Designing and Implementing a Customized Questionnaire to Assess the Attitude of Patients with Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The role of physical activity in diabetes management.

- The impact of diabetes mellitus on social relationships.

- The emotional status of diabetic patients.

- The role of diet in metabolic control.

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

- Physical Activity Management;

- Social and Relational Impact;

- Emotional Well-being;

- Dietary Management.

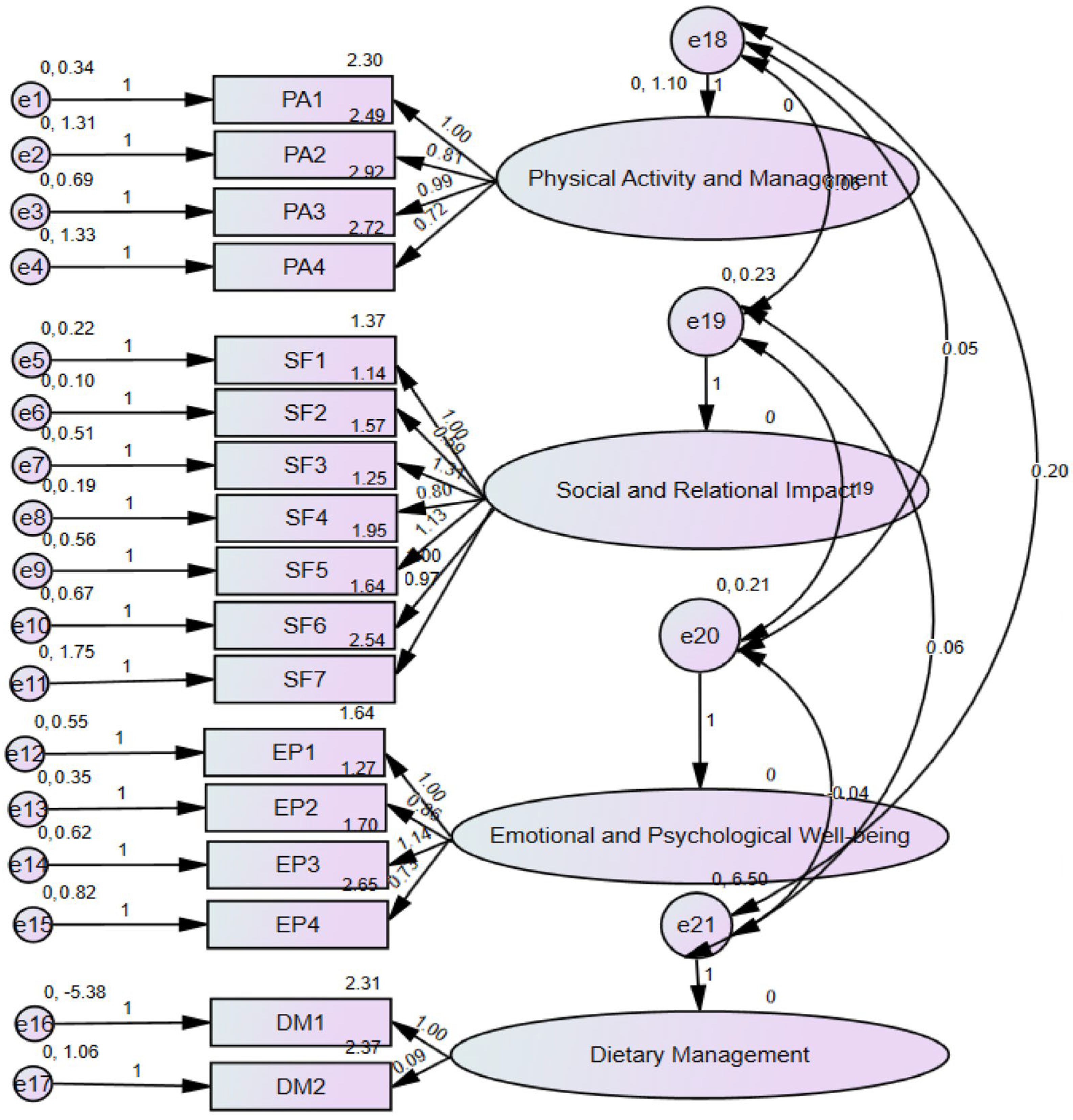

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3. Extracted Factors Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl. S1), S14–S80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, N.; Aqeel, T.; Naseem, A.; Dhingra, S. Assessment of knowledge and dietary misconceptions among diabetic patients. J. Pharm. Pract. Community Med. 2016, 2, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Irshad, M.; Khan, I.; Khan, F.A.; Baig, A.; Gaohar, Q.Y. A survey of awareness regarding diabetes and its management among patients with diabetes in Peshawar, Pakistan. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2015, 28, 372–377. Available online: https://www.jpmi.org.pk/index.php/jpmi/article/view/1628 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Haque, Z.; Javed, A.; Victor, S.; Mehmood, A. Attitudes and behavior of adult Pakistani diabetic population towards their disease. J. Dow Univ. Health Sci. 2014, 8, 89–93. Available online: https://www.jduhs.com/index.php/jduhs/article/view/1423 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Masood, S.N.; Alvi, S.F.D.; Ahmedani, M.Y.; Kiran, S.; Zeeshan, N.F.; Basit, A.; Shera, A.S. Comparison of Ramadan-specific education level in patients with diabetes seen at a primary and a tertiary care center of Karachi, Pakistan. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2014, 8, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenfeld, H.; Mielck, A.; Schumm-Draeger, P.M.; Siegmund, T. How much do inpatient-treated diabetics know about their disease? Gesundheitswesen 2006, 68, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.S.; Hassan, Y.; Aziz, N.A.; Awaisu, A.; Ghazali, R. A comparison of knowledge of diabetes mellitus between patients with diabetes and healthy adults: A survey from north Malaysia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 69, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.A. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1995, 152, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, S.; Nelson, E.C. Recent developments and future issues in the use of health status assessment measures in clinical settings. Med. Care 1992, 30, MS23–MS41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Gahr, A.; Hermanns, N.; Kulzer, B.; Huber, J.; Haak, T. The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): Development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobert, D.J.; Hampson, S.E.; Glasgow, R.E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from seven studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Veldhuyzen Van Zanten, S.J.; Feeny, D.H.; Patrick, D.L. Measuring quality of life in clinical trials: A taxonomy and review. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1989, 140, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs, T.E.; Desikan, R.; Waterman, B.M.; Gilin, D.; McGill, J. Development and validation of the Diabetes Quality of Life Brief Clinical Inventory. Diabetes Spectr. 2004, 17, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, F.R.; Kane, R.L.; Hughes, C.C.; Wright, D. The effects of doctor-patient communication on satisfaction and outcome of care. Soc. Sci. Med. 1978, 12, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.; Speight, J. Patient perceptions of diabetes and diabetes therapy: Assessing quality of life. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2002, 18 (Suppl. S3), S64–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, D.A.; Graboys, T.B.; Johnson, K.; Mordin, M.M.; Goodman, L.; Partsch, D.S.; Goss, T.F. Development and validation of the ITG Health-Related Quality-of-Life Short-Form measure for use in patients with coronary artery disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2001, 24, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The DCCT Research Group. Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Diabetes Care 1988, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Ismail, M.; Mohd Hatta NK, B.; Othman, S.H.; Baharum, N.; Mat Lazim, S.S. Validation of the Malay version of Diabetes Quality of Life (DQOL) Questionnaire for adult population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The DCCT Research Group. Influence of intensive diabetes treatment on quality-of-life outcomes in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 1996, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciberras, J.N.; Galloway, S.D.; Fenech, A.; Grech, G.; Farrugia, C.; Duca, D.; Mifsud, J. The effect of turmeric (Curcumin) supplementation on cytokine and inflammatory marker responses following 2 hours of endurance cycling. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremedhin, T.; Workicho, A.; Angaw, D.A. Health-related quality of life and its associated factors among adult patients with type II diabetes attending Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2019, 7, e000577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonde, T.E.; Ayene, T.R.; Moges, N.A.; Bazezew, Y. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among type 2 diabetic adult patients in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, G.T.; Biratu, S.; Alemayehu, M.; Welie, A.G.; Beyene, K.; Sander, B.; Gebretekle, G.B. Health-related quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at a tertiary care hospital in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Li, J.; Xu, M.; Li, L.; Xu, S.; Fan, X.; Zhu, S.; Chahal, P.; Chattopadhyay, K. Lifestyle behaviors and associated factors among people with type 2 diabetes attending a diabetes clinic in Ningbo, China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantea, I.; Roman, N.; Repanovici, A.; Drugus, D. Diabetes Patients’ Acceptance of Injectable Treatment, a Scientometric Analysis. Life 2022, 12, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, J.; Mokoboto-Zwane, S. Health-related quality of life and domain-specific associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in South India. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2022, 18, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, L.; Faruque, M.; Chowdhury, H.A.; Banik, P.C.; Ali, L. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among the type 2 diabetes population of Bangladesh: A nation-wide cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Sharma, A.; Bhandari, P.M.; Bhochhibhoya, S.; Thapa, K. Depression and health-related quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.H.; Mohd-Sidik, S.; Shariff-Ghazali, S. Negative effects of diabetes-related distress on health-related quality of life: An evaluation among adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in three primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Isworo, A.; Upoyo, A.S.; Taufik, A.; Setiyani, R.; Swasti, K.G.; Haryanto, H.; Yusuf, S.; Nasruddin, N.; Kamaluddin, R. The differences in health-related quality of life between younger and older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indonesia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, D.; Bajko, D.; Lixandru, D.; Mitu, M.; Tudosioiu, J.; Smeu, B.; Copaescu, C.; Ionescu-Tairgoviste, C.; Guja, C. The evolution of resting metabolic rate and body composition after 6 and 12 months of lifestyle changes in obese type 2 diabetes patients. Proc. Rom. Acad. Ser. B 2015, 1, 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin, M.S.; Himeno, T.; Inoue, R.; Miura-Yura, E.; Yamada, Y.; Nakai-Shimoda, H.; Asano, S.; Kato, M.; Motegi, M.; Kondo, M.; et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Protects Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons against Oxidative Insult. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Respondents (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| History of Diabetes in Family | ||

| Yes | 63 | 42 |

| No | 87 | 58 |

| Educational Level | ||

| Primary school | 63 | 42 |

| High School | 52 | 34.67 |

| Faculty | 35 | 23.22 |

| Time since Diabetes diagnostic (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 27 | 18 |

| 5–10 | 54 | 36 |

| 10–15 | 34 | 22.87 |

| 15–20 | 35 | 23.33 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 88 | 58.67 |

| Female | 62 | 41.33 |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has your relationship with your spouse deteriorated due to diabetes? | 0.722 | |||

| How satisfied are you with your social relationships or friendships? | 0.683 | |||

| Is it a burden how others react to the fact that I have diabetes? | 0.673 | |||

| I feel that I am less attractive to others because of my diabetes. | 0.660 | |||

| How often do you feel physically ill? | 0.608 | |||

| How often do you feel that diabetes limits your career? | 0.590 | |||

| How satisfied are you with the time dedicated to physical activity? | 0.546 | |||

| I avoid physical activity even though it improves my diabetes. | 0.826 | |||

| I tend to skip planned physical activity. | 0.792 | |||

| I engage in physical activities regularly to maintain my blood sugar levels. | 0.760 | |||

| I am worried about my future health. | 0.759 | |||

| Because of diabetes, I feel upset/depressed. | 0.814 | |||

| How often do you sleep poorly/are stressed at night due to diabetes? | 0.667 | |||

| I strictly adhere to the nutritional recommendations/diet provided by my doctor. | 0.486 | |||

| The food I choose to eat helps me maintain my blood sugar levels. | 0.841 | |||

| Has your relationship with your spouse deteriorated due to diabetes? | 0.840 |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with the time dedicated to physical activity? | 0.813 | 0.797 | |||

| I avoid physical activity even though it improves my diabetes. | 0.709 | ||||

| I engage in physical activities regularly to maintain my blood sugar levels. | 0.692 | ||||

| I tend to skip planned physical activity. | 0.668 | ||||

| Is it a burden how others react to the fact that I have diabetes? | 0.621 | 0.719 | |||

| Has your relationship with your spouse deteriorated due to diabetes? | 0.616 | ||||

| Is your condition—diabetes—a burden for your family? | 0.595 | ||||

| I feel that I am less attractive to others because of my diabetes. | 0.484 | ||||

| How often do you feel physically ill? | 0.450 | ||||

| How satisfied are you with your social relationships or friendships? | 0.373 | ||||

| Is it a burden to be mindful of what I eat? | 0.233 | ||||

| Because of diabetes, I feel upset/depressed. | 0.510 | 0.669 | |||

| How often do you feel that diabetes limits your career? | 0.467 | ||||

| How often do you sleep poorly/are stressed at night due to diabetes? | 0.430 | ||||

| I am worried about my future health. | 0.279 | ||||

| The food I choose to eat helps me maintain my blood sugar levels. | 0.774 | 0.693 | |||

| I strictly adhere to the nutritional recommendations/diet provided by my doctor. | 0.677 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Repanovici, A.; Pantea, I.; Roman, N.A. Designing and Implementing a Customized Questionnaire to Assess the Attitude of Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070815

Repanovici A, Pantea I, Roman NA. Designing and Implementing a Customized Questionnaire to Assess the Attitude of Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070815

Chicago/Turabian StyleRepanovici, Angela, Ileana Pantea, and Nadinne Alexandra Roman. 2025. "Designing and Implementing a Customized Questionnaire to Assess the Attitude of Patients with Diabetes" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070815

APA StyleRepanovici, A., Pantea, I., & Roman, N. A. (2025). Designing and Implementing a Customized Questionnaire to Assess the Attitude of Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare, 13(7), 815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070815