The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Cognitive Ability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mediating Effect of Social Participation and Social Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Socioeconomic Factors and Cognition

1.2. The Mediating Role of Social Participation and Social Support

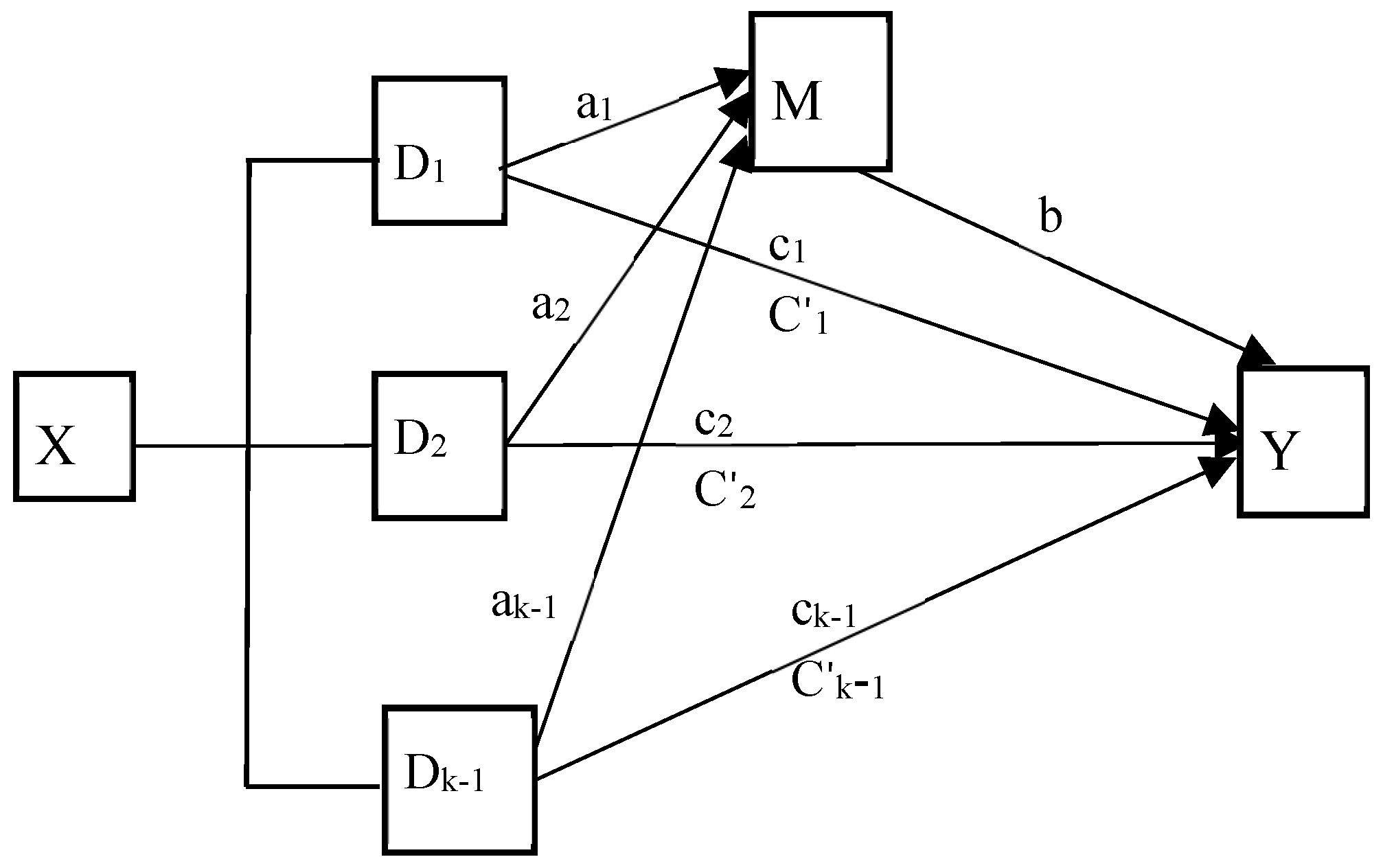

1.3. The Conceptual Model of Present Study

- Socioeconomic conditions (income, occupation, and education) are directly associated with cognitive function (i.e., high levels of socioeconomic conditions are directly positively related to high levels of cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults (H1)).

- Social support mediates the relationship between socioeconomic factors and cognitive function (i.e., high levels of socioeconomic conditions are significantly associated with high levels of social support (H2), which are significantly associated with high levels of cognitive function (H5)).

- Social participation mediates the relationship between socioeconomic factors and cognitive function (i.e., high levels of socioeconomic conditions are significantly associated with high levels of social participation (H3), which are significantly associated with high levels of cognitive function (H6)).

- 4.

- Social support mediates the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and cognitive function, which in turn is mediated by social participation (i.e., high levels of socioeconomic conditions lead to high levels of social support, which in turn lead to high levels of social participation, and ultimately lead to high levels of cognitive function (path from H2, H4, to H6)).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cognitive Function

2.2.2. Socioeconomic Factors

2.2.3. Social Participation and Social Support

2.2.4. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis for the Study Variables

3.3. Mediation Effect Analysis

3.3.1. Omnibus Mediation Effect Analysis

3.3.2. Relative Mediation Effect of Social Participation or Social Support

3.3.3. Relative Seral Mediating Effect of Social Support and Social Participation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mobaderi, T.; Kazemnejad, A.; Salehi, M. Exploring the impacts of risk factors on mortality patterns of global Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, W.J.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Q. Aging tsunami coming: The main finding from China’s seventh national population census. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, N.; Li, Z.; Lv, D.; Wang, H.; Jin, J.; Wen, X.; Zhao, S.; Xu, T.; et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in Chinese older inpatients and its relationship with 1-year adverse health outcomes: A multi-center cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cigolle, C.T.; Langa, K.M.; Kabeto, M.U.; Tian, Z.; Blaum, C.S. Geriatric conditions and disability: The Health and Retirement Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Sucari, H.C.; Rodríguez-Eguizabal, J.L. Cognitive health in older adults, a public health challenge. Gac. Medica Mex. 2024, 160, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.R.; Deary, I.J. Brain and cognitive ageing: The present, and some predictions (…about the future). Aging Brain 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhuis, E.J.; Slade, K.; May, P.J.C.; Nuttall, H.E. Toward an Understanding of Healthy Cognitive Aging: The Importance of Lifestyle in Cognitive Reserve and the Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2023, 78, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; Park, D.C. Cognitive aging and the life course: A new look at the Scaffolding theory. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2024, 56, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Hendrie, K.; Jester, D.J.; Dasarathy, D.; Lavretsky, H.; Ku, B.S.; Leutwyler, H.; Torous, J.; Jeste, D.V.; Tampi, R.R. Social connections as determinants of cognitive health and as targets for social interventions in persons with or at risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: A scoping review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeycutt, A.A.; Khavjou, O.A.; Tayebali, Z.; Dempsey, M.; Glasgow, L.; Hacker, K. Cost-Effectiveness of Social Determinants of Health Interventions: Evaluating Multisector Community Partnerships’ Efforts. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Miller, G.E. Socioeconomic status and health: Mediating and moderating factors. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 723–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, D.J.; Kohn, J.N.; Tibiriçá, L.; Thomas, M.L.; Brown, L.L.; Murphy, J.D.; Jeste, D.V. Differences in Social Determinants of Health Underlie Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Psychological Health and Well-Being: Study of 11,143 Older Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2023, 180, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusmaully, J.; Dugravot, A.; Moatti, J.P.; Marmot, M.G.; Elbaz, A.; Kivimaki, M.; Sabia, S.; Singh-Manoux, A. Contribution of cognitive performance and cognitive decline to associations between socioeconomic factors and dementia: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.M.; Sutin, A.R.; Atherton, O.E.; Robins, R.W. Are trajectories of personality and socioeconomic factors prospectively associated with midlife cognitive function? Findings from a 12-year longitudinal study of Mexican-origin adults. Psychol. Aging 2023, 38, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.J.; Brodtmann, A.; Irish, M.; Mowszowski, L.; Radford, K.; Naismith, S.L.; Mok, V.C.; Kiernan, M.C.; Halliday, G.M.; Ahmed, R.M. Risk factors for the neurodegenerative dementias in the Western Pacific region. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 50, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapko, D.; McCormack, R.; Black, C.; Staff, R.; Murray, A. Life-course determinants of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive aging and dementia—A systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Lussier-Therrien, M.; Biron, M.L.; Raymond, É.; Castonguay, J.; Naud, D.; Fortier, M.; Sévigny, A.; Houde, S.; Tremblay, L. Scoping study of definitions of social participation: Update and co-construction of an interdisciplinary consensual definition. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, X.; Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S.; Li, K. Social participation classification and activities in association with health outcomes among older adults: Results from a scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 81, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, K.; Kurumatani, N.; Hosoi, H. Social Participation and Cognitive Decline Among Community-dwelling Older Adults: A Community-based Longitudinal Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.; Rodrigues, P.; Voss, G.; Martinez-Pecino, R.; Delerue-Matos, A. Association between formal social participation and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults: A longitudinal study using SHARE data. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. Sect. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2024, 31, 932–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Chen, T.; Yu, N.X. The Longitudinal Dyadic Associations Between Social Participation and Cognitive Function in Older Chinese Couples. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, A.; Qi, Y.; Feng, W.; Hou, C.; Tao, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Associations between social and intellectual activities with cognitive trajectories in Chinese middle-aged and older adults: A nationally representative cohort study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wu, Y.; Mao, Z.; Liang, X. Association of Formal and Informal Social Support With Health-Related Quality of Life Among Chinese Rural Elders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellert, P.; Häusler, A.; Suhr, R.; Gholami, M.; Rapp, M.; Kuhlmey, A.; Nordheim, J. Testing the stress-buffering hypothesis of social support in couples coping with early-stage dementia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.M.; Carney, S.; Hannigan, C.; Brennan, S.; Wolfe, H.; Lynch, M.; Kee, F.; Lawlor, B. Systemic inflammatory markers and sources of social support among older adults in the Memory Research Unit cohort. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J. Sources of perceived social support and cognitive function among older adults: A longitudinal study in rural China. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1443689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Dong, X.; Katz, B.; Li, M. Source of perceived social support and cognitive change: An 8-year prospective cohort study. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 27, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Shin, J.I.; Sánchez, G.F.L.; Oh, H.; Kostev, K.; Jacob, L.; Law, C.T.; Carmichael, C.; Tully, M.A.; Koyanagi, A. Social participation and mild cognitive impairment in low- and middle-income countries. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Mishra, R. Impact of transition in work status and social participation on cognitive performance among elderly in India. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C. Beyond health care: Volunteer work, social participation, and late-life general cognitive status in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 229, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhu, C.W.; Neugroschl, J.; Aloysi, A.; Sano, M.; Li, C. Evaluating the Beijing Version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Identification of Cognitive Impairment in Monolingual Chinese American Older Adults. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2022, 35, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhang, S.; Yu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wan, Q. The Chinese Translation Study of the Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 948740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, C. Social engagement and physical frailty in later life: Does marital status matter? BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Yin, J.; Liang, P.; Zhang, H.; Kou, L.; Hao, M.; You, L.; Li, X.; et al. Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, Z.; Cook, C.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Y. Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Community-Based Centenarians. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 573530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Ramsch, C.; Uter, W.; Guigoz, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Thomas, D.R.; Anthony, P.; Charlton, K.E.; Maggio, M.; et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PROCESS Macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. PROCESS Macro for SPSS and SAS. Available online: https://processmacro.org/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Magnuson, K. Socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning: Moving from correlation to causation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2012, 3, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Bandinelli, S.; Ferrucci, L. Socioeconomic status during lifetime and cognitive impairment no-dementia in late life: The population-based aging in the Chianti Area (InCHIANTI) Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 24, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, D.; Whittle, S. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain—A systematic review of neuroimaging findings in youth. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 130, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, E.; Rodas De León, N.E.; Richardson, D.M. Childhood family socioeconomic status is linked to adult brain electrophysiology. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaraju, A.; Marzuki, A.A.; Chan, J.K.; Wong, K.Y.; Phon-Amnuaisuk, P.; Vafa, S.; Chew, J.; Chia, Y.C.; Jenkins, M. Structural and functional brain correlates of socioeconomic status across the life span: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 162, 105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.S.C.; Coecke, S. Associations between Socioeconomic Status, Cognition, and Brain Structure: Evaluating Potential Causal Pathways Through Mechanistic Models of Development. Cogn. Sci. 2023, 47, e13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, M.; Avlund, K.; Mortensen, E.L. Socio-economic position early in life, cognitive development and cognitive change from young adulthood to middle age. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövdén, M.; Fratiglioni, L.; Glymour, M.M.; Lindenberger, U.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Education and Cognitive Functioning Across the Life Span. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest A J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2020, 21, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, K.; MacDonald, L.A.; Crowe, M.; McClure, L.A.; Howard, V.J.; Wadley, V.G. The Role of Occupation in Explaining Cognitive Functioning in Later Life: Education and Occupational Complexity in a U.S. National Sample of Black and White Men and Women. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; A Walker, K.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Mars, N.; Vahtera, J.; Suominen, S.B.; Lallukka, T.; Rahkonen, O.; Pietiläinen, O.; et al. Cognitive stimulation in the workplace, plasma proteins, and risk of dementia: Three analyses of population cohort studies. BMJ 2021, 374, n1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boots, E.A.; Schultz, S.A.; Almeida, R.P.; Oh, J.M.; Koscik, R.L.; Dowling, M.N.; Gallagher, C.L.; Carlsson, C.M.; Rowley, H.A.; Bendlin, B.B.; et al. Occupational Complexity and Cognitive Reserve in a Middle-Aged Cohort at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2015, 30, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydström, A.; Darin-Mattsson, A.; Kåreholt, I.; Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. Occupational complexity and cognition in the FINGER multidomain intervention trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 2438–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, M.; Mohamadian, F.; Ghajarieah, M.; Direkvand-Moghadam, A. The Effect of Individual Factors, Socioeconomic and Social Participation on Individual Happiness: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, VC01–VC04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, C.; Konstantinidis, T. A Review of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status Change and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashida, T.; Kondo, N.; Kondo, K. Social participation and the onset of functional disability by socioeconomic status and activity type: The JAGES cohort study. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, D.; Chen, Y.; Tan, M.; Chen, X. Effect of socioeconomic status on the physical and mental health of the elderly: The mediating effect of social participation. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achdut, N.; Sarid, O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: The mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, D. The effect of activities of daily living on anxiety in older adult people: The mediating role of social participation. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1450826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, P.; Ma, X. Effects of tai chi, ba duan jin, and walking on the mental health status of urban older people living alone: The mediating role of social participation and the moderating role of the exercise environment. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1294019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 29, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, T.K. Neural mechanisms of the link between giving social support and health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1428, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Q.; Peng, C.; Guo, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yip, P.S.F. Mechanisms connecting objective and subjective poverty to mental health: Serial mediation roles of negative life events and social support. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, S.M.; Pai, M. Social Support From Family and Friends, Educational Attainment, and Cognitive Function. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 43, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifian, N.; Grühn, D. The Differential Impact of Social Participation and Social Support on Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2019, 88, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins-Jackson, P.B.; George, K.M.; Besser, L.M.; Hyun, J.; Lamar, M.; Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Bubu, O.M.; Flatt, J.D.; Heyn, P.C.; Cicero, E.C.; et al. The structural and social determinants of Alzheimer’s disease related dementias. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 3171–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, A.; Munford, L.; Sutton, M. Estimating the heterogeneous health and well-being returns to social participation. Health Econ. 2023, 32, 1921–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Variable Definition and Assignment |

|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |

| Cognitive function | MoCA scores. Value range: 0–30 scores |

| Independent variables | |

| Income | Retire pension monthly. 1 = less than 2000 CNY/month; 2 = 2000–6000 CNY/month; 3 = more than 6000 CNY/month |

| Education | Educational scores. 1 = less than 6 scores; 2 = 6–10 scores; 3 = more than 10 scores. |

| Occupation | Occupational complexity scores. 1 = less than 53 scores; 2 = 53–90 scores; 3 = more than 90 scores |

| Mediating variables | |

| Social participation | Scores. Value range:5–20 scores |

| Social support | Scores. Value range: 12–84 scores |

| Covariates | |

| Age | 1 = 60–65 years old; 2 = 66–75 years old; 3 = 71–75 years old; 4 = more than 75 years old |

| Sex | 1 = male; 2 = female |

| Marital status | 1 = married and living with a spouse; 2 = separated (widowed or divorced) |

| Sleep quality | PSQI scores: 1 = less than 5 scores; 2 = 5–10 scores; 3 = more than 10 scores |

| Smoking status | 1 = current smoking; 2 = never or quit smoking |

| Drinking status | 1 = current drink; 2 = never or occasional drinking |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1 = less than 24; 2 = more than or equal to 24 |

| Nutrition status | MNA scores: 1 = less than 12 scores; 2 = more than and equal to 12 |

| Co-morbidities | 1 = none; 2 = one chronic disease; 3 = more than two diseases |

| Categorical Measures | N (%) | MoCA (Scores) Mean (SD) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income (CNY/month) | <2000 | 205 (20.9%) | 18.06 ± 5.60 | |

| 2000~6000 | 695 (71.0%) | 20.31 ± 5.30 | ||

| >6000 | 79 (8.1%) | 22.40 ± 5.08 | <0.001 | |

| Occupation (scores) | <53 | 325 (33.2%) | 19.12 ± 5.86 | |

| 53~90 | 336 (34.2%) | 20.33 ± 5.29 | ||

| >90 | 318 (32.5%) | 20.57 ± 5.10 | 0.01 | |

| Education (scores) | <6 | 315 (32.2%) | 18.50 ± 6.03 | |

| 6~10 | 330 (33.7%) | 20.85 ± 4.61 | ||

| >10 | 331 (33.8%) | 20.56 ± 5.40 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 413 (42.4%) | 20.14 ± 5.40 | |

| Female | 564 (57.6%) | 19.91 ± 5.50 | 0.501 | |

| Age (years) | 60~65 | 288 (29.4%) | 21.33 ± 4.57 | |

| 66~70 | 336 (34.3%) | 20.48 ± 4.89 | ||

| 71~75 | 169 (17.3%) | 19.99 ± 5.61 | ||

| >75 | 185 (18.9%) | 17.07 ± 6.44 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <24 | 586 (59.9%) | 19.96 ± 5.40 | |

| ≥24 | 374 (38.2%) | 20.05 ± 5.58 | 0.794 | |

| Missing | 19 (1.9%) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 848 (86.6%) | 20.33 ± 5.27 | |

| Separated | 131 (13.4%) | 17.89 ± 6.13 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 177 (18.1%) | 20.67 ± 4.85 | |

| No or quit | 802 (81.9%) | 19.86 ± 5.58 | 0.050 | |

| Drinking | Yes | 154 (15.7%) | 20.90 ± 4.71 | |

| No or quit | 825 (84.3%) | 19.84 ± 5.57 | 0.014 | |

| Co-morbidities | None | 163 (16.6%) | 19.90 ± 5.80 | |

| 1 | 375 (38.3%) | 20.09 ± 5.43 | ||

| ≥2 | 242 (24.7%) | 19.39 ± 5.64 | 0.311 | |

| Missing | 199 (20.3%) | |||

| Nutrition status (MNA, scores) | ≤12 | 30 (6.1%) | 19.32 ± 5.67 | |

| >12 | 465 (93.9%) | 20.29 ± 5.35 | 0.011 | |

| Sleep quality (PSQI, scores) | <5 | 573 (58.5%) | 20.63 ± 5.26 | |

| 5~10 | 327 (33.4%) | 19.38 ± 5.57 | ||

| >10 | 79 (8.1%) | 18.12 ± 5.72 | <0.001 | |

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Cognitive Function (MoCA, Scores) | Social Participation (Scores) | Social Support (Scores) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive function (MoCA, scores) | 20.1 (5.46) | 1 | ||

| Social participation (scores) | 11.3 (4.1) | 0.350 *** | 1 | |

| Social support (scores) | 59.1 (14.8) | 0.139 *** | 0.169 *** | 1 |

| Mediation Variable | Independent Variables | Dependent Variable (Cognitive Function) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnibus Total Effect | Omnibus Direct Effect | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| Social participation | Income | 18.294 *** | 12.759 *** | 0.307~0.461 |

| Occupation | 8.487 *** | 4.088 ** | 0.313~0.471 | |

| Education | 11.120 *** | 7.481 *** | 0.316~0.472 | |

| Social support | Income | 18.294 *** | 16.301 *** | 0.005~0.053 |

| Occupation | 8.487 *** | 8.258 *** | 0.013~0.058 | |

| Education | 11.120 *** | 9.594 *** | 0.008~0.054 | |

| Mediation Variables | Socioeconomic Conditions | Cognitive Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ci | aib | Bootstrap 95% CI | |aib/ci| | ||

| Social participation | Income (ref: <2000 CNY/month) | ||||

| 2000~6000 | 1.949 *** | 0.358 | 0.110~0.614 | 18.36% | |

| >6000 | 3.799 *** | 0.777 | 0.349~1.222 | 20.45% | |

| Occupation(ref: <53 scores) | |||||

| 53~90 | 1.262 ** | 0.358 | 0.123~0.614 | 28.36% | |

| >90 | 1.574 ** | 0.561 | 0.299~0.851 | 35.64% | |

| Education (ref: <6 scores) | |||||

| 6~10 | 1.814 *** | 0.311 | 0.058~0.572 | 17.14% | |

| >10 | 1.511 *** | 0.562 | 0.294~0.853 | 39.19% | |

| Social support | Income (ref: <2000 CNY/month) | ||||

| 2000~6000 | 1.949 *** | 0.132 | 0.019~0.282 | 6.77% | |

| >6000 | 3.799 *** | 0.160 | 0.017~0.372 | 4.21% | |

| Occupation(ref: <53 scores) | |||||

| 53~90 | 1.262 ** | 0.011 | −0.073~0.103 | -- | |

| >90 | 1.574 ** | 0.034 | −0.042~0.132 | -- | |

| Education (ref: <6 scores) | |||||

| 6~10 | 1.814 *** | 0.096 | 0.013~0.214 | 5.29% | |

| >10 | 1.511 *** | 0.156 | 0.035~0.318 | 10.32% | |

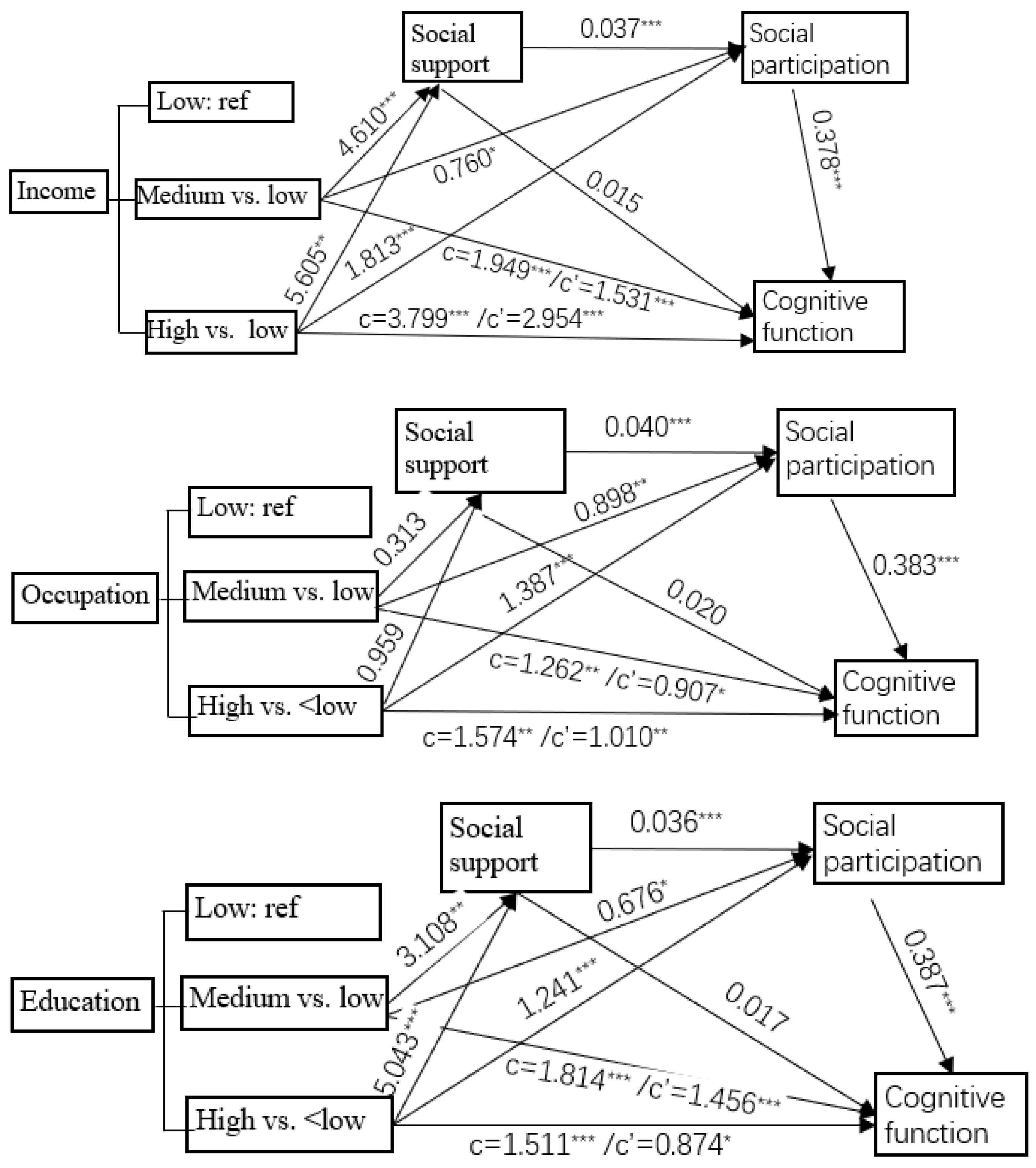

| Relative Direct Effects | β | S.E | t | P | 95% CI of β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Income (refer = low income level) | ||||||

| Medium income → social support | 4.610 | 1.144 | 4.029 | <0.001 | 2.365 | 6.855 |

| Medium income → social participation | 0.760 | 0.319 | 2.384 | 0.017 | 0.134 | 1.385 |

| Medium income → cognitive function | 1.531 | 0.394 | 3.887 | <0.001 | 0.758 | 2.303 |

| High income → social support | 5.605 | 1.937 | 2.894 | 0.004 | 1.805 | 9.406 |

| High income → social participation | 1.813 | 0.537 | 3.373 | 0.001 | 0.758 | 2.868 |

| High income → cognitive function | 2.954 | 0.666 | 4.437 | <0.001 | 1.647 | 4.261 |

| Social support → social participation | 0.037 | 0.009 | 4.175 | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.055 |

| Social support → cognitive function | 0.015 | 0.011 | 1.321 | 0.184 | −0.007 | 0.036 |

| Social participation → cognitive function | 0.378 | 0.04 | 9.535 | <0.001 | 0.300 | 0.455 |

| Occupation (refer = low level of occupation complexity) | ||||||

| Medium occupation → social support | 0.313 | 1.123 | 0.278 | 0.781 | −1.891 | 2.516 |

| Medium occupation → social participation | 0.898 | 0.307 | 2.928 | 0.003 | 0.296 | 1.499 |

| Medium occupation → cognitive function | 0.907 | 0.383 | 2.366 | 0.018 | 0.155 | 1.660 |

| High occupation → social support | 0.956 | 1.137 | 0.841 | 0.401 | −1.276 | 3.188 |

| High occupation → social participation | 1.387 | 0.311 | 4.465 | <0.001 | 0.777 | 1.997 |

| High occupation → cognitive function | 1.010 | 0.391 | 2.583 | 0.010 | 0.243 | 1.776 |

| Social support → social participation | 0.040 | 0.009 | 4.559 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.057 |

| Social support → cognitive function | 0.020 | 0.011 | 1.841 | 0.066 | −0.001 | 0.042 |

| Social participation → cognitive function | 0.383 | 0.040 | 9.562 | <0.001 | 0.304 | 0.461 |

| Education (refer = low educational level) | ||||||

| Medium education → social support | 3.108 | 1.138 | 2.732 | 0.006 | 0.875 | 5.341 |

| Medium education → social participation | 0.676 | 0.316 | 2.141 | 0.033 | 0.056 | 1.296 |

| Medium education → cognitive function | 1.456 | 0.392 | 3.713 | <0.001 | 0.687 | 2.226 |

| High education → social support | 5.043 | 1.138 | 4.431 | <0.001 | 2.810 | 7.276 |

| High education → social participation | 1.241 | 0.318 | 3.906 | <0.001 | 0.618 | 1.865 |

| High education → cognitive function | 0.874 | 0.397 | 2.203 | 0.028 | 0.096 | 1.653 |

| Social support → social participation | 0.036 | 0.009 | 4.044 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.053 |

| Social support → cognitive function | 0.017 | 0.011 | 1.529 | 0.127 | −0.005 | 0.039 |

| Social participation → cognitive function | 0.387 | 0.040 | 9.704 | <0.001 | 0.309 | 0.465 |

| Socioeconomic Conditions | Mediation Path | Cognitive Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ci | aib | Bootstrap 95% CI of aib | |aib/ci| | ||

| Income (ref: low-income level) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.949 *** | 0.067 | −0.032~0.193 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.949 *** | 0.287 | 0.042~0.539 | 14.7% | |

| Social support → social participation | 1.949 *** | 0.065 | 0.025~0.115 | 3.3% | |

| High level | Social support | 3.799 *** | 0.082 | −0.038~0.243 | --- |

| Social participation | 3.799 *** | 0.685 | 0.261~1.136 | 18.0% | |

| Social support → social participation | 3.799 *** | 0.078 | 0.023~0.152 | 2.0% | |

| Occupation (ref: low level of occupation complexity) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.262 ** | 0.006 | −0.047~0.070 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.262 ** | 0.344 | 0.117~0.591 | 27.3% | |

| Social support → social participation | 1.262 ** | 0.005 | −0.030~0.044 | --- | |

| High level | Social support | 1.574 ** | 0.019 | −0.028~0.090 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.574 ** | 0.531 | 0.277~0.824 | 33.7% | |

| Social support → social participation | 1.574 ** | 0.015 | −0.019~0.055 | --- | |

| Education (ref: low educational level) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.814 *** | 0.053 | −0.013~0.150 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.814 *** | 0.262 | 0.020~0.515 | 14.4% | |

| Social support → social participation | 1.814 *** | 0.043 | 0.010~0.089 | 2.4% | |

| High level | Social support | 1.511 *** | 0.086 | −0.022~0.223 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.511 *** | 0.480 | 0.224~0.761 | 31.8% | |

| Social support → social participation | 1.511 *** | 0.070 | 0.027~0.129 | 4.6% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Wang, T.; Guo, H.; Zheng, G. The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Cognitive Ability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mediating Effect of Social Participation and Social Support. Healthcare 2025, 13, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050551

Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Ye M, Wang T, Guo H, Zheng G. The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Cognitive Ability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mediating Effect of Social Participation and Social Support. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050551

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Yilin, Yu Zhang, Mingzhu Ye, Tingting Wang, Huining Guo, and Guohua Zheng. 2025. "The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Cognitive Ability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mediating Effect of Social Participation and Social Support" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050551

APA StyleZheng, Y., Zhang, Y., Ye, M., Wang, T., Guo, H., & Zheng, G. (2025). The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Cognitive Ability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mediating Effect of Social Participation and Social Support. Healthcare, 13(5), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050551