Knowledge and Attitude of Aseer Region Pharmacists Toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

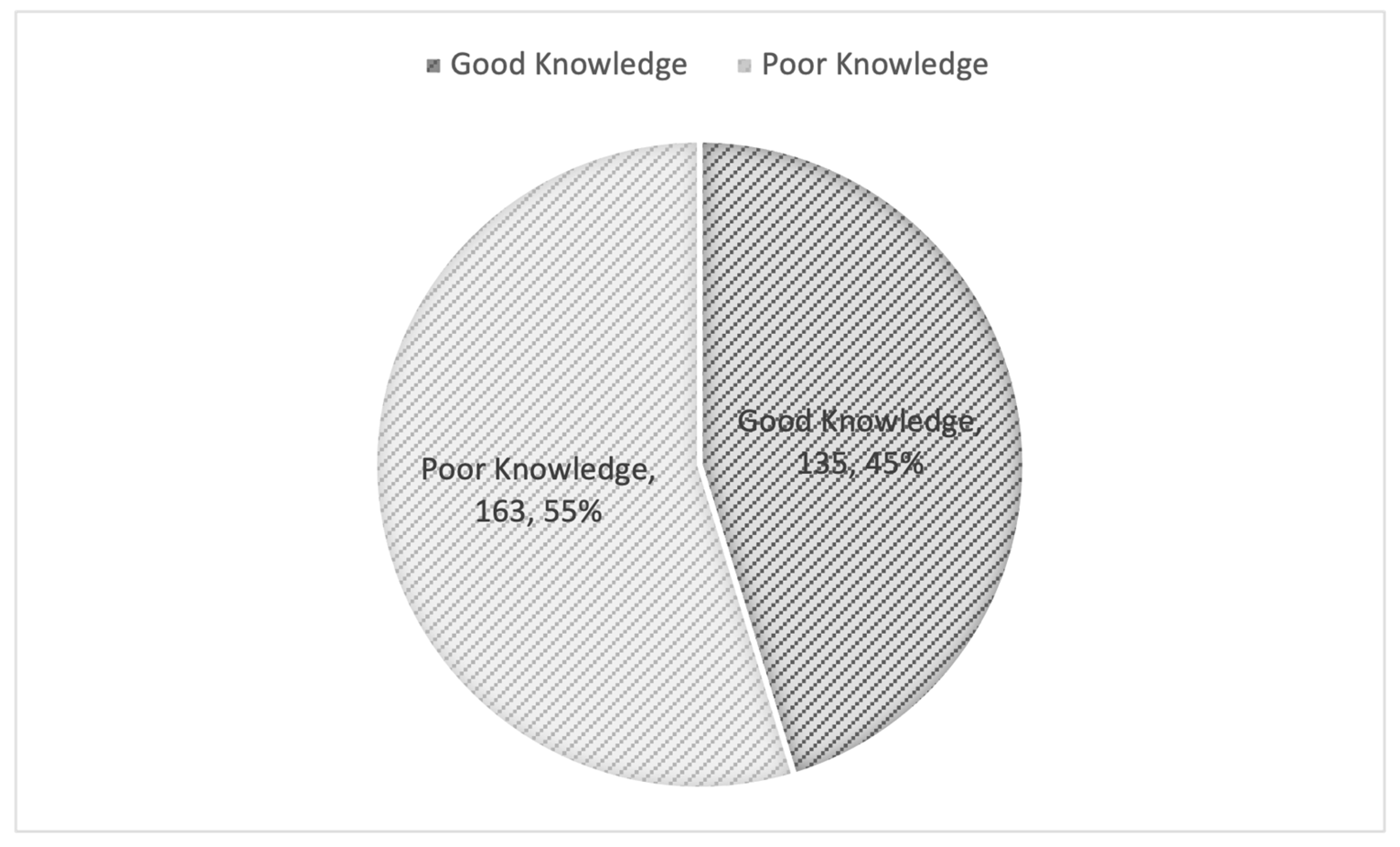

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chahine, B.; Ghandour, I.; Faddoul, L. Knowledge and attitude of community pharmacists toward biosimilar medicines: A cross-sectional study in Lebanon. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 21, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, P.; Danesi, R.; Petersel, D.; Jacobs, I. The Language of Biosimilars: Clarification, Definitions, and Regulatory Aspects. Drugs 2017, 77, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmington, A.; Dalbeth, N.; Jarrett, P.; Fraser, A.G.; Broom, R.; Browett, P.; Petrie, K.J. Medical specialists’ attitudes to prescribing biosimilars. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug 2017, 26, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S. Scientific Rationale for Waiving Clinical Efficacy Testing of Biosimilars. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 2803–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, F.; Othman, A.; El Karak, F.; Kattan, J. Review and results of a survey about biosimilars prescription and challenges in the Middle East and North Africa region. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oqal, M.; Hijazi, B.; Alqudah, A.; Al-Smadi, A.; A Almomani, B.; Alnajjar, R.; Abu Ghunaim, M.; Irshaid, M.; Husam, A. Awareness and Knowledge of Pharmacists toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Survey in Jordan. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 8080308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, J.; Bermingham, M.; Leonard, M.; Hallinan, F.; Morris, J.M.; Moore, U.; Griffin, B.T. Assessing awareness and attitudes of healthcare professionals on the use of biosimilar medicines: A survey of physicians and pharmacists in Ireland. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 88, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, I.; Pawłowski, L.; Krzyżaniak, N.; Kocić, I. Perspectives of Hospital Pharmacists Towards Biosimilar Medicines: A Survey of Polish Pharmacy Practice in General Hospitals. BioDrugs 2019, 33, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiland, P.; Batko, B.; Brzosko, M.; Kucharz, E.J.; Samborski, W.; Świerkot, J.; Więsik-Szewczyk, E.; Feldman, J. Biosimilar switching—Current state of knowledge. Reumatologia 2018, 56, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.W.; McGrath, M.K.; Dixon, M.D.; Switchenko, J.M.; Harvey, R.D.; Pentz, R.D. Academic oncology clinicians’ understanding of biosimilars and information needed before prescribing. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, R. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. Generics Biosimilars Initiat. J. 2012, 1, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, A.K.; Almalki, Z.S.; Shahid Iqbal, M.; Iqbal, M.S.; Alossaimi, M.A.; Alsaber, M.M.Z.; Alanazi, R.A.; Alruwaili, Y.M.; Altheiby, S.N.; Bin Salman, T.O. Knowledge and Attitude of Pharmacists about Biosimilar Medications in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2021, 11, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucio, S.D.; Stevenson, J.G.; Hoffman, J.M. Biosimilars: Implications for health-system pharmacists. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2013, 70, 2004–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability with a Reference Product: Update. Published Online 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/179456/download (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Iskit, A.B. Biosimilars and interchangeability: Regulatory, scientific, and global perspectives. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 213, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavell, G. Expert pharmacist roles are needed to champion medication safety. Pharm. J. 2009, 1, 330–331. [Google Scholar]

- Abusara, O.H.; Bishtawi, S.; Al-Qerem, W.; Jarrar, W.; Al-Khareisha, L.; Khdair, S.I. Pharmacists’ knowledge, familiarity, and attitudes towards biosimilar drugs among practicing Jordanian pharmacists: A cross sectional study. J. King Saud. Univ.—Sci 2023, 35, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Michel, B.; Rybarczyk-Vigouret, M.C.; Levêque, D.; Sordet, C.; Sibilia, J.; Velten, M. Knowledge, behaviors and practices of community and hospital pharmacists towards biosimilar medicines: Results of a French web-based survey. mAbs 2017, 9, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.; Hassali, M.A.; Rehman, H.; Rehman, A.U.; Muneswarao, J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards Biosimilars and Interchangeable Products: A Prescriptive Insight by the Pharmacists. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.R.; Al-Samil, A.M.; Alsayyari, A.; Yousef, C.C.; Khan, M.A.; Alhamdan, H.S.; Al-Jedai, A. The landscape of biosimilars in Saudi Arabia: Preparing for the next decade. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2023, 23, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.S. Pharmacists’ awareness and perceptions of biosimilars in Saudi Arabia. AJP 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarab, A.S.; Al-Qerem, W.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Abu Heshmeh, S.R.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Alefishat, E.; Aburuz, S. Understanding Community Pharmacists’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Biosimilar Drugs: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2025, 2025, 2248512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, S.; Sayah, R.; Mansour, M.; Nabhane, C.; Hatem, G. Assessment of community pharmacists’ knowledge of the differences between generic drugs and biosimilars: A pilot cross-sectional study. J. Med. Access 2023, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Data | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| 22–30 | 108 (36.2%) |

| 31–40 | 146 (49.0%) |

| 41–50 | 44 (14.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 214 (71.8%) |

| Female | 84 (28.2%) |

| Academic Level | |

| Bachelor B.pharm | 154 (51.7%) |

| Bachelor PharmD | 84 (28.2%) |

| Postgraduate | 60 (20.1%) |

| Experience years | |

| <5 years | 89 (29.9%) |

| 5–10 years | 91 (30.5%) |

| 11–15 years | 72 (24.2%) |

| >15 years | 46 (15.4%) |

| Place of work | |

| Public sector | 134 (45.0%) |

| Private sector | 164 (55.0%) |

| Field of work | |

| Community Pharmacies | 135 (45.3%) |

| Hospital pharmacies (Inpatients/outpatients) | 124 (41.6%) |

| Medical supply | 21 (7.0%) |

| Medical Representative or pharmaceutical company pharmacist | 18 (6.0%) |

| Knowledge Items | N (%) |

|---|---|

| A biosimilar drug has no clinically meaningful differences (similar safety and efficacy) compared to the biological reference drug. | |

| True # | 178 (59.7%) |

| False | 120 (40.3%) |

| A biosimilar has similar immunogenicity compared with the biologic reference drug. | |

| True # | 205 (68.8%) |

| False | 93 (31.2%) |

| A biosimilar drug is a generic, has same chemical structure, as the biologic reference drug. | |

| True | 173 (58.1%) |

| False # | 125 (41.9%) |

| A biosimilar drug must have the exact amino acid sequence as the biologic reference drug. | |

| True | 197 (66.1%) |

| False # | 101 (33.9%) |

| A biosimilar drug is interchangeable with the biologic reference drugs. | |

| True | 220 (73.8%) |

| False # | 78 (26.2%) |

| There is similar variability between the biologic reference drug formulation lots as there is a variability in biosimilar drug formulation lots. | |

| True # | 227 (76.2%) |

| False | 71 (23.8%) |

| All FDA-approved biosimilar drugs undergo an extensive assessment to make sure that patients can trust their efficacy, safety, and quality. | |

| True # | 270 (90.6%) |

| False | 28 (9.4%) |

| A biosimilar drug manufacturing cost is higher than that of the biologic reference drug. | |

| True | 113 (37.9%) |

| False # | 185 (62.1%) |

| A biosimilar drug is an FDA-approved version of a biologic reference drug that is manufactured after the expiry of the biologic reference drugs patent. | |

| True # | 249 (83.6%) |

| False | 49 (16.4%) |

| Knowledge score Median (IQR) | 5.00 (5.00–6.00) |

| Attitude | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| I am in favor of dispensing biosimilar drugs | 6 (2.0%) | 17 (5.7%) | 71 (23.8%) | 144 (48.3%) | 60 (20.1%) |

| I think that biosimilar drugs increase patients’ access to a variety of treatment options | 1 (0.3%) | 7 (2.3%) | 42 (14.1%) | 159 (53.4%) | 89 (29.9%) |

| I am willing to substitute a biologic reference drug with a biosimilar drug if the physician approved it | 7 (2.3%) | 16 (5.4%) | 57 (19.1%) | 142 (47.7%) | 76 (25.5%) |

| I feel that I am trained enough to dispense and counsel patients of biosimilar drugs | 18 (6.0%) | 48 (16.1%) | 79 (26.5%) | 104 (34.9%) | 49 (16.4%) |

| I think that patients should participate in taking decision to use biosimilar drugs | 10 (3.4%) | 22 (7.4%) | 64 (21.5%) | 131 (44.0%) | 71 (23.8%) |

| Factors | Overall Knowledge Level | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age in years | 0.186 | ||

| 22–30 | 65 (60.2%) | 43 (39.8%) | |

| 31–40 | 72 (49.3%) | 74 (50.7%) | |

| 41–50 | 26 (59.1%) | 18 (40.9%) | |

| Gender | 0.807 | ||

| Male | 118 (55.1%) | 96 (44.9%) | |

| Female | 45 (53.6%) | 39 (46.4%) | |

| Academic Level | 0.476 | ||

| Bachelor B.pharm | 79 (51.3%) | 75 (48.7%) | |

| Bachelor PharmD | 49 (58.3%) | 35 (41.7%) | |

| Postgraduate | 35 (58.3%) | 25 (41.7%) | |

| Experience years | 0.049 * | ||

| <5 years | 55 (61.8%) | 34 (38.2%) | |

| 5–10 years | 52 (57.1%) | 39 (42.9%) | |

| 11–15 years | 31 (43.1%) | 41 (56.9%) | |

| >15 years | 25 (54.3%) | 21 (45.7%) | |

| Work sector | 0.869 | ||

| Public sector | 74 (55.2%) | 60 (44.8%) | |

| Private sector | 89 (54.3%) | 75 (45.7%) | |

| Field of work | 0.048 * ^ | ||

| Community Pharmacies | 77 (57.0%) | 58 (43.0%) | |

| Hospital pharmacies (Inpatients/outpatients) | 67 (54.0%) | 57 (46.0%) | |

| Medical Representative or pharmaceutical company pharmacist | 9 (50.0%) | 9 (50.0%) | |

| Medical supply | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (52.4%) | |

| Attitude | Overall Knowledge Level | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | ||||||

| Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| I am in favor of dispensing biosimilar drugs | 13 (8.0%) | 46 (28.2%) | 104 (63.8%) | 10 (7.4%) | 25 (18.5%) | 100 (74.1%) | 0.049 * |

| I think that biosimilar drugs increase patients’ access to a variety of treatment options | 6 (3.7%) | 22 (13.5%) | 135 (82.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 20 (14.8%) | 113 (83.7%) | 0.490 |

| I am willing to substitute a biologic reference drug with a biosimilar drug if the physician approves it | 12 (7.4%) | 35 (21.5%) | 116 (71.2%) | 11 (8.1%) | 22 (16.3%) | 102 (75.6%) | 0.525 ^ |

| I feel that I am trained enough to dispense and counsel patients about biosimilar drugs | 32 (19.6%) | 46 (28.2%) | 85 (52.1%) | 34 (25.2%) | 33 (24.4%) | 68 (50.4%) | 0.479 ^ |

| I think that patients should participate in deciding to use biosimilar drugs | 18 (11.0%) | 33 (20.2%) | 112 (68.7%) | 14 (10.4%) | 31 (23.0%) | 90 (66.7%) | 0.848 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqahtani, S.; Almanasef, M. Knowledge and Attitude of Aseer Region Pharmacists Toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Descriptive Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243295

Alqahtani S, Almanasef M. Knowledge and Attitude of Aseer Region Pharmacists Toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Descriptive Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243295

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqahtani, Saeed, and Mona Almanasef. 2025. "Knowledge and Attitude of Aseer Region Pharmacists Toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Descriptive Study" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243295

APA StyleAlqahtani, S., & Almanasef, M. (2025). Knowledge and Attitude of Aseer Region Pharmacists Toward Biosimilar Medicines: A Descriptive Study. Healthcare, 13(24), 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243295