The COVID-19 Pandemic and Acute Coronary Syndrome Admissions and Deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

Highlights

- We evaluated the impact of COVID-19 on heart disease hospitalizations and deaths using data from Allegheny County (population 1.2 million) from January 2017 to November 2020.

- During the pandemic, heart disease hospitalizations decreased by 14.8% and heart disease deaths increased by 2.4%

- The COVID-19 pandemic minimally impacted overall heart disease trends.

- Interpreting changes in heart disease hospitalizations and death during the pandemic must be done in the context of long-term trends.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACHD | Allegheny County Health Department |

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AMI | Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LTCF | Long-Term Care Facility |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| PA | Pennsylvania |

| STEMI | ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| US | United States |

References

- Kiss, P.; Carcel, C.; Hockham, C.; Peters, S. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the care and management of patients with acute cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2020, 7, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Seidu, S.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Cos, X.; Khunti, K. Indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitalisations for cardiometabolic conditions and their management: A systematic review. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 653–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, A.; Shahin, L.; Abdelsalam, M.; Ibrahim, M. Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the rate of acute coronary syndrome admissions: A comprehensive review of published literature. Open Heart 2021, 8, e001645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Kazmi, S.K.; Khan, F.M.A.; Natoli, V.; Hunain, R.; Islam, Z.; Costa, A.C.D.S.; Ahmad, S.; Essar, M.Y. Viral hepatitis amidst COVID-19 in Africa: Implications and recommendations. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghita, R.; Soldanescu, I.; Lobiuc, A.; Sturdza, O.A.C.; Filip, R.; Constantinescu-Bercu, A.; Dimian, M.; Mangul, S.; Covasa, M. The knowns and unknowns of long COVID-19: From mechanisms to therapeutic approaches. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1344086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, A.S.; Moscone, A.; McElrath, E.E.; Varshney, A.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Liao, K.P.; Solomon, S.D.; Vaduganathan, M. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer, J.D.; Barnato, A.; Birkmeyer, N.; Bessler, R.; Skinner, J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braiteh, N.; Rehman, W.U.; Alom, M.; Skovira, V.; Gross, N.; Garan, A.; Meyerwaerts, S.; Giedrimiene, D.; Cavallera, S.; Sanborn, T.A. Decrease in acute coronary syndrome presentations during the COVID-19 pandemic in upstate New York. Am. Heart J. 2020, 226, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- de Havenon, A.; Ney, J.P.; Callaghan, B.; Kerber, K.A.; Stulberg, E.; Saini, V.; Majersik, J.J.; Muller, N.; Tirschwell, D.L.; Burke, J.F. Characteristics and outcomes among us patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, U.N.; Reimer, A.P.; Brown, A.; Van Ittersum, W.; Ghafari, G.; Mansour, M.; Starling, R.C.; Kapadia, S.R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on critical care transfers for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, stroke, and aortic emergencies. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 13, e006938. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.N.; Kelsey, M.D.; Kelsey, A.M.; Wang, T.Y.; Thomas, K.L.; Zhang, S.; Montgomery, M.L.; Smith, A.S.; Washam, J.B.; Greene, S.J. Acute cardiovascular hospitalizations and illness severity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Dyer, S.; Salvia, J.; Segal, L.; Levi, R. Worse cardiac arrest outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Boston can be attributed to patient reluctance to seek care. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, R.; Fukamachi, D.; Ebuchi, Y.; Ayabe, K.; Murata, N.; Morikawa, M.; Yanagida, T.; Okumura, Y. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on hospitalizations and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction in a Japanese single center. Heart Vessels 2021, 36, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruoha, S.; Yosefy, C.; Gallego-Colon, E.; Reuveni, H.; Peled, R. Impact in total ischemic time and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction admissions during COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, S.; Spaccarotella, C.; Basso, C.; Calabro, M.P.; Curcio, A.; Filardi, P.P.; Mancone, M.; Mercuro, G.; Musumeci, G.; Romeo, F. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-1S19 era. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsner, L.A.; Kampf, M.O.; Seuchter, S.A.; Gruendner, J.; Gulden, C.; Ganslandt, T.; Schulz, S.; Bergh, B.; Loffler, M.; Semler, S.C. Reduced rate of inpatient hospital admissions in 18 German university hospitals during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 594117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafham, M.M.; Spata, E.; Goldacre, R.; Gair, D.; Curnow, P.; Luker, M.; Gale, C.P.; Casadei, B.; Baigent, C. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet 2020, 396, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makaris, E.; Kourek, C.; Karatzanos, E.; Kalantzis, C.; Gialafos, E.; Anyfantakis, Z.; Latsos, G.; Panagiotakos, D.; Nanas, S. Reduction of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) hospital admissions in the region of Messinia in Greece during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Hellenic. J. Cardiol. 2021, 62, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.K.; Paik, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, S. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on emergency care utilization in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A nationwide population-based study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecker, S.; Jones, S.; Petrilli, C.M.; Admon, A.J.; Weerahandi, H.; Francois, F.; Horwitz, L.I. Hospitalizations for chronic disease and acute conditions in the time of COVID-19. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, K.A.; Blue, L.; Kranker, K.; Atasoy, S.; Chen, J.J.; Hernandez-Viveros, J.; Zurovac, J.; Moreno, L.; Shrank, W.H. Hospital use for myocardial infarction and stroke among Medicare beneficiaries from March to December 2020. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1340–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiffert, M.; Brunner, F.J.; Remmel, M.; Thomalla, G.; Marschall, U.; L’Hoest, H.; Blankenberg, S.; Westermann, D.; Gerloff, C. Temporal trends in the presentation of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: An analysis of health insurance claims. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Dehghani, P.; Grines, C.; Davidson, L.; Nayak, K.R.; Sawlani, N.; Alraies, M.C.; Jaffer, F.A.; Schmidt, C.W.; Lyas, S. Initial findings from the North American COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.; Banerjee, A.; Berry, C.; Boyle, J.R.; Bray, B.; Bradlow, W.; Cohen, A.; de Belder, M.; Deanfield, J.; De Stavola, B. Monitoring indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on services for cardiovascular diseases in the UK. Heart 2020, 106, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarifar, M.; Ghavami, M.; Poorhosseini, H.; Abbasi, A.; Kassaian, S.E.; Hosseini, K.; Mortazavi, S.H.; Alidoosti, M.; Aghajani, H.; Hajizeinali, A. Management and outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during coronavirus 2019 pandemic in a center with 24/7 primary angioplasty capability. Kardiol. Pol. 2020, 78, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, A.; Vio, R.; Rivezzi, F.; Schiavo, A.; Sarto, P.; Basso, C.; Sabino, G.; Tarantini, G.; Iliceto, S. Characteristics and hospital course of patients admitted for acute cardiovascular diseases during the coronavirus disease-19 outbreak. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primessnig, U.; Pieske, B.M.; Sherif, M. Increased mortality and worse cardiac outcome of acute myocardial infarction during the early COVID-19 pandemic. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.; Meisinger, C.; Kirchberger, I.; Thilo, C.; Linseisen, J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on myocardial infarction care. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.C.; Lundberg, D.J.; Elo, I.T.; Hempstead, K.; Bor, J.; Preston, S.H. COVID-19 and excess mortality in the United States: A county-level analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, M.; Pharis, M.; Gulino, S.P.; Robbins, J.M.; Bettigole, C. Excess mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Philadelphia. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhera, R.K.; Shen, C.; Gondi, S.; Chen, S.; Kazi, D.S.; Yeh, R.W. Cardiovascular deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Anderson, R.N. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA 2021, 325, 1829–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchner, H.; Fontanarosa, P.B. Excess deaths and the Great Pandemic of 2020. JAMA 2020, 324, 1504–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, M.S.; Almeida, J.S.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Albert, P.S.; Freedman, N.D.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A. Impact of population growth and aging on estimates of excess U.S. deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to August 2020. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, H.M.; Normand, S.T.; Wang, Y. Twenty-year trends in outcomes for older adults with acute myocardial infarction in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.C.; Kanter, M.H.; Li, B.H.; Reading, S.R.; Harrison, T.N.; Scott, R.D.; Reynolds, K. Trends in acute myocardial infarction by race and ethnicity. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e013542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, E.O.; Rager, J.R.; Brink, L.L.; Benson, S.; Marshall, L.P.; Logue, J.N.; Sharma, R.K. Trends in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization rates for US States in the CDC tracking network. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degano, I.R.; Salomaa, V.; Veronesi, G.; Ferrieres, J.; Kirchberger, I.; Laksmanan, S.; Peters, A.; Havulinna, A.S.; Rimm, E.B.; Tunstall-Pedoe, H. Twenty-five-year trends in myocardial infarction attack and mortality rates, and case-fatality, in six European populations. Heart 2015, 101, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioacara, S.; Popescu, A.C.; Tenenbaum, J.; Popescu, R.; Istrate, A.; Sirbu, A.; Fica, S. Acute myocardial infarction mortality rates and trends in Romania between 1994 and 2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015, 15, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/alleghenycountypennsylvania (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- United States Census Bureau. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates; 2019: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles; TableID: DP05. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=0500000US42003&tid=ACSDP5Y2019.DP05 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Solomon, M.D.; McNulty, E.J.; Rana, J.S.; Leong, T.K.; Lee, C.; Sung, S.H.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Sidney, S.; Go, A.S. The COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.; Bisquera, A.; Lunt, A.; Peacock, J.L.; Greenough, A. Outcomes of the Neonatal Trial of High-Frequency Oscillation at 16 to 19 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofti, A.S.; Capatina, A.; Kugelmass, A.D. Assessment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction volume trends during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 131, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Hwang, J. No reduction of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction admission in Taiwan during coronavirus pandemic. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 131, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckman, T.J.; Wilson, M.A.; Chiu, S.T.; Penny, B.W.; Chepuri, V.B.; Waggoner, J.W.; Wang, L. Case rates, treatment approaches, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattka, M.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Winsauer, C.; Abuarab, S.; Baumhardt, M.; Behnke, A.; Geyer, S.; Hecht, M.; Herden, J.; Keßler, M. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality of patients with STEMI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2021, 107, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, H.; Bruch, L.; Maier, B.; Schuhlen, H. Acute myocardial infarction admissions in Berlin during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.A.; Koul, S.; Olivecrona, G.K.; Götberg, M.; Tydén, P.; Rydberg, E.; Grimfjärd, P.; James, S.; Erlinge, D. Incidence and outcome of myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide registry-based study. Lancet 2020, 396, 10260. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, G.A.; Wei, G.S.; Sorlie, P.D.; Fine, L.J.; Rosenberg, Y.; Adams-Campbell, L.L.; Wright, J.T. Decline in Cardiovascular Mortality: Possible Causes and Implications. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, A.T.; Danagoulian, S.; Venkatesh, A.K.; Levy, P.D. Medicaid expansion and resource utilization in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2586–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modin, D.; Claggett, B.; Sindet-Pedersen, C.; Lassen, M.C.H.; Skaarup, K.G.; Jensen, J.U.; Fralick, M.; Schou, M.; Lamberts, M.; Gislason, G. Acute COVID-19 and the incidence of ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2020, 142, 2080–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsoularis, I.; Fonseca-Rodríguez, O.; Farrington, P.; Lindmark, K.; Fors Connolly, A.-M. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke following COVID-19 in Sweden: A self-controlled case series and matched cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pandemic n = 11,913 | Pandemic n = 2170 | Pre-Pandemic n = 7006 | Pandemic n = 1351 | Pre-Pandemic n = 4482 | Pandemic n = 819 | |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 68.5 (13.4) | 67.4 (13.3) | 66.8 (13.1) | 65.8 (12.9) | 71.0 (13.5) | 70.0 (13.5) |

| Age Group, years (n, %) | ||||||

| <45 | 442 (3.7) | 106 (4.9) | 306 (4.4) | 70 (5.2) | 134 (3.0) | 36 (4.4) |

| 45–64 | 4016 (33.7) | 790 (36.4) | 2748 (39.2) | 555 (41.1) | 1257 (28.1) | 235 (28.7) |

| 65–74 | 3174 (26.6) | 627 (28.9) | 1944 (27.8) | 390 (28.9) | 1215 (27.1) | 237 (28.9) |

| ≥75 | 3909 (32.8) | 647 (29.8) | 2008 (28.7) | 336 (24.9) | 1876 (41.9) | 311 (38.0) |

| Missing | 372 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sex (n, %) | ||||||

| Men | 7006 (58.8) | 1351 (62.3) | - | - | - | - |

| Women | 4482 (37.6) | 819 (37.7) | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 425 (3.6) | 0 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Race (n, %) | ||||||

| White | 9950 (83.5) | 1882 (86.7) | 6179 (88.2) | 1186 (87.8) | 3771 (84.1) | 696 (85.0) |

| Non-White | 1244 (10.4) | 230 (10.6) | 622 (8.9) | 123 (9.1) | 622 (13.9) | 107 (13.1) |

| Missing | 719 (6.0) | 58 (2.7) | 205 (2.9) | 42 (3.1) | 89 (2.0) | 16 (2.0) |

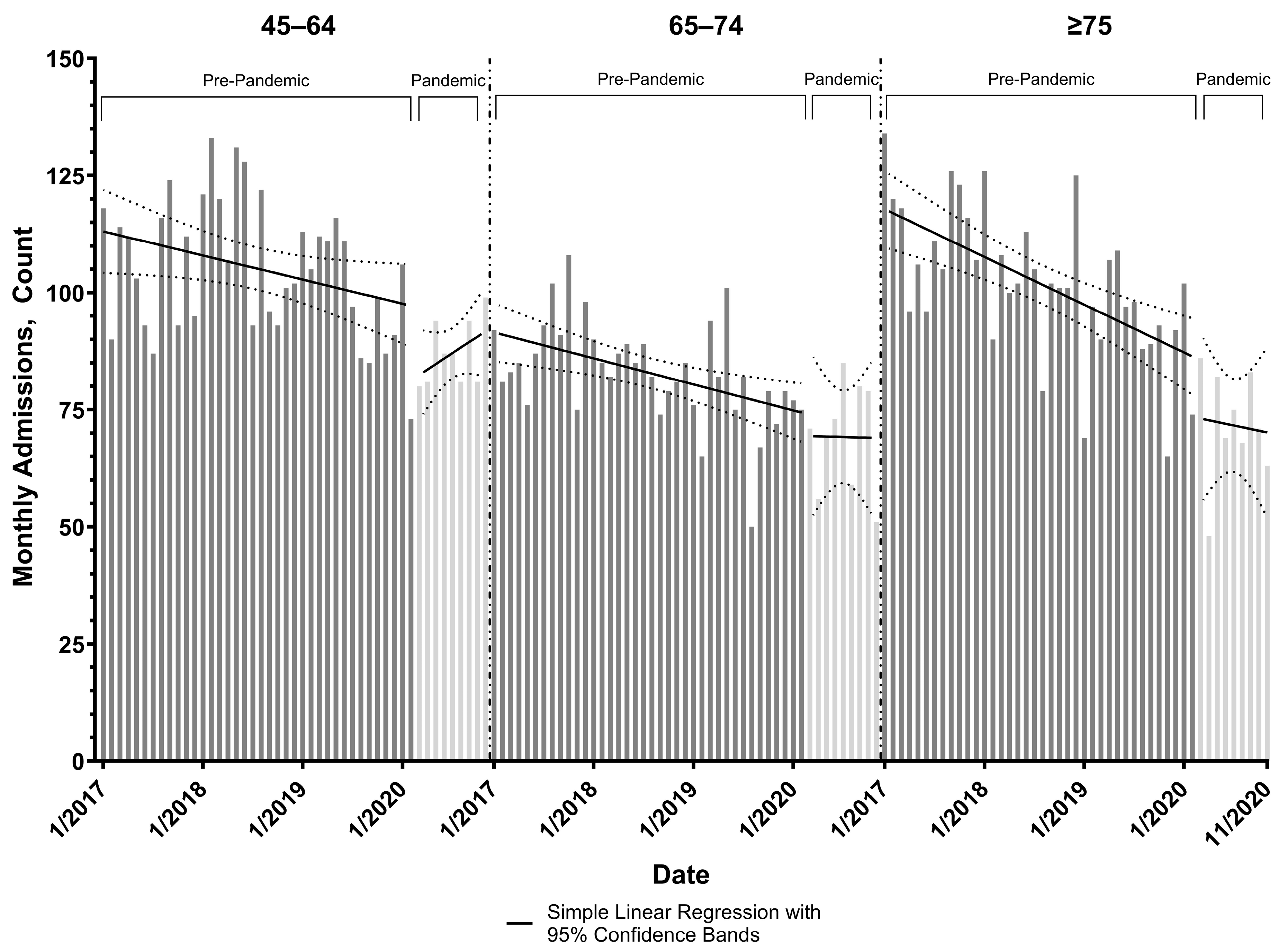

| Age Group | Coefficient | Coefficient V95. | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Pre-Pandemic 1 Slope | −2.92 | −3.64, −2.21 |

| Change in Admission Volume at Start of Pandemic | −20.50 | −51.91, 10.91 | |

| Post-Pandemic 1 Slope Minus Pre- | 4.21 | −0.75, 9.17 | |

| <45 | Pre-Pandemic 1 Slope | −0.01 | −0.11, 0.10 |

| Change in Admission Volume at Start of Pandemic | −2.71 | −6.35, 0.94 | |

| Post-Pandemic 1 Slope Minus Pre- | 0.74 | 0.18, 1.30 | |

| 45–64 | Pre-Pandemic 1 Slope | −0.43 | −0.85, −0.01 |

| Change in Admission Volume at Start of Pandemic | −14.35 | −24.48, −4.22 | |

| Post-Pandemic 1 Slope Minus Pre- | 1.60 | 0.33, 2.86 | |

| 65–74 | Pre-Pandemic 1 Slope | −0.46 | −0.77, −0.15 |

| Change in Admission Volume at Start of Pandemic | −4.52 | −17.39, 8.35 | |

| Post-Pandemic 1 Slope Minus Pre- | 0.41 | −2.41, 3.24 | |

| ≥75 | Pre-Pandemic 1 Slope | −0.85 | −1.23, −0.47 |

| Change in Admission Volume at Start of Pandemic | −12.40 | −27.78, 2.98 | |

| Post-Pandemic 1 Slope Minus Pre- | 0.48 | −1.88, 2.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herbert, B.M.; Poornima, I.G.; Mulukutla, S.R.; Ma, Z.-q.; Brink, L.; Chang, Y.; Sekikawa, A.; Kuller, L.H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Acute Coronary Syndrome Admissions and Deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243303

Herbert BM, Poornima IG, Mulukutla SR, Ma Z-q, Brink L, Chang Y, Sekikawa A, Kuller LH. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Acute Coronary Syndrome Admissions and Deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243303

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerbert, Brandon M., Indu G. Poornima, Suresh R. Mulukutla, Zhen-qiang Ma, LuAnn Brink, Yuefang Chang, Akira Sekikawa, and Lewis H. Kuller. 2025. "The COVID-19 Pandemic and Acute Coronary Syndrome Admissions and Deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243303

APA StyleHerbert, B. M., Poornima, I. G., Mulukutla, S. R., Ma, Z.-q., Brink, L., Chang, Y., Sekikawa, A., & Kuller, L. H. (2025). The COVID-19 Pandemic and Acute Coronary Syndrome Admissions and Deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Healthcare, 13(24), 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243303