Positive Mental Health, Anxiety and Prenatal Bonding: A Contextual Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Variables of Interest

3.3. Analysis of Possible Covariates

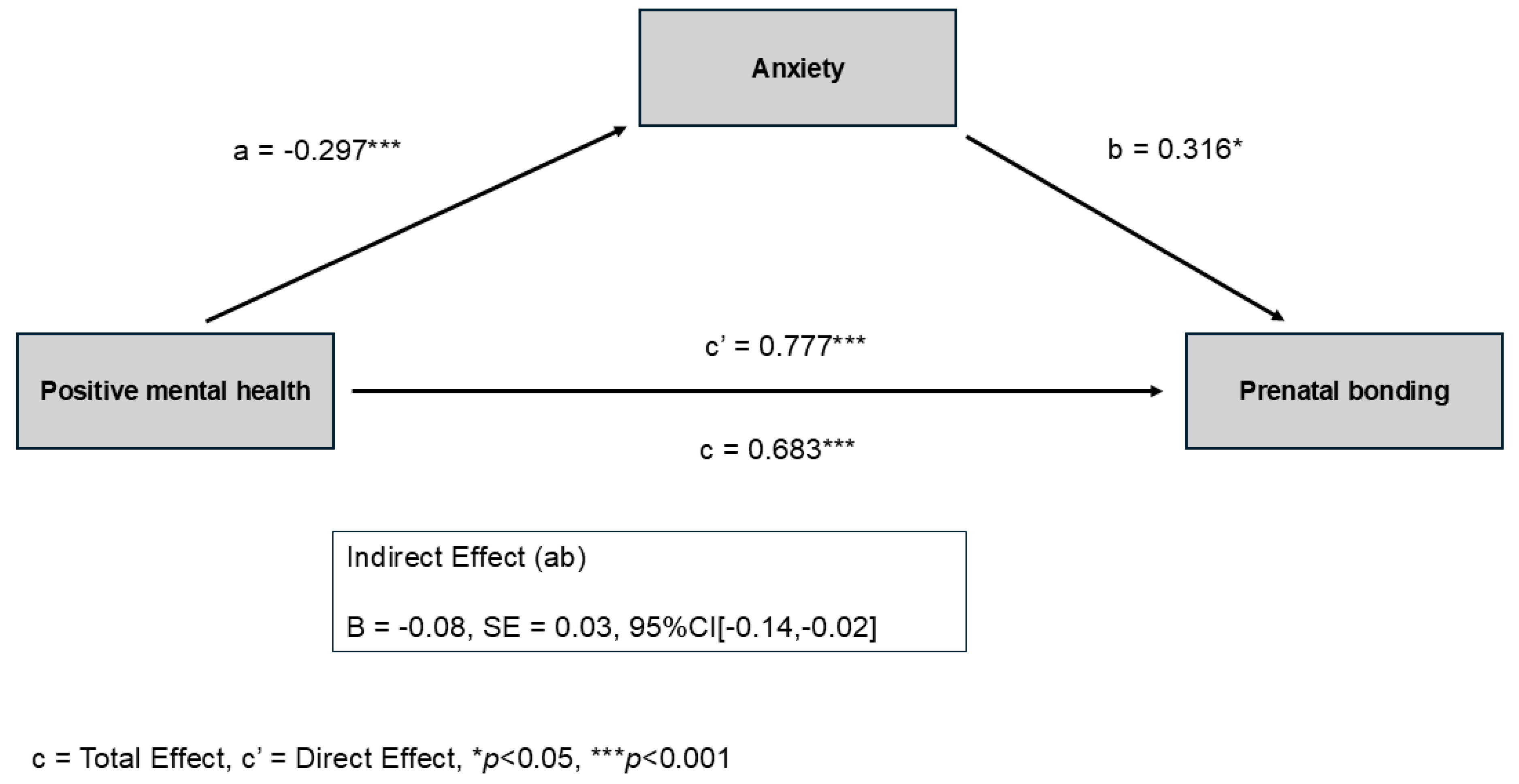

3.4. Theoretical Proposed Model

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMH | Positive Mental Health |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

References

- Chauhan, A.; Potdar, J. Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelica, A.; Cetkovic, N.; Trninic-Pjevic, A.; Mladenovic-Segedi, L. The Phenomenon of Pregnancy—A Psychological View. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Sharma, K.; Martin, S.L.; Thompson, P.M.; Reddy, S.Y. Associations of Mental Disorders with Maternal Health Outcomes. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunton, R.; Simpson, N.; Dryer, R. Pregnancy-Related Anxiety, Perceived Parental Self-Efficacy and the Influence of Parity and Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal Mental Health: A Review of Progress and Challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Martínez, C.; Val, V.A.; Murphy, M.; Busquets, P.C.; Sans, J.C. Relation between Positive and Negative Maternal Emotional States and Obstetrical Outcomes. Women Health 2011, 51, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, A.-K.; Lahti, M.; Kuusinen, T.; Tuovinen, S.; Villa, P.; Hämäläinen, E.; Laivuori, H.; Kajantie, E.; Räikkönen, K. Maternal Prenatal Positive Affect, Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms and Birth Outcomes: The PREDO Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdepuro, A.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Girchenko, P.; Villa, P.M.; Heinonen, K.; Lahti, J.; Pyhälä, R.; Laivuori, H.; Kajantie, E.; Räikkönen, K. Positive Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy and Psychiatric Problems in Children from Early Childhood to Late Childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2024, 36, 1903–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Ferré-Grau, C.; Canut, T.L.; Pires, R.; Carvalho, J.C.; Ribeiro, I.; Sequeira, C.; Rodrigues, T.; Sampaio, F.; Costa, T.; et al. Positive Mental Health in University Students and Its Relations with Psychological Vulnerability, Mental Health Literacy, and Sociodemographic Characteristics: A Descriptive Correlational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental Illness and/or Mental Health? Investigating Axioms of the Complete State Model of Health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, M. Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Lluch-Canut, M. Construcción de una Escala para Evaluar la Salud Mental Positiva [Internet]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona, Facultad de Psicología, Barcelona, Spain, 1999. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/2366/E_TESIS.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Lluch-Canut, M.T. Salud Mental Positiva. Cuidar la Salud Mental Positiva, en el Contexto de la Pandemia COVID-19 y Hacía un Futuro Denominado “Nueva Normalidad”. Hermeneutic 2021, 19, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C.; Carvalho, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.; Nogueira, M.J.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Roldán-Merino, J. Levels of Positive Mental Health in Portuguese and Spanish Nursing Students. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Canut, T.; Puig-Llobet, M.; Sánchez-Ortega, A.; Roldán-Merino, J.; Ferré-Grau, C.; Positive Mental Health Research Group. Assessing Positive Mental Health in People with Chronic Physical Health Problems: Correlations with Sociodemographic Variables and Physical Health Status. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrosa-Castro, Á.; Romero-Martínez, S.; Monterrosa-Blanco, A. Positive Maternal Mental Health in Pregnant Women and Its Association with Obstetric and Psychosocial Factors. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kestel, D.; Dua, T. WHO Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240057142 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Davis, E.P.; Narayan, A.J. Pregnancy as a Period of Risk, Adaptation, and Resilience for Mothers and Infants. Dev. Psychopathol. 2020, 32, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zheng, H.; Bao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Feng, Y. Joint Developmental Trajectories of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Their Predictors: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Clinical Consensus-Obstetrics; Gantt, A.; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Metz, T.D.; Kuller, J.A.; Louis, J.M.; Cahill, A.G.; Turrentine, M.A.; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetric Care Consensus #11, Pregnancy at Age 35 Years or Older. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, B25–B40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, A.; Paffoni, A.; Viganò, P. Does Maternal Age Affect Assisted Reproduction Technology Success Rates after Euploid Embryo Transfer? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Fossé, N.A.; van der Hoorn, M.P.; van Lith, J.M.M.; le Cessie, S.; Lashley, E.E.L.O. Advanced Paternal Age Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Spontaneous Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 650–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.; Obst, S.; Teague, S.J.; Rossen, L.; Spry, E.A.; Macdonald, J.A.; Sunderland, M.; Olsson, C.A.; Youssef, G.; Hutchinson, D. Association between Maternal Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Child and Adolescent Development: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; De Asis-Cruz, J.; Limperopoulos, C. Brain Structural and Functional Outcomes in the Offspring of Women Experiencing Psychological Distress during Pregnancy. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 2223–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bas, J.; Youssef, G.; Macdonald, J.A.; Teague, S.; Mattick, R.; Honan, I.; McIntosh, J.E.; Khor, S.; Rossen, L.; Elliot, E.J.; et al. The Role of Antenatal and Postnatal Maternal Bonding in Infant Development. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 820–829.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olza, I.; Fernández, L. Psicología del Embarazo; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roncallo, C.P.; Sánchez de Miguel, M.; Arranz Freijo, E. Vínculo Materno-Fetal: Implicaciones en el Desarrollo Psicológico y Propuesta de Intervención en Atención Temprana. Escr. Psicol. 2015, 8, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanen, E.; Vierikko, E.; Kojo, T.; Lahikainen, A.R.; Pölkki, P.; Paavonen, E.J. Prenatal Expectations and Other Psycho-Social Factors as Risk Factors of Postnatal Bonding Disturbance. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C.; Carvalho, J.C.; Roldan-Merino, J.; Moreno-Poyato, A.R.; Teixeira, S.; David, B.; Costa, P.S.; Puig-Llobet, M.; Lluch-Canut, M.T. Psychometric Properties of the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire: Short Form (PMHQ-SF18) in Young Adults. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1375378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, M. La Escala EVAP (Evaluación de la Vinculación Afectiva y la Adaptación Prenatal). Un estudio piloto. Index Enferm. 2008, 17, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artica-Martínez, J.; Barba-Aymar, G.; Mejía-Muñoz, A.M.; Manco-Ávila, E.; Orihuela-Salazar, J. Evidencias de validez de la escala para la Evaluación de la Vinculación Afectiva y la Adaptación Prenatal (EVAP) en gestantes usuarias del INMP. Rev. Invest. Psicol. 2018, 21, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.J.; Blanch, J.; Peri, J.M.; De Pablo, J.; Pintor, L.; Bulbena, A. A Validation Study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a Spanish Population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2003, 25, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 27th ed.; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Sechi, C.; Vismara, L. Advanced Maternal Age: A Scoping Review about the Psychological Impact on Mothers, Infants, and Their Relationship. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Álvarez, L.-M.; Fernández-Félix, B.M.; Allotey, J.; Thangaratinam, S.; Zamora, J. Effects of Maternal Education on Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of 2 356 402 Pregnancies. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, E.; Stamoulou, P.; Tzanoulinou, M.-D.; Orovou, E. Perinatal Mental Health; The Role and the Effect of the Partner: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, B.; Appelbaum, M.; Beckman, L.; Dutton, M.A.; Russo, N.F.; West, C. Abortion and Mental Health: Evaluating the Evidence. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 863–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Okada, T.; Morikawa, M.; Yamauchi, A.; Sato, M.; Ando, M.; Ozaki, N. Perinatal Depression and Anxiety of Primipara Is Higher than That of Multipara in Japanese Women. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, H.; Akın, B.; Erkal Aksoy, Y. Effect of High-Risk Pregnancy on Prenatal Stress Level: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23203–23212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbally, M.; Bobevski, I.; Wynter, K.; Vollenhoven, B. Assisted Reproduction and Perinatal Emotional Wellbeing: Findings from a Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 4908–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, L.M.; Müller, M.; Doster, A.; Sohn, C.; Wallwiener, M.; Reck, C.; Wallwiener, S. Maternal-Fetal Attachment Protects against Postpartum Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Postpartum Bonding and Partnership Satisfaction. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianciardi, E.; Ongaretto, F.; De Stefano, A.; Siracusano, A.; Niolu, C. The Mother-Baby Bond: Role of Past and Current Relationships. Children 2023, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, L.; Smolík, F.; Kaźmierczak, M.; Putnam, S.P. Early Infant Temperament Shapes the Nature of Mother-Infant Bonding in the First Postpartum Year. Infant Behav. Dev. 2020, 58, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; O’Brien, L.M.; Pitts, D.S.; Sagong, C.; Arnett, L.K.; Harb, N.C.; Cheng, P.; Drake, C.L. Mother-to-Infant Bonding Is Associated with Maternal Insomnia, Snoring, Cognitive Arousal, and Infant Sleep Problems and Colic. Behav. Sleep Med. 2022, 20, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, A.; Shen, C.; López-Vicente, M.; Szekely, E.; Chong, Y.-S.; White, T.; Wazana, A. Maternal Positive Mental Health during Pregnancy Impacts the Hippocampus and Functional Brain Networks in Children. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdepuro, A.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Pyhälä, R.; Tuovinen, S.; Lahti, J.; Heinonen, K.; Laivuori, H.; Villa, P.M.; Reynolds, R.M.; Kajantie, E.; et al. Positive Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy and Mental and Behavioral Disorders in Children: A Prospective Pregnancy Cohort Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2023, 64, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, K.; Akyirem, S.; Sartori, L.; Abdul-Latif, A.-M.; Akaateba, D.; Bayrampour, H.; Daly, A.; Hadfield, K.; Abiiro, G.A. Measurement of Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Worldwide: A Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.; Fonseca, A.; Pereira, M.; Canavarro, M.C. Is Positive Mental Health and the Absence of Mental Illness the Same? Factors Associated with Flourishing and the Absence of Depressive Symptoms in Postpartum Women. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; Ali, E.; McNeil, D.A.; Benzies, K.; MacQueen, G.; Tough, S. Pregnancy-Related Anxiety: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 55, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Harder, S.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Mudra, S. The Association between Maternal–Fetal Bonding and Prenatal Anxiety: An Explanatory Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubber, S.; Reck, C.; Müller, M.; Gawlik, S. Postpartum Bonding: The Role of Perinatal Depression, Anxiety and Maternal-Fetal Bonding during Pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2015, 18, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba-Müller, E.; Craddock, S.; Carmona, S.; Hoekzema, E. Brain Plasticity in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: Links to Maternal Caregiving and Mental Health. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2019, 22, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin-Barthet, C.; Martínez-García, M.; Pretus, C.; Paternina-Die, M.; Soler, A.; Khymenets, O.; Pozo, Ó.J.; Leuner, B.; Vilarroya, O.; Carmona, S. The Transition to Motherhood: Linking Hormones, Brain and Behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, F.; Rutherford, H.J.V. Emotion Regulation during Pregnancy: A Call to Action for Increased Research, Screening, and Intervention. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2022, 25, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, N.; Benarous, X.; Decaluwe, B.; Wendland, J. Comparative Analysis of General and Pregnancy-Related Prenatal Anxiety Symptoms: Progression throughout Pregnancy and Influence of Maternal Attachment. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 45, 2389811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, E.; Teppola, T.; Pajulo, M.; Davis, E.P.; Nolvi, S.; Kataja, E.-L.; Sinervä, E.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Korja, R. Maternal Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Regulation Capacity Are Associated with the Unpredictability of Maternal Sensory Signals in Caregiving Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 564158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the Women at Risk of Antenatal Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, M.H.M.; Mendonça, C.R.; Noll, M.; de Abreu Tacon, F.S.; do Amaral, W.N. Psychosocial Aspects of Gestational Grief in Women Undergoing Infertility Treatment: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, F.; Warmelink, J.C.; Gharacheh, M. Prenatal Attachment in Pregnancy Following Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Literature Review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020, 38, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmelink, J.C.; Marissink, L.; Kroes, L.; Ranjbar, F.; Henrichs, J. What Are Antenatal Maternity Care Needs of Women Who Conceived through Fertility Treatment? A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 44, 2148099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulskienė, M.; Žemaitienė, N. Experience of Late Miscarriage and Practical Implications for Post-Natal Health Care: Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Pachas, S.L.L.; Arce-Huamani, M.A. Factors Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Women Treated for Miscarriage in the Emergency Department of a Peruvian National Hospital. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.; Young, K.; Pietrusińska, M.; MacBeth, A. The Mental Health Impact of Perinatal Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.W.; Huang, J.P.; Au, H.K.; Lin, C.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chien, L.C.; Chao, H.J.; Lo, Y.C.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Impact of Miscarriage and Termination of Pregnancy on Subsequent Pregnancies: A Longitudinal Study of Maternal and Paternal Depression, Anxiety and Eudaimonia. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moafi, F.; Momeni, M.; Tayeba, M.; Rahimi, S.; Hajnasiri, H. Spiritual Intelligence and Post-Abortion Depression: A Coping Strategy. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedle, A.; Kashubeck-West, S. Core Belief Challenge, Rumination, and Posttraumatic Growth in Women Following Pregnancy Loss. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.L.; Hernandez, A.; Robb, J.M.; Zeszutek, S.; Luong, S.; Okada, E.; Kumar, K. Spontaneous Miscarriage Management Experience: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e24269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelina, L.A.; Rachmawati, I.N.; Ungsianik, T. Dissatisfaction with the Husband Support Increases Childbirth Fear among Indonesian Primigravida. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, N.; Iram, F. Marital Satisfaction in Different Types of Marriage. Pak. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 13, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel, A.; Bayrakci, H.; Yilmaz, E.B. Self-Efficacy, Psychological Well-Being and Perceived Social Support Levels in Pregnant Women. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Dong, Q.; Chen, H. Mothers’ Parenting Stress, Depression, Marital Conflict, and Marital Satisfaction: The Moderating Effect of Fathers’ Empathy Tendency. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeishi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Kawajiri, M.; Atogami, F.; Yoshizawa, T. Associations Between Coparenting Relationships and Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Negative Bonding to Infant. Healthcare 2021, 9, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, N.; Boekhorst, M.G.B.M.; Nyklicek, I.; Pop, V.J.M. Maternal-Infant Bonding and Partner Support during Pregnancy and Postpartum: Associations with Early Child Social-Emotional Development. Infant Behav. Dev. 2023, 72, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemeskel, H.S.; Kebede, A.B.; Fetene, M.T.; Dagnaw, F.T. Mother–Infant Bonding and Its Associated Factors among Mothers in the Postpartum Period, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 893505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreffler, K.M.; Spierling, T.N.; Jespersen, J.E.; Tiemeyer, S. Pregnancy Intendedness, Maternal–Fetal Bonding, and Postnatal Maternal–Infant Bonding. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Make Mothers Matter (MMM). State of Motherhood 2024: European Roll-Out. Make Mothers Matter—MMM. 2025. Available online: https://makemothersmatter.org/mmm-state-of-motherhood-in-europe-2024/european-roll-out/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bogino Larrambebere, V.; Jurado-Guerrero, T. Empleo, familia y permisos parentales en España. Un análisis longitudinal e interseccional. Papers 2025, 110, e3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjón, L.; Lizarraga, I. Family-friendly policies and employment equality: An analysis of maternity and paternity leave equalization in Spain. Iseak 2024; Working paper 2024/3. Available online: https://iseak.eu/publicacion/la-equiparacion-de-permisos-de-paternidad-y-maternidad-y-su-impacto-en-la-desigualdad-de-genero-en-el-empleo-en-espana (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kozak, K.; Greaves, A.; Waldfogel, J.; Angal, J.; Elliott, A.J.; Fifier, W.P.; Brito, N.H. Paid Maternal Leave Is Associated with Better Language and Socioemotional Outcomes during Toddlerhood. Infancy 2021, 26, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niel, M.S.; Bhatia, R.; Riano, N.S.; de Faria, L.; Catapano-Friedman, L.; Ravven, S.; Weissman, B.; Nzodom, C.; Alexander, A.; Budde, K.; et al. The Impact of Paid Maternity Leave on the Mental and Physical Health of Mothers and Children: A Review of the Literature and Policy Implications: A Review of the Literature and Policy Implications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Hajizadeh, M.; Harper, S.; Koski, A.; Strumpf, E.C.; Heymann, J. Increased Duration of Paid Maternity Leave Lowers Infant Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Quasi-Experimental Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, T.; Giordano, M.; Santoniccolo, F.; Vismara, L.; Della Vedova, A.M.; Rollè, L. Pre-Natal Attachment and Parent-to-Infant Attachment: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 620942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available online: https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C183 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Royal Decree-Law 9/2025, Published in the Official State Gazette (Boletín Oficial del Estado) on 30 July 2025, Primarily Aims to Comply with the Requirements of European Union Law, Particularly with Regard to the Transposition of the Paid Parental Leave Provided for in Articles 8.1 and 8.3 of Directive (EU) 2019/1158 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdl/2025/07/29/9 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. Maternity Protection: Compliance with International Labour Standards; Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/maternity-protection-compliance-with-international-labour-standards (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Roncallo, C.P.; Barreto, F.B.; Sánchez de Miguel, M. Promotion of Child Development and Health from the Perinatal Period: An Approach from Positive Parenting. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corno, G.; Espinoza, M.; Baños, R.M. A Narrative Review of Positive Psychology Interventions for Women during the Perinatal Period. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 39, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, Z.; Kohan, S.; Nasiri, H.; Ehsanpour, S. The Effects of Mental Health Training Program on Stress, Anxiety, and Depression during Pregnancy. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Devane, D.; Soltani, H.; Gillespie, P.; Gates, S.; Jones, L.V.; Shennan, A.H.; Rayment-Jones, H. Midwife Continuity of Care Models versus Other Models of Care for Childbearing Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 4, CD004667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoodley, C.; McKellar, L.; Ziaian, T.; Steen, M.; Fereday, J.; Gwilt, I. The Role of Midwives in Supporting the Development of the Mother–Infant Relationship: A Scoping Review. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K.; Spiby, H.; Morrell, C.J. Developing a Complex Intervention to Support Pregnant Women with Mild to Moderate Anxiety: Application of the Medical Research Council Framework. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, M.S.; Mackinnon, D.P. Required Sample Size to Detect the Mediated Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n | % | Mean | SD | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.25 | 5.05 | 44 | 19 | ||

| Gestational week | 25.69 | 9.7 | 41 | 3 | ||

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Living with partner | 81 | 90 | ||||

| Living without partner | 9 | 10 | ||||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary education | 9 | 10 | ||||

| Secondary education | 16 | 17.8 | ||||

| University education | 52 | 57.8 | ||||

| Employment situation | ||||||

| Full-time | 62 | 68.9 | ||||

| Part-time | 15 | 16.7 | ||||

| Unemployed | 9 | 10 | ||||

| Domestic work/childcare | 4 | 4.4 | ||||

| Risky pregnancy | 11 | 12.2 | ||||

| Assisted reproductive techniques | 17 | 18.9 | ||||

| Previous pregnancies | ||||||

| None | 51 | 56.6 | ||||

| One | 35 | 38.8 | ||||

| Two | 4 | 4.4 | ||||

| Previous miscarriage | 17 | 18.9 | ||||

| Anxiety scores (HADS) | ||||||

| Normal range (score 0–7) | 65 | 72.6 | ||||

| Borderline cases (score 8–10) | 16 | 17.9 | ||||

| Severe anxiety (score ≥ 11) | 9 | 9.5 |

| Mean | SD | Range | Asy. | Kurt. | 2. | 3. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive mental health | 51.36 | 5.60 | 37–61 | −0.50 | −0.39 | −0.52 ** | 0.68 ** | |

| 2. Anxiety | 6.26 | 3.45 | 0–19 | 1.02 | 2.01 | −0.21 * | ||

| 3. Prenatal bonding | 36.21 | 5.55 | 16–44 | −1.24 | 2.04 | |||

| Positive Mental Health | Anxiety | Prenatal Bonding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working (yes/no) | ns | ns | p = 0.028 |

| Having a partner (yes/no) | p = 0.01 | ns | p = 0.03 |

| Previous abortions (yes/no) | p = 0.006 | p = 0.016 | ns |

| Risky pregnancies (yes/no) | p = 0.035 | ns | ns |

| Having a Partner | Working | Previous Abortions | Risky Pregnancy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Positive Mental Health | 51.87 (5.41) | 44.20 (3.63) | 48.85 5.81 | 52.20 (5.35) | 48.90 (3.47) | 51.70 (5.77) | ||

| Anxiety | 8.22 (4.41) | 5.73 (2.96) | ||||||

| Prenatal bonding | 36.49 (5.41) | 29.25 (5.62) | 35.77 (5.74) | 38.62 (3.64) | ||||

| DV: Anxiety | R2 | F | p | Beta | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | 0.31 | 7.063 | <0.001 | ||||||

| IV: PMH | −0.297 | 0.062 | −4.784 | <0.001 | −0.420 | −0.173 | |||

| Abortions (covariate) | 1.522 | 0.829 | 1.836 | 0.070 | −0.128 | 3.173 | |||

| With a partner (covariate) | 0.115 | 1.092 | 0.105 | 0.916 | −2.059 | 2.290 | |||

| Risky pregnancy (covariate) | 1.428 | 1.064 | 1.342 | 0.183 | −0.690 | 3.548 | |||

| Working (covariate) | 0.877 | 0.932 | 0.941 | 0.349 | −0.978 | 2.733 | |||

| DV: Baby bonding | |||||||||

| Model summary | 0.56 | 16.617 | <0.001 | ||||||

| IV: PMH | 0.777 | 0.091 | 8.556 | <0.001 | 0.596 | 0.958 | |||

| M: Anxiety | 0.316 | 0.145 | 2.179 | 0.032 | 0.026 | 0.606 | |||

| Abortions (covariate) | 0.151 | 1.088 | 0.139 | 0.889 | −2.016 | 2.319 | |||

| With a partner (covariate) | 1.952 | 1.405 | 1.389 | 0.168 | −0.844 | 4.750 | |||

| Risky pregnancy (covariate) | −2.530 | 1.384 | −1.828 | 0.071 | −5.287 | 0.226 | |||

| Working (covariate) | 2.528 | 1.205 | 2.097 | 0.039 | 0.128 | 4.928 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ballesteros-Andrés, L.X.; Luengo-González, R.; Rodríguez-Rojo, I.C.; García-Sastre, M.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; Gómez-González, J.-L.; Martínez-Hortelano, J.A.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. Positive Mental Health, Anxiety and Prenatal Bonding: A Contextual Approach. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243300

Ballesteros-Andrés LX, Luengo-González R, Rodríguez-Rojo IC, García-Sastre M, Cuesta-Lozano D, Gómez-González J-L, Martínez-Hortelano JA, Peñacoba-Puente C. Positive Mental Health, Anxiety and Prenatal Bonding: A Contextual Approach. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243300

Chicago/Turabian StyleBallesteros-Andrés, Laura Xu, Raquel Luengo-González, Inmaculada Concepción Rodríguez-Rojo, Montserrat García-Sastre, Daniel Cuesta-Lozano, Jorge-Luis Gómez-González, José Alberto Martínez-Hortelano, and Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente. 2025. "Positive Mental Health, Anxiety and Prenatal Bonding: A Contextual Approach" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243300

APA StyleBallesteros-Andrés, L. X., Luengo-González, R., Rodríguez-Rojo, I. C., García-Sastre, M., Cuesta-Lozano, D., Gómez-González, J.-L., Martínez-Hortelano, J. A., & Peñacoba-Puente, C. (2025). Positive Mental Health, Anxiety and Prenatal Bonding: A Contextual Approach. Healthcare, 13(24), 3300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243300