Association Between Income and Well-Being Among Working Women in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Questionnaire

2.2. Statistical Analysis

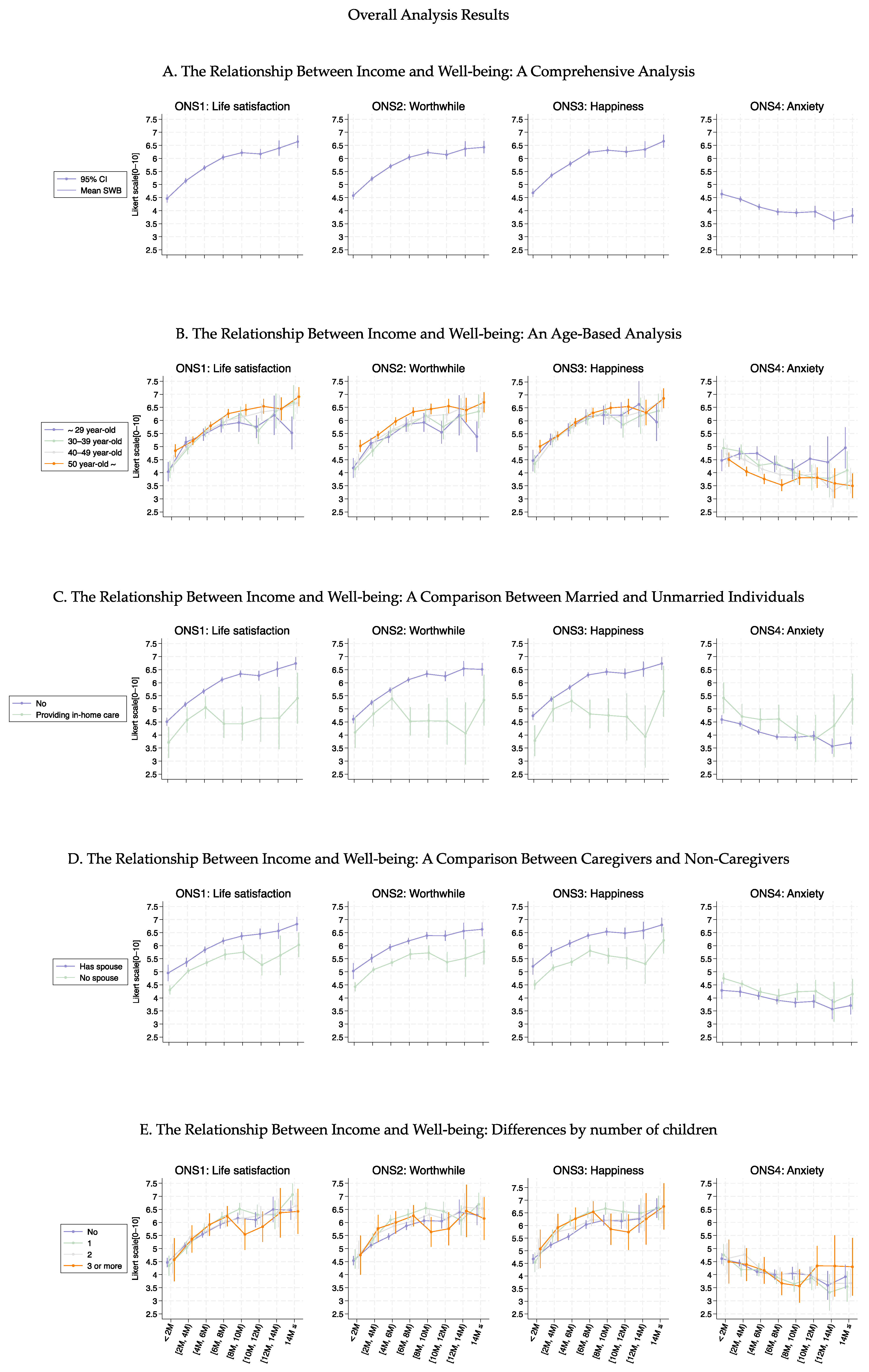

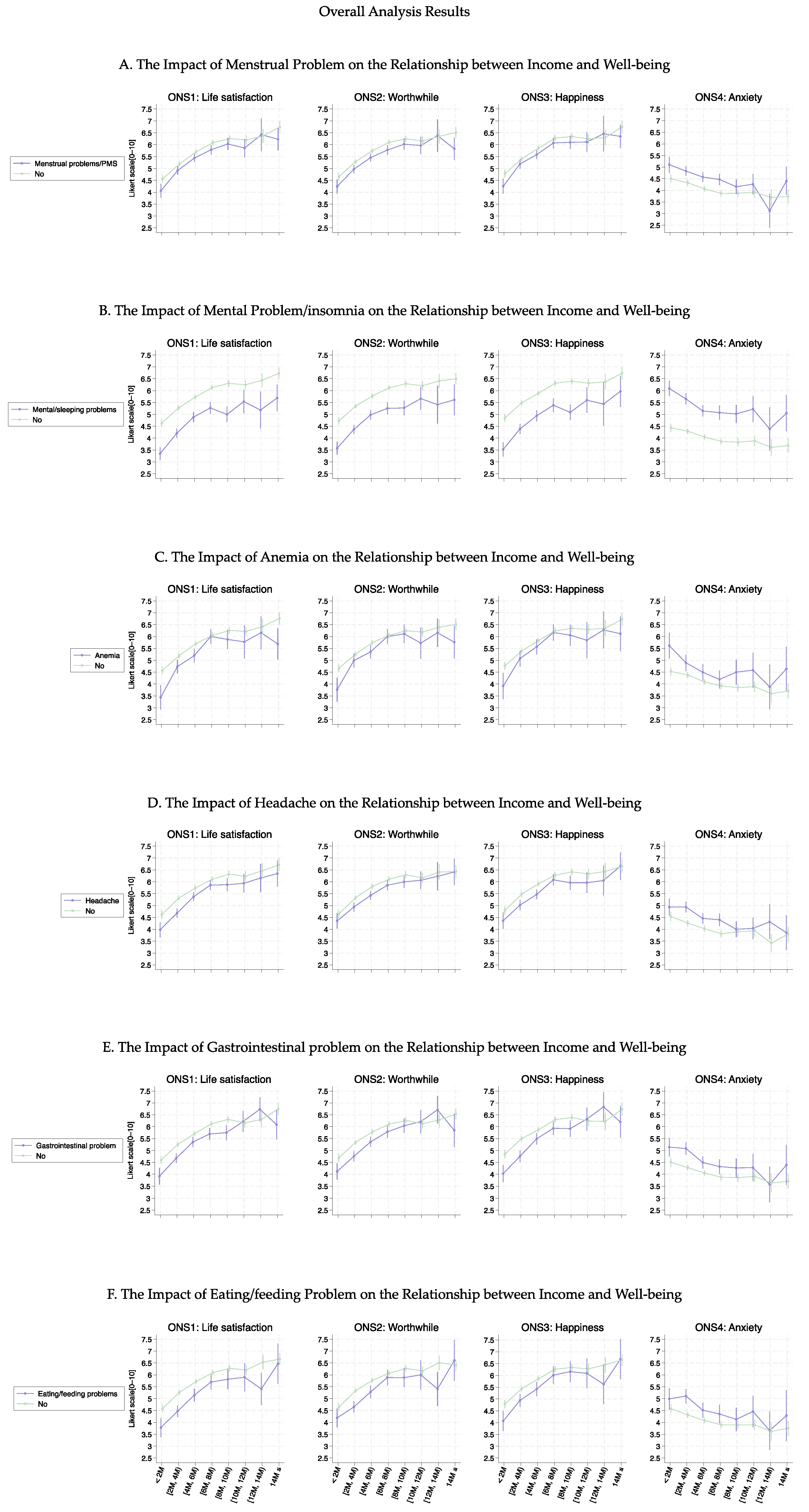

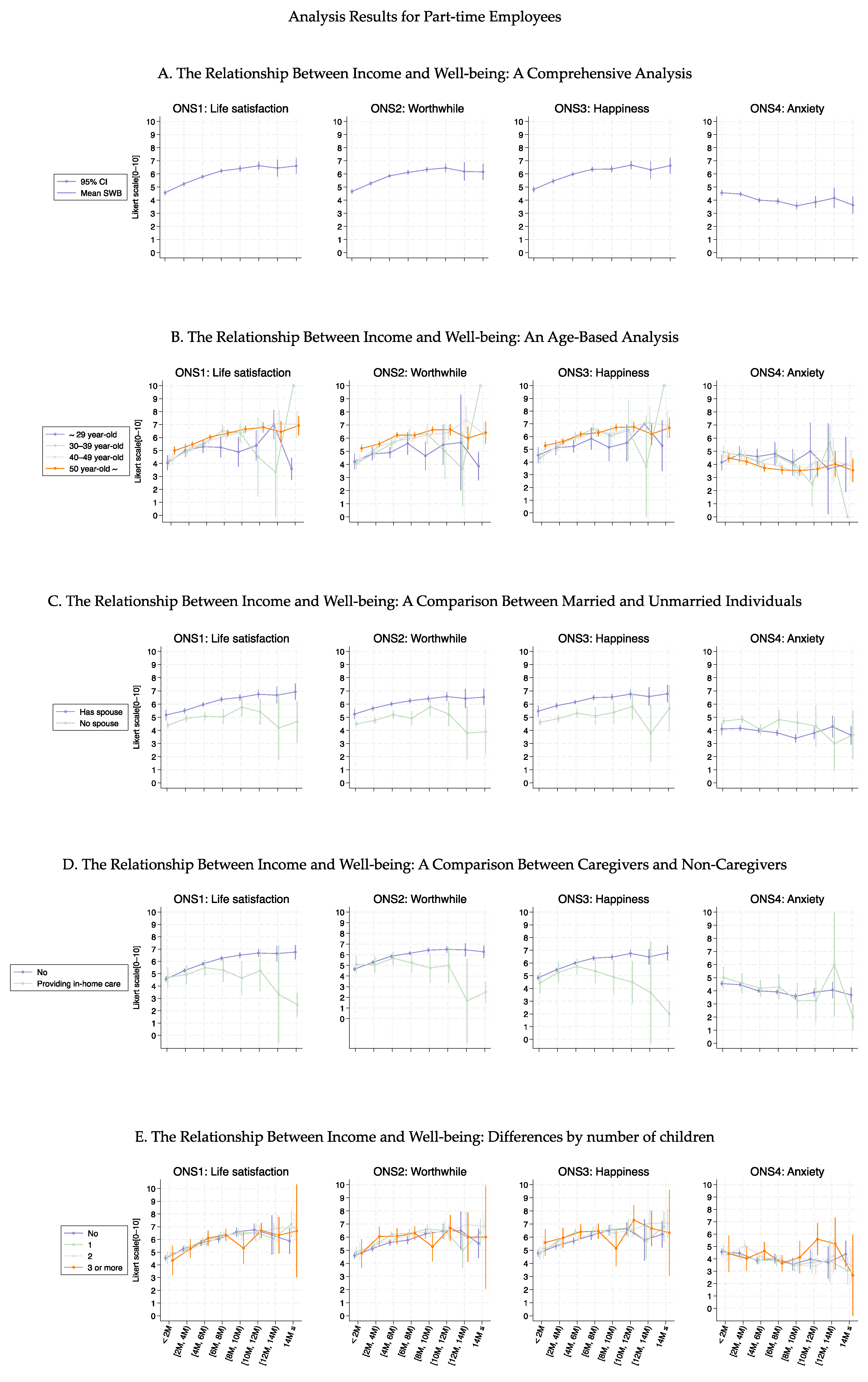

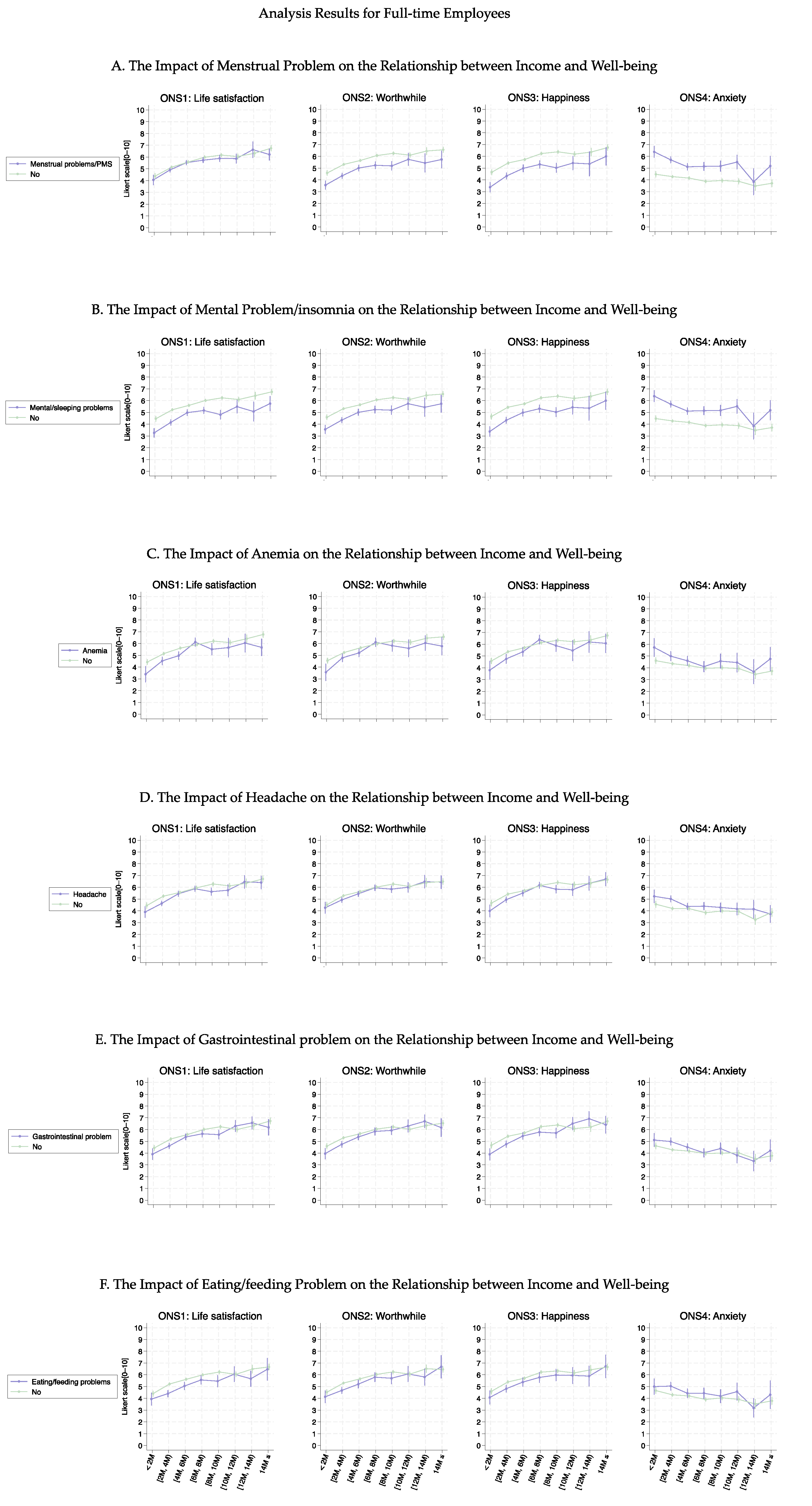

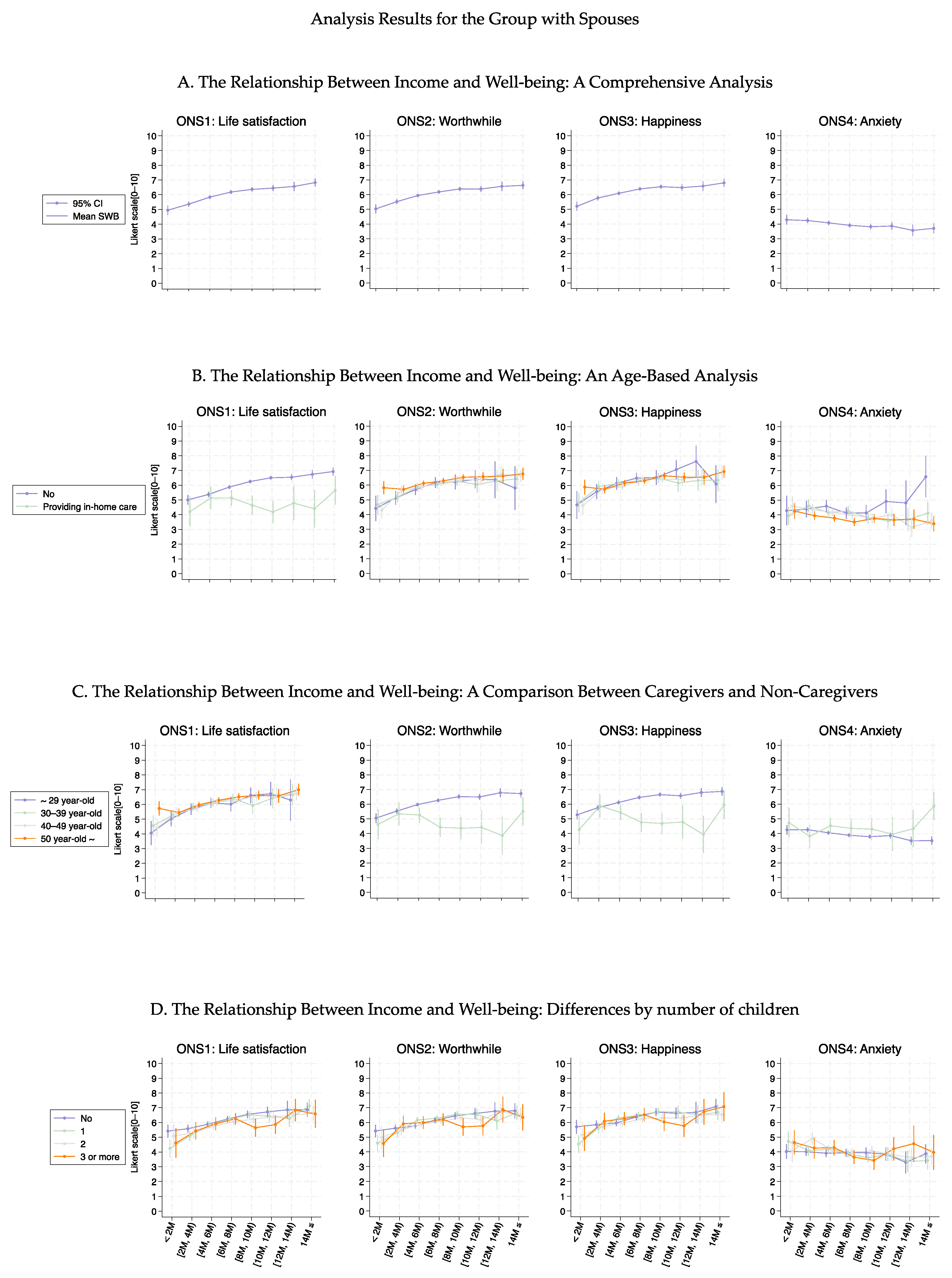

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Killingsworth, M.A. Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016976118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Managi, S. Income raises human well-being indefinitely, but age consistently slashes it. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoundi, Z. Moving Beyond GDP: A Pathway to Wellbeing and Sustainability. SDG KNOWLEDGE HUB. Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/moving-beyond-gdp-a-pathway-to-wellbeing-and-sustainability/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Duraiappah, A.; Hamid, Z.A. The Growing Disconnect Between GDP and Wellbeing. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2014/05/growing-disconnect-gdp-wellbeing/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Vik, M.H.; Carlquist, E. Measuring subjective well-being for policy purposes: The example of well-being indicators in the WHO ‘Health 2020’ framework. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlin, R.A.; O’connor, K.J. The Easterlin Paradox. 2020. Available online: www.iza.org (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Kahneman, D.; Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16489–16493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Chan, M.Y. Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-Being Contributes to Health and Longevity. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2011, 3, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.J.; Proto, E.; Sgroi, D. Happiness and Productivity. J. Labor. Econ. 2015, 33, 789–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, C.S.; De Neve, J.-E.; Ward, G. Does Employee Happiness Have an Impact on Productivity? Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 1656–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.; De Neve, J.-E. World Happiness Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2021/ (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- World Happiness Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://happiness-report.s3.amazonaws.com/2024/WHR+24.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Gender Wage Gap. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/gender-wage-gap.html (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Oishi, S.; Kesebir, S.; Diener, E. Income Inequality and Happiness. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, R.E.; Lachowsky, M. Menopause and sexuality: Prevalence of symptoms and impact on quality of life. Maturitas 2009, 63, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurihara, R. Patriarchy in the Empire of Japan, A Contemporary History of Gender in Japan. J. Adm. Soc. Sci. Fukushima Univ. 2009, 22, 65–160. Available online: https://ir.lib.fukushima-u.ac.jp/repo/repository/fukuro/R000004055/2-405.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Masuda, M. Possibilities of a New Japanese-Style Welfare Society Concept. Tokyo. October 2024. Available online: https://ippjapan.org/pdf/Opinion301_MMasuda.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Cabinet Office. Public Opinion Survey on Gender-Equal Society. Public Opinion Survey. Available online: https://survey.gov-online.go.jp/r04/r04-danjo/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Sasayama, K.; Nishimura, E.; Yamaji, N.; Ota, E.; Tachimori, H.; Igarashi, A.; Arata, N.; Yoneoka, D.; Saito, E. Current Use and Discrepancies in the Adoption of Health-Related Internet of Things and Apps Among Working Women in Japan: Large-Scale, Internet-Based, Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e51537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS). Personal Well-Being User Guidance. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/methodologies/personalwellbeingsurveyuserguide (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Altonji, J.G.; Elder, T.E.; Taber, C.R. Selection on Observed and Unobserved Variables: Assessing the Effectiveness of Catholic Schools. J. Political Econ. 2005, 113, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.; Merkley, K.J.; Silva, F.B.G. Government Guarantees and Banks’ Earnings Management. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2023, 63, 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2022 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions. Tokyo. July 2023. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa22/dl/05.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Kazuma, S. Children and Happiness—Does Having Children Increase Happiness? Panel Data Research Center at Keio University Discussion Paper. April 2021. Available online: https://www.pdrc.keio.ac.jp/uploads/DP2021-002_jp.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The 7th National Survey on Family Trends Report, 2022. Tokyo, April 2024. Available online: https://www.ipss.go.jp/ps-katei/j/NSFJ7/Mhoukoku/kateidoukou7_kekka_20240426.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. “令和3年度子供の学習費調査の結果を公表します (The Results of the Fiscal Year 2021 Survey on Children’s Educational Expenses Have Been Released). Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20221220-mxt_chousa01-000026656_1a.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Okada, T. Mental Health of Caregivers and Psychological/Emotional Development of their Children. Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica 2021, 123, 740–745. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Bränn, E.; Bertone-Johnson, E.; Sjölander, A.; Fang, F.; Oberg, A.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Lu, D. The bidirectional association between premenstrual disorders and perinatal depression: A nationwide register-based study from Sweden. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 働く女性と生理休暇について(About Working Women and Menstrual Leave). Tokyo. September 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11909000/001150877.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Güzeldere, H.K.B.; Efendioğlu, E.H.; Mutlu, S.; Esen, H.N.; Karaca, G.N.; Çağırdar, B. The relationship between dietary habits and menstruation problems in women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safiri, S.; Kolahi, A.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.; Karamzad, N.; Bragazzi, N.; Sullman, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Collins, G.; Kaufman, J.; et al. Burden of anemia and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, M.; Molero, P.; Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño, F.; Van der Does, W.; Angel Martínez-González, M. Diet quality and depression risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2023 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions. Tokyo. July 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa23/dl/03.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

| Household Annual Income | ||||||||||

| <2 M | 2–4 M | 4–6 M | 6–8 M | 8–10 M | 10–12 M | 12–14 M | 14 M> | Total | p-value | |

| N (%) | 1103 (11.03) | 2430 (24.30) | 2356 (23.56) | 1741 (17.41) | 1159 (11.59) | 586 (5.86) | 247 (2.47) | 378 (3.78) | 10,000 | |

| Age group (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 20s | 163 (14.78) | 518 (21.32) | 397 (16.85) | 297 (17.06) | 184 (15.88) | 88 (15.02) | 25 (10.12) | 42 (11.11) | 1714 (17.14) | |

| 30s | 223 (20.22) | 443 (18.23) | 509 (21.60) | 370 (21.25) | 243 (20.97) | 116 (19.80) | 55 (22.27) | 55 (14.55) | 2014 (20.14) | |

| 40s | 257 (23.30) | 582 (23.95) | 640 (27.16) | 483 (27.74) | 331 (28.56) | 180 (30.72) | 79 (31.98) | 124 (32.80) | 2676 (26.76) | |

| 50s | 355 (32.18) | 694 (28.56) | 621 (26.36) | 485 (27.86) | 343 (29.59) | 177 (30.20) | 73 (29.55) | 129 (34.13) | 2877 (28.77) | |

| 60s and above | 105 (9.52) | 193 (7.94) | 189 (8.02) | 106 (6.09) | 58 (5.00) | 25 (4.27) | 15 (6.07) | 28 (7.41) | 719 (7.19) | |

| Occupation (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Full-time job | 487 (44.15) | 1576 (64.86) | 1379 (58.53) | 1134 (65.13) | 829 (71.53) | 461 (78.67) | 194 (78.54) | 315 (83.33) | 6375 (63.75) | |

| Part-time job | 616 (55.85) | 854 (35.14) | 977 (41.47) | 607 (34.87) | 330 (28.47) | 125 (21.33) | 53 (21.46) | 63 (16.67) | 3625 (36.25) | |

| Final academic background (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Junior high graduate | 46 (4.17) | 45 (1.85) | 35 (1.49) | 13 (0.75) | 6 (0.52) | 3 (0.51) | 1 (0.40) | 1 (0.26) | 150 (1.50) | |

| Senior high graduate | 431 (39.08) | 851 (35.02) | 620 (26.32) | 431 (24.76) | 213 (18.38) | 91 (15.53) | 32 (12.96) | 39 (10.32) | 2708 (27.08) | |

| College graduate | 159 (14.42) | 371 (15.27) | 411 (17.44) | 277 (15.91) | 179 (15.44) | 90 (15.36) | 35 (14.17) | 49 (12.96) | 1571 (15.71) | |

| Vocational school | 194 (17.59) | 463 (19.05) | 420 (17.83) | 312 (17.92) | 197 (17.00) | 70 (11.95) | 28 (11.34) | 22 (5.82) | 1706 (17.06) | |

| University undergraduate | 255 (23.12) | 670 (27.57) | 818 (34.72) | 666 (38.25) | 527 (45.47) | 299 (51.02) | 127 (51.42) | 212 (56.08) | 3574 (35.74) | |

| Graduate school | 18 (1.63) | 30 (1.23) | 52 (2.21) | 42 (2.41) | 37 (3.19) | 33 (5.63) | 24 (9.72) | 55 (14.55) | 291 (2.91) | |

| Spouse (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 273 (24.75) | 792 (32.59) | 1394 (59.17) | 1269 (72.89) | 879 (75.84) | 448 (76.45) | 201 (81.38) | 290 (76.72) | 5546 (55.46) | |

| No | 830 (75.25) | 1638 (67.41) | 962 (40.83) | 472 (27.11) | 280 (24.16) | 138 (23.55) | 46 (18.62) | 88 (23.28) | 4454 (44.54) | |

| Number of children (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 795 (72.08) | 1741 (71.65) | 1309 (55.56) | 816 (46.87) | 484 (41.76) | 241 (41.13) | 86 (34.82) | 166 (43.92) | 5638 (56.38) | |

| 1 | 179 (16.23) | 389 (16.01) | 516 (21.90) | 452 (25.96) | 323 (27.87) | 156 (26.62) | 65 (26.32) | 86 (22.75) | 2166 (21.66) | |

| 2 | 89 (8.07) | 221 (9.09) | 405 (17.19) | 364 (20.91) | 269 (23.21) | 139 (23.72) | 69 (27.94) | 93 (24.60) | 1649 (16.49) | |

| 3 | 35 (3.17) | 62 (2.55) | 107 (4.54) | 99 (5.69) | 64 (5.52) | 44 (7.51) | 21 (8.50) | 25 (6.61) | 457 (4.57) | |

| 4 | 4 (0.36) | 13 (0.53) | 17 (0.72) | 10 (0.57) | 12 (1.04) | 5 (0.85) | 4 (1.62) | 2 (0.53) | 67 (0.67) | |

| 5≤ | 1 (0.09) | 4 (0.16) | 2 (0.08) | 0 (0.00) | 7 (0.60) | 1 (0.17) | 2 (0.81) | 6 (1.59) | 23 (0.23) | |

| Number of cohabitants who require care (%) | 0.070 | |||||||||

| 0 | 1043 (94.56) | 2324 (95.64) | 2241 (95.12) | 1664 (95.58) | 1087 (93.79) | 550 (93.86) | 230 (93.12) | 351 (92.86) | 9490 (94.90) | |

| 1 | 51 (4.62) | 99 (4.07) | 108 (4.58) | 70 (4.02) | 64 (5.52) | 31 (5.29) | 14 (5.67) | 23 (6.08) | 460 (4.60) | |

| 2≤ | 9 (0.82) | 7 (0.29) | 7 (0.30) | 7 (0.40) | 8 (0.69) | 5 (0.85) | 3 (1.21) | 4 (1.06) | 50 (0.50) | |

| Menstrual problems (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 827 (74.98) | 1690 (69.55) | 1648 (69.95) | 1233 (70.82) | 851 (73.43) | 443 (75.60) | 197 (79.76) | 289 (76.46) | 7178 (71.78) | |

| Yes | 276 (25.02) | 740 (30.45) | 708 (30.05) | 508 (29.18) | 308 (26.57) | 143 (24.40) | 50 (20.24) | 89 (23.54) | 2822 (28.22) | |

| Mental health problems/insomnia (%) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| No | 805 (72.98) | 1832 (75.39) | 1845 (78.31) | 1411 (81.05) | 959 (82.74) | 482 (82.25) | 208 (84.21) | 316 (83.60) | 7858 (78.58) | |

| Yes | 298 (27.02) | 598 (24.61) | 511 (21.69) | 330 (18.95) | 200 (17.26) | 104 (17.75) | 39 (15.79) | 62 (16.40) | 2142 (21.42) | |

| Anemia (%) | 0.633 | |||||||||

| No | 996 (90.30) | 2162 (88.97) | 2086 (88.54) | 1532 (88.00) | 1035 (89.30) | 528 (90.10) | 222 (89.88) | 336 (88.89) | 8897 (88.97) | |

| Yes | 107 (9.70) | 268 (11.03) | 270 (11.46) | 209 (12.00) | 124 (10.70) | 58 (9.90) | 25 (10.12) | 42 (11.11) | 1103 (11.03) | |

| Headaches (%) | 0.006 | |||||||||

| No | 834 (75.61) | 1800 (74.07) | 1735 (73.64) | 1313 (75.42) | 900 (77.65) | 459 (78.33) | 190 (76.92) | 308 (81.48) | 7539 (75.39) | |

| Yes | 269 (24.39) | 630 (25.93) | 621 (26.36) | 428 (24.58) | 259 (22.35) | 127 (21.67) | 57 (23.08) | 70 (18.52) | 2461 (24.61) | |

| Gastrointestinal problems (%) | 0.007 | |||||||||

| No | 885 (80.24) | 1955 (80.45) | 1898 (80.56) | 1419 (81.5) | 975 (84.12) | 503 (85.84) | 198 (80.16) | 319 (84.39) | 8152 (81.52) | |

| Yes | 218 (19.76) | 475 (19.55) | 458 (19.44) | 322 (18.5) | 184 (15.88) | 83 (14.16) | 49 (19.84) | 59 (15.61) | 1848 (18.48) | |

| Eating/feeding problems (%) | 0.036 | |||||||||

| No | 946 (85.77) | 2061 (84.81) | 2038 (86.5) | 1523 (87.48) | 1019 (87.92) | 516 (88.05) | 215 (87.04) | 340 (89.95) | 8658 (86.58) | |

| Yes | 157 (14.23) | 369 (15.19) | 318 (13.50) | 218 (12.52) | 140 (12.08) | 70 (11.95) | 32 (12.96) | 38 (10.05) | 1342 (13.42) | |

| ONS1: Life Satisfaction | ONS2: Worthwile | ONS3: Happiness | ONS4: Anxiety | ||||||

| Coefficients (95% CIs) | p-value | Coefficients (95% CIs) | p-value | Coefficients (95% CIs) | p-value | Coefficients (95% CIs) | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 4.97 (4.57, 5.37) | 0.000 | 4.53 (4.14, 4.92) | 0.000 | 4.70 (4.26, 5.13) | 0.000 | 4.10 (3.59, 4.61) | 0.000 | |

| Income | 0.22 (0.13, 0.31) | 0.000 | 0.23 (0.15, 0.32) | 0.000 | 0.27 (0.17, 0.37) | 0.000 | −0.02 (−0.14, 0.09) | 0.686 | |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 20s | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| 30s | −0.35 (−0.71, 0.00) | 0.053 | −0.41 (−0.76, −0.06) | 0.021 | −0.18 (−0.57, 0.21) | 0.362 | 0.39 (−0.07, 0.85) | 0.094 | |

| 40s | −0.03 (−0.37, 0.31) | 0.865 | 0.00 (−0.34, 0.33) | 0.984 | 0.01 (−0.36, 0.38) | 0.963 | 0.02 (−0.41, 0.46) | 0.916 | |

| 50s | 0.00 (−0.34, 0.34) | 1.000 | 0.34 (0.00, 0.67) | 0.047 | 0.10 (−0.27, 0.47) | 0.595 | −0.20 (−0.64, 0.23) | 0.359 | |

| ≥60s | 0.39 (−0.07, 0.86) | 0.099 | 0.89 (0.43, 1.35) | 0.000 | 0.59 (0.07, 1.10) | 0.025 | −0.61 (−1.21, −0.01) | 0.047 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | 0.48 (0.24, 0.72) | 0.000 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.73) | 0.000 | 0.67 (0.40, 0.94) | 0.000 | −0.40 (−0.71, −0.08) | 0.013 | |

| Providing in-home care | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −0.37 (−0.83, 0.10) | 0.125 | −0.06 (−0.52, 0.39) | 0.785 | −0.29 (−0.80, 0.22) | 0.269 | 0.39 (−0.21, 0.99) | 0.206 | |

| Number of children | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) | 0.599 | 0.21 (0.09, 0.34) | 0.001 | 0.15 (0.01, 0.29) | 0.038 | 0.06 (−0.10, 0.23) | 0.459 | |

| Menstrual problems | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | 0.22 (−0.06, 0.49) | 0.120 | 0.28 (0.01, 0.54) | 0.041 | 0.18 (−0.12, 0.47) | 0.245 | 0.04 (−0.31, 0.38) | 0.837 | |

| Mental health problems/ insomnia | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −1.27 (−1.54, −0.99) | 0.000 | −1.29 (−1.56, −1.03) | 0.000 | −1.51 (−1.81, −1.21) | 0.000 | 1.90 (1.55, 2.26) | 0.000 | |

| Anemia | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −0.11 (−0.47, 0.25) | 0.539 | 0.08 (−0.27, 0.44) | 0.638 | 0.16 (−0.24, 0.55) | 0.443 | −0.14 (−0.61, 0.32) | 0.542 | |

| Headaches | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −0.21 (−0.47, 0.06) | 0.123 | 0.02 (−0.24, 0.28) | 0.861 | 0.02 (−0.27, 0.32) | 0.867 | 0.07 (−0.27, 0.41) | 0.689 | |

| Gastrointestinal problems | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −0.16 (−0.44, 0.13) | 0.283 | −0.29 (−0.57, −0.01) | 0.044 | −0.43 (−0.74, −0.12) | 0.007 | 0.24 (−0.12, 0.61) | 0.194 | |

| Eating/feeding problems | |||||||||

| No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Yes | −0.46 (−0.78, −0.15) | 0.004 | −0.29 (−0.60, 0.02) | 0.071 | −0.24 (−0.59, 0.11) | 0.184 | 0.10 (−0.31, 0.51) | 0.624 | |

| Income × Age group | |||||||||

| Income × 20s | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × 30s | 0.09 (−0.01, 0.19) | 0.072 | 0.09 (0.00, 0.19) | 0.058 | −0.01 (−0.12, 0.09) | 0.795 | −0.16 (−0.29, −0.04) | 0.012 | |

| Income × 40s | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) | 0.511 | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) | 0.560 | −0.05 (−0.15, 0.06) | 0.380 | −0.14 (−0.26, −0.02) | 0.021 | |

| Income × 50s | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.15) | 0.225 | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.10) | 0.852 | −0.03 (−0.13, 0.07) | 0.566 | −0.12 (−0.24, 0.00) | 0.050 | |

| Income × ≥60s | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.17) | 0.527 | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.09) | 0.587 | −0.09 (−0.24, 0.05) | 0.192 | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.09) | 0.369 | |

| Income × Marital status | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.09) | 0.537 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.08) | 0.563 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.10) | 0.503 | 0.05 (−0.04, 0.13) | 0.266 | |

| Income × Providing in-home care | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | −0.19 (−0.31, −0.07) | 0.001 | −0.25 (−0.36, −0.14) | 0.000 | −0.19 (−0.32, −0.07) | 0.003 | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.17) | 0.746 | |

| Income × Number of children | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.01) | 0.142 | −0.04 (−0.07, −0.01) | 0.005 | −0.04 (−0.07, −0.01) | 0.024 | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.816 | |

| Income × Menstrual problems | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.05) | 0.581 | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | 0.186 | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | 0.826 | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.09) | 0.917 | |

| Income × Mental health problems/insomnia | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.06 (−0.02, 0.13) | 0.148 | 0.08 (0.01, 0.16) | 0.027 | 0.08 (0.00, 0.17) | 0.043 | −0.09 (−0.19, 0.00) | 0.059 | |

| Income × Anemia | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.11) | 0.802 | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) | 0.777 | −0.02 (−0.13, 0.08) | 0.651 | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) | 0.504 | |

| Income × Headaches | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.10) | 0.434 | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | 0.961 | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.06) | 0.569 | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.07) | 0.701 | |

| Income × Gastrointestinal problems | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.10) | 0.614 | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.13) | 0.166 | 0.08 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.062 | −0.03 (−0.13, 0.07) | 0.569 | |

| Income × Eating/Feeding problems | |||||||||

| Income × No | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | Ref. - | - | |

| Income × Yes | 0.06 (−0.03, 0.15) | 0.164 | 0.05 (−0.03, 0.14) | 0.229 | 0.07 (−0.03, 0.16) | 0.156 | −0.01 (−0.12, 0.10) | 0.894 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suzuki, T.; Sasayama, K.; Nishimura, E.; Yamaji, N.; Ota, E.; Saito, E.; Yoneoka, D. Association Between Income and Well-Being Among Working Women in Japan. Healthcare 2025, 13, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030240

Suzuki T, Sasayama K, Nishimura E, Yamaji N, Ota E, Saito E, Yoneoka D. Association Between Income and Well-Being Among Working Women in Japan. Healthcare. 2025; 13(3):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030240

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuzuki, Takao, Kiriko Sasayama, Etsuko Nishimura, Noyuri Yamaji, Erika Ota, Eiko Saito, and Daisuke Yoneoka. 2025. "Association Between Income and Well-Being Among Working Women in Japan" Healthcare 13, no. 3: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030240

APA StyleSuzuki, T., Sasayama, K., Nishimura, E., Yamaji, N., Ota, E., Saito, E., & Yoneoka, D. (2025). Association Between Income and Well-Being Among Working Women in Japan. Healthcare, 13(3), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030240

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)