Sensitivity and Specificity of Elliptical Modeling and Sagittal Lumbar Alignment Variables in Normal vs. Acute Low Back Pain Patients: Does Pelvic Morphology Explain Group Lordotic Differences?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Data

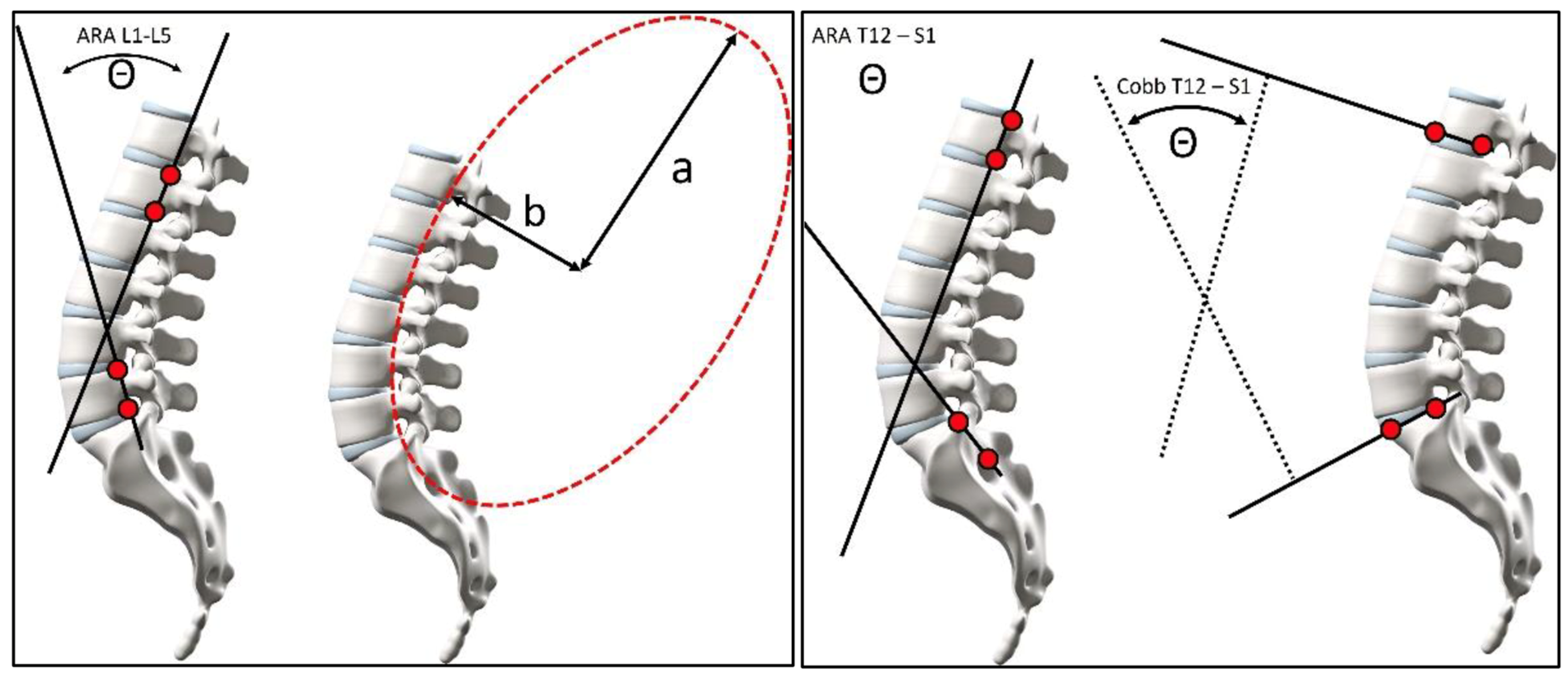

2.2. Lumbar Modeling

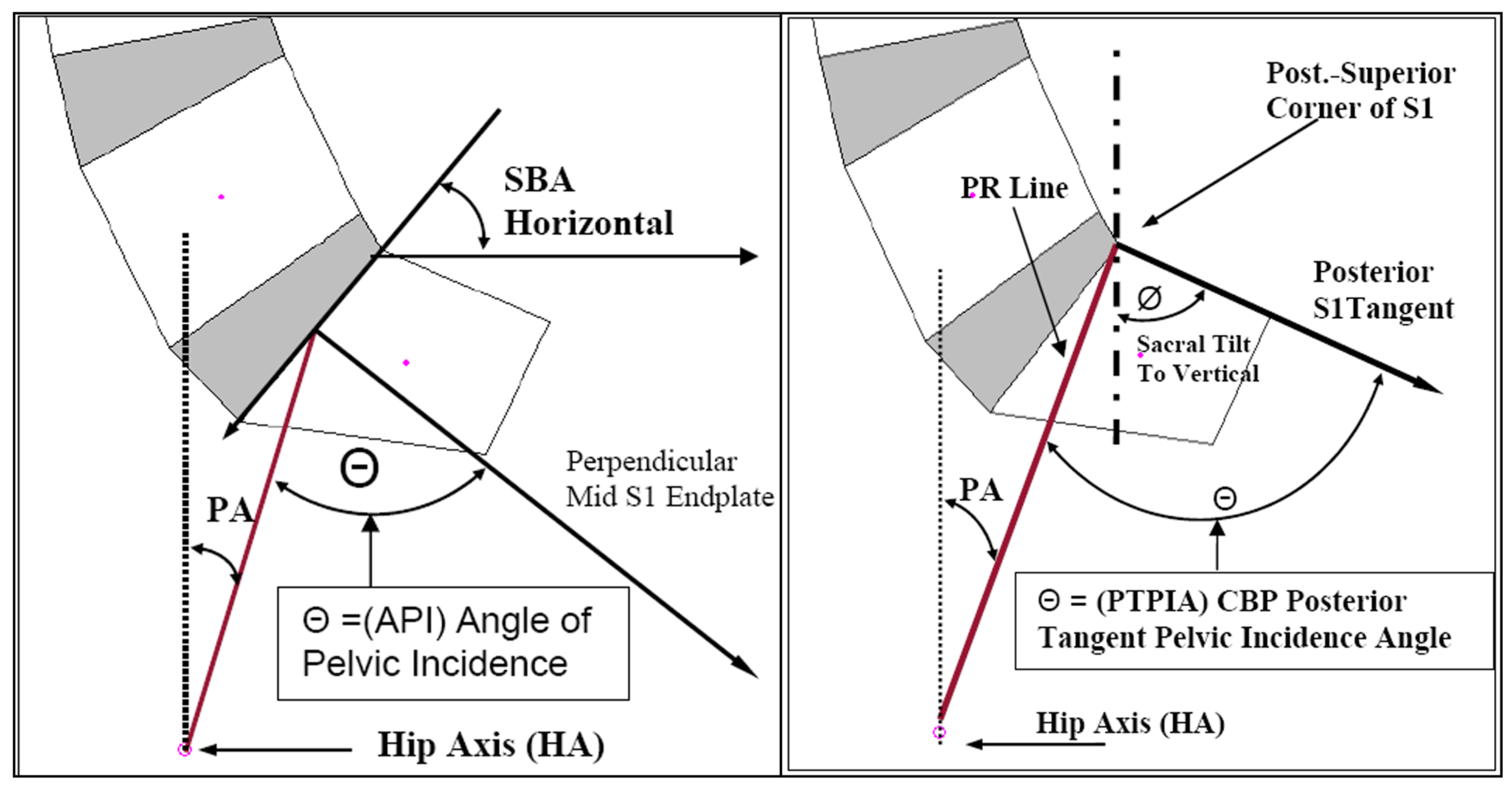

2.3. Radiographic Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

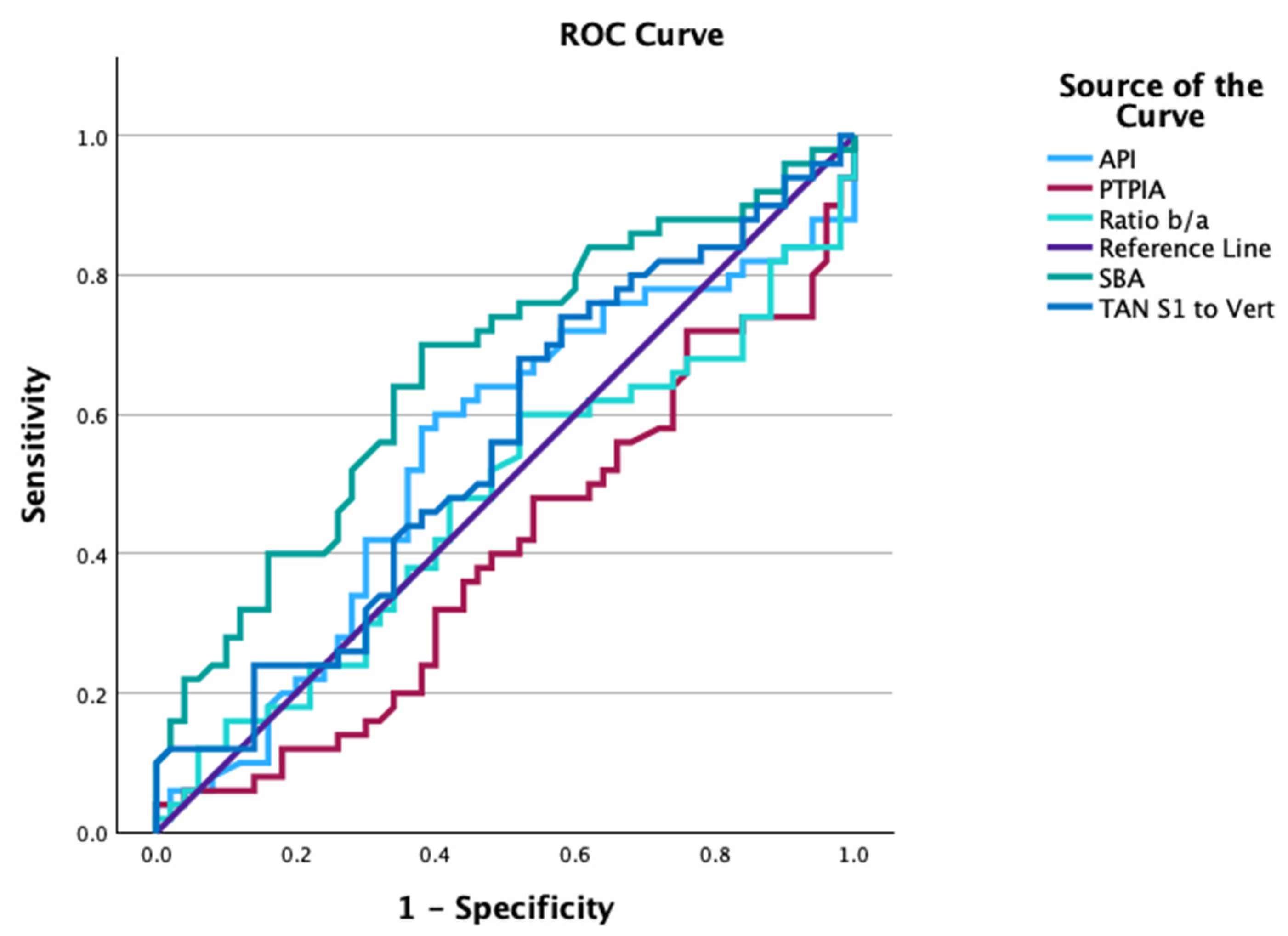

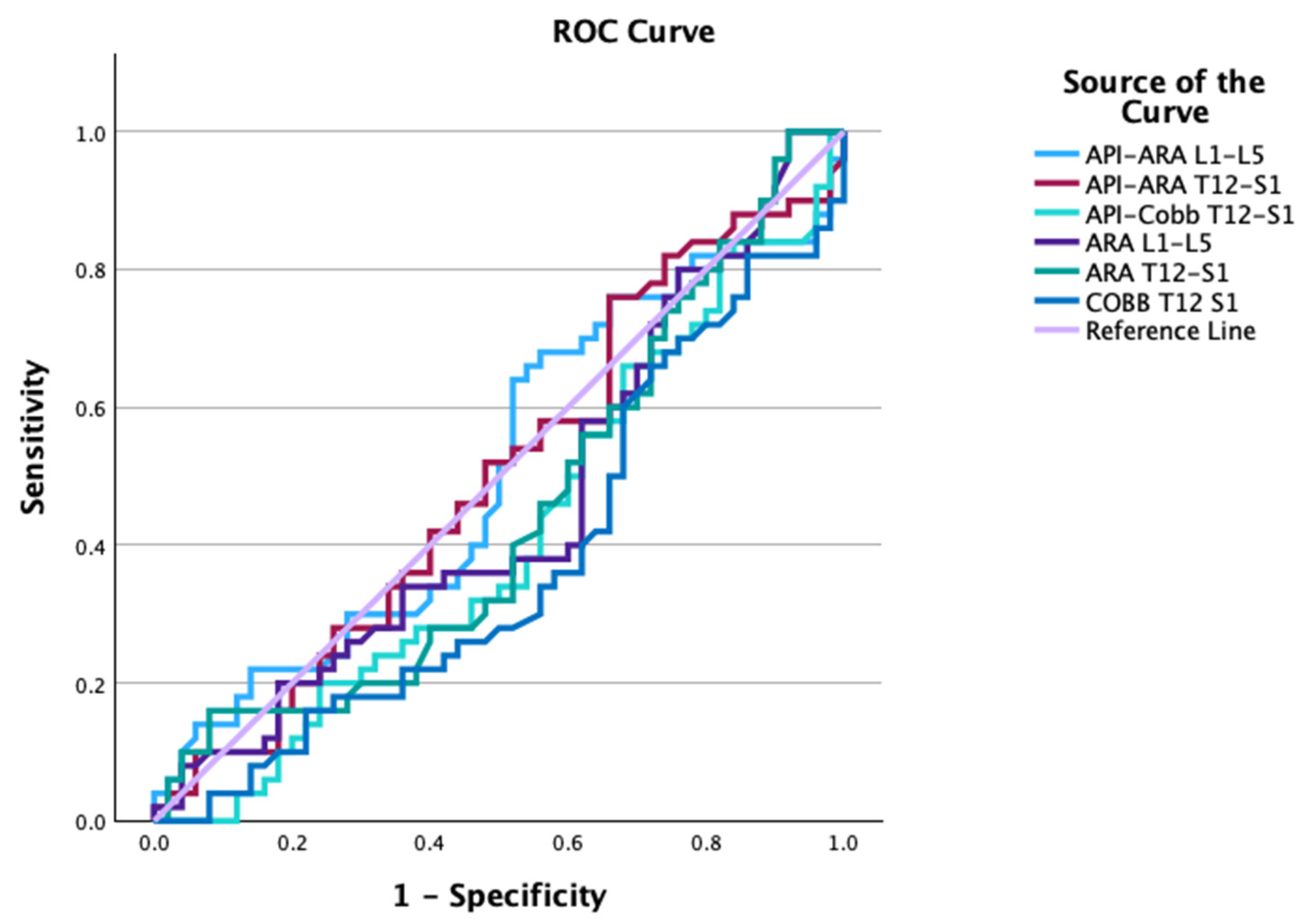

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, S.A.; Prang, T.C.; Meyer, M.R.; Nalley, T.K.; Van Der Merwe, R.; Yelverton, C.; García-Martínez, D.; Russo, G.A.; Ostrofsky, K.R.; Spear, J.; et al. New fossils of Australopithecus sediba reveal a nearly complete lower back. Elife 2021, 10, e70447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagnara, P.; De Mauroy, J.C.; Dran, G.; Gonon, G.P.; Costanzo, G.; Dimnet, J.; Pasquet, A. Reciprocal angulation of vertebral bodies in a sagittal plane: Approach to references for the evaluation of kyphosis and lordosis. Spine 1982, 7, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troyanovich, S.J.; Cailliet, R.; Janik, T.J.; Harrison, D.D.; Harrison, D.E. Radiographic mensuration characteristics of the sagittal lumbar spine from a normal population with a method to synthesize prior studies of lordosis. J. Spinal Disord. 1997, 10, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, G.; Roussouly, P.; Berthonnaud, E.; Dimnet, J. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur. Spine J. 2002, 11, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussouly, P.; Gollogly, S.; Berthonnaud, E.; Dimnet, J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine 2005, 30, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialle, R.; Levassor, N.; Rillardon, L.; Templier, A.; Skalli, W.; Guigui, P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2005, 87, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.D.; Cailliet, R.; Janik, T.J.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Harrison, D.E. Elliptical modeling of the sagittal lumbar lordosis and segmental rotation angles as a method to discriminate between normal and low back pain subjects. J. Spinal Disord. 1998, 11, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, D.W., Jr.; Kilkelly, F.X.; McHale, K.A.; Asplund, L.M.; Mulligan, M.; Chang, A.S. Measurement of lumbar lordosis. Evaluation of intraobserver, interobserver, and technique variability. Spine 1996, 21, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, G. Lumbar lordosis morphology correlates to pelvic incidence and erector spinae muscularity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Haas, J.W.; Moustafa, I.M.; Betz, J.W.; Oakley, P.A. Can the mismatch of measured pelvic morphology vs. lumbar lordosis predict chronic low back pain patients? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushcha, A.O.; Sharif, S.; Zileli, M.; Oertel, J.; Zygourakis, C.C.; Yusupova, A.R. Acute back pain: Clinical and radiologic diagnosis: WFNS spine committee recommendations. World Neurosurg. X 2024, 22, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Fu, R.; Carrino, J.A.; Deyo, R.A. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, D.; Fielding, K.; Bentley, E.; Kerslake, R.; Miller, P.; Pringle, M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001, 322, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, S.; Hilton, S.; Dundas, D.; Rink, E.; Oakeshott, P. Radiography for low back pain: A randomised controlled trial and observational study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2002, 52, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Bussières, A.E.; Taylor, J.A.; Peterson, C. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults-an evidence-based approach-part 3: Spinal disorders. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2008, 31, 33–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, H.J.; Downie, A.S.; Moore, C.S.; French, S.D. Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: A narrative review. Chiropr. Man. Therap. 2018, 26, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, M.; Cancelliere, C.; Mior, S.; Kumar, V.; Smith, A.; Côté, P. The clinical utility of routine spinal radiographs by chiropractors: A rapid review of the literature. Chiropr. Man. Therap. 2020, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Radiophobic fear-mongering, misappropriation of medical references and dismissing relevant data forms the false stance for advocating against the use of routine and repeat radiography in chiropractic and manual therapy. Dose Response 2021, 19, 1559325820984626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.A.; Sacks, B.; Pennington, C.W.; Welsh, J.S. Dose Optimization to Minimize Radiation Risk for Children Undergoing CT and Nuclear Medicine Imaging Is Misguided and Detrimental. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J. LNT and cancer risk assessment: Its flawed foundations part 1: Radiation and leukemia: Where LNT began. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.A.; Sacks, B.; Greenspan, B.S. No Evidence to support radiation health risks due to low-dose medical imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 570–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J. Cancer risk assessment, its wretched history and what it means for public health. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2024, 21, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.A.; Pennington, C.W.; Sacks, B. Subjecting radiologic imaging to the linear no-threshold hypothesis: A non sequitur of non-trivial proportion. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttler, J.M. Application of low doses of ionizing radiation in medical therapies. Dose Response 2020, 18, 1559325819895739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, A.; Williams, C.M.; Henschke, N.; Hancock, M.J.; Ostelo, R.W.; de Vet, H.C.; Macaskill, P.; Irwig, L.; van Tulder, M.W.; Koes, B.W.; et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: Systematic review. BMJ 2013, 347, f7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Radiogenic cancer risks from chiropractic X-rays are zero: 10 reasons to take routine radiographs in clinical practice. Ann. Vert. Sublux. Res. 2018, 10, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Janik, T.J.; Harrison, D.D.; Cailliet, R.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Harrison, D.E. Can the sagittal lumbar curvature be closely approximated by an ellipse? J. Orthop. Res. 1998, 16, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Modi, H.N.; Suh, S.W.; Hong, J.Y.; Park, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Yang, J.H. Reliability of lumbar lordosis measurement in patients with spondylolisthesis: A case-control study comparing the Cobb, centroid, and posterior tangent methods. Spine 2010, 35, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthonnaud, E.; Labelle, H.; Roussouly, P.; Grimard, G.; Vaz, G.; Dimnet, J. A variability study of computerized sagittal spinopelvic radiologic measurements of trunk balance. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2005, 18, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaye, J.; Duval-Beaupère, G.; Hecquet, J.; Marty, C. Pelvic incidence: A fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur. Spine J. 1998, 7, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During, J.; Goudfrooij, H.; Keessen, W.; Beeker, T.W.; Crowe, A. Toward standards for posture. Postural characteristics of the lower back system in normal and pathologic conditions. Spine 1985, 10, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.E. Radiographic and biomechanical analysis of patients with low back pain: A prospective clinical trial. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, New York, NY, USA, 10–14 May 2005; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Diebo, B.G.; Varghese, J.J.; Lafage, R.; Schwab, F.J.; Lafage, V. Sagittal alignment of the spine: What do you need to know? Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2015, 139, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencina, M.J.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Pencina, K.M.; Janssens, A.C.; Greenland, P. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, I.A.; Bevins, T.M.; Lunn, R.A. Back surface curvature and measurement of lumbar spinal motion. Spine 1987, 12, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzün, C.; Yorulmaz, I.; Cindaş, A.; Vatan, S. Low back pain and posture. Clin. Rheumatol. 1999, 18, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, M.; Montella, S.; Salici, F.; Valente, A.; Marchesini, M.; Compagnone, C.; Baciarello, M.; Manferdini, M.E.; Fanelli, G. Mechanisms of low back pain: A guide for diagnosis and therapy. F1000Research 2016, 5, F1000 Faculty Rev-1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.W.; Lim, C.Y.; Kim, K.; Hwang, J.; Chung, S.G. The relationships between low back pain and lumbar lordosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2017, 17, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raastad, J.; Reiman, M.; Coeytaux, R.; Ledbetter, L.; Goode, A.P. The association between lumbar spine radiographic features and low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2015, 44, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, S.G.; Spink, M.J.; Ho, A.; De Jonge, X.J.; Chuter, V.H. Restriction in lateral bending range of motion, lumbar lordosis, and hamstring flexibility predicts the development of low back pain: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reigo, T.; Tropp, H.; Timpka, T. Clinical findings in a population with back pain. Relation to one-year outcome and long-term sick leave. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2000, 18, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, E.L.; Luger, E.; Arbel, R.; Menachem, A.; Dekel, S. A comparative roentgenographic analysis of the lumbar spine in male army recruits with and without lower back pain. Clin. Radiol. 2003, 58, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, O.C. An analytical survey of structural aberrations observed in static radiographic examinations among acute low back cases. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1988, 11, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, D. The role of radiography in primary care patients with low back pain of at least 6 weeks duration: A randomized (unblinded) controlled trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2001, 5, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke, N.; Maher, C.G.; Refshauge, K.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Cumming, R.G.; Bleasel, J.; York, J.; Das, A.; McAuley, J.H. Characteristics of patients with acute low back pain presenting to primary care in Australia. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enthoven, P.; Skargren, E.; Carstensen, J.; Oberg, B. Predictive factors for 1-year and 5-year outcome for disability in a working population of patients with low back pain treated in primary care. Pain 2006, 122, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, A.; Patil, A.; Gunjal, P.; Naik, P.; Hubli, R. Effectiveness of three-dimensional myofascial release on lumbar lordosis in individuals with asymptomatic hyperlordosis: A placebo randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodyw. 2024, 17, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Ehsani, N.N.; Harrison, D.E. Non-surgical reduction of lumbar hyperlordosis, forward sagittal balance and sacral tilt to relieve low back pain by Chiropractic BioPhysics® methods: A case report. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2019, 31, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanayake, A.L.; Pathmeswaran, A.; Wijayaratne, L.S. Chronic low back pain and its association with lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral disc changes in adults. A case control study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 21, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, E.I.; Damen, J.; van Meurs, J.B.; Ginai, A.Z.; Popham, M.; Hofman, A.; Koes, B.W.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M. The association between lumbar disc degeneration and low back pain: The influence of age, gender, and individual radiographic features. Spine 2010, 35, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Normal Group | ALBP Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Max | Min | Mean ± SD | Max | Min | p Value | |

| Age (yrs) | 27.7 ± 8.5 | 52 | 18 | 28.1 ± 8 | 50 | 14 | p > 0.05 |

| Height (cm) | 171.5 $ | $ | $ | 174 $ | $ | $ | p > 0.05 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.8 $ | $ | $ | 74 $ | $ | $ | p > 0.05 |

| Sex | 29 Males, 21 Females | 29 Males, 21 Females | |||||

| ARA L1-L5 | −40.2 ± 9.5° | −22.1° | −62.9° | −40.9 ± 9.1° | −14.4° | −55.9° | p = 0.718 |

| ARA T12-S1 | −76.3 ± 9.9° | −47.8° | −97.3° | −77.5 ± 9.4° | −51.4° | −91.8° | p = 0.562 |

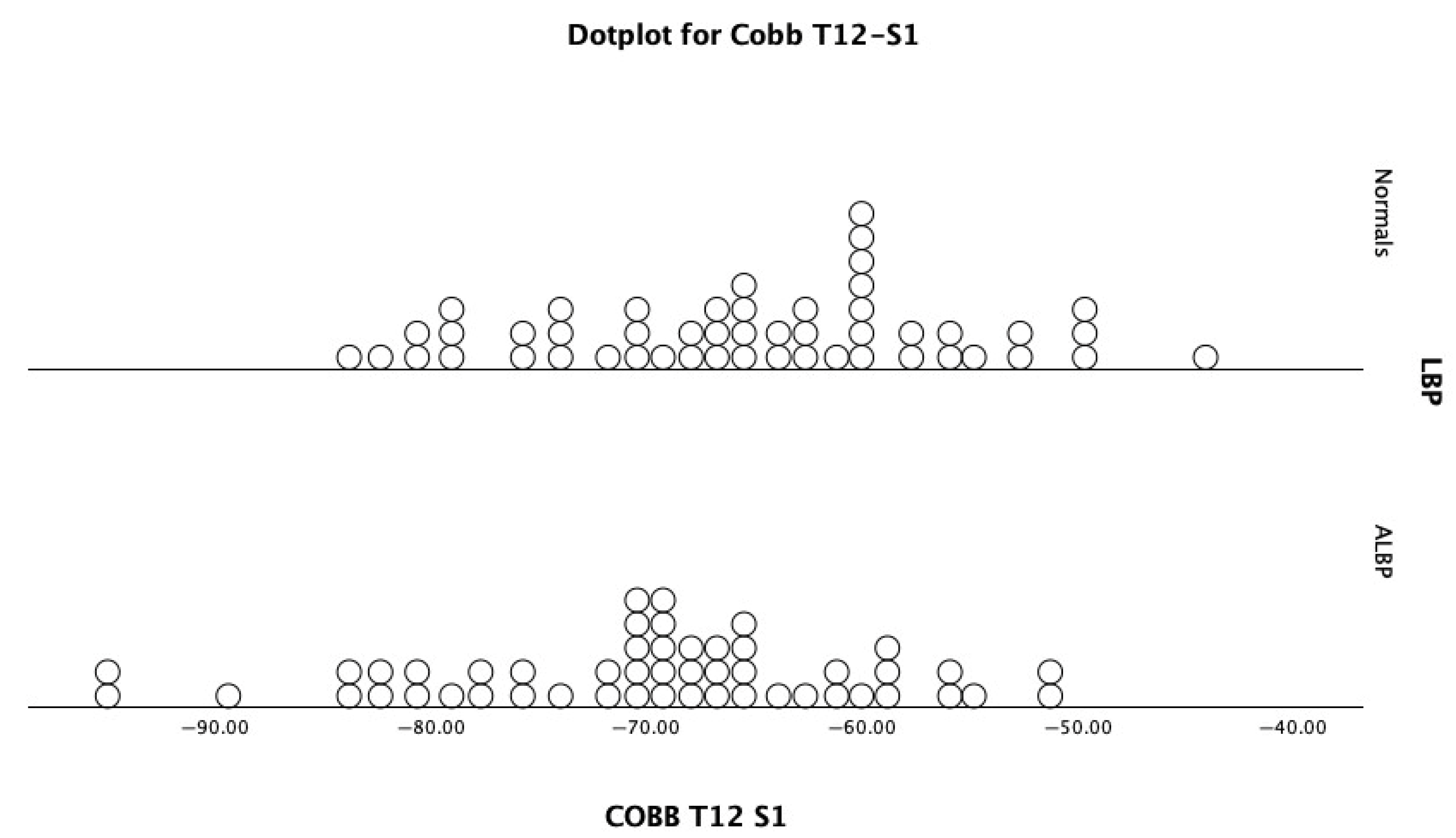

| Cobb T12-S1 | −65.4 ± 9.4° | −44.2° | −83.4° | −70.0 ± 10.1° | −51.4° | −95.5° | p = 0.021 * |

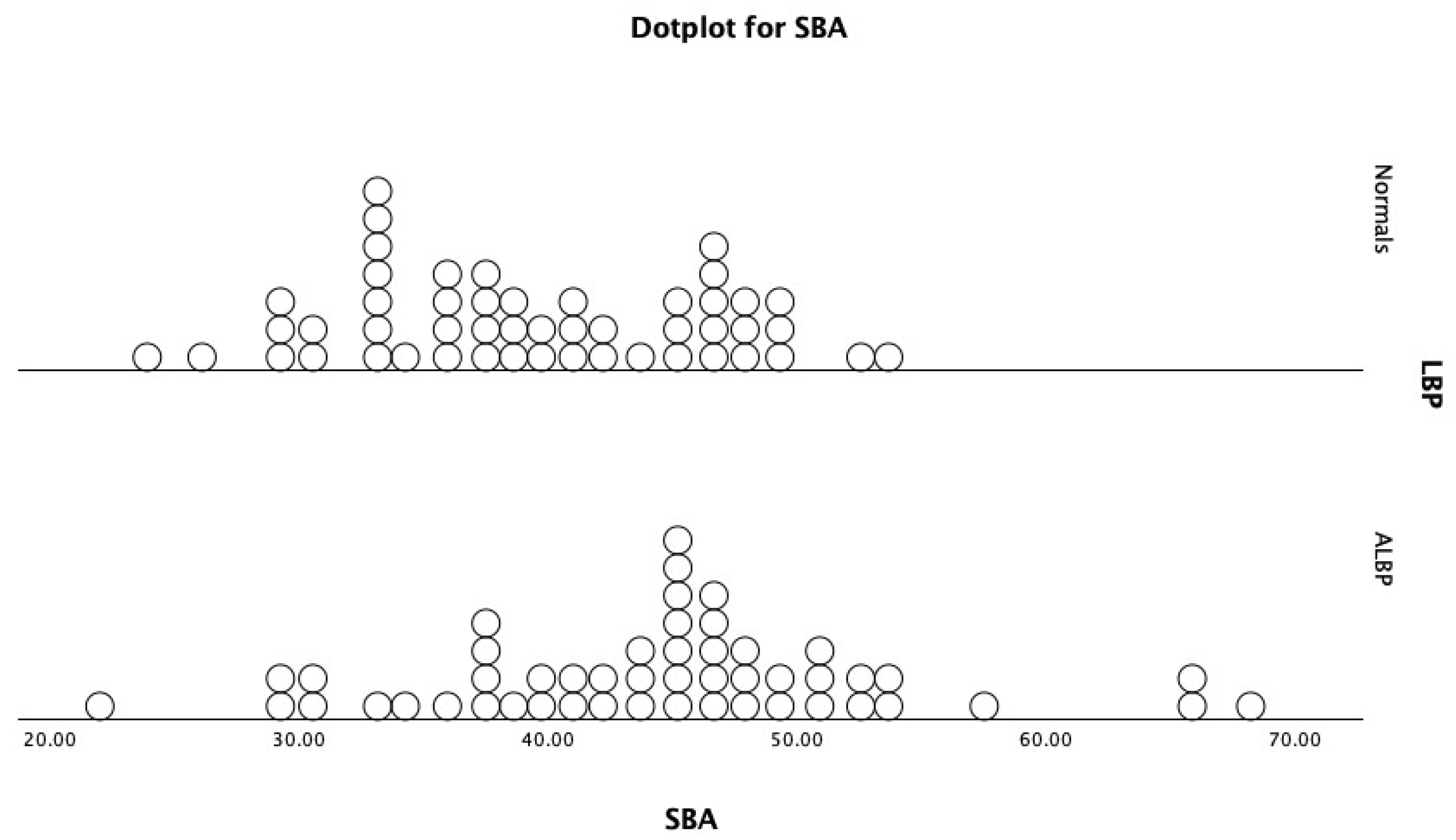

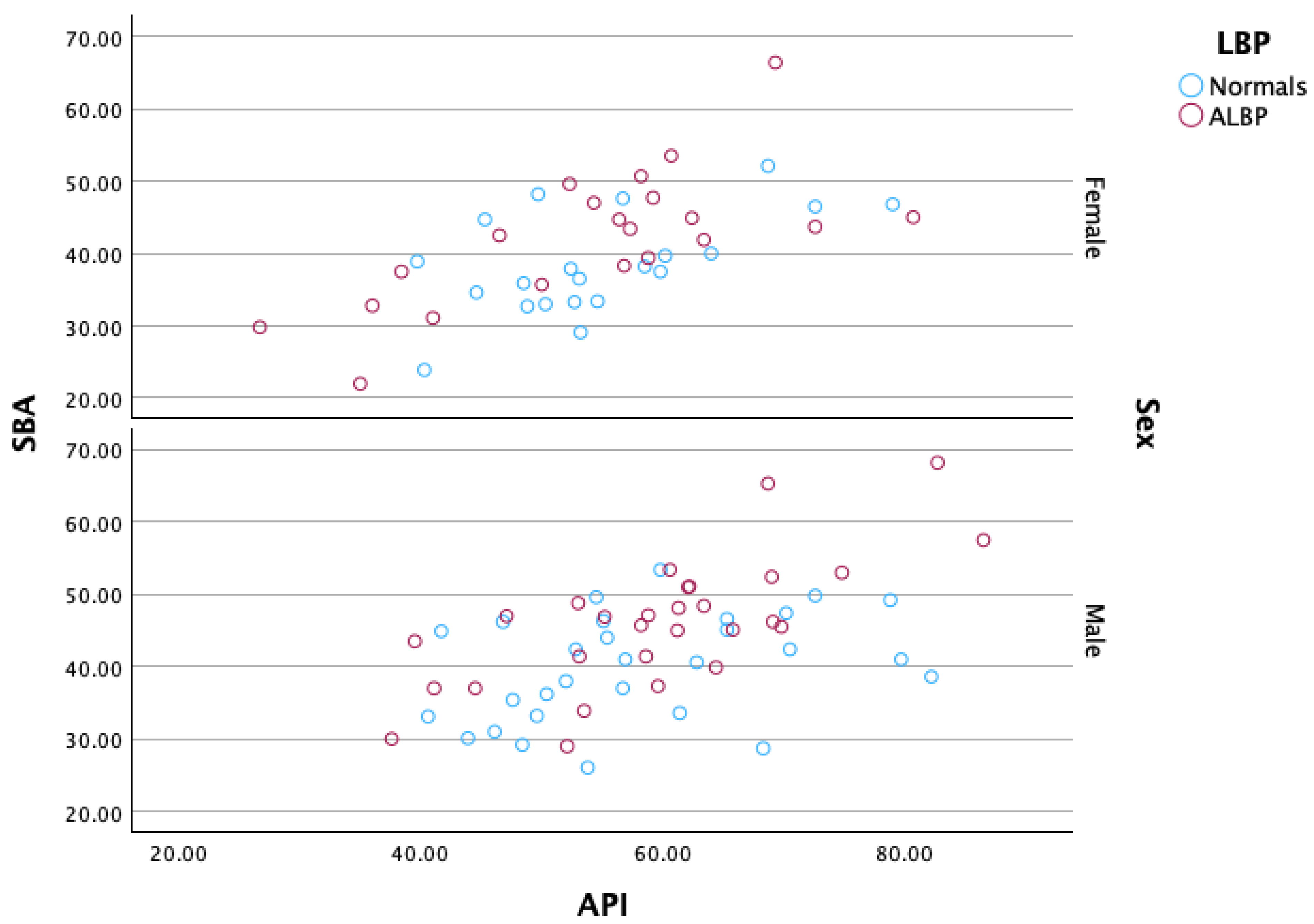

| SBA | 39.4 ± 7.2° | 53.4° | 23.9° | 44.5 ± 9.2° | 68.2° | 22° | p = 0.003 ** |

| PT-S1 | 50.3 ± 7.8° | 62.1° | 29.7° | 51.9 ± 7.8° | 67.9° | 33.9° | p = 0.310 |

| API | 56.8 ± 11° | 82.2° | 40.6° | 57.4 ± 12.5° | 86.5° | 35° | p = 0.815 |

| PTPIA | 73.9 ± 8.9° | 92.9° | 57.1° | 70.6 ± 9.5° | 93.7° | 55.8° | p = 0.076 a |

| b/a | 0.389 ± 0.147 | 0.874 | 0.150 | 0.389 ± 0.23 | 1.5 | 0.027 | p = 0.996 |

| API–ARA T12-S1 | −19.5 ± 14.4° | 13.8° | −47.6° | −20.1 ± 15.4° | 16.3° | −55.9° | p = 0.850 |

| API–ARA L1-L5 | 16.6 ± 11.5° | 40° | −7.8° | 16.5 ± 13.6° | 40.9° | −15.3° | p = 0.962 |

| API–Cobb T12-S1 | −8.6 ± 12.9° | 18.9° | −33.7° | −12.6 ± 10.7° | 8.3° | −31.3° | p = 0.092 a |

| Group | Variable | PTS1 | ARA T12S1 | Cobb T12S1 | ARA L1L5 | SBA | API | PTPIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ||||||||

| SBA | 0.799 ** p < 0.001 | −0.602 ** p < 0.001 | −0.731 ** p < 0.001 | −0.592 ** p < 0.001 | ||||

| API | 0.248 p = 0.083 | −0.059 p = 0.685 | −0.215 p = 0.134 | −0.325 * p = 0.021 | 0.492 ** p < 0.001 | |||

| PTPIA | 0.504 ** p < 0.001 | −0.248 p = 0.082 | −0.197 p = 0.171 | −0.305 * p = 0.031 | 0.460 ** p < 0.001 | 0.850 ** p < 0.001 | ||

| b/a | 0.174 p = 0.228 | −0.355 * p = 0.011 | −0.596 ** p < 0.001 | −0.609 ** p < 0.001 | 0.461 ** p < 0.001 | 0.195 p = 0.174 | 0.055 p = 0.704 | |

| Acute pain | ||||||||

| SBA | 0.329 * p = 0.020 | −0.324 * p = 0.022 | −0.862 ** p < 0.001 | −0.469 ** p < 0.001 | ||||

| API | 0.102 p = 0.482 | −0.059 p = 0.685 | −0.539 ** p < 0.001 | −0.239 p = 0.095 | 0.658 ** p < 0.001 | |||

| PTPIA | 0.628 ** p < 0.001 | −0.465 ** p < 0.001 | −0.074 p = 0.611 | −0.141 p = 0.330 | 0.108 p = 0.455 | 0.488 ** p < 0.001 | ||

| b/a | 0.054 p = 0.707 | −0.334 * p = 0.018 | −0.307 ** p = 0.030 | −0.376 ** p = 0.007 | 0.143 p = 0.320 | 0.001 p = 0.997 | 0.052 p = 0.718 |

| Groups | Variable | AUC | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal vs. Acute | ARA L1-L5 | 0.457 | −56.2° | 1.0 | 0.08 |

| ARA T12-S1 | 0.445 | −66.8° | 0.16 | 0.92 | |

| Cobb T12-S1 | 0.374 | −43.2° | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| SBA | 0.665 | 41.2° | 0.70 | 0.62 | |

| PT-S1 | 0.555 | 49.5° | 0.68 | 0.48 | |

| API | 0.542 | 57.1° | 0.58 | 0.62 | |

| PTPIA | 0.399 | 93.1° | 0.04 | 0.0 | |

| b/a | 0.475 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.48 | |

| API–ARA T12-S1 | 0.498 | −27.6° | 0.76 | 0.34 | |

| API–ARA L1-L5 | 0.506 | 14.8° | 0.64 | 0.48 | |

| API–Cobb T12-S1 | 0.412 | −32.5° | 1.00 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oakley, P.A.; Moustafa, I.M.; Betz, J.W.; Jaeger, J.O.; Harrison, D.E. Sensitivity and Specificity of Elliptical Modeling and Sagittal Lumbar Alignment Variables in Normal vs. Acute Low Back Pain Patients: Does Pelvic Morphology Explain Group Lordotic Differences? Healthcare 2025, 13, 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233163

Oakley PA, Moustafa IM, Betz JW, Jaeger JO, Harrison DE. Sensitivity and Specificity of Elliptical Modeling and Sagittal Lumbar Alignment Variables in Normal vs. Acute Low Back Pain Patients: Does Pelvic Morphology Explain Group Lordotic Differences? Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233163

Chicago/Turabian StyleOakley, Paul A., Ibrahim M. Moustafa, Joseph W. Betz, Jason O. Jaeger, and Deed E. Harrison. 2025. "Sensitivity and Specificity of Elliptical Modeling and Sagittal Lumbar Alignment Variables in Normal vs. Acute Low Back Pain Patients: Does Pelvic Morphology Explain Group Lordotic Differences?" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233163

APA StyleOakley, P. A., Moustafa, I. M., Betz, J. W., Jaeger, J. O., & Harrison, D. E. (2025). Sensitivity and Specificity of Elliptical Modeling and Sagittal Lumbar Alignment Variables in Normal vs. Acute Low Back Pain Patients: Does Pelvic Morphology Explain Group Lordotic Differences? Healthcare, 13(23), 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233163