Enhancing High Reliability in Oncology Care: The Critical Role of Nurses—A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

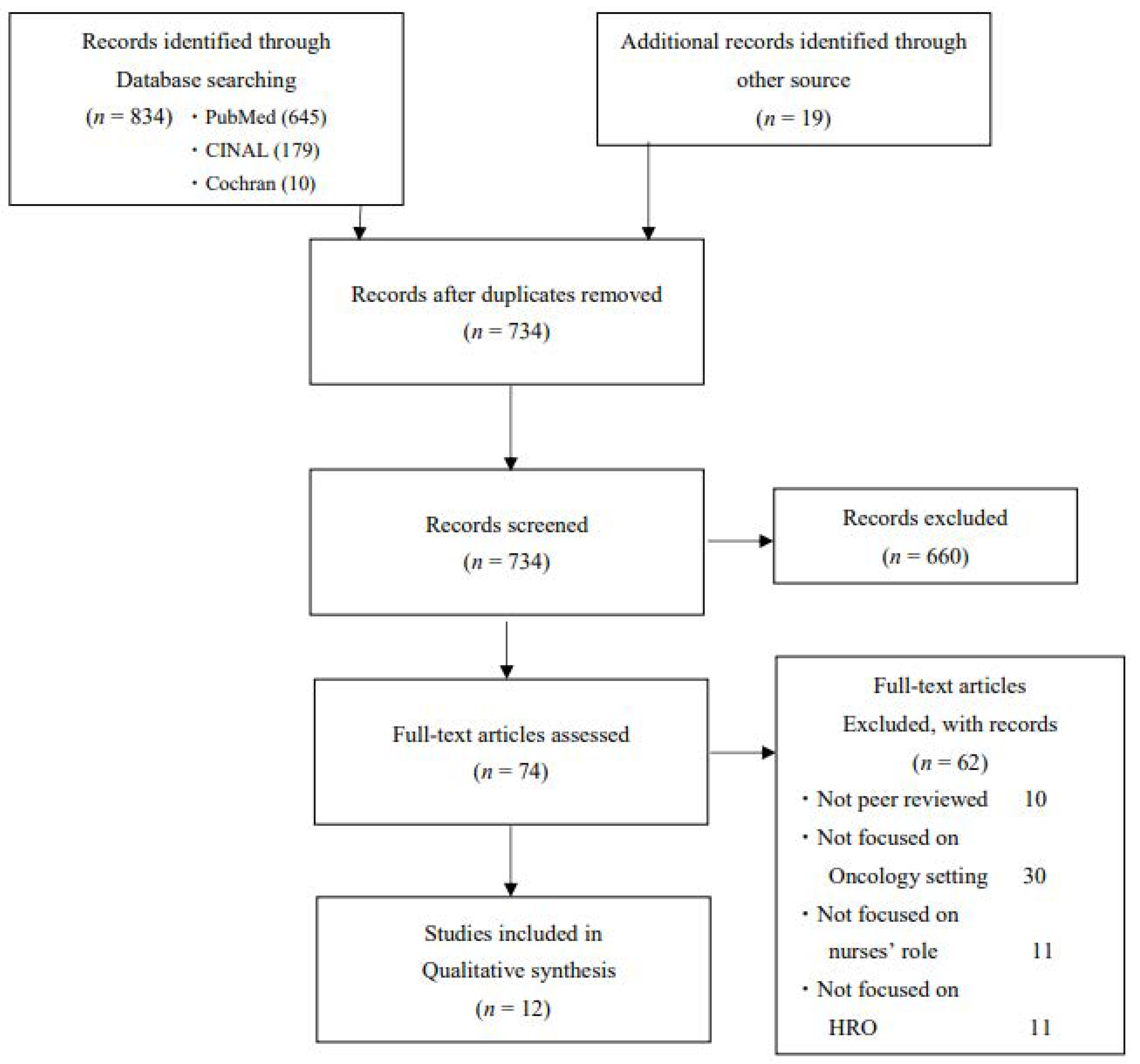

2. Methods

2.1. Approach

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Themes of Included Studies

3.4. Establishing of Standardized and Safe Administration

3.4.1. Enforcement of Rules and Multiple Safety Checks

3.4.2. Evidence-Based

3.4.3. Promoting the Quality Improvement Process

3.5. Enhancing Situational Awareness

3.5.1. Proactive Identification of Patient Conditions

3.5.2. Improved Situational Awareness Through Standardized Structure

3.5.3. Increasing Empowerment to Proactively Escalate Their Concerns

3.6. Promoting Effective Communication

3.6.1. Openness in Communication

3.6.2. Accurate and Structured Communication

3.7. Advocating Patient

3.7.1. Express a Large Variety of Barriers to Speak up Concerns

3.7.2. Trade-Off

3.7.3. Establish a Shared Mental Relationship

3.8. Building a Safety Culture

3.8.1. Make a Priority for Safety

3.8.2. Trust

3.8.3. Establish and Reinforce a “Culture of Voice”

3.8.4. Promote Collective Commitment

3.9. Leadership in Improving a Culture of Safety

3.9.1. Maintain the Direction of the Change

3.9.2. Create Education and Encourage for Staff

3.9.3. Audit and Maintain a Culture of Safety

3.9.4. Servant Leadership

3.10. Staff Engagement

3.10.1. Education and Coaching

3.10.2. Encourage Staff to Be Involved

3.11. Patient Engagement

Promoting Communication Between Patients and the Team

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti, M.; Khan, K.; Keers, R.N.; Abuzour, A.S.; Phipps, D.; Kontopantelis, E.; Bower, P.; Campbell, S.; Haneef, R.; Avery, A.J.; et al. Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 366, l4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Burden of Preventable Medication-Related Harm in Health Care: A Systematic Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Medication Without Harm: Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Womer, R.B.; Tracy, E.; Soo-Hoo, W.; Bickert, B.; DiTaranto, S.; Barnsteiner, J.H. Multidisciplinary Systems Approach to Chemotherapy Safety: Rebuilding Processes and Holding the Gains. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 4705–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapalan, S.; Lang, D. Health Care Organizations as Complex Adaptive Systems. Health Care Manag. 2020, 39, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bany Hamdan, A.; Javison, S.; Alharbi, M. Healthcare Professionals’ Culture Toward Reporting Errors in the Oncology Setting. Cureus 2023, 15, e38279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, S.L.; Cavanaugh, S.; Patino, F.; Swanson, J.W.; Abraham, C.; Clevenger, C.; Fisher, E. Improving Incident Reporting in a Hospital-Based Radiation Oncology Department: The Impact of a Customized Crew Resource Training and Event Reporting Intervention. Cureus 2021, 13, e14298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorin, S.S.; Haggstrom, D.; Han, P.K.J.; Fairfield, K.M.; Krebs, P.; Clauser, S.B. Ann Behav Cancer Care Coordination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 30 Years of Empirical Studies. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, E.C.; Narayan, G. Improving breast cancer care coordination and symptom management by using AI driven predictive toolkits. Breast 2020, 50, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.G.; Sutcliffe, K.M. High reliability organising in healthcare: Still a long way left to go. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2022, 31, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, K.D.; Volz, E.; Maity, A.; Gabriel, P.E.; Solberg, T.D.; Bergendahl, H.W.; Hahn, S.M. Journey Toward High Reliability: A Comprehensive Safety Program to Improve Quality of Care and Safety Culture in a Large, Multisite Radiation Oncology Department. J. Oncol. Practice 2016, 12, e603–e612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030: Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, S.; Luna, K.; Lofthus, J.; Marquardt, M.; Stelmokas, D. Becoming a High Reliability Organization: Operational Advice for Hospital Leaders (Prepared by the Lewin Group under Contract No. 290-04-0011); AHRQ Publication No. 08-0022; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Veazie, S.; Peterson, K.; Bourne, D. Evidence Brief: Implementation of High Reliability Organization Principles; Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; VA ESP Project #09-199. [Google Scholar]

- Veazie, S.; Peterson, K.; Bourne, D.; Anderson, J.; Damschroder, L.; Gunnar, W. Implementing High-Reliability Organization Principles Into Practice: A Rapid Evidence Review. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e320–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Spall, H.; Kassam, A.; Tollefson, T.T. Near-misses are an opportunity to improve patient safety: Adapting strategies of high reliability organizations to healthcare. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 23, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looper, K.; Winchester, K.; Robinson, D.; Price, A.; Langley, R.; Martin, G.; Jones, S.; Holloway, J.; Rosenberg, S.; Flake, S. Best Practices for Chemotherapy Administration in Pediatric Oncology: Quality and Safety Process Improvements (2015). J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 33, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, B.; Villamin, C.; Gallardo, L.D. Integration of Lean Visual Management Tools Into Quality Improvement Practices in the Hospital Setting. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2021, 37, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Shekelle, P.G.; Liu, J.L.; Sherwood Danz, M.; Foy, R.; Lim, Y.W.; Motala, A.; Rubenstein, L.V. Development of the Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set (QI-MQCS): A tool for critical appraisal of quality improvement intervention publications. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version Registration of Copyright. 2018, p. 1148552. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Green, A.; Roberson, A.; Webb, T.; Edwards, C. Implementing a Watcher Program to Improve Timeliness of Recognition of Deterioration in Hospitalized Children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 61, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plouff, C.; Byler, C.; Hyatt, M.; Jreissaty, C.; Joe, T.; Thomas, A.; Mejicanos, J.; Smith, R.; Hellstern, B.R.; Hassid, V.J. SAFE™ Initiative: A Step Closer to Positive Safety Culture and Improved Patient Experience. Cureus 2022, 14, e28554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, B. Adaptation of a Lean Tool Across Surgical Units to Improve Patient Experience. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2022, 37, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, D.N.; Looper, K.; Malone, R.A.; Ricken, B.; Slater, A.; Fuller, A.; McCaughey, M.; Niesen, A.; Smith, J.R.; Brozanski, B. Eliminating Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections in Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Quality Improvement Effort. Pediatr. Qual. Saf. 2023, 8, e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Duggar, W.N.; Packianathan, S.; Morris, B.; Yang, C.C. Chasing Zero Harm in Radiation Oncology: Using Pre-treatment Peer Review. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lichtner, V.; Franklin, B.D.; Dalla-Pozza, L.; Westbrook, J.I. Electronic ordering and the management of treatment interdependencies: A qualitative study of paediatric chemotherapy. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.L.; Gehring, K. Trade-offs between voice and silence: A qualitative exploration of oncology staff’s decisions to speak up about safety concerns. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, L.; Rannus, K.; Olofsson, A.; Kelly, D.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; EONS RECaN Group. Patient safety culture among European cancer nurses-An exploratory, cross-sectional survey comparing data from Estonia, Germany, Netherlands, and United Kingdom. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3535–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meisenberg, B.R.; Wright, R.R.; Brady-Copertino, C.J. Reduction in chemotherapy order errors with computerized physician order entry. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, e5–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingart, S.N.; Zhang, L.; Sweeney, M.; Hassett, M. Chemotherapy medication errors. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e191–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Hum. Factors 1995, 37, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P.; Hooper-Kyriakidis, P.; Stannard, D. Clinical Wisdom and Interventions in Critical Care: A Thinking in Action Approach; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, C.C.; Regenbogen, S.E.; Studdert, D.M.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Rogers, S.O.; Zinner, M.J.; Gawande, A.A. Patterns of Communication Breakdowns Resulting in Injury to Surgical Patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2007, 204, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltman, L.L. Disruptive behavior in obstetrics: A hidden threat to patient safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 587.e1–587.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.R.; James, D.C.; Knox, G.E. Nurse-Physician Communication During Labor and Birth: Implications for Patient Safety. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyndon, A.; Kennedy, H.P. Perinatal Safety: From Concept to Nursing Practice. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2010, 24, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.R.; Lyndon, A. Clinical disagreements during labor and birth: How does real life compare to best practice? MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2009, 34, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, A.H. Autonomy and advocacy in perinatal nursing practice. Nurs. Ethics 2008, 15, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettker, C.M.; Thung, S.F.; Norwitz, E.R.; Buhimschi, C.S.; Raab, C.A.; Copel, J.A.; Kuczynski, E.; Lockwood, C.J.; Funai, E.F. Impact of a comprehensive patient safety strategy on obstetric adverse events. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 200, 492.e1–492.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leap, L.L. Making Healthcare Safe: The Story of the Patient Safety Movement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cartland, J.; Green, M.; Kamm, D.; Halfer, D.; Brisk, M.A.; Wheeler, D. Trust relations in high-reliability organizations. BMJ Open Qual. 2022, 11, e001757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassin, M.R.; Loeb, J.M. High-reliability health care: Getting there from here. Milbank Q. 2013, 91, 459–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, A.; Haraden, C.; Federico, F.; Lenoci-Edwards, J. A Framework for Safe, Reliable and Effective Care; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.ihi.org/resources/white-papers/framework-safe-reliable-and-effective-care#downloads (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 9th ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto, A.M. Engaging All Employees in Efforts to Achieve High Reliability. Front. Health Serv. Manag. 2017, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.S.; Kelly, S.; Hanover, C. Promoting Psychological Safety in Healthcare Organizations. Mil. Med. 2022, 187, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, C.; Martin, P.; Tamblyn, R.; Benedetti, A.; Ahmed, S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: The EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.E.; Jacklin, R.; Sevdalis, N.; Vincent, C.A. Patient involvement in patient safety: What factors influence patient participation and engagement? Health Expect. 2007, 10, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Patients for Patient Safety—Partner Ships for Safer Health Care; World Health Organization WHO: Geneva, Switherland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Expert Consultation on the WHO Framework on Patient and Family Engagement; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switherland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jordan, S.; Kangasniemi, M. Patient participation in patient safety and nursing input—A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 24, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.; Hochreutener, M.; Wernli, M. Oncology nurses’ perceptions about involving patients in the prevention of chemotherapy adminis tration errors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, E84–E91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.E.; Sevdalis, N.; Neale, G.; Massey, R.; Vincent, C.A. Hospital patients’ reports of medical errors and undesirable events in their health care. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2013, 5, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarcher, M.; Rihari-Thomas, J.; Duffield, C.; Tuqiri, K.; Hackett, K.; Ferguson, C. Advanced practice nurses’ experiences of patient safety: A focus group study, Contemporary. Nurse 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Study Population and Setting | Objective(s) | Design | Methods | Themes of Nurses’ Role * | QI-MQCS Score,% | MMAT Score,% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evans et al. (2021) [29] | The Medical Emergency Team involved nurses; physicians, including residents, hospitalists, and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit representatives; and the pediatric inpatient acute care setting (i.e., medical–surgical, hematology-oncology, and intermediate care units), Arkansas Children’s Hospital, USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To describe implementation of a program to improve recognition and response to clinical deterioration within the pediatric inpatient acute care setting. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| B | 94 | - |

| Lichtner et al. (2020) [34] | Healthcare professionals, doctors (n = 10), nurses (n = 6), a pharmacist, and oncology CPOE team members (n = 2) in the oncology unit of a 350-bed tertiary pediatric hospital in New South Wales, Australia. | To investigate how computerized provider order entry (CPOE) for chemotherapy relates to other safety strategies in a pediatric clinical oncology unit, with a focus on the management of interdependencies. | Multi-method qualitative study |

| A, B | - | 100 |

| Looper et al. (2016) [23] | A multidisciplinary task force: physicians, advanced practice nurses, nursing leadership, staff nurses, pharmacy, nurse educators, and clinical research associates, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, USA Number of nurses; not noted. | To develop best practices for multidisciplinary teams managing chemotherapy for children and evaluate the process of their implementation. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| A, E | 81 | - |

| Plouff et al. (2022) [30] | The leadership team included physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and business and administrative leaders at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Sugar Land, Houston, USA Number of nurses; not noted. | To review the Secure, Attentive, Focused, Engaged (SAFETM) initiative to create, foster, and continuously improve safety culture and its impact on our safety culture and patient experience. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| A, C, E, F, G, H | 88 | - |

| Salinas et al. (2022) [24] | Hospital staff (nurses, nurse manager and clinical nurse leader) within the surgical cohort, Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To evaluate the effect of K-Card rounding on key quality measures such as patient experience and NSI, as well as to standardize workflows related to leadership rounding and process auditing. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| A, C, F, H | 81 | - |

| Salinas et al. (2022) [31] | Hospital staff (nurses, nurse manager, clinical nurse leader and associate directors) within the surgical cohort, Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To increase the percentile rank for responsiveness of hospital staff within the surgical cohort to 80%. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| F, G | 88 | - |

| Schwappach et al. (2014) [35] | Doctors (senior doctor, 4, resident, 10) and nurses (head nurse, 3, nurse, 15) at the ambulatory oncology units or on the wards, who had sufficient working experience in oncology, of six hospitals with seven oncology departments, Switzerland. | To explore factors that affect oncology staff’s decision to voice safety concerns or to remain silent and to describe the trade-offs they make. | Qualitative interview study |

| D, F | - | 100 |

| Sharp et al. (2019) [36] | Eligible participants were 393 cancer nurses from the four countries (Estonia, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) involved. Data collection was conducted anonymously on a voluntary basis during annual conferences of the National Cancer Nursing Societies in each country. | To explore the differences in perceived patient safety cultures among cancer nurses working in four European countries. | An exploratory cross-sectional study |

| C, E | - | 100 |

| Swanson et al. (2021) [11] | The department in this study was one of five national oncology hospital-based radiation oncology (RO) departments. The department staff comprised radiation oncology physicians, medical physicists, radiation therapists, nurses, and support personnel and were based in the USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To describe the development, implementation, and impact of a six-month, two-pronged team training and incident-learning intervention adapted from crew resource management (CRM) principles on the rate of incident reporting in a complex radiation oncology setting. | Quasi-experimental study |

| A, C, E | - | 100 |

| Vijayakumar S et.al. (2019) [33] | A multidisciplinary group’s consensus peer-review members included physicians, therapists, physicists, dosimetrists, and nurses working at the Radiation Oncology Department, University of MS Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To achieve the goal of “chase zero”, the authors conducted a pre-treatment and multidisciplinary group consensus peer-review (GCPR) program in radiation oncology to identify its effectiveness. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| E | 69 | - |

| Willis et al. (2023) [32] | A multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurse practitioners, nursing and physician leadership, frontline staff, and improvement specialists in a large free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital, St. Louis, USA. Number of nurses; not noted. | To describe the quality improvement initiative to eliminate Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSIs) in the pediatric oncology population at our institution. | Implementation study quality improvement project. |

| A, B, D, E, F | 88 | - |

| Woodhouse et al. (2016) [17] | The Department of Radiation Oncology at the University of Pennsylvania, USA, including approximately 39 physicians, 43 medical physicists, 30 dosimetrists, 28 nurses, and 82 radiation therapists, | To describe advancing a large, multisite radiation oncology department toward high reliability through the implementation of a comprehensive safety culture (SC) program. | Implementation study quality improvement project |

| B | 94 | - |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| A. Establishing standardized and safe administration | A-1. Enforcement of rules and multiple safety checks [23,24,34] |

| A-2. Evidence-based [11,23,30,32] | |

| A-3. Promoting the quality improvement process [23,24,32] | |

| B. Enhancing situational awareness | B-1. Proactive identification of patient conditions [29] |

| B-2. Improved situational awareness through standardized structure [17,34] | |

| B-3. Increasing empowerment to proactively escalate their concerns [29,32] | |

| C. Promoting effective communication | C-1. Openness in communication [36] |

| C-2. Accurate and structured communication [11,24,30] | |

| D. Advocacy of patient | D-1. Expresses a large variety of barriers to address concerns [35] |

| D-2. Trade-off [35] | |

| D-3. Establish a shared mental relationship [32] | |

| E. Building safety culture | E-1. Make a priority for safety [23] |

| E-2. Trust [30] | |

| E-3. Establish and reinforce a “culture of voice” [11,32,33,36] | |

| E-4. Promote collective commitment [32,33] | |

| F. Leadership in improving culture of safety | F-1. Maintain the direction of the change [24,30] |

| F-2. Create education and encourage for staff [24,31,35] | |

| F-3. Audit and maintain a culture of safety [32] | |

| F-4. Servant leadership [31,35] | |

| G. Staff engagement | G-1. Education and coaching [31] |

| G-2. Encourage staff to be involved [30,31] | |

| H. Patient engagement | H-1. Promoting communication between patients and the team [24,30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komatsu, H.; Hara, A.; Koyama, F.; Komatsu, Y. Enhancing High Reliability in Oncology Care: The Critical Role of Nurses—A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030283

Komatsu H, Hara A, Koyama F, Komatsu Y. Enhancing High Reliability in Oncology Care: The Critical Role of Nurses—A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(3):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030283

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomatsu, Hiroko, Akemi Hara, Fumiko Koyama, and Yasuhiro Komatsu. 2025. "Enhancing High Reliability in Oncology Care: The Critical Role of Nurses—A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 3: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030283

APA StyleKomatsu, H., Hara, A., Koyama, F., & Komatsu, Y. (2025). Enhancing High Reliability in Oncology Care: The Critical Role of Nurses—A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis. Healthcare, 13(3), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030283