Perception of Health and Its Predictors Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Duration, and Study Setting

2.2. Participant Selection and Sampling

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Sample Size

2.4. Study Questionnaire Development and Description

2.5. Study Questionnaire Validation and Reliability

2.6. Pilot Study and Justification for Hail City Selection

2.7. Data Collection

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Perception of Health Among Saudi Individuals

Differences in Health Perception Across Specific Demographic Groups

3.3. Sociodemographic Predictors of Good Health Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh

3.4. Behavioural Risk Factors and Co-Morbidities Associated with Perception of Good Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Practical Applications and Public Health Recommendations

7. Key Findings

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

References

- Chang, A.Y.; Skirbekk, V.F.; Tyrovolas, S.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Dieleman, J.L. Measuring population ageing: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e159–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lego, V.d. Health expectancy indicators: What do they measure? Cad. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 29, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Rao, S.R.; Ressalam, J.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Agaronnik, N.D.; Donelan, K.; Lagu, T.; Campbell, E.G. Physicians’ Perceptions Of People With Disability And Their Health Care: Study reports the results of a survey of physicians’ perceptions of people with disability. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislaghi, B.; Cislaghi, C. Self-rated health as a valid indicator for health-equity analyses: Evidence from the Italian health interview survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, S.R.; Aguiar, H.J.R. Self-Perception of Health Among the Elderly in the Northeast Region of Brazil: A Population-Based Study; Seven Editora: Sao Jose dos Pinhais, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Palenzuela-Luis, N.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.Á.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B. Questionnaires assessing adolescents’ Self-Concept, Self-Perception, physical activity and lifestyle: A systematic review. Children 2022, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević Jerković, O.; Sauliūnė, S.; Šumskas, L.; Birt, C.A.; Kersnik, J. Determinants of self-rated health in elderly populations in urban areas in Slovenia, Lithuania and UK: Findings of the EURO-URHIS 2 survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27 (Suppl. S2), 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela-Luis, N.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.Á.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B. International comparison of self-concept, self-perception and lifestyle in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.O.d.; Diniz, P.R.; Santos, M.E.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Farah, B.Q.; Tassitano, R.M.; Oliveira, L.M. Health self-perception and its association with physical activity and nutritional status in adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dramé, M.; Cantegrit, E.; Godaert, L. Self-rated health as a predictor of mortality in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.-M.; Yu, T.-F.; Liem, A.; Teh, P.-L.; Su, T.T. The association of self-perception of aging and quality of life in older adults: A systematic review. The Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorem, G.; Cook, S.; Leon, D.A.; Emaus, N.; Schirmer, H. Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: A cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šprocha, B.; Bleha, B. Mortality, health status and self-perception of health in Slovak Roma communities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 153, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyamini, Y. Health and illness perceptions. In The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, A.; Ramires, A.; Moura, A.d.; Souto, T.; Maroco, J. Psychological well-being and health perception: Predictors for past, present and future. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 46, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.W.; Mowbray, O.; Johnson, L. Examining the association between healthcare perceptions and behaviors that address social determinants of health. J. Public Health 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoob, M.; Paul, T.; Carbone, J.; Bokadia, H.; Cardy, R.E.; Kassam, S.; Anagnostou, E.; Andrade, B.F.; Penner, M.; Kushki, A. Predictors of health-related quality of life in neurodivergent children: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 27, 91–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Lakeh, M.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Tuffaha, M.; Daoud, F.; Al Saeedi, M.; Basulaiman, M.; Memish, Z.A.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Mokdad, A.H. Self-rated health among Saudi adults: Findings from a national survey, 2013. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Chaturvedi, N. Self-rated health in Pakistan: Results of a national health survey. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desesquelles, A.F.; Egidi, V.; Salvatore, M.A. Why do Italian people rate their health worse than French people do? An exploration of cross-country differentials of self-rated health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asfar, T.; Ahmad, B.; Rastam, S.; Mulloli, T.P.; Ward, K.D.; Maziak, W. Self-rated health and its determinants among adults in Syria: A model from the Middle East. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivičević Uhernik, A.; Skoko-Poljak, D.; Dečković-Vukres, V.; Jelavić, M.; Mihel, S.; Benjak, T.; Štefančić, V.; Draušnik, Ž.; Stevanović, R. Association of poor self-perceived health with demographic, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors in the Croatian adult population. Druš. istraž. čas. za opća druš. pitanja 2019, 28, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Lucchesi, L.R.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dingels, Z.V.; Fox, J.T.; Hamilton, E.B.; Henry, N.J.; Krohn, K.J.; Liu, Z. The global burden of falls: Global, regional and national estimates of morbidity and mortality from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Inj. Prev. 2020, 26 (Suppl. S2), i3–i11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaiodimos, L.; Kokkinidis, D.G.; Li, W.; Karamanis, D.; Ognibene, J.; Arora, S.; Southern, W.N.; Mantzoros, C.S. Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in-hospital outcomes, and higher in-hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism 2020, 108, 154262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, A.N.; Martins, M.R.O.; Peleteiro, B. Factors associated with self-perceived health status in Portugal: Results from the National Health Survey 2014. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 879432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, S.; Mannava, P.; Nagai, M.; Sobel, H.L. Reasons for discontinuation of contraception among women with a current unintended pregnancy in 36 low and middle-income countries. Contraception 2020, 101, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <50 years | 4848 | 34.0 |

| 50 to 75 years | 6945 | 48.8 |

| At least 75 years | 2446 | 17.2 |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 572 | 4.0 |

| Up to High School | 3937 | 27.6 |

| College/University | 7336 | 51.5 |

| Others | 2394 | 16.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 8062 | 56.6 |

| Male | 6177 | 43.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | 4939 | 34.7 |

| Married | 9300 | 65.3 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 7317 | 51.4 |

| Unemployed | 6922 | 48.6 |

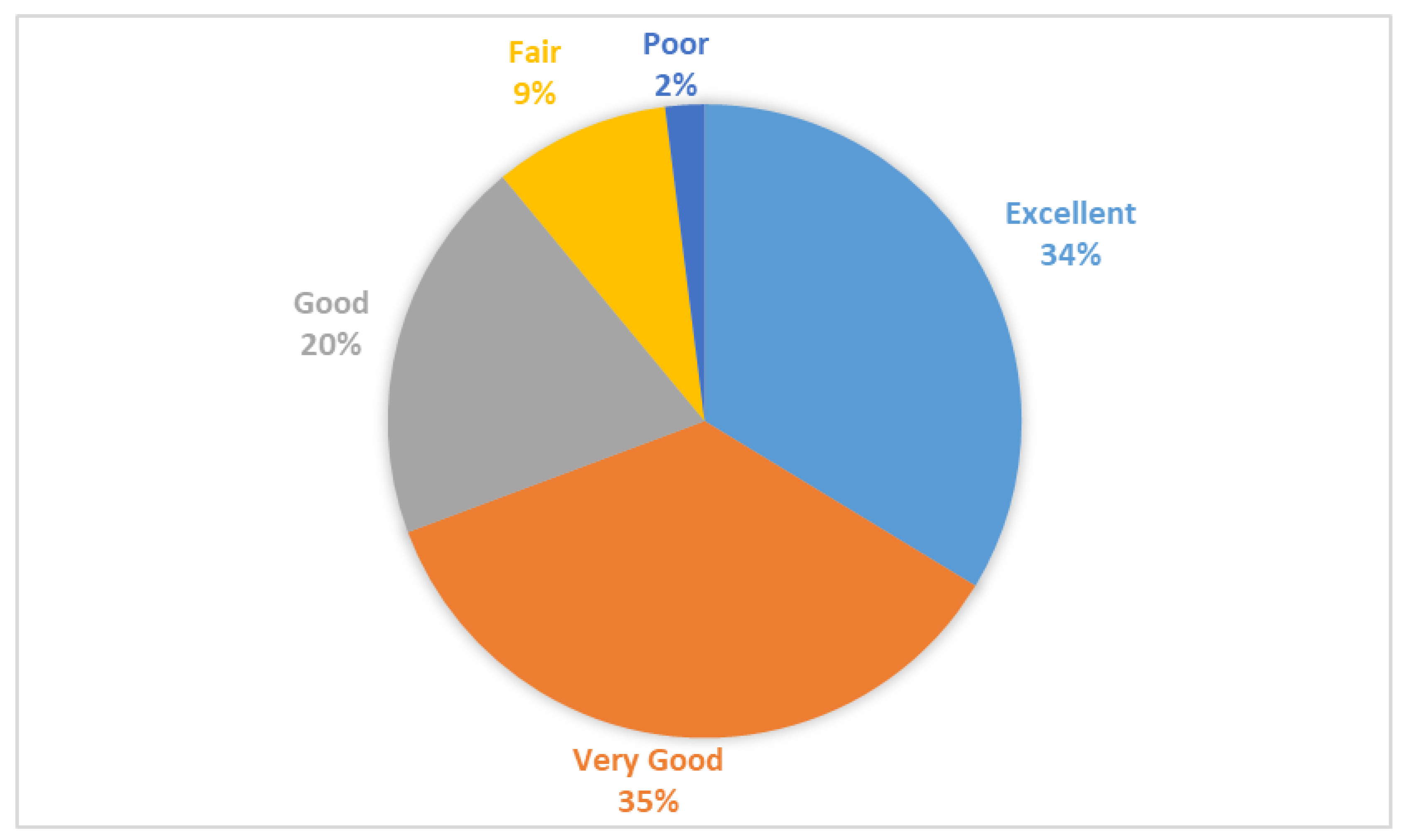

| Health status | ||

| Excellent | 4798 | 33.7 |

| Very good | 5076 | 35.6 |

| Good | 2815 | 19.8 |

| Fair | 1256 | 8.8 |

| Poor | 294 | 2.1 |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Yes | 3457 | 24.3 |

| No | 10,782 | 75.7 |

| Smoking | ||

| No | 10,297 | 72.3 |

| Yes | 3942 | 27.7 |

| Physical activity | ||

| No | 5598 | 39.3 |

| Yes | 8641 | 60.7 |

| Obesity | ||

| No | 13,502 | 94.8 |

| Yes | 737 | 5.2 |

| Variable | Health Perception Based on Current Health Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | |

| Age | <50 years | 1915 (39.9%) | 1610 (31.7%) | 851 (30.2%) | 367 (29.2%) | 105 (35.7%) |

| 50 to 75 years | 2312 (48.2%) | 2481 (48.9%) | 1408 (50.0%) | 611 (48.6%) | 133 (45.2%) | |

| At least 75 years | 571 (11.9%) | 985 (19.4%) | 556 (19.8%) | 278 (22.1%) | 56 (19.0%) | |

| Gender | Female | 2441 (50.9%) | 2875 (56.6%) | 1743 (61.9%) | 826 (65.8%) | 177 (60.2%) |

| Male | 2357 (49.1%) | 2201 (43.4%) | 1072 (38.1%) | 430 (34.2%) | 117 (39.8%) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 2735 (57.0%) | 3427 (67.5%) | 2019 (71.7%) | 909 (72.4%) | 210 (71.4%) |

| Single | 2063 (43.0%) | 1649 (32.5%) | 796 (28.3%) | 347 (27.6%) | 84 (28.6%) | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 2564 (53.4%) | 2519 (49.6%) | 1469 (52.2%) | 640 (51.0%) | 125 (42.5%) |

| Unemployed | 2234 (46.6%) | 2557 (50.4%) | 1346 (47.8%) | 616 (49.0%) | 169 (57.5%) | |

| Education | Primary | 145 (3.0%) | 180 (3.5%) | 145 (5.2%) | 76 (6.1%) | 26 (8.8%) |

| Up to High School | 1427 (29.7%) | 1289 (25.4%) | 858 (30.5%) | 294 (23.4%) | 69 (23.5%) | |

| College/University | 2547 (53.1%) | 2561 (50.5%) | 1354 (48.1%) | 696 (55.4%) | 178 (60.5%) | |

| Others | 679 (14.2%) | 1046 (20.6%) | 458 (16.3%) | 190 (15.1%) | 21 (7.1%) | |

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| <50 years | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 | ||||

| 50 to 75 years | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.07 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.97 | ||

| At least 75 years | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.32 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.18 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary | 1 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.119 | ||||

| Up to High School | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.38 | 1.15 | 0.95 | 1.39 | ||

| College/University | 1.03 | 0.85 | 1.24 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 1.28 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 1 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.027 | ||||

| Male | 1.10 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.18 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 1 | 0.375 | NA | |||||

| Married | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.11 | |||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed | 1 | 0.643 | NA | |||||

| Unemployed | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.09 | |||||

| Insurance coverage | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.652 | NA | |||||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.07 | |||||

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| Smoking | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.29 | ||||

| Physical activity | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.88 | |||||||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.08 | ||||

| Fast food consumption | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.174 | 1 | 0.109 | NA | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.15 | |||||||

| Obesity | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.031 | |||||||

| Yes | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.98 | ||||

| Diabetes | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.639 | NA | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.08 | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.225 | 1 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.523 | |||||||

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.2 | ||||

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.901 | |||||||

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.15 | ||||

| Heart disease | |||||||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Yes | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.76 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nasser, S.M.; Shubair, M.M.; Alharthy, A.; Al-Khateeb, B.F.; Howaimel, N.B.; AlJumah, M.; Angawi, K.; Alnaim, L.; Alwatban, N.; Farahat, A.F.; et al. Perception of Health and Its Predictors Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050464

Nasser SM, Shubair MM, Alharthy A, Al-Khateeb BF, Howaimel NB, AlJumah M, Angawi K, Alnaim L, Alwatban N, Farahat AF, et al. Perception of Health and Its Predictors Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050464

Chicago/Turabian StyleNasser, Seema Mohammed, Mamdouh M. Shubair, Amani Alharthy, Badr F. Al-Khateeb, Nouf Bin Howaimel, Mohammed AlJumah, Khadijah Angawi, Lubna Alnaim, Noof Alwatban, Abdulrahman Fayssal Farahat, and et al. 2025. "Perception of Health and Its Predictors Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050464

APA StyleNasser, S. M., Shubair, M. M., Alharthy, A., Al-Khateeb, B. F., Howaimel, N. B., AlJumah, M., Angawi, K., Alnaim, L., Alwatban, N., Farahat, A. F., & El-Metwally, A. (2025). Perception of Health and Its Predictors Among Saudis at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare, 13(5), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050464