Parental Perceptions About Energy Balance Related Behaviors and Their Determinants Among Children and Adolescents Living with Disability: A Qualitative Study in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Procedure and Ethical Approval

2.4. Data Collection Approach and Materials

2.5. Analysis

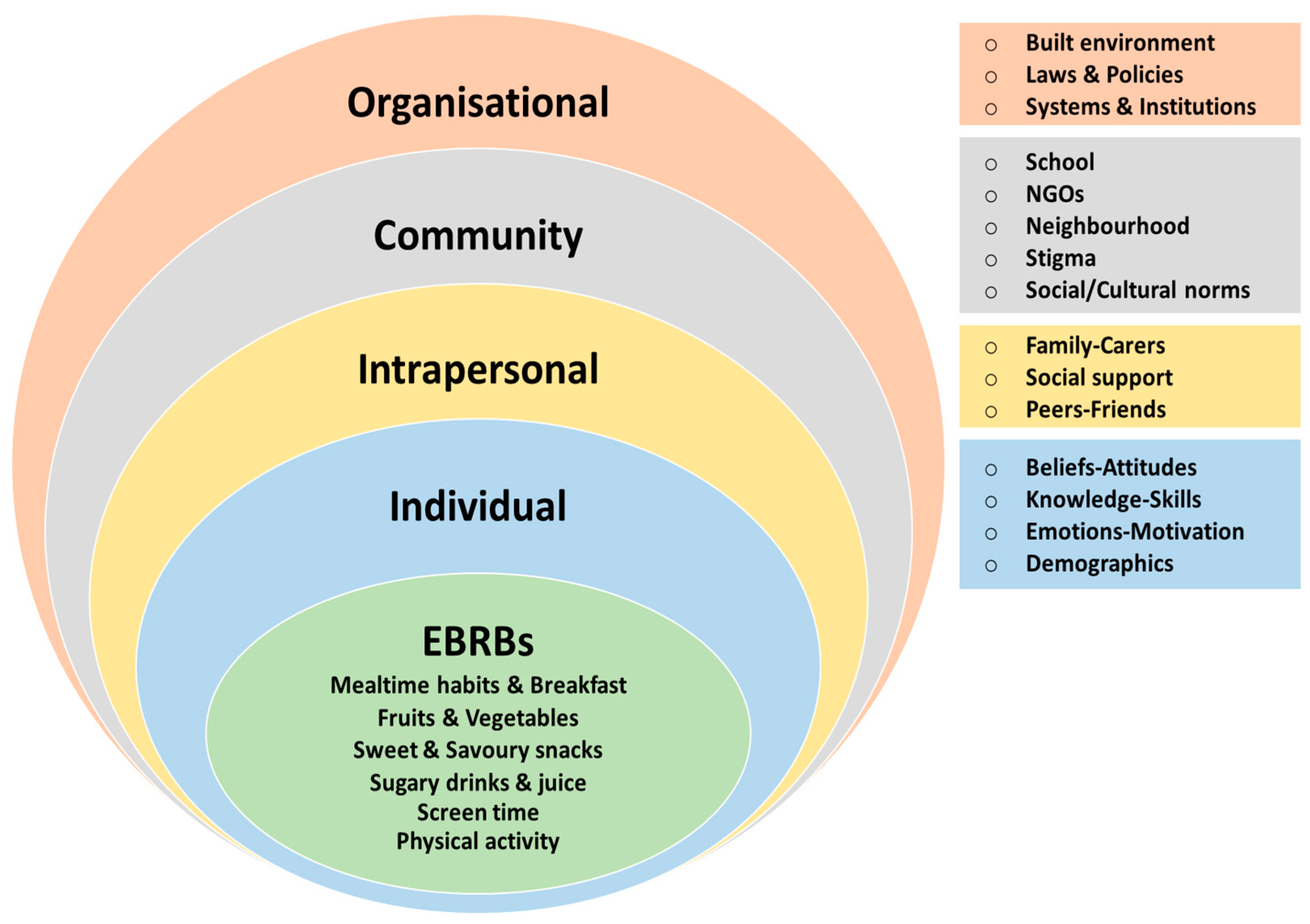

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Themes

- Theme 1: Key EBRBs

“He eats breakfast every day. We don’t go anywhere without breakfast.”

“And with sweets, it’s the same (as with savory snacks). I make cookies and cakes, banana bread, generally various treats, apple pies, and so on.”

“Q: So, there isn’t a physical education class or any activity at school for him to release his energy?

A: No, except for when we do therapy and another game we do with basic equipment like a ball.”

“He spends quite a bit of time on screens—on a mobile phone, tablet, or even watching TV. Recently, however, we’ve limited our screen time a bit, and during the week he doesn’t watch any kids’ shows on the phone or on TV. He watches on weekends instead, and it might be 2 or 3 h over the weekend.”

- Theme 2: Behavioral determinants of key EBRBs, individual level antecedents

“As for vegetables, he prefers them mostly cooked in his meals. From salads, he mainly eats cucumbers raw. For other vegetables, he eats everything cooked. In general, yes, due to texture, colors, and so on, we don’t eat much raw, but generally, we eat them cooked.”

- Theme 3: Behavioral determinants of key EBRBs, interpersonal level antecedents

“If we have any other food options in the cupboard, he’ll prefer those. So, many times I avoid having those things around to encourage us to eat something healthier. Because I know if there’s something like chocolate, chocolate spreads, jam, or something else in the house, he’ll choose that over fruit. But if there’s no other choice, he’ll eat the fruit; it’s not that he won’t eat it.”

“A: We all drink soft drinks at home, but not juice.

Q: And the soft drinks you have at home, are they usually with sugar or without?

A: No, they’re the regular ones with sugar.”

“You’re asking about the support we receive—or don’t receive—for nutrition! Here, the support for other, perhaps more critical and essential aspects of disability is nonexistent! We receive a monthly allowance! Do you know how much the equipment costs? Do you know how much occupational therapy costs? Physical therapy? The daycare center for children living with disability? The reason we don’t go to public services is that there are serious issues there.”

“One child will get jealous of the other; I see it when my nephew comes over, and I serve food—he imitates. He copies what the other is doing. Or he’ll say, ‘I want some too, what does the other kid have?’ or ‘Who’s going to eat faster?’ or ‘The spoon moves quickly; he doesn’t sit there getting bored, saying, I don’t want this, I don’t want that’”

“Of course, even if you go, since it’s not a playground for children living with disability, other kids always have difficulty accepting (name of child), and countless times they have mocked him. Generally, he doesn’t really want to go because it ruins his mood!”

- Theme 4: Behavioral determinants of key EBRBs, community level antecedents

“Of course, children should at least be informed about the food groups they should be consuming throughout the week. Learning about the food pyramid is one thing, but the real issue is what actually happens in practice.”

“Because the first thing is to know, to be aware. They don’t know! They may graduate from a school, but we haven’t seen people, let’s say, who are not just incapable of helping, they simply don’t know. For example, I know more as a father who has read about autism than the person who has studied something.”

“When the school itself doesn’t teach proper nutrition within its own environment with what it sells, how can we expect anything different?”

- Theme 5: Behavioral determinants of key EBRBs, organizational level antecedents

“Sidewalks are nonexistent, ramps are blocked by cars! You can’t go out with your child in a wheelchair! And don’t even mention playgrounds with special swings! Our children don’t get to play!”

“And, you know, he couldn’t fit in with the group because many kids made fun of him, so he would always come back upset, angry, or anxious, and we ended up stopping the visits.”

“They used it at the beginning, even our therapists—when he performed a correct exercise or responded to the communication requirements at that specific moment, he would get a small piece of chocolate.”

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBRBs | Energy Balance Related Behaviors |

References

- Di Cesare, M.; Sorić, M.; Bovet, P.; Miranda, J.J.; Bhutta, Z.; Stevens, G.A.; Laxmaiah, A.; Kengne, A.P.; Bentham, J. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: A worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative COSI—Fact Sheet Highlights 2018–2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/m/item/childhood-obesity-surveillance-initiative-cosi-fact-sheet-highlights-2018-2020 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Heath Survey 2019, Health of Children 2 to 14 Years. Press Release. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/008dbe0e-e7a7-c45b-b502-56d0cffd46c8 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability and Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/disability-and-health/conditions/obesity.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Unicef Greece. Education Access and Participation in Greece. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/greece/en/state-childrens-rights/education/education-access-and-participation (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- National Centre For Social Solidarity (Greece), Hellenic Republic Ministry of Social Cohesion and Family Affairs. National Action Plan for the “European Child Guarantee”. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=26063&langId=en (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Must, A.; Curtin, C.; Hubbard, K.; Sikich, L.; Bedford, J.; Bandini, L. Obesity Prevention for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halilagic, A.; Roussos, R.; Argyropoulou, M.; Svolos, V.; Mavrogianni, C.; Androutsos, O.; Mouratidou, T.; Manios, Y.; Moschonis, G. Interventions to promote healthy nutrition and lifestyle and to tackle overweight and obesity amongst children in need in Europe: A rapid literature review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1517736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinehr, T.; Dobe, M.; Winkel, K.; Schaefer, A.; Hoffmann, D. Obesity in disabled children and adolescents: An overlooked group of patients. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Mirizzi, P.; Fadda, R.; Pirollo, C.; Ricciardi, O.; Mazza, M.; Valenti, M. Food Selectivity in Children with Autism: Guidelines for Assessment and Clinical Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, M.K.; Caccavale, L.J.; Adams, E.L.; Burnette, C.B.; LaRose, J.G.; Raynor, H.A.; Wickham, E.P., 3rd; Mazzeo, S.E. Parent Involvement in Adolescent Obesity Treatment: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarty, A.M.; Melville, C.A. Parental perceptions of facilitators and barriers to physical activity for children with intellectual disabilities: A mixed methods systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 73, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, K.Y. Overprotection and lowered expectations of persons with disabilities: The unforeseen consequences. Work 2006, 27, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaine, R.E.; Kachurak, A.; Davison, K.K.; Klabunde, R.; Fisher, J.O. Food parenting and child snacking: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, L.; Marks, D.F. Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; DeLia, D.; DeWeese, R.S.; Crespo, N.C.; Todd, M.; Yedidia, M.J. The relative contribution of layers of the Social Ecological Model to childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, S.A.; Curtin, C.; Bandini, L.G. Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreck, K.A.; Williams, K. Food preferences and factors influencing food selectivity for children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, A.; Halilagic, A.; Argyropoulou, M.; Siopis, G.; Roussos, R.; Svolos, V.; Mavrogianni, C.; Androutsos, O.; Mouratidou, T.; Manios, Y.; et al. The Role of Energy Balance-Related Behaviors (EBRBs) and their Determinants on the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children in Need, in Greece: A Scoping Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouka, A.; Brikou, D.; Causeret, C.; Al Ali Al Malla, N.; Sibalo, S.; Ávila, C.; Alcat, G.; Kapetanakou, A.E.; Gurviez, P.; Fellah-Dehiri, N.; et al. Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions in Europe for Promoting Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors in Children. Children 2023, 10, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C.; McCrabb, S.; Stacey, F.; Nathan, N.; Yoong, S.L.; Grady, A.; Sutherland, R.; Hodder, R.; Innes-Hughes, C.; Davies, M.; et al. Improving implementation of school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs: A systematic review. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1365–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A.J.; Barr, M. Perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity for children with disability: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.J. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: A social-relational model of disability perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, U.A.; Nishida, A.; Fletcher, F.E.; Molina, Y. The Long Arm of Oppression: How Structural Stigma Against Marginalized Communities Perpetuates Within-Group Health Disparities. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balafouti, T.; Roussos, R.; Argyropoulou, M.; Svolos, V.; Mavrogianni, C.; Mannino, A.; Moschonis, G.; Androutsos, O.; Manios, Y.; Mouratidou, T. A Policy-Driven Scoping Review of the Regulatory and Operational Framework Addressing Obesity in Children in Need in Greece. Child. Soc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic Guide for Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews with Parents/Caregivers of Children Living with Disability |

|---|

| 1. Would you like to tell me about the role of fruit and vegetables in the diet of your child? |

| 2. Let’s now discuss a different category of food: savory and sweet snacks. By “savory snacks”, we usually refer to foods that are high in salt and are eaten before or after the main meals (e.g., crisps, savory crackers, cheese pie). Similarly, the term “sweet snacks” refers to foods that are high in sugar and are consumed before or after the main meals (e.g., chocolate, cakes, croissants, biscuits). Do you wish to talk to me about the role of savory and sweet snacks in the diet of your child? |

| 3. How about discussing the consumption of sugary drinks and juices? What do you think about the consumption of your child? |

| 4. Breakfast is the first meal of the day, eaten up to 2 h after waking up. What is the role of breakfast in the diet of your child? |

| 5. Would you like to tell me about the mealtime habits of your family? |

| 6. For some households, the economic situation can affect the eating habits of the family, and in particular of the children. What is your opinion? |

| 7. Do you receive support and guidance from the government or other organizations to help your child adopt healthy eating habits (e.g., health promotion/information activities on healthy eating at school, in daycare centers, financial assistance)? If so, from which organizations? What could help you in this regard? |

| 8. Some people think that school could help promote healthy eating among children. What is your opinion? |

| 9. Another important behavior, related to the lifestyle of children, is the use of screens. Screen use is defined as the time spent using an electronic device, such as a mobile phone, computer, tablet, PlayStation, etc. Tell me about the role of these activities in the daily life of your child. |

| 10. Now, let’s talk about physical activity. By physical activity, we refer to activities during which the body moves, such as when playing sports or walking. What is the role of physical activity in the daily life of your child? |

| Parents/Caregivers of Children Living with Disability | |

|---|---|

| Number of participants (N) | 45 |

| Age (in years) | |

| Median (IQR) | 44 (41, 51) |

| Gender N (%) | |

| Men | 4 (9%) |

| Women | 41 (91%) |

| Area of residence N (%) | |

| Attica | 15 (33%) |

| Thessaly | 15 (33%) |

| Crete | 15 (33%) |

| Level of education N (%) | |

| Doctoral studies | 0 (0%) |

| Postgraduate studies | 4 (9%) |

| University | 19 (42%) |

| Postsecondary education | 13 (29%) |

| High school | 9 (20%) |

| Junior high school | 0 (0%) |

| Employment N (%) | |

| Full-time | 25 (56%) |

| Part-time | 4 (9%) |

| Unemployed | 16 (36%) |

| Child’s age (in years) | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (7, 15) |

| Gender of child N (%) | |

| Boy | 29 (64%) |

| Girl | 16 (36%) |

| Child’s disability type N (%), including multiple diagnoses | |

| ASDs | 25 (56%) |

| Cerebral palsy | 11 (24%) |

| Intellectual disability | 4 (9%) |

| Loss of vision | 2 (4%) |

| Cri du chat syndrome | 1 (2%) |

| Down’s syndrome | 1 (2%) |

| Dravet syndrome | 1 (2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Svolos, V.; Strongylou, D.E.; Argyropoulou, M.; Stamathioudaki, A.M.; Michailidou, N.; Balafouti, T.; Roussos, R.; Mavrogianni, C.; Mannino, A.; Moschonis, G.; et al. Parental Perceptions About Energy Balance Related Behaviors and Their Determinants Among Children and Adolescents Living with Disability: A Qualitative Study in Greece. Healthcare 2025, 13, 758. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070758

Svolos V, Strongylou DE, Argyropoulou M, Stamathioudaki AM, Michailidou N, Balafouti T, Roussos R, Mavrogianni C, Mannino A, Moschonis G, et al. Parental Perceptions About Energy Balance Related Behaviors and Their Determinants Among Children and Adolescents Living with Disability: A Qualitative Study in Greece. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):758. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070758

Chicago/Turabian StyleSvolos, Vaios, Dimitra Eleftheria Strongylou, Matzourana Argyropoulou, Anna Maria Stamathioudaki, Nina Michailidou, Theodora Balafouti, Renos Roussos, Christina Mavrogianni, Adriana Mannino, George Moschonis, and et al. 2025. "Parental Perceptions About Energy Balance Related Behaviors and Their Determinants Among Children and Adolescents Living with Disability: A Qualitative Study in Greece" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 758. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070758

APA StyleSvolos, V., Strongylou, D. E., Argyropoulou, M., Stamathioudaki, A. M., Michailidou, N., Balafouti, T., Roussos, R., Mavrogianni, C., Mannino, A., Moschonis, G., Mouratidou, T., Manios, Y., & Androutsos, O. (2025). Parental Perceptions About Energy Balance Related Behaviors and Their Determinants Among Children and Adolescents Living with Disability: A Qualitative Study in Greece. Healthcare, 13(7), 758. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070758

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)