have adjusted to a slower pace……things are just different now”(p5)

3.7. Theme 5: Harnessing Specialised Support Network in Coping Strategies

“I would not have coped as well without her (wife) constant encouragement”(p1)

“My old army buddies have been a pillar of strength through this”(p3)

“Connecting with others with similar situations gave me hope and practical advice”(p6)

”Attending veterans support group gave me a sense of belonging”(p6)

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Funds (WCRF 2024): Prostate Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/prostate-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Irish Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics: Irish Cancer Society 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.ie/cancer-information-and-support/cancer-information/about-cancer/cancer-statistics (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Pernar, C.H.; Ebot, E.M.; Pettersson, A.; Graff, R.E.; Giunchi, F.; Ahearn, T.U.; Gonzalez-Feliciano, A.G.; Markt, S.C.; Wilson, K.M.; Stopsack, K.H.; et al. A prospective study of the association between physical activity and risk of prostate cancer defined by clinical features and TMPRSS2: ERG. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chan, E.O.; Liu, X.; Lok, V.; Ngai, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; Chiu, P.K.; Vasdev, N.; et al. Global Trends of Prostate Cancer by Age, and Their Associations with Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Human Development Index (HDI), Smoking, and Alcohol Drinking. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2023, 21, e261–e270.e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, M.B.; Soerjomataram, I.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur. J. Urol. 2020, 77, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteduca, V.; Oromendia, C.; Eng, K.W.; Bareja, R.; Sigouros, M.; Molina, A.; Faltas, B.M.; Sboner, A.; Mosquera, J.M.; Elemento, O.; et al. Clinical features of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehal, A. Duodenal Metastasis from Colorectal Cancer: A Case Report. Saudi J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Psutka, S.P.; Etzioni, R. Personalized risks of over diagnosis for screen detected prostate cancer incorporating patient comorbidities: Estimation and communication. J. Urol. 2019, 202, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellakis, M.; Flores, L.J.; Ramachandran, S. Patterns of indolence in prostate cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N.J.; Souter, L.H.; Salami, S.S. A systematic review of family history, race/ethnicity, and genetic risk on prostate cancer detection and outcomes: Considerations in PSA-based screening. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 43, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozescu, T.; Popa, F. Prostate cancer between prognosis and adequate/proper therapy. J. Med. Life 2017, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gandaglia, G.; Albers, P.; Abrahamsson, P.A.; Briganti, A.; Catto, J.W.F.; Chapple, C.R.; Montorsi, F.; Mottet, N.; Roobol, M.J.; Sønksen, J.; et al. Structured population-based prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer: The European Associa-tion of Urology position in 2019. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Ebell, M.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Poppel, H.; Roobol, M.J.; Chapple, C.R.; Catto, J.W.; N’Dow, J.; Sønksen, J.; Stenzl, A.; Wirth, M. Prostate-specific antigen testing as part of a risk-adapted early detection strategy for prostate cancer: European Association of Urology position and recommendations for 2021. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, Z.; Sohrabivafa, M.; Momenabadi, V.; Moayed, L.; Goodarzi, E. Global cancer statistics 2018: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide prostate cancers and their relationship with the human development index. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2019, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish Cancer Society. Understanding Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Caring for People with Cancer. Ireland. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.ie/cancer-information-and-support/cancer-types/prostate-cancer (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- National Health Service. Overview: Prostate Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/prostate-cancer/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Baden, M.; Lu, L.; Drummond, F.J.; Gavin, A.; Sharp, L. Pain, fatigue and depression symptom cluster in survivors of prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4813–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Hui, J.M.; Liu, K.; Dee, E.C.; Ng, K.; Liu, T.; Tse, G.; Ng, C.F. Long-term prognostic impact of cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: A population-based competing risk analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, B.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, L. prostate cancer incidence and mortality: Global status and temporal trends in 89 countries from 2000 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 811044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, G.K.; Praharaj, P.P.; Kittaka, H.; Mridha, A.R.; Black, O.M.; Singh, R.; Mercer, R.; van Bokhoven, A.; Torkko, K.C.; Agarwal, C.; et al. Exosome proteomic analyses identify inflammatory phenotype and novel biomarkers in African American prostate cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergengren, O.; Pekala, K.R.; Matsoukas, K.; Fainberg, J.; Mungovan, S.F.; Bratt, O.; Bray, F.; Brawley, O.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Mucci, L.; et al. 2022 Update on prostate cancer epidemiology and risk factors: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernar, C.H.; Ebot, E.M.; Wilson, K.M.; Mucci, L.A. The epidemiology of prostate cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a030361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumuni, S.; O’Donnell, C.; Doody, O. The risk factors and screening uptake for prostate Cancer: A scoping review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods-Burnham, L.; Stiel, L.; Wilson, C.; Montgomery, S.; Durán, A.M.; Ruckle, H.R.; Thompson, R.A.; De León, M.; Casiano, C.A. Physician consultations, prostate cancer knowledge, and PSA screening of African American men in the era of shared decision-making. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceres, M.; Quinn, G.P.; Loscalzo, M.; Rice, D. Cancer screening considerations and cancer screening uptake for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 34, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.J.; Oladeru, O.T.; Wang, K.; Attwood, K.; Singh, A.K.; Haas-Kogan, D.A.; Neira, P.M. Prostate cancer screening patterns among sexual and gender minority individuals. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarva, E.; Oikarinen, A.; Andersson, J.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Kääriäinen, M.; Meriläinen, M.; Mikkonen, K. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of digital health competence: A qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Open. 2022, 9, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S. Saturation in qualitative research: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG). Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland (NMBI). The Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for Registered Nurses and Registered Midwives 2025. Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/Standards-Guidance/Code (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.C.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer—2020 update. Part 1: Screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society (ASC 2023). American Cancer Society Recommendation for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/prostate-cancer-screening-guidelines.html (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Centre for Disease Control Prevention (CDC2023). Should IGet Scanned for Prostate Cancer? C.D.C. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/prostate-cancer/screening/get-screened.html (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Merriel, S.W.; Seggie, A.; Ahmed, H. Diagnosis of prostate cancer in primary care: Navigating updated clinical guidance. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, 73, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, M.; Cheon, G.J. Multidisciplinary team approach in prostate-specific membrane antigen theranostics for prostate cancer: A narrative review. J. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 22, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Baquero, R.; Fernandez-Avila, C.M.; Alvarez-Ossorio, J.L. Functional results in the treatment of localized prostate cancer. An updated literature review. Rev. Int. Androl. 2019, 17, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, N.D.; Morgans, A.K.; El-Haddad, G.; Srinivas, S.; Abramowitz, M. Addressing challenges and controversies in the management of prostate cancer with multidisciplinary teams. Target. Oncol. 2022, 17, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord, E.; Flores, J.P.; Posielski, N.; Koenig, H.; Ho, O.; Porter, C. Patient reported outcomes and health related quality of life in localized prostate cancer: A review of current evidence. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, L.D.; Poulsen, M.H.; Jensen, M.E.; Lund, L.; Hildebrandt, M.G.; Nørgaard, B. Health-related quality of life the first year after a prostate cancer diagnosis a systematic review. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2023, 17, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Resende Izidoro, L.C.; Azevedo, C.; Pereira, M.G.; Chianca, T.C.; Borges, C.J.; de Almeida Cavalcante Oliveira, L.M.; da Mata, L.R.F. Effect of cognitive-behavioral program on quality of life in men with post-prostatectomy incontinence: A randomized trial. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2024, 58, e20240187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, V.S.; Falk, D.; Cheatham, C.; Cullen, J.; Hoehn, R. Patient navigation in cancer treatment: A systematic review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 504–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerot, C.D.; Bergerot, P.G.; Molina, L.N.; Freitas, A.N.; do Nascimento, K.L.; Philip, E.J.; Lee, D.; Sacchi, L.L.; Nazario, J.L.; Matos Neto, J.N.; et al. Impact of a biopsychosocial screening program on clinical and hospital-based outcomes in cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e822–e828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, H. Advancing Cancer Treatment with AI-Driven Personalized Medicine and Cloud-Based Data Integration. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 4, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumuni, S.; O’Donnell, C.; Doody, O. The Experiences and Perspectives of Persons with Prostate Cancer and Their Partners: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis Using Meta-Ethnography. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, J.; Butow, P.; Lai-Kwon, J.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rynderman, M.; Jefford, M. Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer. The Lancet 2022, 399, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalata, W.; Gothelf, I.; Bernstine, T.; Michlin, R.; Tourkey, L.; Shalata, S.; Yakobson, A. Mental Health challenges in Cancer patients: A cross-sectional analysis of depression and anxiety. Cancers 2024, 16, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, J.A.M.; Spieß, E.; Pfaffinger, K.F. Perception and Appraisal of Stressors. In Dealing with Stress in a Modern Work Environment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelier, D.M.; Jackson, C.; Bridel, W.; Grant, C.; Culos-Reed, S.N. Coping strategies in active and inactive men with prostate cancer: A qualitative study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Farahani, M.A.; Khachian, A.; Vaismoradi, M. Fear of cancer recurrence and coping strategies among prostate cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 6720–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.; Haase, K.R.; Bradley, C.; Papadopoulos, E.; Kuster, S.; Santa Mina, D.; Tippe, M.; Kaur, A.; Campbell, D.; Joshua, A.M.; et al. Barriers and facilitators related to undertaking physical activities among men with prostate cancer: A scoping review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 1007–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Goodwin, B.C.; Myers, L.; Stiller, A.; Dunn, J.; Aitken, J.F.; March, S. Survivorship care plans and information for rural cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E. Male sexual dysfunction and rehabilitation strategies in the settings of salvage prostate cancer treatment. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2021, 33, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, A.M.; Ojala, H.; Tammela, T.; Pietilä, I. Prostate cancer-related sexual dysfunction–the significance of social relations in men’s reconstructions of masculinity. Cult. Health Sex. 2024, 26, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Song, M.K. State of the science of sexual health among older cancer survivors: An integrative review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipiti, T.; Molefi, T.; Demetriou, D.; Lolas, G.; Dlamini, Z. Survivorship and Quality of Life: Addressing the Physical and Emotional Well-Being of Prostate Cancer Patients. In Transforming Prostate Cancer Care: Advancing Cancer Treatment with Insights from Africa; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, A.D.; Gentle, C.K.; Ortega, C.; Al-Hilli, Z. Disparities in breast Cancer Care—How factors related to Prevention, diagnosis, and Treatment Drive Inequity. Healthcare 2024, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Shan, H.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Shen, Y.; Shi, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on family functioning and psychological resilience in prostate cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1392167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, L.E.; Clement, C.; Ochieng, C.A.; Lewis, A.L.; Chapple, C.; Abrams, P.; Drake, M.J.; Horwood, J. Treatment decision-making among men with lower urinary tract symptoms: A qualitative study of men’s experiences with recommendations for patient-centred practice. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2021, 40, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, J.; Schartau, P.; Murray, E. Supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer: A systematic review update. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI, 2022). Cancer in Ireland 1994–2022: Annual Statistical Report 2022. Available online: https://www.ncri.ie/sites/ncri/files/pubs/NCRI_AnnualStatisticalReport_2022.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Hsieh, A.R.; Luo, Y.L.; Bao, B.Y.; Chou, T.C. Comparative analysis of genetic risk scores for predicting biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldred-Evans, D.; Connor, M.J.; Bertoncelli Tanaka, M.; Bass, E.; Reddy, D.; Walters, U.; Stroman, L.; Espinosa, E.; Das, R.; Khosla, N.; et al. The rapid assessment for prostate imaging and diagnosis (RAPID) prostate cancer diagnostic pathway. BJU Int. 2023, 131, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polascik, T.J.; Passoni, N.M.; Villers, A.; Choyke, P.L. Modernizing the diagnostic and decision-making pathway for prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6254–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service. Faster Diagnostic Pathways Implementing a Timed Prostate Cancer Diagnostic Pathway Guidance for Local Health and Care Systems; National Health Service: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/B1348_Prostate-cancer-timed-diagnostic-pathway.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Bradshaw, C.; Atkinson, S.; Doody, O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2017, 4, 2333393617742282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, E.Y.; Jang, S.G.; Ock, M. Qualitative research in healthcare: Necessity and characteristics. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 56, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Description | Application to Study |

|---|---|---|

| Phase One: data familiarization | This stage is reading and rereading transcript to dote down initial impression | Researchers went through all 11 interviews and noted down the need information e.g., Emotional needs, unmet needs. |

| Phase Two: Code generation | At this stage, one systematically looks for meaningful features or patterns across all data inductively and reflectively. | Researchers generated codes like shock, fear, anxiety with the help of a qualitative analysis software. |

| Phase Three: Searching of theme | Codes are grouped together to make meaningful sub-themes or themes. | Generated codes were used by researchers to form subthemes like psychological adaptation and coping mechanisms. |

| Phase Four: Reviewing of themes generated | Generated themes reviewed in relation coded data ensuring correlation, cohesion and accuracy. | Sub-themes reviewed again in relation to the codes to help ensure correlation and distinctions. |

| Phase Five: Naming and Defining themes | Finally theme clearly defined, named and described. | Researchers ensure identified theme final theme is distinct and has never been used or identified in other literatures. |

| Phase Six: Report production | Writing a narrative about the generated themes with supporting evidence. | Developed themes were used by the researchers to write a cohesive narration to make a meaningful statement. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mumuni, S.; O’Donnell, C.; Doody, O. Lived Experience of Men with Prostate Cancer in Ireland: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091049

Mumuni S, O’Donnell C, Doody O. Lived Experience of Men with Prostate Cancer in Ireland: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091049

Chicago/Turabian StyleMumuni, Seidu, Claire O’Donnell, and Owen Doody. 2025. "Lived Experience of Men with Prostate Cancer in Ireland: A Qualitative Descriptive Study" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091049

APA StyleMumuni, S., O’Donnell, C., & Doody, O. (2025). Lived Experience of Men with Prostate Cancer in Ireland: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Healthcare, 13(9), 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091049