A New Model for Bone Health Management in Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy—The Predict & Prevent Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

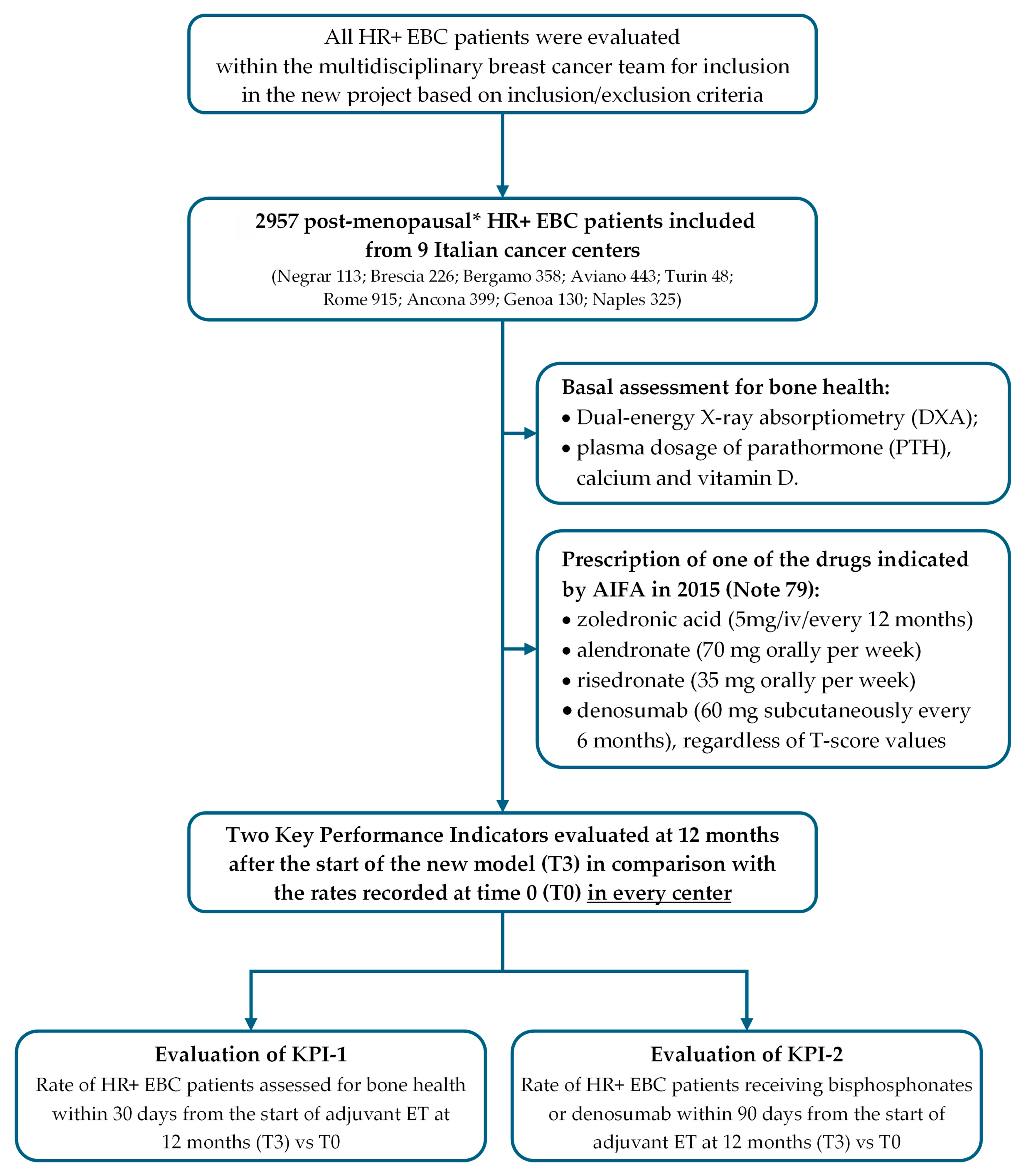

2. Materials and Methods

- Training of breast multidisciplinary teams and bone health specialists;

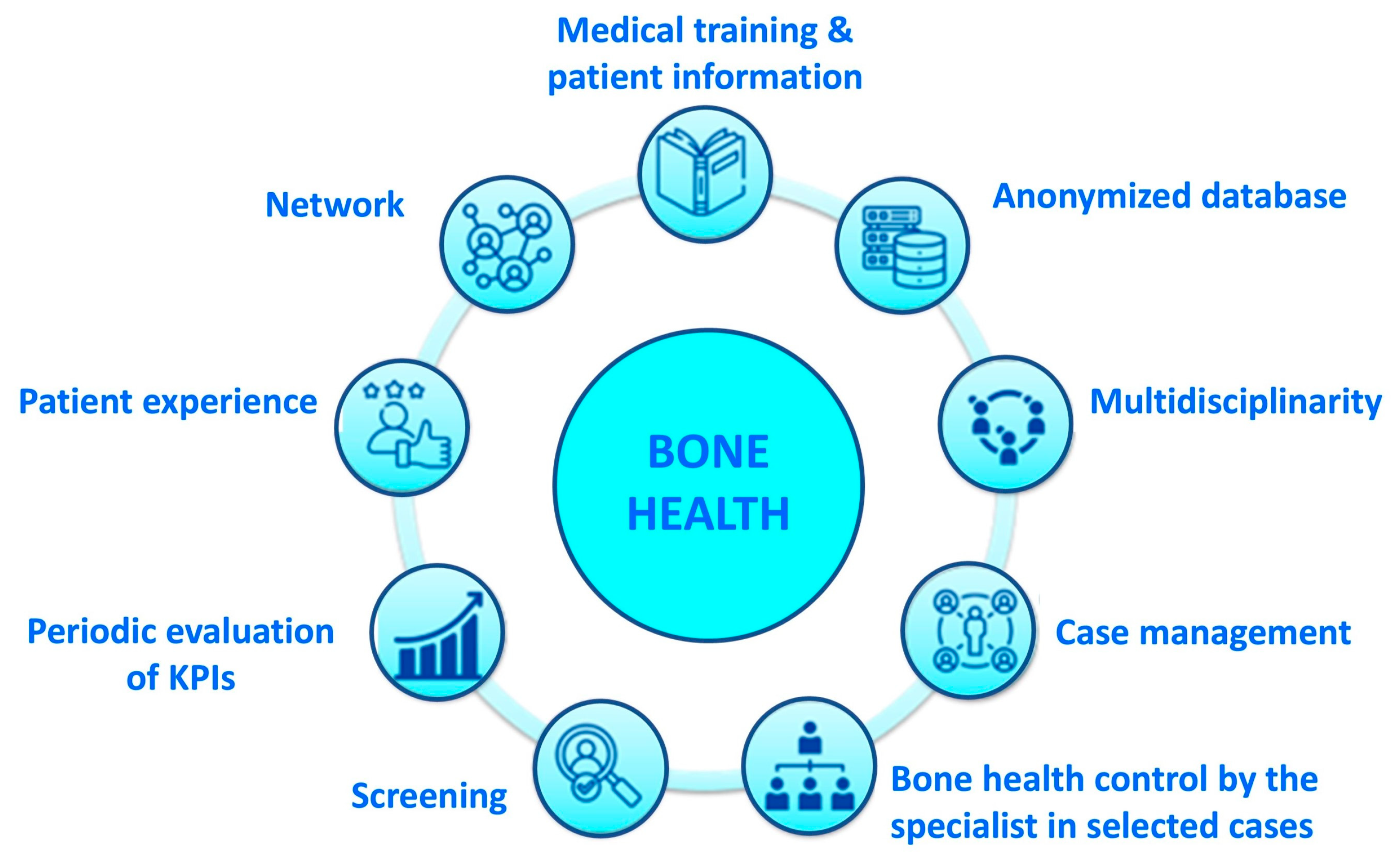

- Presentation and implementation of a bone health management model in every cancer center;

- Assessment at the start and 12 months after the implementation of the project, of two key performance indicators (KPIs);

- Assessment of the rates of bone fractures after five years from implementation of this project in every cancer center.

2.1. Training of Multidisciplinary Team

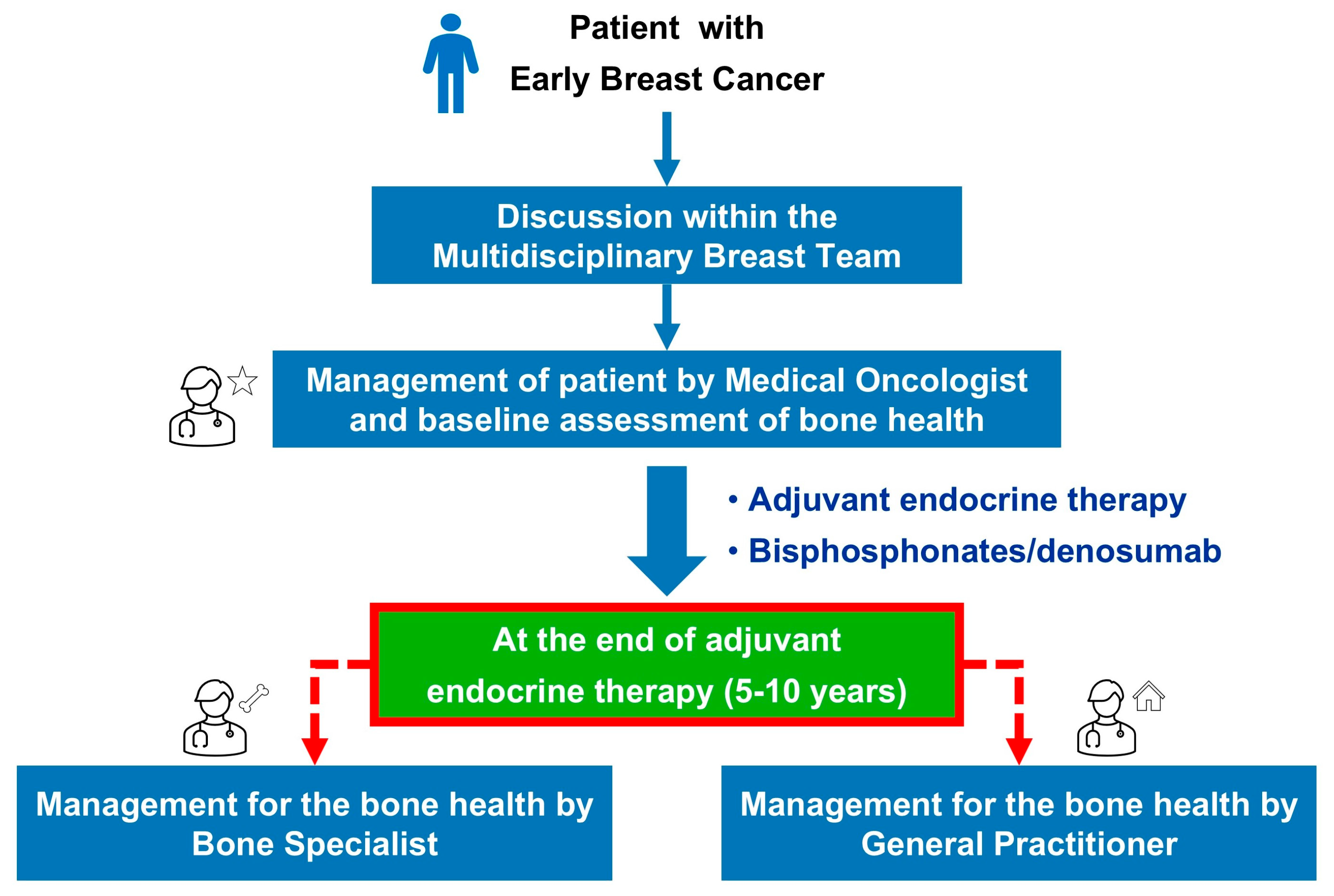

2.2. Presentation and Implementation of a Bone Health Management Model

2.3. Identification and Evaluation of Two Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

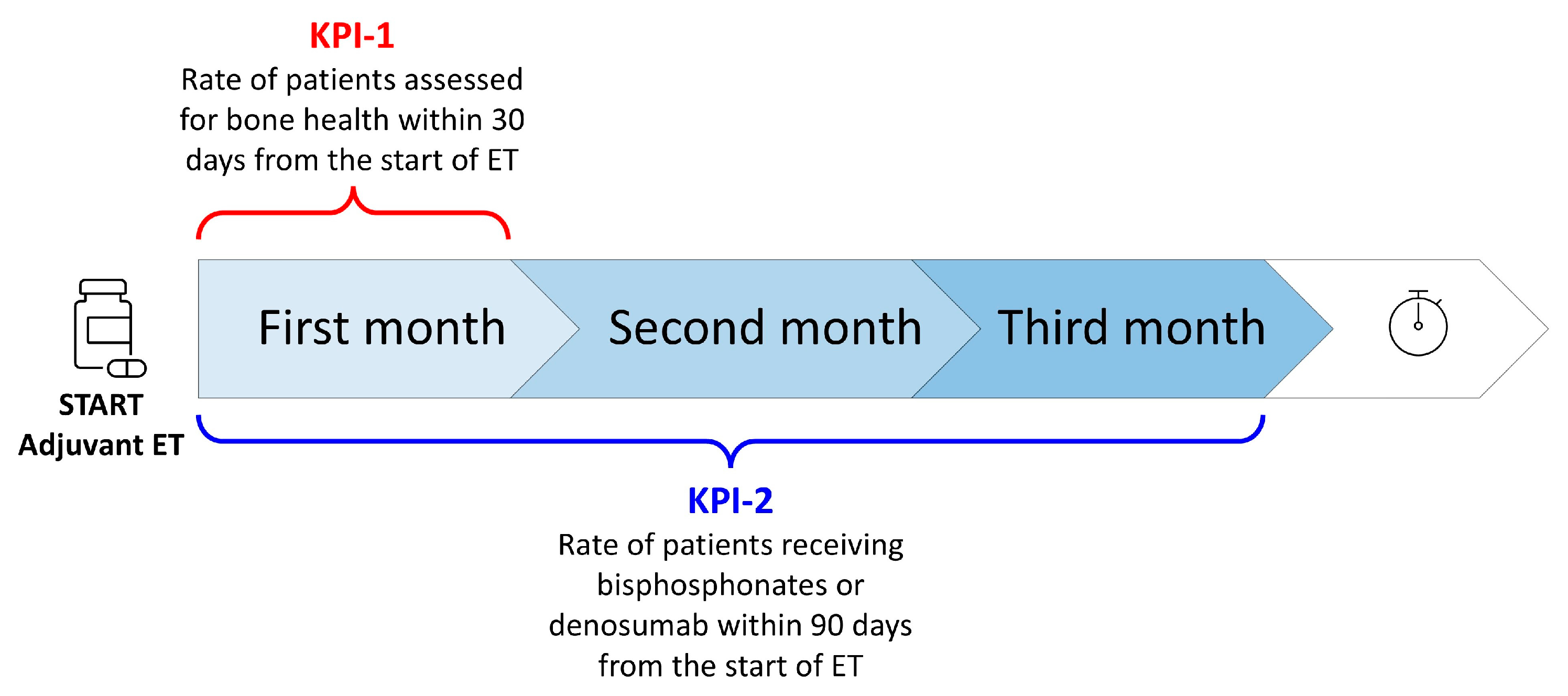

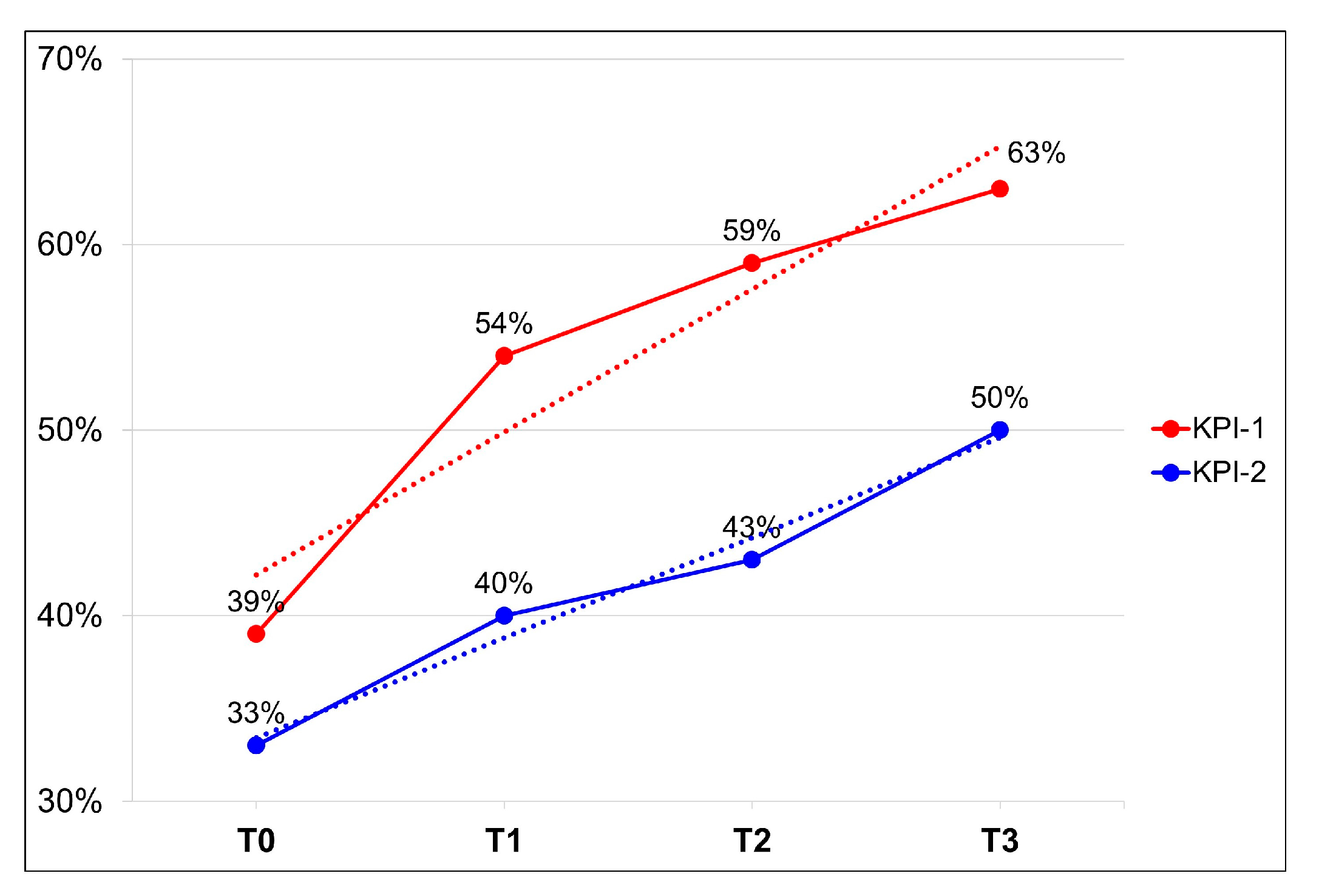

- Key performance indicator no. 1 (KPI-1) was “the rate of HR+ breast cancer patients in postmenopausal status (natural, surgical, secondary to chemotherapy or hormonal blockage) assessed for bone health within 30 days from the start of adjuvant endocrine therapy”;

- Key performance indicator no. 2 (KPI-2) was “the rate of HR+ breast cancer patients receiving bisphosphonates or denosumab within 90 days from the start of adjuvant endocrine therapy” (Figure 3).

- Time T0 refers to a period of 12 months preceding the start of this project;

- Time T1 refers to a period of 3 months after the start of this project;

- Time T2 refers to a period of 6 months from the start of this project;

- Time T3 refers to a period of 12 months from the start of this project.

2.4. Rates of Bone Fractures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breast Cancer Factsheet in 2020 for EU-27 Countries. ECIS—European Cancer Information System. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-12/Breast_cancer_en-Dec_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Fondazione AIOM-AIRTUM-PASSI. I Numeri Del Cancro in Italia 2020. Available online: https://www.fondazioneaiom.it (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Decessi per Tumore e Sesso in Italia Durante l’anno 2017. Dati ISTAT. Available online: https://www.fondazioneaiom.it (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Dafni, U.; Tsourti, Z.; Alatsathianos, I. Breast Cancer Statistics in the European Union: Incidence and Survival across European Countries. Breast Care 2019, 14, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S.; André, F.; Bachelot, T.; Barrios, C.H.; Bergh, J.; Burstein, H.J.; Cardoso, M.J.; Carey, L.A.; Dawood, S.; Del Mastro, L.; et al. Early Breast Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linea Guida AIOM. Carcinoma Mammario in Fase Precoce. 2023. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/linee-guida-aiom-2023-carcinoma-mammario-in-stadio-precoce/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Davies, C.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Clarke, M.; Cutter, D.; Darby, S.; McGale, P.; Pan, H.C.; Taylor, C.; et al.; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Relevance of Breast Cancer Hormone Receptors and Other Factors to the Efficacy of Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Aromatase Inhibitors versus Tamoxifen in Early Breast Cancer: Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of the Randomised Trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.A.; Pagani, O.; Fleming, G.F.; Walley, B.A.; Colleoni, M.; Láng, I.; Gómez, H.L.; Tondini, C.; Ciruelos, E.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Tailoring Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Premenopausal Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, P.A.; Regan, M.M.; Fleming, G.F.; Láng, I.; Ciruelos, E.; Bellet, M.; Bonnefoi, H.R.; Climent, M.A.; Da Prada, G.A.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Adjuvant Ovarian Suppression in Premenopausal Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, K.; Lima Ferreira, J.; Tsourdi, E.; Body, J.-J.; Hadji, P.; Zillikens, M.C. Updated Guidance on the Management of Cancer Treatment-Induced Bone Loss (CTIBL) in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Bone Oncol. 2021, 28, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastell, R.; O’Neill, T.W.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Langdahl, B.; Reid, I.R.; Gold, D.T.; Cummings, S.R. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.J.; Hickish, T.; Kanis, J.A.; Tidy, A.; Ashley, S. Effect of Tamoxifen on Bone Mineral Density Measured by Dual-Energy x-Ray Absorptiometry in Healthy Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996, 14, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Mlineritsch, B.; Luschin-Ebengreuth, G.; Kainberger, F.; Kässmann, H.; Piswanger-Sölkner, J.C.; Seifert, M.; Ploner, F.; Menzel, C.; Dubsky, P.; et al. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy plus Zoledronic Acid in Premenopausal Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: 5-Year Follow-up of the ABCSG-12 Bone-Mineral Density Substudy. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchand, S.K.; Cheung, Y.-M.; Yeo, B.; Grossmann, M. The Effects of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy on Bone Health in Women with Breast Cancer. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 241, R111–R124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaglio, M.; Sun, Z.; Price, K.N.; Castiglione-Gertsch, M.; Hawle, H.; Thürlimann, B.; Mouridsen, H.; Campone, M.; Forbes, J.F.; Paridaens, R.J.; et al. Bone Fractures among Postmenopausal Patients with Endocrine-Responsive Early Breast Cancer Treated with 5 Years of Letrozole or Tamoxifen in the BIG 1-98 Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.; Cuzick, J.; Baum, M.; Buzdar, A.; Dowsett, M.; Forbes, J.F.; Hoctin-Boes, G.; Houghton, J.; Locker, G.Y.; Tobias, J.S.; et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) Trial after Completion of 5 Years’ Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer. Lancet 2005, 365, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, E.; Seruga, B.; Niraula, S.; Carlsson, L.; Ocaña, A. Toxicity of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, O.L.; Spinelli, J.J.; Gotay, C.C.; Ho, W.Y.; McBride, M.L.; Dawes, M.G. Aromatase Inhibitors Are Associated with a Higher Fracture Risk than Tamoxifen: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2018, 10, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldvaser, H.; Barnes, T.A.; Šeruga, B.; Cescon, D.W.; Ocaña, A.; Ribnikar, D.; Amir, E. Toxicity of Extended Adjuvant Therapy with Aromatase Inhibitors in Early Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersini, R.; Monteverdi, S.; Mazziotti, G.; Amoroso, V.; Roca, E.; Maffezzoni, F.; Vassalli, L.; Rodella, F.; Formenti, A.M.; Frara, S.; et al. Morphometric Vertebral Fractures in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Bone 2017, 97, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sire, A.; Lippi, L.; Venetis, K.; Morganti, S.; Sajjadi, E.; Curci, C.; Ammendolia, A.; Criscitiello, C.; Fusco, N.; Invernizzi, M. Efficacy of Antiresorptive Drugs on Bone Mineral Density in Post-Menopausal Women With Early Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitors: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 829875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.; Hadji, P.; Body, J.-J.; Santini, D.; Chow, E.; Terpos, E.; Oudard, S.; Bruland, Ø.; Flamen, P.; Kurth, A.; et al. Bone Health in Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1650–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, F.; Gallo, C.; Lastoria, S.; Di Maio, M.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Gravina, A.; Landi, G.; Rossi, E.; Pacilio, C.; Labonia, V.; et al. Bone Effect of Adjuvant Tamoxifen, Letrozole or Letrozole plus Zoledronic Acid in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: The Randomized Phase 3 HOBOE Study. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2027–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Bell, R.; Hinsley, S.; Marshall, H.; Brown, J.; Cameron, D.; Dodwell, D.; Coleman, R. Adjuvant Zoledronic Acid Reduces Fractures in Breast Cancer Patients; an AZURE (BIG 01/04) Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 94, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brufsky, A.M.; Harker, W.G.; Beck, J.T.; Bosserman, L.; Vogel, C.; Seidler, C.; Jin, L.; Warsi, G.; Argonza-Aviles, E.; Hohneker, J.; et al. Final 5-Year Results of Z-FAST Trial: Adjuvant Zoledronic Acid Maintains Bone Mass in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Letrozole. Cancer 2012, 118, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart, A.; Frassoldati, A.; Paija, O.; Sleeboom, H.P.; Jerusalem, G.; Mebis, J.; Deleu, I.; Miller, J.; Schenk, N.; Neven, P. Immediate Administration of Zoledronic Acid Reduces Aromatase Inhibitor-Associated Bone Loss in Postmenopausal Women With Early Breast Cancer: 12-Month Analysis of the E-ZO-FAST Trial. Clin. Breast Cancer 2012, 12, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.; de Boer, R.; Eidtmann, H.; Llombart, A.; Davidson, N.; Neven, P.; von Minckwitz, G.; Sleeboom, H.P.; Forbes, J.; Barrios, C.; et al. Zoledronic Acid (Zoledronate) for Postmenopausal Women with Early Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Letrozole (ZO-FAST Study): Final 60-Month Results. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Adjuvant Bisphosphonate Treatment in Early Breast Cancer: Meta-Analyses of Individual Patient Data from Randomised Trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Pfeiler, G.; Dubsky, P.C.; Hubalek, M.; Greil, R.; Jakesz, R.; Wette, V.; Balic, M.; Haslbauer, F.; Melbinger, E.; et al. Adjuvant Denosumab in Breast Cancer (ABCSG-18): A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linee Guida AIOM. Neoplasie Della Mammella. Edizione 2020. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020_LG_AIOM_NeoplasieMammella.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Linea Guida AIOM. Metastasi Ossee e Salute Dell’osso. 2024. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/linee-guida-aiom-2024-metastasi-ossee-e-salute-dellosso/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Determina AIFA Del 14 Maggio 2015. Modifiche Alla Nota 79 Di Cui Alla Determinazione Del 7 Giugno 2011. (Determina n. 589/2015). (15A03762) (GU n.115 Del 20-5-2015). Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1728074/determina_14-05-2015_nota79.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Biganzoli, L.; Marotti, L.; Cardoso, M.J.; Cataliotti, L.; Curigliano, G.; Cuzick, J.; Goldhirsch, A.; Leidenius, M.; Mansel, R.; Markopoulos, C.; et al. European Guidelines on the Organisation of Breast Centres and Voluntary Certification Processes. Breast Care 2019, 14, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauley, J.A. Public Health Impact of Osteoporosis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Tamimi, F.; Molto, C.; Di Iorio, M.; Amir, E. Benefit of Adjuvant Bisphosphonates in Early Breast Cancer Treated with Contemporary Systemic Therapy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Volta, A.; Caramella, I.; Di Mauro, P.; Bergamini, M.; Cosentini, D.; Valcamonico, F.; Cappelli, C.; Laganà, M.; Di Meo, N.; Farina, D.; et al. Role of Body Composition in the Prediction of Skeletal Fragility Induced by Hormone Deprivation Therapies in Cancer Patients. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cancer Centers | KPI-1 | KPI-2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time: | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria, Negrar | 0% | 96% | 96% | 74% | 0% | 46% | 46% | 67% | |

| Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia | 12% | 43% | 50% | 62% | 1% | 8% | 13% | 18% | |

| ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo | 0% | 98% | 90% | 88% | 61% | 98% | 67% | 69% | |

| Centro Riferimento Oncologico IRCCS, Aviano | 0% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 3% | 8% | 10% | 8% | |

| AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin | 13% | 25% | 31% | 38% | 45% | 50% | 50% | 56% | |

| Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS, Rome | 35% | 43% | 47% | 60% | 14% | 18% | 24% | 39% | |

| AOU Ospedali Riuniti, Ancona | 95% | 92% | 82% | 76% | 95% | 90% | 83% | 79% | |

| IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 47% | 40% | 33% | 38% | |

| Azienda Ospedaliera Cardarelli, Naples | 100% | 89% | 96% | 98% | 75% | 89% | 96% | 98% | |

| Total | 39% | 54% | 59% | 63% | 33% | 40% | 43% | 50% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gori, S.; Fabi, A.; Berardi, R.; Villa, P.; Zaniboni, A.; Prochilo, T.; Bighin, C.; Del Conte, A.; Riccardi, F.; Airoldi, M.; et al. A New Model for Bone Health Management in Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy—The Predict & Prevent Project. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243292

Gori S, Fabi A, Berardi R, Villa P, Zaniboni A, Prochilo T, Bighin C, Del Conte A, Riccardi F, Airoldi M, et al. A New Model for Bone Health Management in Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy—The Predict & Prevent Project. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243292

Chicago/Turabian StyleGori, Stefania, Alessandra Fabi, Rossana Berardi, Paola Villa, Alberto Zaniboni, Tiziana Prochilo, Claudia Bighin, Alessandro Del Conte, Ferdinando Riccardi, Mario Airoldi, and et al. 2025. "A New Model for Bone Health Management in Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy—The Predict & Prevent Project" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243292

APA StyleGori, S., Fabi, A., Berardi, R., Villa, P., Zaniboni, A., Prochilo, T., Bighin, C., Del Conte, A., Riccardi, F., Airoldi, M., Chirco, A., Cinieri, S., Orlandi, A., Assanti, M., Valerio, M., Tessari, R., Mantoan, C., Verzè, M., Puglisi, F., & Nicolis, F. (2025). A New Model for Bone Health Management in Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy—The Predict & Prevent Project. Healthcare, 13(24), 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243292