Social Capital and Depression Among Adolescents Relocated for Poverty Alleviation: The Mediating Effect of Life Satisfaction

Abstract

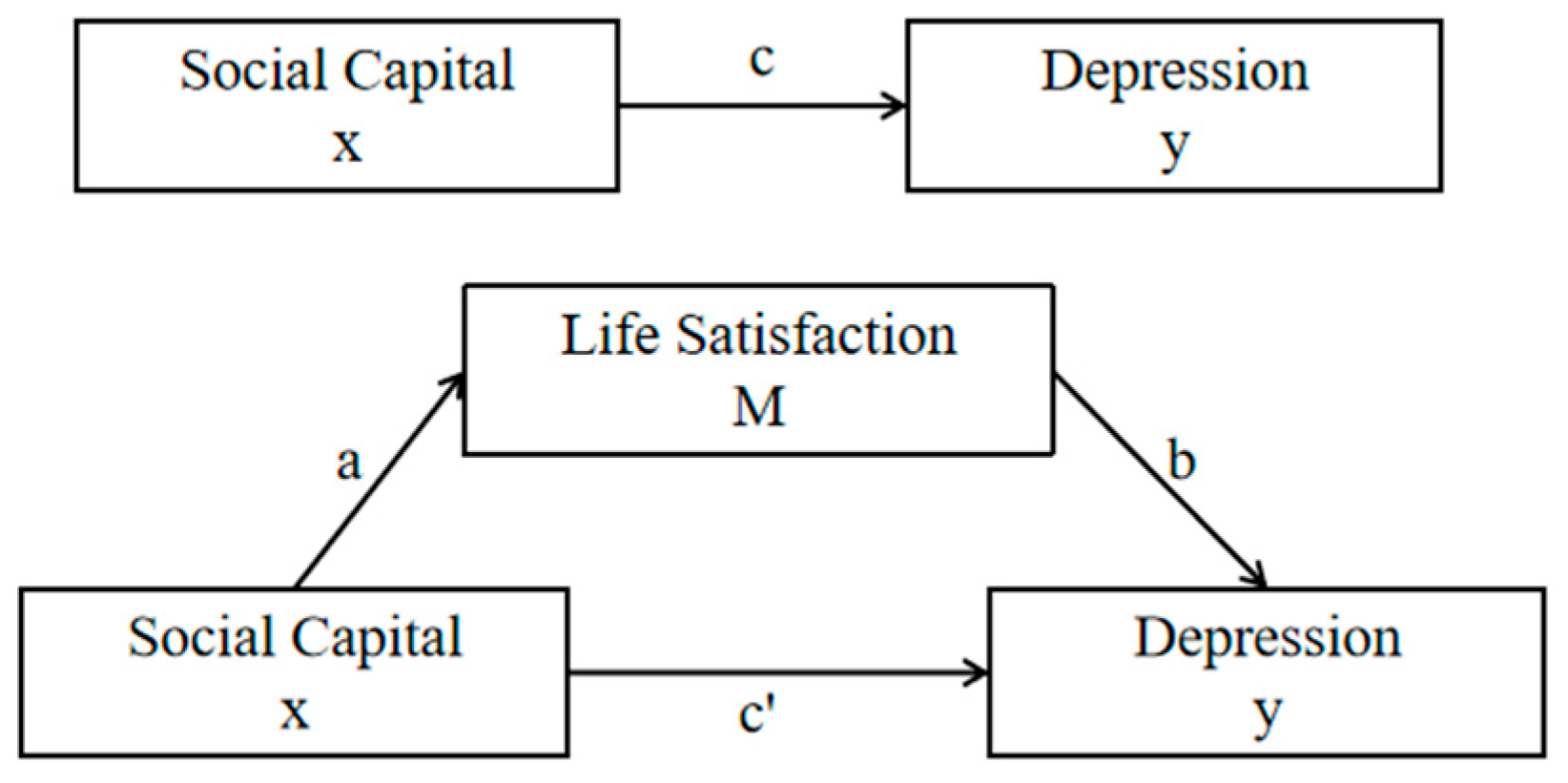

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.2. Background of China’s Poverty Alleviation Policy

1.3. Research Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

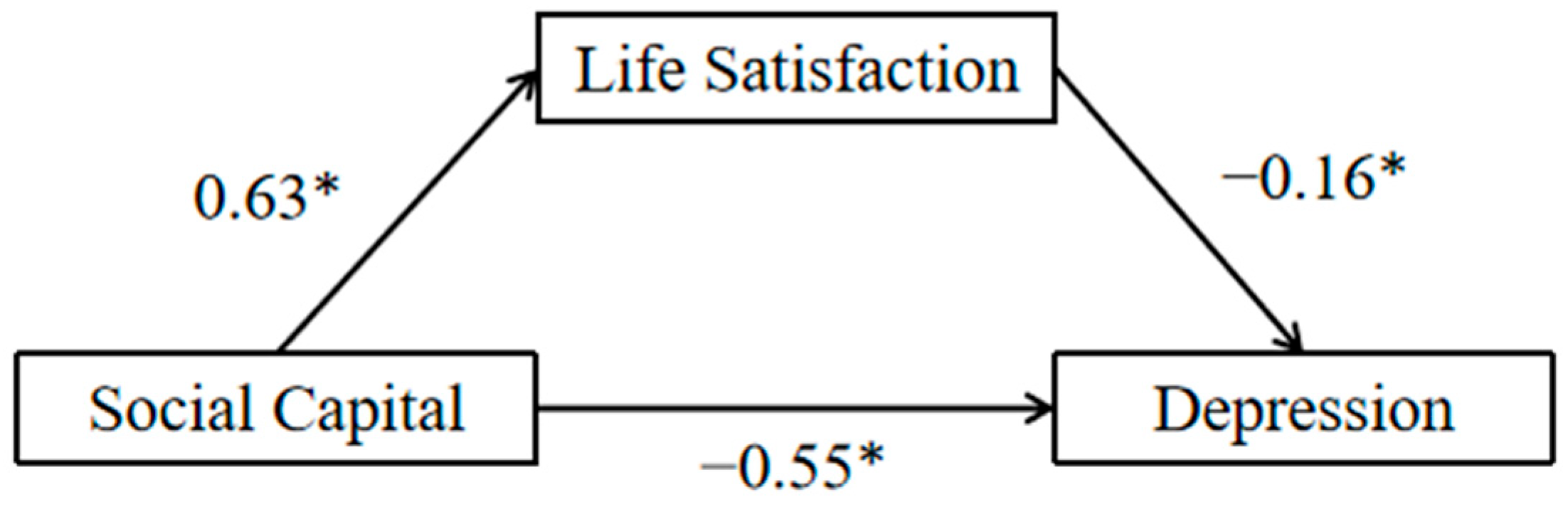

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale |

| SCQ-AS | Social Capital Questionnaire for Adolescent Students |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Amminger, G.P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Üstün, T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiat. 2007, 20, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.E.; Moonajilin, M.S.; van Os, J. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and associated factors among school going adolescents in Bangladesh: Findings from a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Usha, V.K. Prevalence and Predictors of Depression Among Adolescents. Indian J. Pediatr. 2021, 88, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L. Blue Book of Youth Development: Report on Youth Development in China; Social Science Literature Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 126–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw, S. Annual research review: Secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 3, 370–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini-Esfidarjani, S.S.; Tanha, K.; Negarandeh, R. Satisfaction with life, depression, anxiety, and stress among adolescent girls in Tehran: A cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice: Summary Report/A Report from the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T.C. What percentage of people in Europe are flourishing and what characterises them? In Proceedings of the OECD/ISQOLS Meeting “Measuring Subjective WellBeing: An Opportunity for NSOs?”, Florence, Italy, 23–24 July 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Xiao, T.; Lyu, S.; Zhao, R. The Relationship Between Social Capital and Depressive Symptoms Among the Elderly in China: The Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meng, T.; Chen, H. A multilevel analysis of social capital and self-rated health: Evidence from China. Health Place 2014, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Lu, N. Community-based cognitive social capital and self-rated health among older chinese adults: The moderating effects of education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Subramanian, S.V.; Mitchell, A.D.; Lee, D.T.S.; Wang, J.; Kawachi, I. Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Fan, G.; Shen, G. The income disparity, the social capital and health: A case study based on China family panel studies. Manag. World 2014, 30, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Lee, S.H.; Rhee, H.S. Developmental trajectory and relationships between Adolescents’ social capital, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms: A latent growth model. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijs, T.; Maes, L.; Salonna, F.; Van Damme, J.; Hublet, A.; Kebza, V.; Costongs, C.; Currie, C.; De Clercq, B. The role of community social capital in the relationship between socioeconomic status and adolescent life satisfaction: Mediating or moderating? Evidence from Czech data. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, A.M.; Guhn, M.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Hymel, S.; Thomson, K.; Hertzman, C. A population-based study of children’s well-being and health: The relative importance of social relationships, health-related activities, and income. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1847–1872. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, P.E.; Kashdan, T.B. The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: A case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Ren, S. Social integration problems of children relocated for poverty alleviation and their educational support. Contemp. Youth Res. 2021, 71–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Zou, W.; Wang, H. School adaptation and adolescent immigrant mental health: Mediation of positive academic emotions and conduct problems. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 967691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delaruelle, K.; Walsh, S.D.; Dierckens, M.; Deforche, B.; Kern, M.R.; Currie, C.; Maldonado, C.M.; Cosma, A.; Stevens, G.W.J.M. Mental Health in Adolescents with a Migration Background in 29 European Countries: The Buffering Role of Social Capital. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunduma, G.; Deyessa, N.; Dessie, Y.; Geda, B.; Yadeta, T.A. High Social Capital is Associated with Decreased Mental Health Problem Among In-School Adolescents in Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, E.; Song, M.K. Profiles of Social Capital and the Association with Depressive Symptoms Among Multicultural Adolescents in Korea: A Latent Profile Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 794729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, M.J.; Liechty, J.M. Longitudinal Associations Between Immigrant Ethnic Density, Neighborhood Processes, and Latino Immigrant Youth Depression. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyncke, V.; De Clercq, B.; Stevens, V.; Costongs, C.; Barbareschi, G.; Jónsson, S.H.; Curvo, S.D.; Kebza, V.; Currie, C.; Maes, L. Does neighbourhood social capital aid in levelling the social gradient in the health and well-being of children and adolescents? A literature review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potochnick, S.R.; Perreira, K.M. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: Key correlates and implications for future research NIH public access. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health Care Providers; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lobvibnd, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, P.C.P.; de Paiva, H.N.; de Oliveira Filho, P.M.; Lamounier, J.A.; Ferreira, E.F.E.; Ferreira, R.C.; Kawachi, I.; Zarzar, P.M. Development and Validation of a Social Capital Questionnaire for Adolescent Students (SCQ-AS). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern, J.; Rodriguez, D.; Kassel, J.D. Adolescent smoking and depression: Evidence for self-medication and peer smoking mediation. Addiction 2009, 104, 1743–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, S.; Dumornay, N.M. Rising Rates of Adolescent Depression in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities in the 2020s. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 354–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J. Mediation effect test procedure and its application. Psychol. J. 2004, 36, 614–620. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov, C. Social capital and happiness in the United States. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2008, 3, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C. Social Capital or Social Cohesion: What Matters for Subjective Well-Being (SWB)? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 891–911. [Google Scholar]

- Al Khatib, S.A. Satisfaction with life, self-esteem, gender and marital status as predictors of depressive symptoms among United Arab Emirates college students. Int. J. Psychol. Counsell. 2013, 5, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Okwaraji, F.E.; Aguwa, E.N.; Shiweobi-Eze, C. Life satisfaction, self-esteem and depression in a sample of Nigerian adolescents. Int. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. J. 2016, 5, 2321–7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.; Li, X. Perceived school performance, life satisfaction, and hopelessness: A 4-year longitudinal study of adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Espnes, G.A. Self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents gender and age as potential moderators. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Trends in Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Parent-Child Communication. Master’s Thesis, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandal, R.K.; Goel, N.K.; Sharma, M.K.; Bakshi, R.K.; Singh, N.; Kumar, D. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among school going adolescent in Chandigarh. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2017, 6, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Khess, C.R. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young male adults in India: A dimensional and categorical diagnoses-based study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-G. Effects of interpersonal relationships on depression: Chain-mediated effects of life satisfaction and meaning of life. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 30, 1459–1463. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.; Corwyn, R. Life satisfaction among european american, african american, chinese american, mexican american, and dominican american adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, L. Depression and life satisfaction among European and Confucian adolescents. Psychol. Assess 2013, 25, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar]

- De Vasconcelos, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.; Reis, D.; Couto, I.; Sena, C.; Botelho, A.C.; Bonavides, D.; Hemanny, C.; Seixas, C.; Zeni, C.P.; et al. Life satisfaction mediates the association between childhood maltreatment and depressive symptoms: A study in a sample of Brazilian adolescents. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahoney, J.W.; Quested, E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Ntoumanis, N.; Gucciardi, D.F. Validating a measure of life satisfaction in older adolescents and testing in variance across time and gender. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A. Relationship between life satisfaction and depression among working and non-working married women. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Res. 2016, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, K.E.; Kerr, S.; McGee, E.; Morgan, A.; Cheater, F.M.; McLean, J.; Egan, J. The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: An integrative systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2014, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prins, R.G.; Oenema, A.; Van DH, K. Objective and perceived availability of physical activity opportunities: Differences in associations with physical activity behavior among adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Physic. Act. 2009, 6, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jaric, I.; Rocks, D.; Cham, H.; Herchek, A.; Kundakovic, M. Sex and estrous cycle effects on anxiety-and depression-related phenotypes in a two-Hit developmental stress model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J.M.; Shaw, D.S. Examining Parental Monitoring, Neighborhood Peer Anti-social Behavior, and Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Control as a Pathway to Adolescent Substance Use. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 626–639. [Google Scholar]

- King, C.; Huang, X.; Dewan, N.A. Continuity and change in neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent depression and anxiety. Health Place 2022, 73, 102724. [Google Scholar]

- Salvy, S.J.; de la Haye, K.; Bowker, J.C.; Hermans, R.C. Influence of peers and friends on children’s and adolescents’ eating and activity behaviors. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Popa, M.D.; Sharma, A.; Kundnani, N.R.; Gag, O.L.; Rosca, C.I.; Mocanu, V.; Tudor, A.; Popovici, R.A.; Vlaicu, B.; Borza, C. Identification of Heavy Tobacco Smoking Predictors-Influence of Marijuana Consuming Peers and Truancy among College Students. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarrani, A.; Hunter, R.; Dunne, L.; Garcia, L. Association between friendship quality and subjective wellbeing in adolescents: A cross-sectional observational study. Lancet 2023, 402 (Suppl. 1), S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothon, C.; Goodwin, L.; Stansfeld, S. Family social support, community “social capital” and adolescents’ mental health and educational outcomes: A longitudinal study in England. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levin, K.A.; Torsheim, T.; Vollebergh, W.; Richter, M.; Davies, C.A.; Schnohr, C.W.; Due, P.; Currie, C. National Income and Income Inequality, Family Affluence and Life Satisfaction Among 13 year Old Boys and Girls: A Multilevel Study in 35 Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J. Socioeconomic Status, Family Processes, and Individual Development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steare, T.; Lewis, G.; Lange, K.; Lewis, G. The association between academic achievement goals and adolescent depressive symptoms: A prospective cohort study in Australia. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 2024, 8, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. How Does East Asian Culture Affect Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction? Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjing, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Lohre, A.; Lillefjell, M.; Byrne, D.G.; Haugan, G. The association between school stress, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Life satisfaction as a potential mediator. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Boy | 315 | 49.9 |

| Girl | 316 | 50.1 | |

| Age (years) | 10–13 | 347 | 55.0 |

| 14–16 | 153 | 24.2 | |

| 17–19 | 131 | 20.8 | |

| Only child | Yes | 90 | 14.3 |

| No | 541 | 85.7 | |

| Father’s education | Elementary school | 225 | 35.66 |

| Middle school | 307 | 48.65 | |

| High school | 69 | 10.94 | |

| College and above | 30 | 4.75 | |

| Mather’s education | Elementary school | 205 | 32.49 |

| Middle school | 312 | 49.45 | |

| High school | 78 | 12.36 | |

| College and above | 36 | 5.71 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 17 | 2.7 |

| No | 614 | 97.3 | |

| Alcohol | Yes | 15 | 2.4 |

| No | 616 | 97.6 | |

| Outdoor exercise | Yes | 455 | 72.1 |

| No | 176 | 27.9 |

| ± S | Life Satisfaction | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social capital (total) | 31.96 ± 3.666 | 0.363 * | −0.362 * |

| School cohesion | 10.71 ± 1.732 | 0.366 * | −0.345 * |

| School friendship | 8.39 ± 1.141 | 0.214 * | −0.302 * |

| Neighborhood social cohesion | 5.15 ± 1.190 | 0.191 * | −0.228 * |

| Trust | 7.71 ± 1.466 | 0.139 * | −0.086 * |

| Life satisfaction | 23.21 ± 6.282 | 1 | −0.398 * |

| Depression | 4.03 ± 5.503 | −0.398 * | 1 |

| Variables | Step 1-c | Step 2-a | Step 3-b | Step 3-c′ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social capital (total) | β | −0.55 * | 0.63 * | −0.16 * | −0.44 * |

| R2 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.17 | ||

| F | 97.00 * | 91.80 * | 62.13 * | ||

| p | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ||

| School cohesion | β | −1.09 * | 1.37 * | −0.17 * | −0.87 * |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | ||

| F | 85.23 * | 97.17 * | 56.60 * | ||

| p | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ||

| School friendship | β | −1.45 * | 1.22 * | −0.21 * | −1.20 * |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.15 | ||

| F | 63.32 * | 30.08 * | 54.45 * | ||

| p | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | β | −1.05 * | 1.04 * | −0.22 * | −0.82 * |

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.12 | ||

| F | 34.39 * | 23.75 * | 42.12 * | ||

| p | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ˂0.001 | ||

| Trust | β | −0.32 * | 0.62 * | −0.17 * | −0.24 * |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||

| F | 4.66 * | 12.42 * | 31.02 * | ||

| p | 0.0313 | 0.0005 | ˂0.001 | ||

| Variables | Mediating Effect | Bootstrap 95% CI | Proportion of the Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Social capital (total) | −0.1008 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 18.20% |

| School cohesion | −0.2329 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 21.37% |

| School friendship | −0.2562 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 17.67% |

| Neighborhood social cohesion | −0.2288 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 21.79% |

| Trust | −0.1054 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 32.94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q. Social Capital and Depression Among Adolescents Relocated for Poverty Alleviation: The Mediating Effect of Life Satisfaction. Healthcare 2025, 13, 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070743

Guo D, Yang L, Wang L, Yu Q. Social Capital and Depression Among Adolescents Relocated for Poverty Alleviation: The Mediating Effect of Life Satisfaction. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):743. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070743

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Dan, Le Yang, Li Wang, and Qi Yu. 2025. "Social Capital and Depression Among Adolescents Relocated for Poverty Alleviation: The Mediating Effect of Life Satisfaction" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070743

APA StyleGuo, D., Yang, L., Wang, L., & Yu, Q. (2025). Social Capital and Depression Among Adolescents Relocated for Poverty Alleviation: The Mediating Effect of Life Satisfaction. Healthcare, 13(7), 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070743