3. Results

The study included 310 pregnant women, with a mean age of 31 years (range: 16–44). Among the 308 respondents who reported their age, 63 women (20.4%) were over 34 years old. Most participants had higher education (174 women, 56.9%), followed by secondary education (114 women, 37.3%) and primary education (17 women, 5.6%). A total of 273 women (88.1%) were professionally active, including 35 (12.8%) employed in healthcare-related fields. Regarding place of residence, 119 women (39.0%) lived in rural areas, 99 (32.5%) in small towns (up to 150,000 inhabitants), and 87 (28.5%) in large cities. For 124 women (40.3%), this was their first delivery; 122 (39.6%) had their second, and 62 (20.1%) had given birth three or more times. A history of one miscarriage was reported by 16.1% of respondents, while 8.1% had experienced two or more. Most women (278, 89.7%) delivered at term (≥37 weeks), whereas 32 (10.3%) had preterm deliveries. In terms of delivery mode, 184 women (59.4%) had vaginal births, and 126 (40.6%) underwent cesarean sections. The most common indications for cesarean section were fetal distress (28 patients, 22.3%), macrosomia and lack of labor progress (both 19 patients, 15.1%), and abnormal fetal position (15 women, 11.9%) (

Table 1).

Among the newborns, 298 (97.1%) were genetically healthy and free of developmental defects. Nine infants (2.9%) presented health issues, including six (2.0%) with congenital anomalies. No genetic disorders were diagnosed. Reported anomalies included cardiovascular defects in four cases and urinary tract malformations in three, with one infant exhibiting both cardiac and urinary system defects. Half of these anomalies (three cases) were detected prenatally, while the remaining were diagnosed postnatally.

In the study group, 193 women (62.5%) experienced uncomplicated pregnancies. Among the 116 women (37.5%) with complications, the most frequently reported conditions were diabetes (39 women, 12.9%), thyroid disorders and infections (both 38 women, 12.6%), and hypertension (21 women, 7.0%).

Regarding knowledge assessment, 220 respondents (71.0%) correctly identified tests that detect developmental defects. The detailed distribution of responses is presented in

Table 2.

A correct response to the question “

what tests detect genetic disorders in the fetus?” was provided by 230 women (74.2%). The detailed distribution of responses is presented in

Table 3.

A correct number of recommended ultrasound examinations during pregnancy was indicated by 158 women (51.0%). An incorrect number was provided by 152 women (49.0%), of whom 70 (46.1%) expressed confidence in their knowledge. Regarding the timing of subsequent ultrasound examinations, 94 women (30.3%) correctly identified the recommended timeframe for the first examination, 118 (38.2%) for the second, and 82 respondents (26.5%) for the third.

The actual number of ultrasounds performed during the most recent pregnancy was reported by 216 women. Among them, 138 patients (64.9%) stated that ultrasound was performed at every visit, although not all respondents specified the exact number of visits. On average, 5.8 ± 5.3 examinations were performed, with a median of 6 (range: 0–30). Three or more examinations were conducted for 178 patients (57.4%).

First-trimester ultrasound within the recommended timeframe was reported by 205 women (66.1%), second-trimester by 198 (63.9%), and third-trimester by 198 (63.9%).

Information regarding the timing of ultrasound examinations primarily came from the attending physician performing the scan (205 women, 66.1%) or from the referring physician (58 women, 19.7%). Overall, physicians were the main source of knowledge for 263 respondents (85.8%). Only 3 women (1.0%) reported receiving this information from a midwife or other medical staff. The remaining participants obtained information from family and friends, the Internet, or other sources (

Table 4).

The range of conditions detectable by the first-trimester combined test was correctly identified by 198 women (63.9%). A correct set of examinations included in the combined test was reported by 127 women (41.0%). One hundred forty-five women (46.8%) accurately indicated the gestational period during which this test is performed; however, only 36 women (11.7%) correctly identified which women should undergo the test. As an indication for the test, maternal age over 34 years was reported by 112 women (36.1%), while another age threshold was indicated by 31 women (10.0%). A genetic history was noted by 102 women (32.9%).

Among respondents, 134 women (48.6%) underwent the first-trimester combined test. It was not specified whether the test was performed under the state-funded Prenatal Testing Program or privately. Of the women aged over 34 years, 37 (58.7%) underwent the test, compared to 97 respondents (38.5%) in the younger group. Among those who underwent the combined test, 64 women (56.6%) correctly identified the indication for the test.

As a source of knowledge influencing the decision to undergo the combined test, 130 respondents (97.0%) indicated a physician, while one patient (0.7%) cited a midwife or other medical staff, one (0.7%) mentioned family or friends, and another referred to scientific publications or other sources.

In the entire study population, 73 respondents (23.6%) indicated the physician who performed the test as a source of knowledge about the combined test, while 98 women (31.6%) cited the referring physician. Four patients indicated both responses. In total, 167 women (53.9%) identified a physician as their source of knowledge. Information obtained from a midwife or another staff member was cited by 10 patients (3.2%), from family or friends by 10 (3.2%), from the Internet by 17 (5.5%), and from other sources by 4 pregnant women (1.3%).

Regarding NIPT, 189 women (61.2%) stated that they did not know which conditions the test detects. Among those declaring knowledge, 106 women (87.6%) provided correct answers, and 86 (27.8%) correctly described the method of examination (blood draw). Ninety-four respondents (30.3%) incorrectly stated that ultrasound is included in NIPT, and 14 women (4.5%) indicated amniotic fluid testing.

One hundred forty-five women (46.8%) claimed to know when NIPT is best performed, but only 87 (28.1%) correctly specified the timing. Correct indications for NIPT were mentioned by 109 patients (35.2%). No respondent indicated high risk of chromosomal aberrations as an indication for NIPT; maternal age over 34 years was reported by 50 respondents (16.1%), another age threshold by 7 patients (2.3%), and a referral from the attending physician by 3 women (1.0%). Additionally, 5 respondents (1.6%) cited family history.

A total of 251 respondents answered whether they underwent NIPT during pregnancy. Of these, 29 women reported having the test. Among them, 13 (44.8%) were classified as having increased risk of chromosomal aberrations (one due to combined test results, others due to age ≥ 35 years). The percentage of patients under 35 who underwent NIPT was 8.7% (17 out of 195), while among those aged 35 and older, it was 22.2% (12 out of 54).

The referring physician was the source of knowledge about NIPT for 50 women (16.1%), while the physician performing the test was cited by 51 women (16.5%), totaling 99 women (31.9%) who identified a physician as their source. A midwife or other medical staff served as a source for 6 women (1.9%), family and friends for 18 women (5.8%), the Internet for 11 (3.5%), and other sources for 6 women (1.9%).

Knowledge regarding conditions detected after amniocentesis was reported by 135 respondents (43.5%). The most commonly indicated condition was trisomy 21, noted by 63 women (20.5%), followed by trisomy 18 (34 women, 11.0%) and trisomy 20 (13 women, 6.5%). The gestational age at which amniocentesis is recommended was correctly identified by 77 women (24.9%). A total of 195 women (62.9%) stated that they did not know the indications for amniocentesis. Correct indications were identified by 105 women (34.0%). Increased risk of chromosomal aberrations was noted as an indication by 62 respondents (20.0%), abnormal ultrasound findings by 39 women (12.6%), and advanced maternal age by 45 women (14.5%).

In the studied group, 5 women (1.8%) underwent amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling during pregnancy. Due to the small size of this group, no further analysis was conducted.

In the next stage, respondents were categorized by knowledge level: high, medium, and low. The maximum score was 16 points. A low level of knowledge was assigned to 131 patients scoring below 4 points, medium to 139 women scoring 4–7 points, and high to 51 respondents scoring above 8 points. Statistical analysis revealed no significant correlation between age group (<34 years vs. ≥34 years) and knowledge level (linear correlation test,

p = 0.434). Data are presented in

Table 5.

Considering the education level of respondents, individuals with primary education demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of low knowledge regarding prenatal testing compared to women with secondary or higher education. Conversely, the highest knowledge levels were observed among women with higher education. A statistically significant association between education level and knowledge about prenatal testing was confirmed (linear correlation test,

p < 0.001). The data are presented in

Table 6.

The relationship between knowledge level regarding prenatal tests and employment in healthcare was analyzed. Statistical testing did not confirm a significant association (linear correlation test,

p = 0.073). The data are presented in

Table 7.

The level of knowledge among women living in rural areas, small towns, medium-sized towns, and large cities was analyzed. Knowledge level increased with the population size of the locality, with the highest scores observed among women residing in large cities. A statistically significant association between place of residence and knowledge level was confirmed (linear correlation test,

p = 0.001). The data are presented in

Table 8.

The impact of the number of pregnancies (births and miscarriages) on knowledge level was analyzed. Women giving birth for the first time exhibited the highest level of knowledge, while knowledge decreased with the number of births. A statistically significant association between parity and knowledge level was confirmed (linear correlation test,

p = 0.013). The data are presented in

Table 9.

The impact of a history of miscarriage on knowledge level was analyzed. Statistical testing did not confirm a significant association (linear correlation test,

p = 0.063). The data are presented in

Table 10.

The impact of pregnancy complications on knowledge level was analyzed. Statistical testing did not confirm a significant association (linear correlation test,

p = 0.100). The data are presented in

Table 11.

It is particularly noteworthy that no correlation was found between the level of knowledge about prenatal tests and having previously given birth to a child with a congenital defect (linear correlation test,

p = 0.665). The data are presented in

Table 12.

Another aspect analyzed was the level of knowledge about prenatal tests among patients who underwent ultrasound examinations during pregnancy in accordance with recommended guidelines. This group included 198 women who had ultrasound examinations performed as advised. As anticipated by the authors, women who adhered to the recommended ultrasound schedule demonstrated a significantly higher level of knowledge (linear correlation test, p < 0.001).

In the multiple regression model, significant predictors of knowledge level included the number of previous pregnancies, place of residence, and level of education (

Table 13).

When narrowing the multiple regression model to five significant factors—maternal age, number of previous pregnancies, mode of delivery, place of residence, and level of education—the results remained consistent. The strongest predictor of knowledge level was education, followed by place of residence and number of previous pregnancies. Maternal age and mode of delivery were not statistically significant. The data are presented in

Table 14.

In the logistic regression analysis assessing awareness of prenatal testing (aware vs. unaware), the final model retained three predictors: maternal age, place of residence, and level of education. Level of education demonstrated the strongest association with awareness, followed by place of residence. Maternal age showed a weaker effect and was not statistically significant. The results are presented in

Table 15.

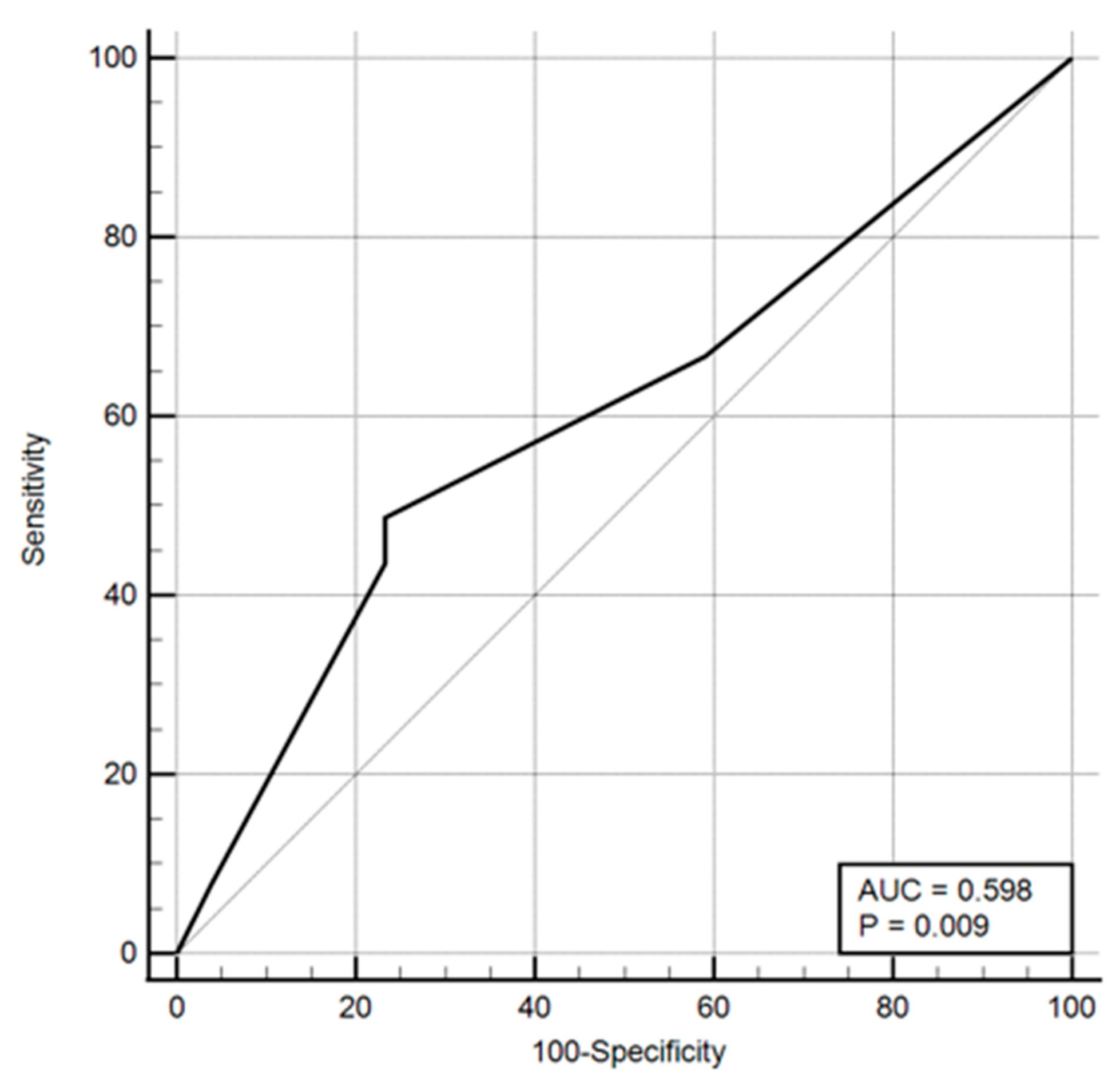

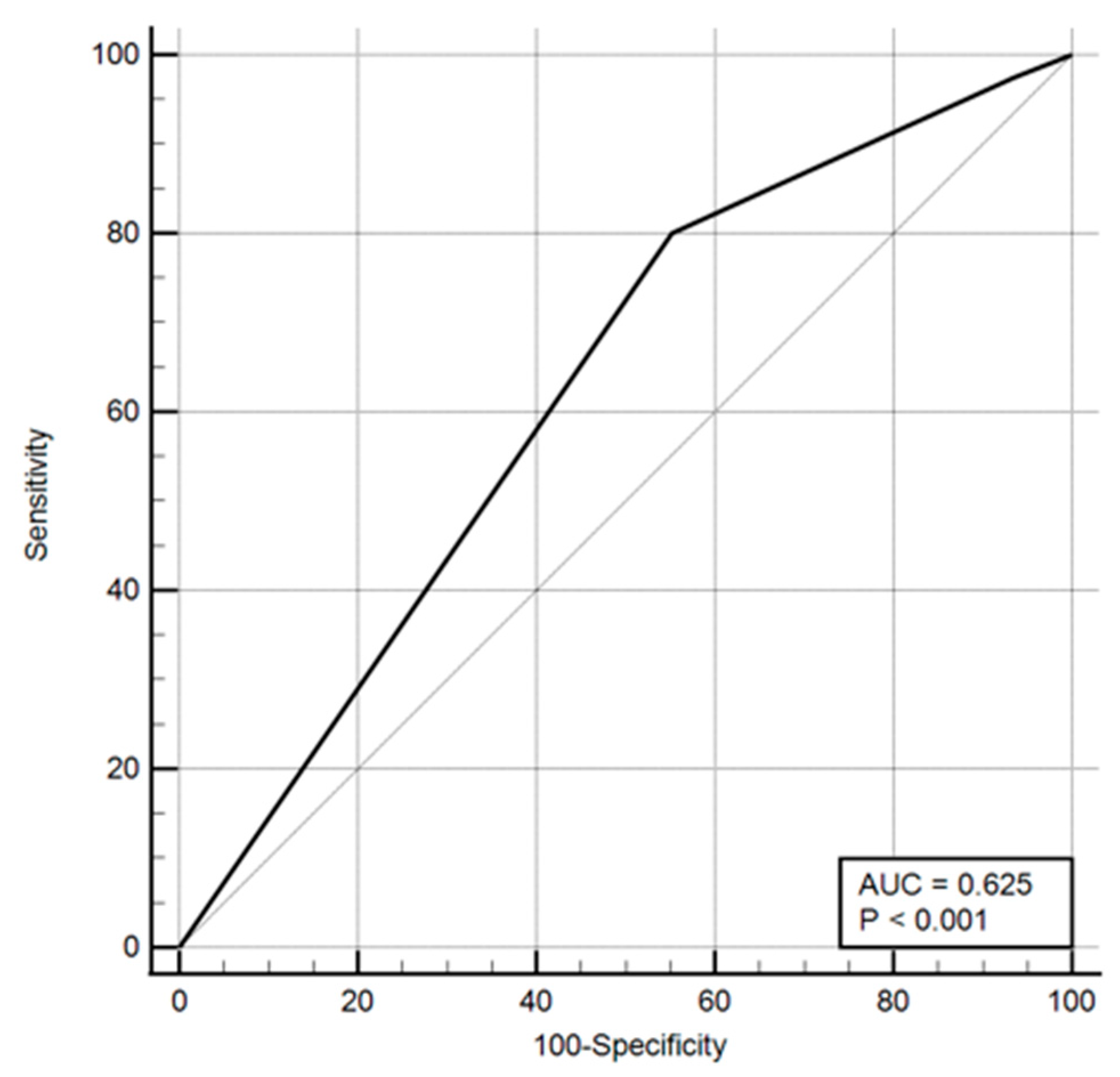

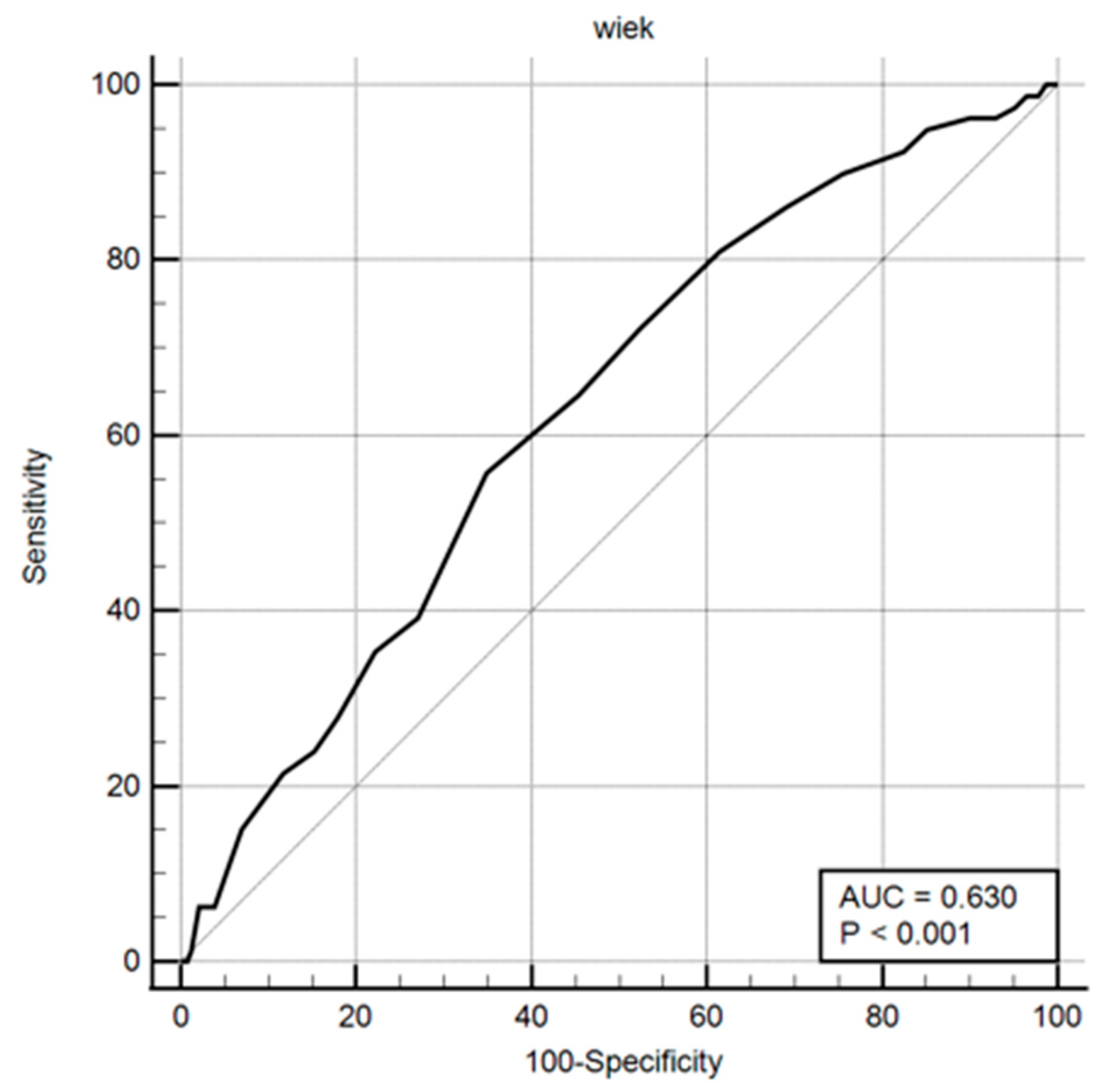

Odds ratios and ROC curves were computed for these parameters, with the results presented in both tabular and graphical formats (

Table 16,

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Patients who correctly identified the recommended number of ultrasound examinations during pregnancy were significantly more likely to have undergone these examinations in accordance with clinical guidelines (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.006). However, no significant difference was observed in knowledge regarding the appropriate gestational periods for first- and second-trimester ultrasounds between women who adhered to the standards and those who did not (Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.90 for first trimester; p = 0.553 for second trimester). In contrast, knowledge of the recommended timing for the third-trimester ultrasound reached statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.05), indicating that patients who correctly completed all ultrasound examinations were more likely to know when this examination should be performed.

The analysis also examined whether women who underwent the combined test demonstrated greater knowledge of prenatal screening compared to those who did not. A strong association was confirmed (linear correlation test, p < 0.001). Among the 134 respondents who completed the combined test, knowledge of its individual components was significantly higher: conditions detected (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001), test components (p < 0.001), and recommended timing (p < 0.001).

A similar pattern was observed for non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). Both overall knowledge (linear correlation test, p < 0.001) and specific knowledge—conditions detected (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001), test components (p < 0.001), timing and indications (p < 0.001)—were significantly higher among the 29 women who underwent NIPT compared to other respondents.

Conversely, the performance of amniocentesis was not associated with overall knowledge of prenatal testing (linear correlation test, p = 0.791), nor with knowledge of conditions diagnosed through invasive testing (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.372) or appropriate timing and indications (p = 1.000). These findings should be interpreted with caution, as amniocentesis was performed in only five participants.

The study also assessed whether knowledge levels varied by the source of information. Sources were categorized into three groups: physicians (including primary care and specialists), other medical staff, and non-medical sources. Women who identified physicians as their primary source of information demonstrated significantly better alignment with guidelines regarding the number of ultrasound examinations (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001) and their timing: first trimester (p = 0.004), second trimester (p = 0.002), and third trimester (p = 0.001). No respondents reported other medical personnel as their source of ultrasound-related knowledge.

Similarly, patients informed by physicians correctly identified the conditions detected by the combined test (chi-square test, p < 0.001), its components (p < 0.001), and the appropriate gestational period (p < 0.001). Although the group informed by other medical staff was small (No = 7), these respondents also provided more accurate answers (p < 0.001).

In contrast, the source of information did not significantly influence knowledge regarding NIPT, including conditions detected (chi-square test, p = 0.885), test components (p = 0.749), timing (p = 0.712), or indications (p = 0.223).

4. Discussion

The range of prenatal tests offered to pregnant women depends on several factors. Qualification is typically based on information provided by the physician regarding the type of tests, their scope, and the recommended gestational period for their performance. After receiving this information, the patient decides which tests to undergo. This study aimed to assess whether pregnant women possess sufficient knowledge to make informed decisions about prenatal screening, identify the main sources of this knowledge, and determine which sources are perceived as most reliable. Additionally, the study examined awareness of tests recommended for women at high risk of congenital anomalies.

Survey results revealed that over 70% of respondents were aware that congenital anomalies—both structural and genetic—can be detected through ultrasound examinations. However, only about half correctly identified the recommended number of ultrasound scans and their timing during pregnancy. Analysis of actual practice suggested a tendency toward overuse of ultrasound, with many women reporting scans at nearly every visit, averaging six examinations instead of the recommended minimum of three [

10]. Given that physicians were cited as the primary source of information by over 85% of respondents, these findings raise questions about whether misinformation stems from inadequate communication or from patients’ misunderstanding of indications for additional scans, such as fetal growth restriction or multiple pregnancies.

A similar knowledge gap was observed regarding the combined test. While 63% of respondents correctly identified its purpose, only 11.7% accurately indicated reimbursement criteria according to prevailing guidelines. The most frequently cited indication—maternal age over 34 years—was correctly identified by 36% of respondents. However, this criterion was not exclusive; the combined test was recommended for all pregnant women during the study period, with age serving only as a threshold for reimbursement. Physicians often cited lack of funding as a reason for not recommending the test [

24].

The proportion of women aware of eligibility for the combined test was low, as reflected by the fact that only 48.6% of respondents underwent the test, despite guidelines requiring physicians to inform patients of this option. Among women over 34 years of age—who qualified for reimbursement—63.8% underwent the test. Whether non-participation resulted from insufficient information or personal choice remains unclear. Literature suggests that inadequate or unclear communication is a common reason for declining recommended examinations [

25,

26,

27].

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) remains a relatively new, costly, and less commonly utilized diagnostic method, which contributes to limited patient awareness [

28]. This was reflected in our findings, where respondents demonstrated significantly restricted knowledge about NIPT. Due to its high cost, lack of reimbursement, and limited dissemination of information, NIPT was rarely performed, even among women with clear indications [

24]. Within our study population, women classified as high-risk for genetic disorders—specifically those aged 35 years or older—were nearly three times more likely to undergo NIPT compared to other respondents.

Both the combined test and NIPT were most frequently performed upon physician recommendation, underscoring the critical role of healthcare providers in shaping patient decisions. However, the low uptake of these tests suggests that current guidelines are not being communicated effectively. Alarmingly, women in high-risk groups did not exhibit greater knowledge about prenatal testing than other respondents. Whether this reflects insufficient counseling or unclear communication remains uncertain. Gates highlighted that patients respond more effectively to risk presented as frequency (e.g., 1:100) rather than percentage (1%) [

26], suggesting that risk communication strategies may require refinement. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether women classified as intermediate-risk following the combined test are adequately informed about the availability of non-invasive diagnostic options [

28].

Our study did not assess indications for invasive diagnostics or patient consent for amniocentesis. Previous research emphasizes the importance of how information about invasive procedures is conveyed and its influence on patient decision-making [

29,

30,

31]. Sadłecki et al. similarly noted that accurate communication regarding the benefits and risks of both invasive and non-invasive tests is essential for informed consent [

32].

Interestingly, no correlation was observed between knowledge level and professional involvement in healthcare. This suggests that prenatal testing is either underrepresented or treated superficially in medical education, despite its relevance to individuals who often plan pregnancies shortly after completing their training. Literature confirms that even healthcare professionals engaged in prenatal care frequently lack sufficient knowledge about these tests [

33].

Our analysis did reveal associations between knowledge and factors such as education level, urban residence, and parity. Women with higher education, those living in large cities, and mothers with older children demonstrated greater awareness. Conversely, no correlation was found between knowledge and previous miscarriages, despite expectations that such patients would seek information on genetic and developmental causes of pregnancy loss. Lower educational attainment is consistently cited as a barrier to understanding medical information, highlighting the need for communication strategies tailored to patient comprehension [

34,

35,

36].

Another noteworthy finding was the absence of correlation between knowledge and having a child with a congenital defect, likely due to the small number of such cases in our sample. Overall, adherence to recommended prenatal testing (ultrasound, combined test, NIPT) was significantly higher among women with greater knowledge, reinforcing the importance of patient education [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Given that physicians are the primary source of information, it is imperative that they clearly explain the purpose, timing, and implications of these tests. Our results indicate that physician-provided information about ultrasound and the combined test aligns more closely with current guidelines compared to other sources.

However, the lack of difference in NIPT-related knowledge between patients informed by physicians and those relying on other sources is concerning. This suggests gaps in physician awareness and underscores the need for targeted education. Professional societies have recognized this issue and continue to publish guidelines and resources aimed at improving both provider and patient education [

41].

To address these gaps, we recommend developing an informational brochure summarizing current prenatal testing guidelines. This resource should be distributed during the first prenatal visit, enabling patients to review the information independently and prepare questions for subsequent consultations. Such materials offer objectivity and consistency, reducing variability introduced by individual physician preferences [

42].

Despite advances in patient education and the emergence of digital resources, including podcasts, there remains a lack of accessible, reliable online content explaining prenatal diagnostic options in clear, patient-friendly language. This issue persists globally, not only in Polish-language resources [

43].

Finally, survey-based research carries inherent limitations. In our study, respondents may have consulted external sources such as the Internet while completing the questionnaire. Additionally, women with lower education levels may have been less inclined to participate, potentially introducing selection bias.