Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor and Related Dysfunctions: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

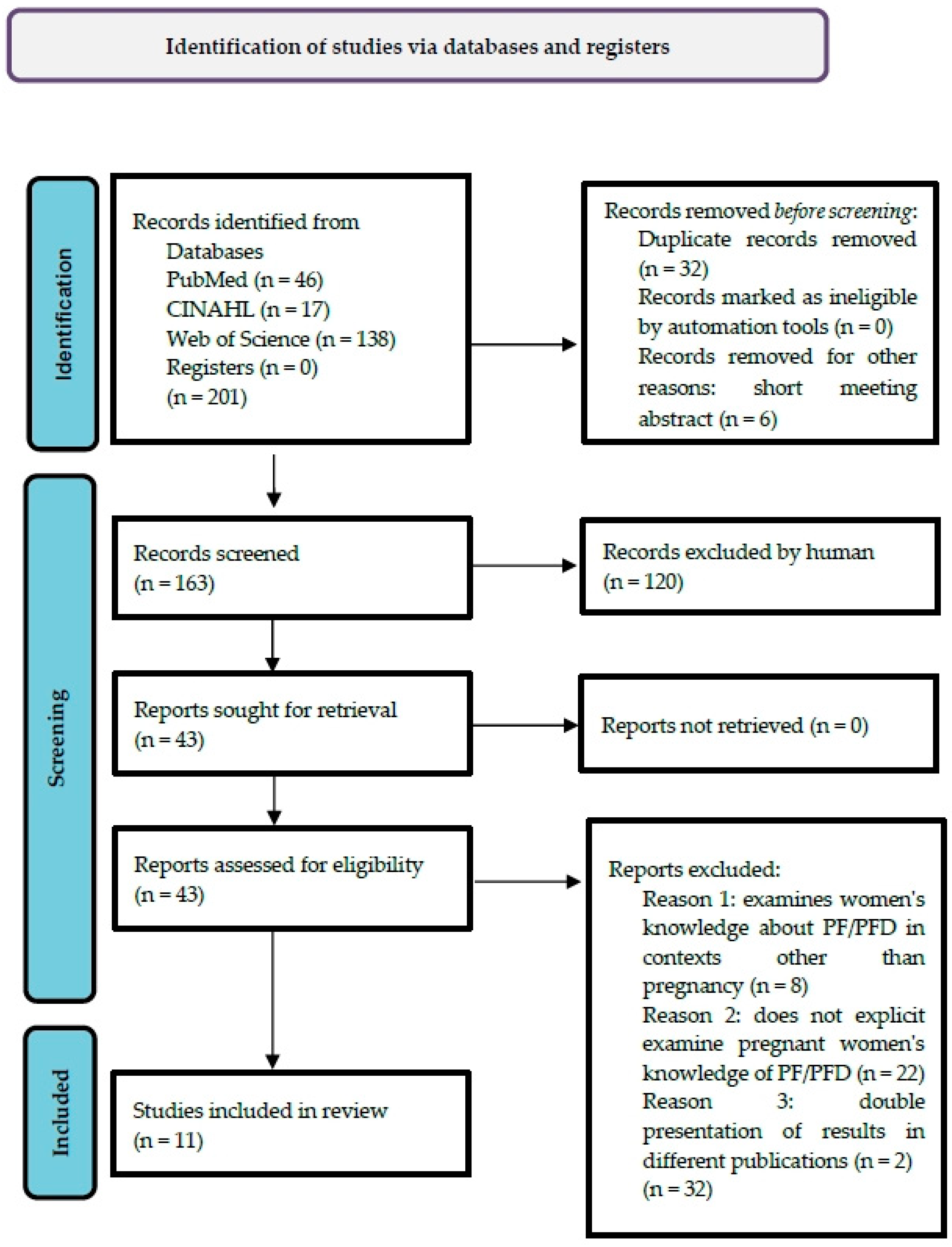

2. Methods

- What ideas do pregnant women have about PF anatomy and PFF?

- What basic knowledge is available on PFD in the context of pregnancy and birth?

- What is the level of knowledge on the prevention of PFD or on measures to restore PF health in the case of pregnancy-associated PFD?

- What factors promote an improvement in the level of knowledge of pregnant women regarding the PF and possible pregnancy-associated PFDs?

- Which medical services are sought by pregnant women with PFDs?

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Sources of Evidence

3.2. Literature Synthesis

3.2.1. Knowledge and Ideas About Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Pelvic Floor Functions

3.2.2. Basic Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Dysfunctions (UI, POP, FI) in the Context of Pregnancy and Birth

3.2.3. State of Knowledge on the Prevention of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction or on Measures to Restore Pelvic Floor Health in the Presence of Pregnancy-Associated Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

3.2.4. Factors That Support an Improvement in Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of the Pelvic Floor and Possible Pregnancy-Associated Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

3.2.5. Seeking Medical Help for Pregnant Women in the Event of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results

4.1.1. Knowledge and Ideas About Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Pelvic Floor Functions

4.1.2. Basic Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Dysfunctions (UI, POP, FI) in the Context of Pregnancy and Birth

4.1.3. State of Knowledge on the Prevention of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction or on Measures to Restore Pelvic Floor Health in the Presence of Pregnancy-Associated Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

4.1.4. Factors That Support an Improvement in Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of the Pelvic Floor and Possible Pregnancy-Associated Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

4.1.5. Seeking Medical Help for Pregnant Women in the Event of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Research Gaps and Future Directions

4.4. Implications for Midwifery Science and Broader Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blomquist, J.L.; Munoz, A.; Carroll, M.; Handa, V.L. Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth. JAMA 2018, 320, 2438–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Geelen, H.; Ostergard, D.; Sand, P. A review of the impact of pregnancy and childbirth on pelvic floor function as assessed by objective measurement techniques. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerruto, M.A.; D’Elia, C.; Aloisi, A.; Fabrello, M.; Artibani, W. Prevalence, incidence and obstetric factors’ impact on female urinary incontinence in Europe: A systematic review. Urol. Int. 2013, 90, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M.; Junginger, B.; Henrich, W.; Baessler, K. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire for the Assessment of Pelvic Floor Disorders and Their Risk Factors During Pregnancy and Post Partum. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017, 77, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyhagen, M.; Bullarbo, M.; Nielsen, T.F.; Milsom, I. The prevalence of urinary incontinence 20 years after childbirth: A national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. BJOG 2013, 120, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, C.; Wilson, D.; Herbison, P.; Lancashire, R.J.; Hagen, S.; Toozs-Hobson, P.; Dean, N.; Glazener, C.; Prolong study, g. Urinary incontinence persisting after childbirth: Extent, delivery history, and effects in a 12-year longitudinal cohort study. BJOG 2016, 123, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundt, K.; Peschers, U.; Kentenich, H. The investigation and treatment of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, M.B.R.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L.M. Women’s perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: A qualitative interview study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moossdorff-Steinhauser, H.F.A.; Berghmans, B.C.M.; Spaanderman, M.E.A.; Bols, E.M.J. Prevalence, incidence and bothersomeness of urinary incontinence in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 1633–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkved, S.; Bo, K. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy and after childbirth on prevention and treatment of urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodley, S.J.; Lawrenson, P.; Boyle, R.; Cody, J.D.; Morkved, S.; Kernohan, A.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD007471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafne, S.N.; Salvesen, K.Å.; Romundstad, P.R.; Torjusen, I.H.; Morkved, S. Does regular exercise including pelvic floor muscle training prevent urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. Bjog-Int. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2012, 119, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, M.; Eshraghi, N.; Naeiji, Z.; Fathi, M. Evaluation of Awareness, Adherence, and Barriers of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in Pregnant Women: A Cross-sectional Study. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 27, e122–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfers, R. Gesundheitsförderung Durch Hebammen. Fürsorge und Prävention Rund um Mutterschaft und Geburt; Schattauer-Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gesetz Über das Studium und den Beruf von Hebammen (HebG). Hebammengesetz vom 22. November 2019 (BGBl. I S. 1759), das Durch Artikel 10 des Gesetzes vom 24. Februar 2021 (BGBl. I S. 274) Geändert Worden ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/hebg_2020/BJNR175910019.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- von Elm, E.; Schreiber, G.; Haupt, C.C. Methodische Anleitung für Scoping Reviews (JBI-Methodologie). Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes 2019, 143, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-checklist (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts: Reporting Systematic Reviews in Journal and Conference Abstracts. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/prisma-abstracts/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- PRISMA Flow Diagram. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- McKay, E.R.; Lundsberg, L.S.; Miller, D.T.; Draper, A.; Chao, J.; Yeh, J.; Rangi, S.; Torres, P.; Stoltzman, M.; Guess, M.K. Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders in Obstetrics. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 25, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.T.; Hockey, J.; O’Brien, P.; Williams, A.; Morris, T.P.; Khan, T.; Hardwick, E.; Yoong, W. Knowledge of pelvic floor problems: A study of third trimester, primiparous women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farihan, M.N.; Ng, B.K.; Phon, S.E.; Azlin, M.I.N.; Azurah, A.G.N.; Lim, P.S. Prevalence, Knowledge and Awareness of Pelvic Floor Disorder among Pregnant Women in a Tertiary Centre, Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geynisman-Tan, J.M.; Taubel, D.; Asfaw, T.S. Is Something Missing From Antenatal Education? A Survey of Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 24, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.M.; McPhail, S.M.; Wilson, J.M.; Berlach, R.G. Pregnant women’s awareness, knowledge and beliefs about pelvic floor muscles: A cross-sectional survey. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, S.Q.; Han, H.C. Knowledge of pelvic floor disorder in pregnancy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlas, M.; Bilgic, D. Awareness of urinary incontinence in pregnant women as a neglected issue: A cross-sectional study. Malawi Med. J. 2024, 36, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennfjord, M.K.; Kassie, B.A.; Gashaw, Z.M.; Asaye, M.M.; Muche, H.A.; Fenta, T.T.; Chala, K.N.; Maeland, K.S. Pelvic Floor Disorders and Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise: A Survey on Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice among Pregnant Women in Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak Celenay, S.; Coban, O.; Korkut, Z.; Alkan, A. Do community-dwelling pregnant women know about pelvic floor disorder? Women Health 2021, 61, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohay, N.Z.; Weiss, A.; Weintraub, A.Y.; Daya, K.; Katz, M.E.; Elharar, D.; Yohay, Z.; Madar, R.T.; Eshkoli, T. Knowledge of women during the third trimester of pregnancy regarding pelvic floor disorders. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 3407–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammers, I.; Sperandio, F.; Sacomori, C.; Moreira, G.; Cardoso, F. Knowledge and perceptions of pregnant women about the reproductive system: A qualitative study. Man. Ther. Posturol. Rehabil. J. 2021, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.D.; Massagli, M.P.; Kohli, N.; Rajan, S.S.; Braaten, K.P.; Hoyte, L. A reliable, valid instrument to assess patient knowledge about urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor. Dysfunct. 2008, 19, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.D.; Walters, M.D.; Bump, R.C. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Williams, B.A. Knowledge of urinary incontinence among Chinese community nurses and community-dwelling older people. Health Soc. Care Community 2010, 18, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvey, L.; Salameh, F.; O’Sullivan, O.E.; O’Reilly, B.A. What Does Your Pelvic Floor Do for You? Knowledge of the Pelvic Floor in Female University Students: A Cross-sectional Study. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 27, e457–e464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neels, H.; Wyndaele, J.J.; Tjalma, W.A.; De Wachter, S.; Wyndaele, M.; Vermandel, A. Knowledge of the pelvic floor in nulliparous women. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas, L.M.; Bo, K.; Fernandes, A.; Uechi, N.; Duarte, T.B.; Ferreira, C.H.J. Pelvic floor muscle knowledge and relationship with muscle strength in Brazilian women: A cross-sectional study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiruga, M.B.; Delgado-Morell, A.; Garcia, M.P.; Girona, S.C.; Saladich, I.G.; Roda, O.P. What do female university students know about pelvic floor disorders? A cross-sectional survey. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F.; Hadi, H.; Ismail, I.; Osborne, R.H.; Ekstrom, C.T.; Kayser, L. ehealth literacy and health literacy among immigrants and their descendants compared with women of Danish origin: A cross-sectional study using a multidimensional approach among pregnant women. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato, A.C.; Deparis, J.; Fritel, X.; Rousseau, M.; Blanchard, V. Impact of educational workshops to increase awareness of pelvic floor dysfunction and integrate preventive lifestyle habits. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2024, 164, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLancey, J.O.L.; Masteling, M.; Pipitone, F.; LaCross, J.; Mastrovito, S.; Ashton-Miller, J.A. Pelvic floor injury during vaginal birth is life-altering and preventable: What can we do about it? Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2024, 230, 279–294.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; Meschede, J.; Reister, F.; Deniz, M. Aufklärung über Schwangerschafts- und geburtsbedingte Veränderungen des weiblichen Beckenbodens aus urogynäkologischer Sicht. Gynäkologie 2023, 56, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliktas, A.; Kukulu, K. Pregnant Women in Turkey Experience Severe Fear of Childbirth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Are Midwifes Do. Available online: https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/the-role-of-your-midwife (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Antenatal Classes. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/labour-and-birth/preparing-for-the-birth/antenatal-classes/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Demirci, A.D.; Kabukcuglu, K.; Haugan, G.; Aune, I. “I want a birth without interventions”: Women’s childbirth experiences from Turkey. Women Birth 2019, 32, E515–E522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricchi, A.; La Corte, S.; Molinazzi, M.T.; Messina, M.P.; Banchelli, F.; Neri, I. Study of childbirth education classes and evaluation of their effectiveness. Clin. Ter. 2020, 171, E78–E86. [Google Scholar]

- Avignon, V.; Gaucher, L.; Baud, D.; Legardeur, H.; Dupont, C.; Horsch, A. What do mothers think about their antenatal classes? A mixed-method study in Switzerland. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2023, 23, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, Y.C.; O’Connell, B.; Phillips, D. Peripartum urinary incontinence: A study of midwives’ knowledge and practices. Women Birth 2007, 20, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, R.; Jarvie, R.; Hay-Smith, J.; Salmon, V.; Pearson, M.; Boddy, K.; MacArthur, C.; Dean, S. “Are you doing your pelvic floor?” An ethnographic exploration of the interaction between women and midwives about pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFME) during pregnancy. Midwifery 2020, 83, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, C.; Wilson, D.; Herbison, P.; Lancashire, R.J.; Hagen, S.; Toozs-Hobson, P.; Dean, N.; Glazener, C.; ProLong study group. Faecal incontinence persisting after childbirth: A 12 year longitudinal study. BJOG 2013, 120, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M.R.; Patricia, L.W.; Loughran, S.; O’Sullivan, E. Community-dwelling women’s knowledge of urinary incontinence. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2014, 19, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.M.B.; Lima, C.; Ferreira, C.W.S. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in high-impact sports athletes and their association with knowledge, attitude and practice about this dysfunction. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2018, 18, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerle, G.; Mattern, E. Priority topics for research by midwives: An analysis of focus groups with pregnant women, mothers and midwives. GMS Z. Für Hebammenwissenschaft 2017, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nawabi, F.; Krebs, F.; Vennedey, V.; Shukri, A.; Lorenz, L.; Stock, S. Health Literacy in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willburger, B.; Chen, Z.; Mansfield, K.J. Investigation of the quality and health literacy demand of online information on pelvic floor exercises to reduce stress urinary incontinence. Aust. N. Z. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2024, 64, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, K.; Sherburn, M. Evaluation of female pelvic-floor muscle function and strength. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laycock, J.; Jerwood, D. Pelvic Floor Muscle Assessment: The PERFECT Scheme. Physiotherapy 2001, 87, 631–641. [Google Scholar]

- NICE Guideline [NG210]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng210 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Okeahialam, N.A.; Oldfield, M.; Stewart, E.; Bonfield, C.; Carboni, C. Pelvic floor muscle training: A practical guide. Bmj 2022, 378, e070186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.P.; Day, L.T.; Rezende-Gomes, A.C.; Zhang, J.; Mori, R.; Baguiya, A.; Jayaratne, K.; Osoti, A.; Vogel, J.P.; Campbell, O.; et al. A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e306–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berufspolitik. Available online: https://hebammenverband.de/berufspolitik#positionen (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Yelland, J.; Riggs, E.; Small, R.; Brown, S. Maternity services are not meeting the needs of immigrant women of non-English speaking background: Results of two consecutive Australian population based studies. Midwifery 2015, 31, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befristete Übergangsvereinbarung zur Anpassung der Vergütung für Leistungen der Hebammenhilfe nach § 134a Abs. 1 SGB V vom 7 February 2024. Available online: https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/ambulante_leistungen/hebammen/aktuelle_dokumente/24-02-07_Uebergangsvereinbarung_Verguetungsanpassung_Hebammen.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- AWMF-Registernummer 015-091-Harninkontinenz der Frau. Available online: https://www.awmf.org/service/awmf-aktuell/harninkontinenz-der-frau. (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- The State of the World’s Children. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/165156/file/SOWC-2024-full-report-EN.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Uzan, L.M.; Brust, M.; Molenaar, J.M.; Leistra, E.; Boor, K.; Jong, J.C.K.D. A cross-sectional analysis of factors associated with the teachable moment concept and health behaviors during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockliffe, L.; Peters, S.; Heazell, A.E.P.; Smith, D.M. Understanding pregnancy as a teachable moment for behaviour change: A comparison of the COM-B and teachable moments models. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2022, 10, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P | Population | pregnant women |

| C | Concept | knowledge |

| C | Context | pelvic floor and pelvic floor disorders |

| PubMed Search Strings: Listed According to PCC | Results | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 P | “pregnanc*” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pregnant Women” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pregnant Woman” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pregnancy” [MeSH Terms] OR “Pregnant Women” [MeSH Terms] | 1,158,974 | 29 July 2024 |

| #2 C | “level of awareness” [Title/Abstract] OR “knowledge pregnant women” [Title/Abstract:~2] OR “Health Literacy” [MeSH Terms] OR “health knowledge, attitudes, practice” [MeSH Terms] | 140,771 | 29 July 2024 |

| #3 C | “Pelvic Floor” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pelvic Floor” [MeSH Terms] OR “Pelvic Floor Disorders” [MeSH Terms] | 14,824 | 29 July 2024 |

| #4 total-term | (“Pelvic Floor” [Title/Abstract] OR (“Pelvic Floor” [MeSH Terms] OR “Pelvic Floor Disorders” [MeSH Terms])) AND (“pregnanc*” [Title/Abstract] OR (“Pregnant Women” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pregnant Woman” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“Pregnancy” [MeSH Terms] OR “Pregnant Women” [MeSH Terms])) AND (“level of awareness” [Title/Abstract] OR “knowledge pregnant women” [Title/Abstract:~2] OR (“Health Literacy” [MeSH Terms] OR “health knowledge, attitudes, practice” [MeSH Terms])) | 46 | 29 July 2024 |

| CINAHL Search Strings: listed according to PCC | Results | Date | |

| #1 P | (MH “Pregnancy+”) OR (MH “Expectant Mothers”) OR TX (pregnancy* OR “pregnant women”) | 300,841 | 31 July 2024 |

| #2 C | (MH “Health Literacy”) OR (MH “Health Knowledge”) OR TX (“health literacy” OR (health N2 knowledge) OR (level N2 awareness)) | 62,505 | 31 July 2024 |

| #3 C | (MH “Pelvic Floor Muscles”) OR (MH “Pelvic Floor Disorders”) OR TX “pelvic floor” | 6208 | 31 July 2024 |

| #4 total-term | ((MH “Pregnancy+”) OR (MH “Expectant Mothers”) OR TX (pregnanc* OR “pregnant women”)) AND ((MH “Health Literacy”) OR (MH “Health Knowledge”) OR TX (“health literacy” OR (health N2 knowledge) OR (level N2 awareness))) AND ((MH “Pelvic Floor Muscles”) OR (MH “Pelvic Floor Disorders”) OR TX “pelvic floor”) | 17 | 31 Juli 2024 |

| Web of Science Core Collection Search String: listed according to PCC | Results | Date | |

| #1 P | TS = (pregnanc* OR “pregnant women” OR “pregnant woman”) | 610,786 | 05 August 2024 |

| #2 C | TS = ((Health NEAR/2 (Knowledge OR literacy)) OR Awareness) | 2,409,636 | 05 August 2024 |

| #3 C | TS = (“pelvic floor*”) | 16,216 | 05 August 2024 |

| #4 total-term | ((TS = (pregnancy* OR “pregnant women” OR “pregnant woman”)) AND TS = (Knowledge OR “health literacy” OR Awareness)) AND TS = (“pelvic floor*”) | 138 | 05 August 2024 |

| Articles addressing the aspects of PCC (pregnant women, knowledge, pelvic floor, and pelvic floor disorders) |

| Articles in English and German languages |

| Articles published January 2004 onwards to 31. July 2024 |

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Country | Objektive | Population/Sample Size | Setting | Methodology | Screening Tool(s) and Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mckay et al. [23] | 2019 | Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders in Obstetrics | USA | This study aimed to investigate the knowledge and demographic factors associated with a lack of knowledge about UI (POP) in pregnant and postpartum women. | Pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy or women within 8 weeks postpartum n = 399 nulliparity: 33.2% primiparity: 33.2% multiparity (>2): 32.4% postpartum women: 6.8% mean age 28.5 ± 6.0 years | Women were recruited at 9 locations, including outpatient clinics, private practices, and hospital-based antenatal, labour and delivery units. Each of them was tied together with three major hospitals: Yale New Haven Hospital, Yale New Haven Bridgeport Hospital, and Danbury Hospital/ Western Connecticut Health Network. | A multicentre, cross-sectional survey statistical tests: descriptive presentation in mean and standard deviation and/or percentages using logistic regression; multivariate logistic regression | PIKQ; additional PFDI-20 |

| O’Neill et al. [24] | 2016 | Knowledge of pelvic floor problems: a study of third trimester, primiparous women | UK | This study aims to explore the knowledge of PFD in pregnant primiparous women in the 3rd trimester. | Primiparous pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy; n = 249 Mean gestational age: 33 ± 5 weeks mean age 30 ± 6 years; | The study took place in 3 maternity hospitals in London, UK. | A multicentre, cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests: mean and standard deviation; multivariable linear regression | Using a self-designed, validated questionnaire (based on PIKQ) |

| Farihan et al. [25] | 2022 | Prevalence, Knowledge, and Awareness of Pelvic Floor Disorder among Pregnant Women in a Tertiary Centre, Malaysia. | Malaysia | This study aimed to assess the knowledge and awareness about the PF and PFD among pregnant women in a tertiary Centre in Malaysia. In addition, the relationship between women’s risk factors regarding their knowledge and awareness of the PF should be evaluated. | Nulliparous and multiparous pregnant women; gestational age > 18 weeks n = 424 primiparity: 33.3% multiparity: 66.7%; median of gestational age: 36.1 (32.0, 38.2) weeks; median age: 31.5 (29.0, 35.0) years | The study took place in a maternity centre in Malaysia. All included pregnant women were interviewed on site using questionnaires. | Cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests: Chi2 test; mean and standard deviation/median and interquartile range | PIKQ; additional PFDI-20 |

| Geynisman-Tan et al. [26] | 2017 | Is Something Missing From Antenatal Education: A Survey of Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders. | USA | This study aimed to describe the knowledge of PFD among a cross-section of pregnant women. | Nulliparous and multiparous pregnant women; gestational age > 18 weeks; n = 402 primiparity: not listed multiparity: not listed mean age ± SD: 34 ± 6 years | The study was carried out in New York Presbyterian Prenatal Department Hospital. During their waiting period, the women included were interviewed by research assistants using a questionnaire. | Cross-sectional survey study statistical tests: Kruskal–Wallis test; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; paired knowledge questions were analysed by McNemar test. | PIKQ |

| Hill et al. [27] | 2017 | Pregnant women’s awareness, knowledge, and beliefs about pelvic floor muscles: a cross-sectional survey, | Australia | The aims of the study were to evaluate pregnant women’s levels of awareness, knowledge, and beliefs about the PFMs and PFMEs. | Nulliparous and multiparous pregnant women; n = 633 primiparity: 50.1% multiparity: 48.2% mean gestational age: 28.7 ± 7.8 weeks mean age: 29.2 ± 5.3 years | The study was conducted in various health facilities of the Department of Health, Western Australia (DoHWA). Included women were able to complete the survey on site and online. | Cross-sectional survey study statistical tests: Cross-tabulations of Chi2 tests; Fisher’s exact tests | Using a self-designed, validated, and piloted questionnaire with outcome measures awareness of PFMs and knowledge of PFMs and PFMEs, and the role of PFMs as a key function in preventing UI |

| Liu et al. [28] | 2019 | Knowledge of pelvic floor disorder in pregnancy. | Singapore | The aims of this study were to assess the level of knowledge about pelvic floor disorders among pregnant women in a local population. | Nulliparous and multiparous pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy; n = 104 nulliparity: 50.0% multiparity: 50.0% mean gestational age: 34.4 ± 3.8 (28–41) mean age 30.6 ± 5.0 years; | The study was conducted at the KKWomen’s and Children’s Hospital maternity clinics using self-administered questionnaires. | Cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests: one-way ANOVA analysis; nonparametric tests | Using a self-designed, validated 47-item questionnaire with outcome measures, knowledge of PFD (UI/POP/FI), and how they relate to pregnancy and childbirth |

| Parlas and Bilgic [29] | 2024 | Awareness of urinary incontinence in pregnant women as a neglected issue: a cross-sectional study | Turkey | The aim of this study is to determine the UI awareness of pregnant women and their knowledge and attitudes in this context. | Pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy n = 255 nulliparity: 42% primiparity: 38% multiparity: 20% gestational age of included women: first trimester: 7.5% second trimester: 32.9% third trimester: 59.6% mean age 29.2 ± 5.1 years | Face-to-face interview in a university hospital in Turkey. | A cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests: descriptive statistical methods; Independent samples t-test, one-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation test | PIKQ: whereby only the survey on UI was carried out; Additionally, UIAS |

| Tennfjord et al. [30] | 2023 | Pelvic Floor Disorders and Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise: A Survey on Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice among Pregnant Women in Northwest Ethiopia | Ethiopia | The aim of the study was to examine POP and UI as well as the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of PFME. Furthermore, the connection of these factors with parity in pregnant women in Gondar, Ethiopia. | Pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy; n = 502 nulliparity: 26.5% multiparity: 73.5% mean age 28.1 + 6.2 years | Data collection was carried out in 7 randomly selected antenatal care health centres in the central Gondar zone (Gondar City; Wogera; Dembia Gondar Zuria) using face-to-face interviews. | A facility-based cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests: regression models | PIKQ; additional questions about knowledge, attitude, and practice to PFME |

| Toprak Celenay et al. [31] | 2021 | Do community-dwelling pregnant women know about pelvic floor disorder? | Turkey | The study aimed to assess knowledge and awareness about pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) in pregnant women. Whether knowledge about PFDs depends on gestational age, parity, participation in an ANE or history of UI and/or POP was also examined | Pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy n = 241 nulliparity: 78.2% multiparity: 21.8% median gestational age: 21 (4–40) weeks mean age 29.03 + 4.66 years; | Face-to-face setting at two gynaecology and obstetrics clinics, including a private clinic and a training and research hospital, | A cross-sectional descriptive study with survey statistical tests: mean and standard deviation; median; Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test; KR-20 coefficient | PIKQ; Three additional targeted questions were used to assess pregnant women’s awareness of UI and POP |

| Yohay et al. [32] | 2022 | Knowledge of women during the third trimester of pregnancy regarding pelvic floor disorders | Israel | The aim of this study was to objectively assess the knowledge regarding pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) among women during the third trimester of pregnancy. | Pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy. n = 649 nulliparity: 26.3% multiparity: 73.7% Hebrew: 405 Arabic: 244; median gestational age: not listed weeks mean age 30.48 ± 5.91 years | Large university medical centre in Israel | A cross-sectional study with survey statistical tests:using mean and standard deviation, t-test or one-way ANOVA; calculation of the Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient. | PIKQ |

| Kammers et al. [33] | 2021 | Knowledge and perceptions of pregnant women about the reproductive system | Brazil | To understand the perception of some adult Brazilian pregnant women in relation to the importance attributed to the biological body from the perspective of the reproductive system and the PF during pregnancy. | Nulliparous, primiparous, and multiparous pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy; n = 13 mean age: not listed | The study took place at the time of the antenatal visit in the waiting room of the health centres of the city of Florianópolis/Santa Catarina. Interviews and graphic preparations were carried out in a private room adjacent to the waiting room. | Qualitative study with semi-structured interviews | Using a semi-structured interview guide and a graphical representation of the reproductive system and pelvic floor, and complementary sociodemographic data |

| Author(s) | Important Results | Derived Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Mckay et al. [23] | Results showed low knowledge regarding UI and POP in included women. A total of 74.2% of included women showed a lack of knowledge proficiency about UI, and 70.6% showed a lack of POP knowledge proficiency. Overall, 49.7% of included women knew that childbirth was a risk factor for UI, and 29.2% knew that childbirth was a risk factor for POP. Among symptomatic women who reported UI, approximately 41% did not know that childbirth was a risk factor for their symptoms. After adjustment, Hispanic women, primiparous women, and women with lower levels of education were significantly more likely to lack knowledge proficiency regarding UI. The final model for POP knowledge showed that women with a high school diploma or less were more likely to lack POP knowledge compared to women with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Women who had previous visits to a urologist or urogynecologist were less likely to lack POP knowledge. Pregnant women working in a medical field were less likely to lack UI and POP knowledge compared to those who did not (ORs: 0.26 [95% CI: 0, 13–0.52] and 0.38 [95% CI: 0.21–0.70]). Pelvic floor disorder during pregnancy was common; 39% of pregnant women acknowledged having UI; 4.8% experienced symptoms of POP. | The results of the study show that an effective educational strategy for risk reduction and the inclusion of women from socio-economic backgrounds with higher risk is necessary to expand knowledge about PFM and PFD. Standardized educational sessions by healthcare professionals to discuss issues related to PFDs and their treatment options during pregnancy are recommended. The focus should be on the range of interventions, including behavior modification, pelvic floor exercises, and use of pessaries, to improve women’s quality of life. |

| O’Neill et al. 2016 [24] | Results showed low knowledge regarding UI, POP, and FI in the included pregnant women. The average knowledge score across all areas was low at 45%. The average composite knowledge score was the highest in the domains of UI (63%), but low when questions covered more detailed knowledge levels (41%, further POP (36%), and the lowest knowledge score in the domain of FI (35%). There is a positive association between knowledge scores and education to a tertiary level, where knowledge scores were 18% lower in women educated to mid-secondary school level than in those educated to tertiary/degree level. The most commonly cited information sources on pregnancy and delivery used by the respondents were the internet (84%), books (82%), further sources were also the midwife (72%), doctor (65%), and ANE, only 35%. | An important source of knowledge is healthcare professionals (doctors and midwives). They should take their task more seriously to address pelvic floor problems early in pregnancy and provide information about them to make it easier for women to access information. There is also potential for improvement in the content conveyed in the ANE. The lack of a positive relationship between the level of knowledge and the use of the most popular source of information—the internet—points out that there is room for improvement in online content. |

| Farihan et al. 2022 [25] | Results showed low knowledge regarding UI and POP in the included pregnant women. A total of 80.4% of included pregnant women had a low level of knowledge regarding UI, and 45.0% had a low level of knowledge about POP. The median total score for knowledge about pelvic floor disorders was 12 points, which was considered low (cut-off point of 16). The median knowledge score PIKQ UI was 7 points, and the median knowledge score PIKQ POP was 6 points. Having a tertiary level of education and receiving antenatal specialist care were associated with better knowledge regarding PF, UI, and POP (p = 0.000). Pelvic floor disorder during pregnancy was common; 46.1% of included pregnant women had at least one symptom of PFD during pregnancy, 62.7% experienced symptoms of UI, 41.8% experienced symptoms of POP, and 37.8% experienced symptoms of FI. | In principle, increasing levels of education and prenatal specialist medical care are associated with better knowledge of the pelvic floor and possible dysfunctions. A fundamental new educational program to bridge knowledge gaps about PFD in pregnant women and women is necessary. |

| Geynisman-Tan et al. 2017 [26] | Results showed poor knowledge regarding UI and POP in the included pregnant women. The mean ± SD knowledge score for PIKQ UI was 7.9 points (66 ± 12% correct answers). The mean ± SD knowledge score for PIKQ POP was 4.9 points (41 ± 17% correct answers). Pregnant women were more likely to know that delivery could result in incontinence (62%) than pelvic organ prolapse (42%; p = 0.02). At least 83% of pregnant women knew that pelvic floor exercises can prevent urinary incontinence. There is a lack of knowledge about exercises to prevent POP. Only 55% of study participants correctly answered: “Certain exercises can help prevent POP from getting worse”; p < 0.001. | Although pregnant women often have pelvic floor problems with a high risk of pelvic floor dysfunction and therefore increasingly consult doctors, they still do not have adequate knowledge about pelvic floor dysfunction. Prenatal care, education, and patient empowerment must be improved here. Future studies focused on providing information about improving pelvic floor health are needed for women and pregnant women about PFDs and their possible treatment focus during pregnancy and after birth. |

| Hill et al. 2017 [27] | The findings show a very limited knowledge in the included pregnant women about the anatomy and function of the PFMs, further UI, and PFMEs. Although 76% of included women knew that PFMs can prevent UI, 27% of them knew that they prevented FI. A total of 41% of included pregnant women thought it was normal to leak urine when pregnant. Only 5.4% of included pregnant women were able to correctly assess the anatomy of the PF, and 20.7% could not identify any PFM function. Only 11% of the included pregnant women practiced PFMEs. Study participants who had ANE (28%) were significantly more knowledgeable about pelvic floor function (p < 0.001). Included pregnant women who did not speak English at home (18%) were significantly less knowledgeable about PFMs and PFMEs (p < 0.001), and significantly less likely to have attended, or planned to attend, ANE classes (p < 0.001). The main source of knowledge for the included pregnant women to acquire knowledge about PFM and PFMEs is the internet. | A deeper educational approach and further research appear necessary to further expand the awareness and knowledge of PFMs among pregnant women at all levels of education. ANE is an important basis for promoting pelvic floor health. Pregnant women need more health education regarding PFMs. Education should be diverse, especially for women with a migrant background. Further research is needed to effectively expand comprehensive methods of providing ANE to pregnant women to increase their knowledge and awareness of PFMs. They should be supported in developing their skills and motivation to engage in PFMEs. |

| Liu et al. 2019 [28] | Results showed low knowledge regarding UI and POP in the included pregnant women. The knowledge score for UI was the highest (mean score of 46.2% ± 0.3). The knowledge score for FI was 39.8% ± 0.3 and for POP was 35.3% ± 0.3. Mean knowledge scores increased significantly with educational level (p = 0.046) and age (p = 0.021). There is a lack of knowledge about and prevention of UI; 40% of included women do not know that PFMEs in pregnancy can help to prevent UI after childbirth. Pelvic floor disorder during pregnancy was common; 31.7% of included women reported experiencing urinary incontinence, 2.9% of respondents reported POP, and 0.96% had FI. None of the women sought medical attention or treatment for these conditions. | The level of knowledge about the pelvic floor and possible dysfunctions highlights the importance of educating young women of reproductive age about protecting their pelvic floor health. It is important to reevaluate public education campaigns on prenatal care to empower women of childbearing age to make more informed decisions about performing pelvic floor exercises to reduce the risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction. |

| Parlas and Bilgic 2024 [29] | Results showed low knowledge about UI among pregnant women. Only 6.3% of the participants correctly answered all of the items in the UI knowledge scale; the mean score of PIKQ UI was 8.07 ± 2.64. A total of 44% did not know what to do to prevent and manage UI. More than half of the pregnant women (62.8%) had not heard about PFME, and most of them (83.5%) did not perform PFME. The mean UIAS score was 42.33 ± 3.48. The results showed a positive correlation between UI knowledge and attitude value (r = 0.35, p = 0.00). Pelvic floor disorder during pregnancy was common. The prevalence of UI was 51% during pregnancy. | There is an urgent need for education about UI and women’s attitudes towards UI. Pregnant women should be educated about UI and its symptoms and how to manage it. They should be encouraged to visit health services, nurses, and midwives for early counselling on UI. Specific health education and counselling services for women should be developed and standardised within multidisciplinary teams. Pregnant women should be encouraged to attend antenatal classes where PFME is taught practically and knowledge is improved using educational materials and pictures. |

| Tennfjord et al. 2023 [30] | Overall, the entire study population showed insufficient knowledge of POP and UI. A total of 76.7% of nulliparous women had good knowledge of POP, and 74.4% had good knowledge of UI. Only 44.4% of nulliparous women had good knowledge of PFME, and 51.1% had good knowledge of attitudes toward PFME. A total of 93.2% of nulliparous women did not perform PFME. Of the multiparous women, only 41.2% had good knowledge of PFME, and 45.8% had good knowledge of attitudes toward PFME. A total of 92.7% of multiparous women did not perform PFME. After adjusting for all covariates, educational level was significantly associated with better knowledge of PFME (p < 0.001). | Most pregnant women used ANC services throughout their pregnancy. Despite this, study participants’ knowledge of UI and POP was poor, as was their attitude and practice towards PFD, indicating a need to improve the quality of healthcare services. |

| Toprak Celenay et al. 2021 [31] | Overall, the entire study population showed a very low knowledge of POP and UI. The median PIKQ-UI was 6 points, and PIKQ-POP scores were 5 (Scales 0–12). Overall, 92.3% of the included women lacked knowledge regarding UI and 57.5% regarding POP. A total of 18.9% of pregnant women participated in ANE. The median PIKQ-UI and PIKQ-POP scores were higher in women who had attended ANE. A total of 45% of the included pregnant women cited the internet as the main source of information for disseminating knowledge about UI and POP. The healthcare professional doctor (20%) or midwife (8.6%) was less considered a source of information. Pelvic floor disorder during pregnancy was common. Of the included pregnant women, 18.6% had UI and 3.6% had sudden onset of POP. | To promote pelvic floor health, comprehensive prenatal education programs on UI and POP, as well as PMFT by health care professionals, are an essential necessity for all pregnant women. These should not only teach birth and infant care, but also explicitly address the topics of PFM, UI, and POP. Even women who are not pregnant should be informed about PFM, POP, and UI. |

| Yohay et al. 2022 [32] | Overall, the entire study population showed a low knowledge of POP and UI. The average PIKQ scores were 7.65 ± 2.8 and 5.32 ± 2 for UI and POP, respectively. There were significantly higher average scores in UI and POP noted among health care workers (UI: 10.19 ± 2.3 vs. 7.34 ± 2.6, p < 0.001; POP: 8.27 ± 2.7 vs. 4.97 ± 2.6, p < 0.001), age over 35 was associated with significantly higher scores (8.13 ± 2.8 vs. 7.48 ± 2.8; p = 0.008) in PIKQ-UI and (5.75 ± 2.5 vs. 5.19 ± 2.9; p = 0.025) in POP. Women with an academic degree show a significantly higher level in PIKQ-UI and POP (p < 0.001) than those without an academic degree. This also applied to pregnant women with higher incomes (p < 0.001). | Research shows low knowledge of PFD among women in the third trimester of pregnancy in Israel. Pregnancy offers good timing for education and interventions. From this, it can be deduced that targeted educational programs should be created for defined target groups in order to improve knowledge about PFD in the relevant population and thus improve the quality of life of women. |

| Kammers et al. [33] | There is a lack of knowledge about the anatomy and function of the female PFM. Various specific subject areas are reflected in the results. The female body is usually discovered during puberty. A conservative upbringing leads to a lack of knowledge about one’s own femininity/female body/reproductive organs. The pelvic floor is often associated with structures such as the vaginal canal and labia and is less easily imaged. The uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes are known to participants as a complex reproductive system in the lower abdomen and can also be represented graphically. The pelvic floor is less well known as part of the female body; its structure seems hidden from the imagination of the participants and is therefore difficult to represent. | The results of this study show the importance of school and its sex education and health education programs. To maintain sexual health and avoid illnesses or risks related to pregnancy, women need sufficient knowledge about their bodies. It is clear that in many cultures women’s bodies or their sexuality are still not openly discussed, leading to a lack of knowledge. While organs such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus are largely known, other elements such as the pelvic floor and vagina are unknown and hidden and are more likely to be considered shameful. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weinert, K.; Plappert, C.F. Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor and Related Dysfunctions: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080847

Weinert K, Plappert CF. Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor and Related Dysfunctions: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080847

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeinert, Konstanze, and Claudia F. Plappert. 2025. "Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor and Related Dysfunctions: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080847

APA StyleWeinert, K., & Plappert, C. F. (2025). Pregnant Women’s Knowledge of Pelvic Floor and Related Dysfunctions: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(8), 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080847