New Antidepressant Prescriptions Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Sex and Age Differences in a Population-Based Ecological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics Statement

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanne, J.H.; Hayasaki, E.; Zastrow, M.; Pulla, P.; Smith, P.; Rada, A.G. COVID-19: How doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ 2020, 368, m1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Belled, A.; Tejada-Gallardo, C.; Fatsini-Prats, M.; Alsinet, C. Mental health among the general population and healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of well-being and psychological distress prevalence. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 8435–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, R.T.; McManus, S.; O’Connor, R.C. Evidencing the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health across Europe. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 2, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lange, K.W. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and global mental health. Glob. Health J. Amst. Neth. 2021, 5, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiou, V.; Papadopoulou, A.; Pomini, V.; Yotsidi, V.; Kalemi, G.; Chatzimichail, K.; Michopoulos, I.; Kaparoudaki, A.; Papadopoulou, M.; Smyrnis, N.; et al. A one-year longitudinal study on suicidal ideation, depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 73, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jia, X.; Shi, H.; Niu, J.; Yin, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrela, M.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Ferreira, P.L.; Roque, F. The Use of Antidepressants, Anxiolytics, Sedatives and Hypnotics in Europe: Focusing on Mental Health Care in Portugal and Prescribing in Older Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, E8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.J.; Croker, R.; Curtis, H.J.; MacKenna, B.; Goldacre, B. Trends in antidepressant prescribing in England. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschtritt, M.E.; Slama, N.; Sterling, S.A.; Olfson, M.; Iturralde, E. Psychotropic medication prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicine 2021, 100, e27664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiger, M.; Castelpietra, G.; Wesselhoeft, R.; Lundberg, J.; Reutfors, J. Utilization of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tratamiento de la depresión en atención primaria: Cuándo y con qué. INFAC-Inf. Farmacoter. 2017, 25, 1–11.

- Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Data Protection-European Commission [Internet]. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-topic/data-protection_en (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Park, J. Mental health among women and girls of diverse backgrounds in Canada before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: An intersectional analysis. Health Rep. 2024, 35, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.L.N.; Martínez, P.F.; Bretón, E.F.; Martínez Alfonso, M.M.; Gil, P.S. Psychotropic consumption before and during COVID-19 in Asturias, Spain. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamer, A.; Saint-Dizier, C.; Levaillant, M.; Hamel-Broza, J.-F.; Ayed, E.; Chazard, E.; Bubrovszky, M.; D’Hondt, F.; Génin, M.; Horn, M. Prolonged increase in psychotropic drug use among young women following the COVID-19 pandemic: A French nationwide retrospective study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.B.; Misol, R.C.; Alonso, M.D.C.F.; Tizón, J.L. Pandemia de la COVID-19 y salud mental: Reflexiones iniciales desde la atención primaria de salud española. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Pauly, V.; Brousse, Y.; Llorca, P.-M.; Cortese, S.; Rahmati, M.; Correll, C.U.; Gosling, C.J.; Fornaro, M.; Solmi, M.; et al. Mental Health Care Utilization and Prescription Rates Among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults in France. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2452789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bandt, D.; Haile, S.R.; Devillers, L.; Bourrion, B.; Menges, D. Prescriptions of antidepressants and anxiolytics in France 2012-2022 and changes with the COVID-19 pandemic: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Ment. Health 2024, 27, e301026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicieza-Garcia, M.L.; Manso, G.; Salgueiro, E. Updated 2014 STOPP criteria to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling elderly patients. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 55, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancani, L.; Marinucci, M.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Forced Social Isolation and Mental Health: A Study on 1,006 Italians Under COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.-M.; Lee, S.M.; Hong, M.; Kim, S.-J.; Sohn, S.; Choi, Y.-K.; Hyun, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, S.H.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Job Loss Impacts on Mental Health in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtahedi, D.; Dagnall, N.; Denovan, A.; Clough, P.; Hull, S.; Canning, D.; Lilley, C.; Papageorgiou, K.A. The Relationship Between Mental Toughness, Job Loss, and Mental Health Issues During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 607246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newnham, E.A.; Mergelsberg, E.L.P.; Chen, Y.; Kim, Y.; Gibbs, L.; Dzidic, P.L.; Ishida DaSilva, M.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Shimomura, K.; Narita, Z.; et al. Long term mental health trajectories after disasters and pandemics: A multilingual systematic review of prevalence, risk and protective factors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 97, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos, M.A.; Saiz, J.; Muñoz, M. Mental health consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. A longitudinal study of the alarm situation and return to the new normality. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 110219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Silva, A.N. da The Mental Health Impacts of a Pandemic: A Multiaxial Conceptual Model for COVID-19. Behav. Sci. Basel Switz. 2023, 13, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, B.; Lyne, J.; McNicholas, F. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Looking back and moving forward. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, P.; Chircop, D.; Azzopardi, A. To Hell and Back: A Performer’s mental health journey during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnaze, M.M.; Kious, B.M.; Feuerman, L.Z.; Classen, S.; Robinson, J.O.; Bloss, C.S.; McGuire, A.L. Public mental health during and after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Opportunities for intervention via emotional self-efficacy and resilience. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1016337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Motulsky, A.; Eguale, T.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Tamblyn, R. Treatment Indications for Antidepressants Prescribed in Primary Care in Quebec, Canada, 2006-2015. JAMA 2016, 315, 2230–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PRE (n = 131,300) | PAN (n = 129,260) | POST (n = 130,126) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| 0–20 | 23,495 | 17.89 | 23,016 | 17.80 | 23,070 | 17.73 |

| 21–40 | 28,527 | 21.73 | 26,832 | 20.76 | 26,744 | 20.55 |

| 41–60 | 42,510 | 32.38 | 42,239 | 32.68 | 42,540 | 32.69 |

| 61–80 | 27,761 | 21.14 | 28,316 | 21.91 | 28,981 | 22.27 |

| >80 | 9007 | 6.86 | 8857 | 6.85 | 8791 | 6.76 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 67,677 | 51.54 | 66,586 | 51.51 | 67,007 | 51.49 |

| Male | 63,623 | 48.46 | 62,674 | 48.49 | 63,119 | 48.51 |

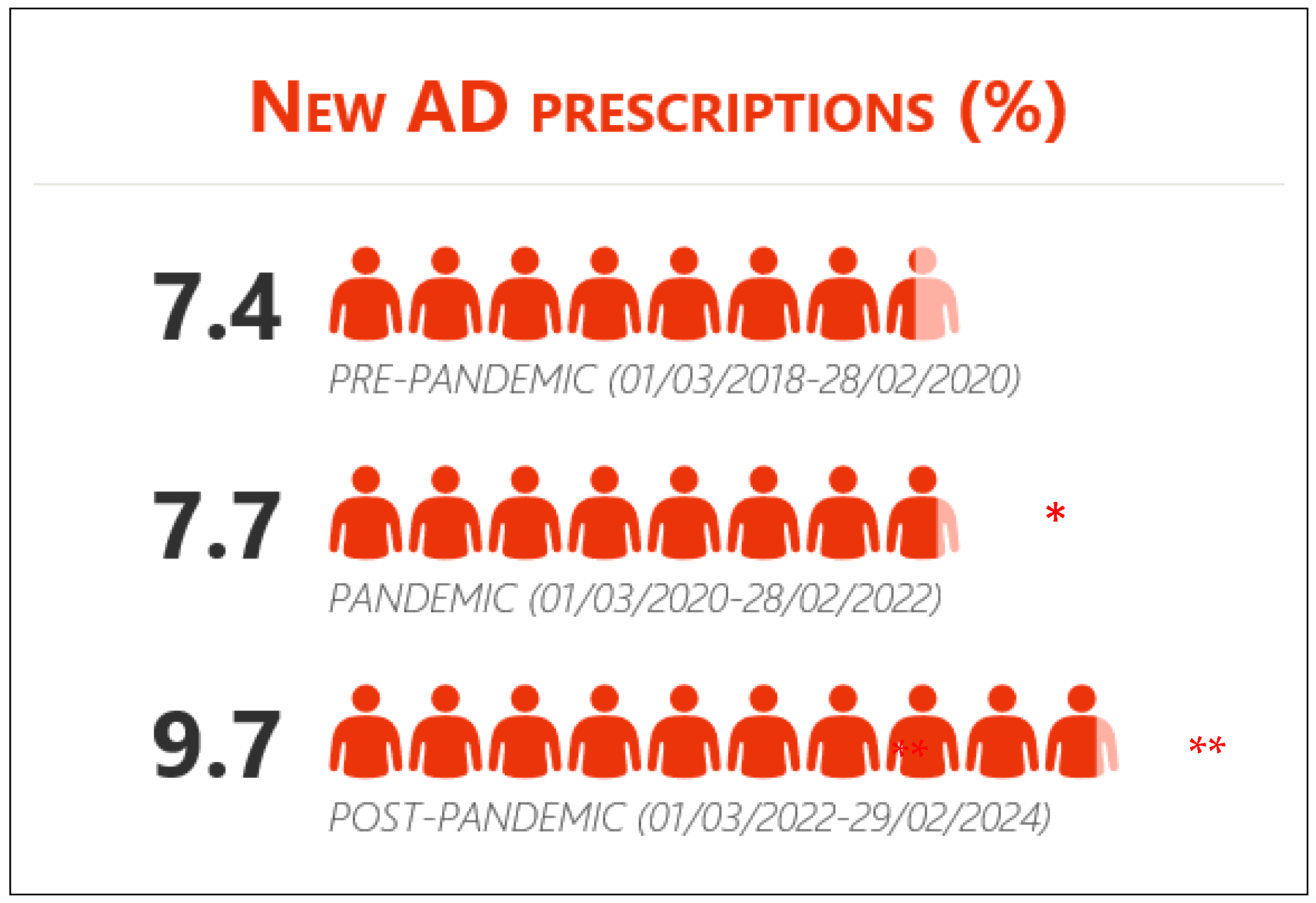

| PRE 1 March 2018–28 February 2020 | PAN 1 March 2020–28 February 2022 | POST 1 March 2022–29 February 2024 | PAN vs. PRE | POST vs. PAN | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | N | % | N | % | N | % | OR (95% CI) | Z | p | OR (95% CI) | Z | p |

| 0–20 | 259 | 1.1 | 321 | 1.4 | 374 | 1.6 | 1.27 (1.08–1.50) | 2.834 | 0.005 | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | 1.993 | 0.046 |

| 21–40 | 1653 | 5.8 | 1695 | 6.3 | 2130 | 8.0 | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 2.577 | 0.010 | 1.28 (1.20–1.37) | 7.389 | <0.001 |

| 41–60 | 3594 | 8.5 | 3610 | 8.5 | 4728 | 11.1 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 0.481 | 0.630 | 1.34 (1.28–1.40) | 12.520 | <0.001 |

| 61–80 | 2678 | 9.6 | 2741 | 9.7 | 3402 | 11.7 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 0.132 | 0.894 | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | 7.952 | <0.001 |

| >80 | 1543 | 17.1 | 1616 | 18.2 | 1943 | 22.1 | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) | 1.952 | 0.051 | 1.27 (1.18–1.37) | 6.376 | <0.001 |

| PAN vs. PRE | POST vs. PAN | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Sex | PRE (%) | PAN (%) | POST (%) | OR (95% CI) | Z | p | OR (95% CI) | Z | p |

| 0–20 | ♂ | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.15 (0.86–1.56) | 0.945 | 0.344 | 1.08 (0.82–1.44) | 0.565 | 0.572 |

| ♀ | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.33 (1.09–1.62) | 2.797 | 0.005 | 1.20 (1.00–1.43) | 1.996 | 0.045 | |

| 21–40 | ♂ | 4.1 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | 1.160 | 0.246 | 1.28 (1.14–1.43) | 4.343 | <0.001 |

| ♀ | 7.5 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 2.341 | 0.019 | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | 6.059 | 0.001 | |

| 41–60 | ♂ | 5.7 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 0.229 | 0.819 | 1.39 (1.28–1.50) | 8.354 | < 0.001 |

| ♀ | 11.3 | 11.4 | 14.5 | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.458 | 0.647 | 1.32 (1.24–1.39) | 9.426 | < 0.001 | |

| 61–80 | ♂ | 6.0 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 1.05 (0.94–1.16) | 0.871 | 0.384 | 1.27 (1.16–1.40) | 5.040 | < 0.001 |

| ♀ | 12.7 | 12.6 | 15.1 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.382 | 0.702 | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) | 6.315 | < 0.001 | |

| >80 | ♂ | 13.4 | 15.1 | 18.3 | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 1.942 | 0.054 | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) | 3.333 | < 0.001 |

| ♀ | 19.1 | 19.9 | 24.1 | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 1.077 | 0.282 | 1.28 (1.17–1.39) | 5.417 | < 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez-Cengotitabengoa, M.; Sanchez-Martinez, M.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Long-Martinez, D.; Dunford, D.; Revuelta, P.; Echevarria, E.; Calvo, B. New Antidepressant Prescriptions Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Sex and Age Differences in a Population-Based Ecological Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050502

Martinez-Cengotitabengoa M, Sanchez-Martinez M, Sanchez-Martinez A, Long-Martinez D, Dunford D, Revuelta P, Echevarria E, Calvo B. New Antidepressant Prescriptions Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Sex and Age Differences in a Population-Based Ecological Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050502

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Cengotitabengoa, Monica, Monike Sanchez-Martinez, Andoni Sanchez-Martinez, Daniel Long-Martinez, Daisy Dunford, Paula Revuelta, Enrique Echevarria, and Begoña Calvo. 2025. "New Antidepressant Prescriptions Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Sex and Age Differences in a Population-Based Ecological Study" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050502

APA StyleMartinez-Cengotitabengoa, M., Sanchez-Martinez, M., Sanchez-Martinez, A., Long-Martinez, D., Dunford, D., Revuelta, P., Echevarria, E., & Calvo, B. (2025). New Antidepressant Prescriptions Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Sex and Age Differences in a Population-Based Ecological Study. Healthcare, 13(5), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050502