Lipid-Derived Cardiometabolic Indices in Normouricemic and Hyperuricemic Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Association Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

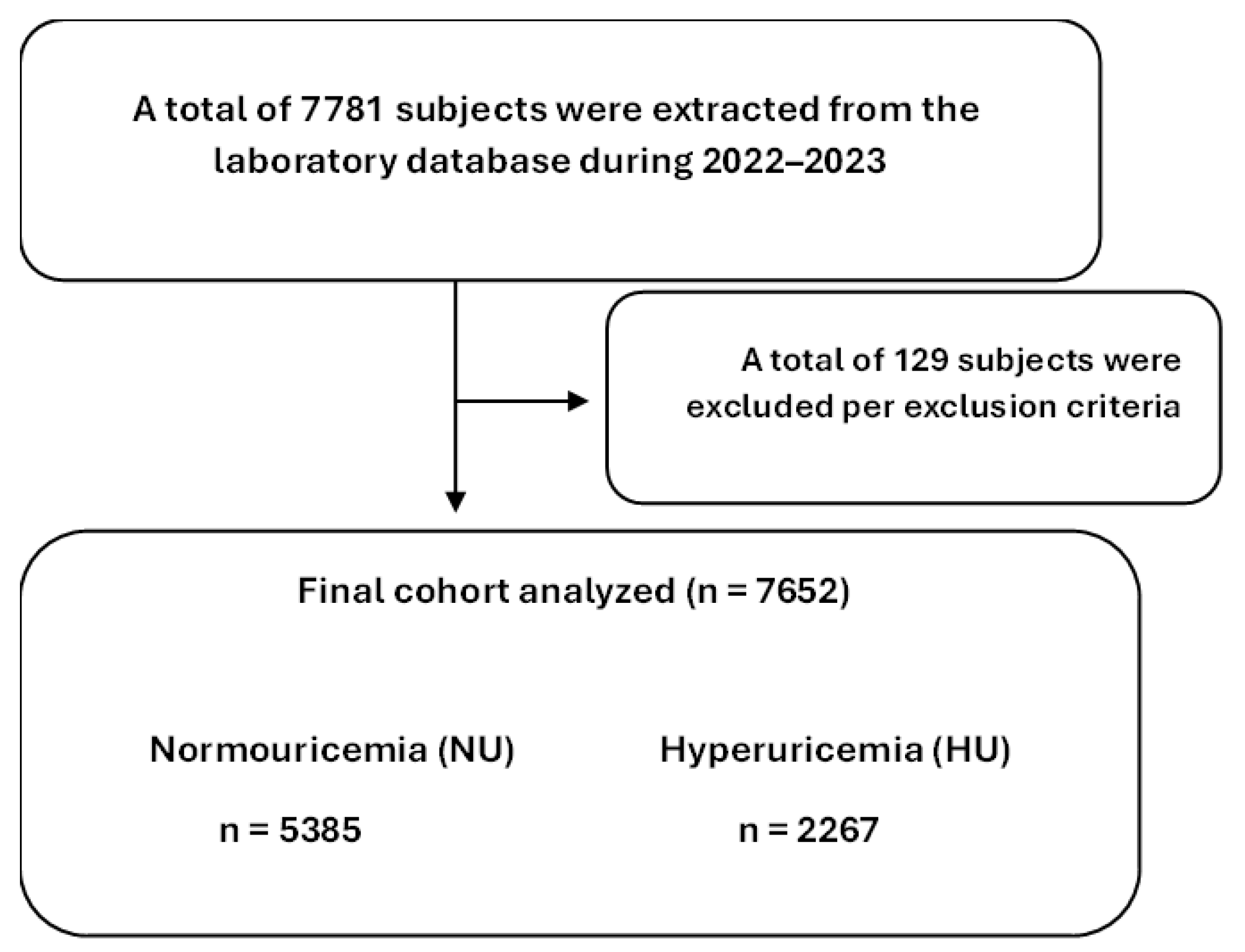

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Biochemical and Hematological Characteristics by Uricemia Status

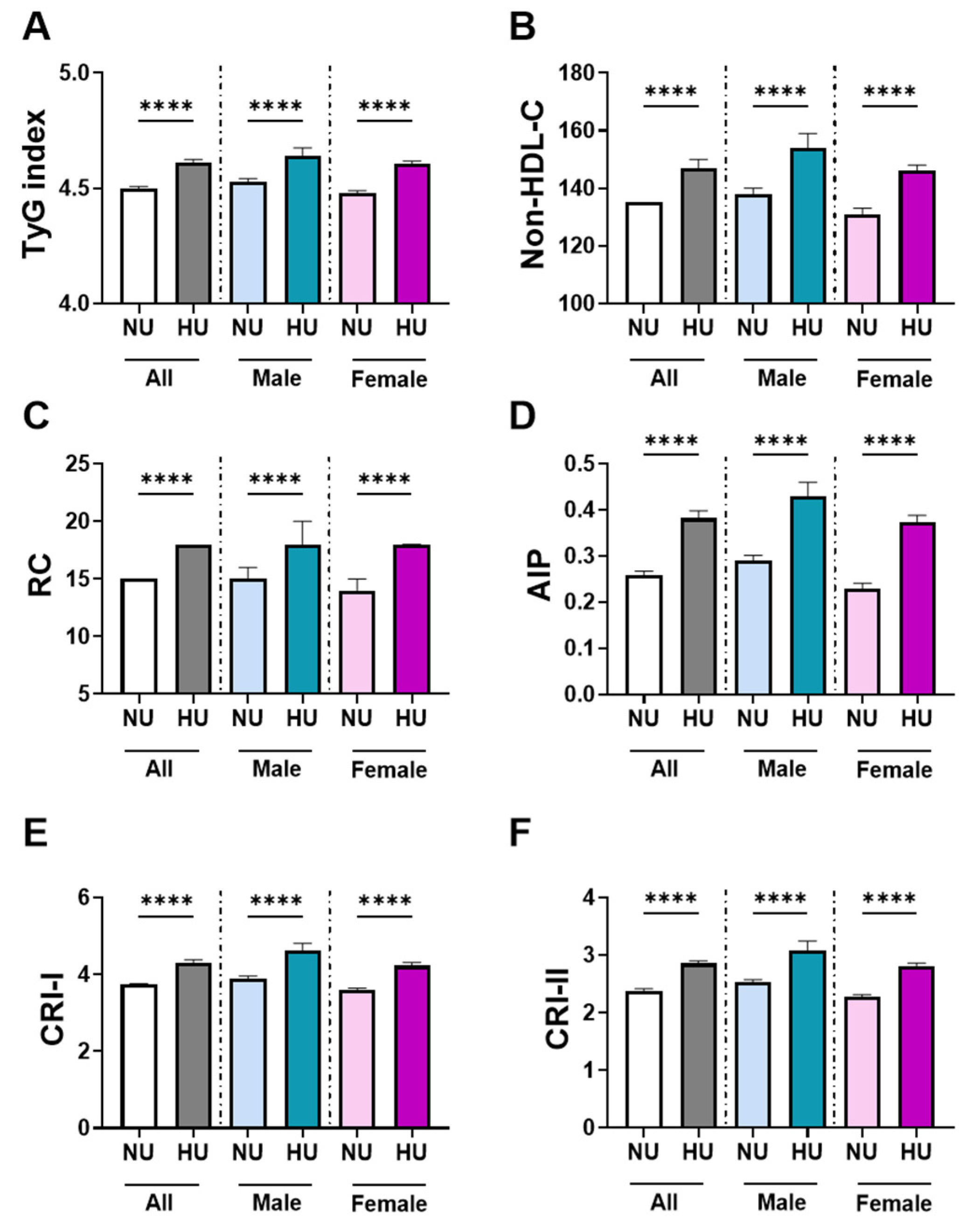

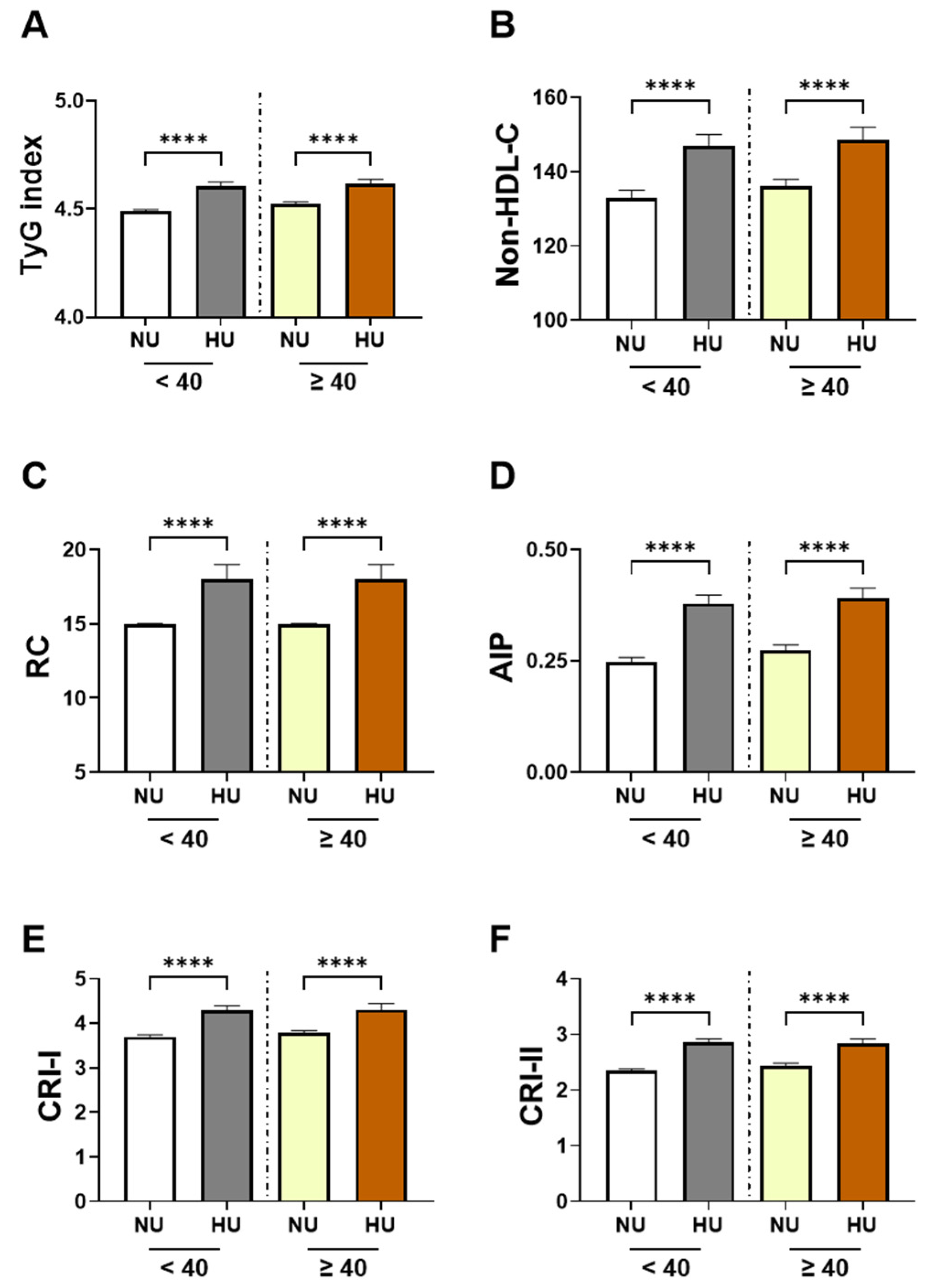

3.2. Sex and Age-Specific Analysis in Cardiometabolic Indices by Uricemia Status

3.3. Multivariable Associations Between HU and Cardiometabolic Indices

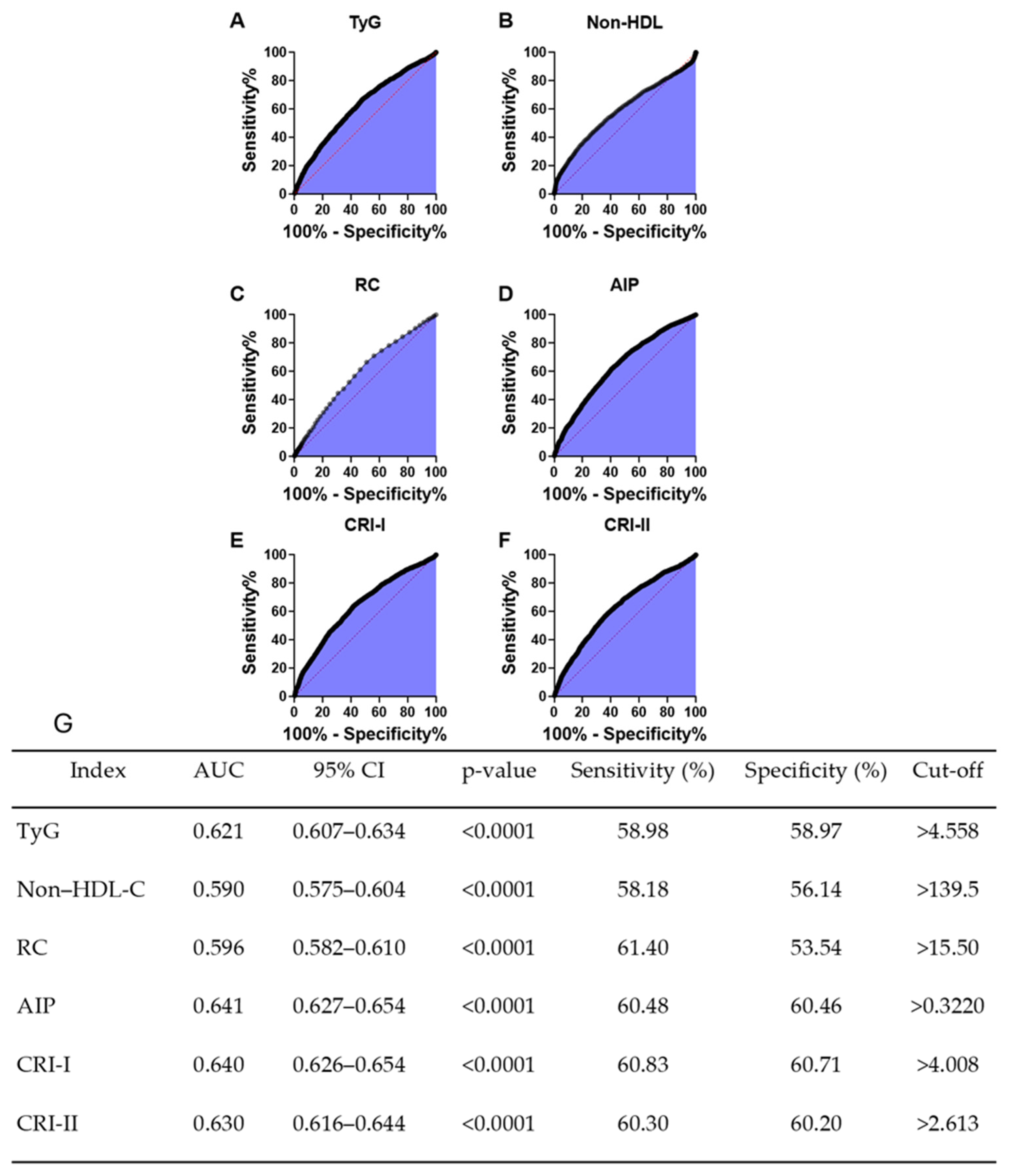

3.4. Discrimnatory Performance of HU for Cardiometabolic Indices

3.5. Prevalence of Elevated Cardiometabolic Indices in HU

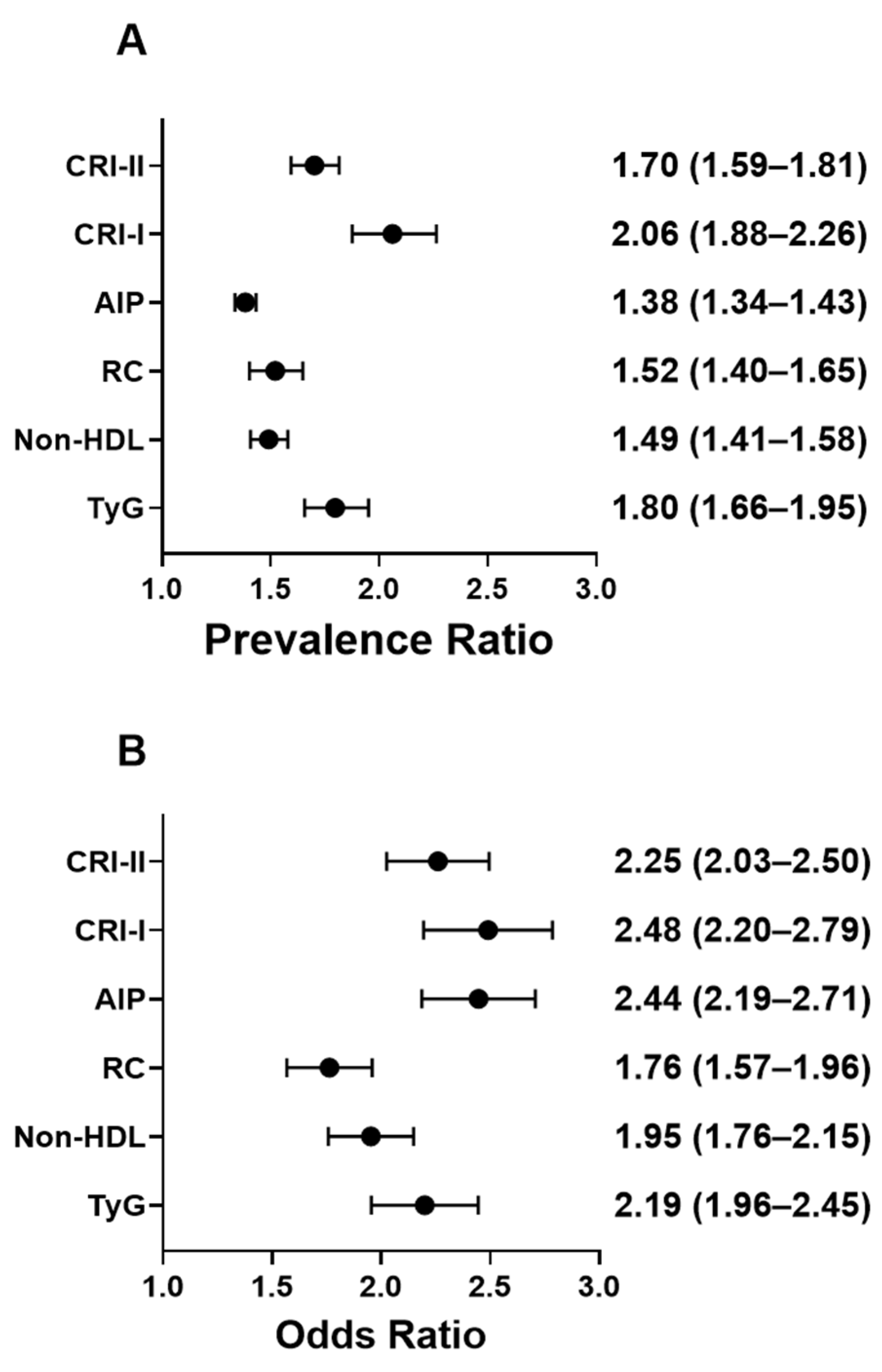

3.6. HU-Associated Prevalence Estimates for Cardiometabolic Indices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skoczyńska, M.; Chowaniec, M.; Szymczak, A.; Langner-Hetmańczuk, A.; Maciążek-Chyra, B.; Wiland, P. Pathophysiology of hyperuricemia and its clinical significance—A narrative review. Reumatologia 2020, 58, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiullah, M.; Siddiqui, K.; Al-Rubeaan, K. Association between serum uric acid levels and metabolic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes from a community with high diabetes prevalence. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 74, e13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAteeq, M.A.; Almaneea, A.; Althaqeb, E.K.; Aljarallah, M.F.; Alsaleh, A.E.; Alrasheed, M.A. Uric Acid Levels in Overweight and Obese Children, and Their Correlation with Metabolic Risk Factors. Cureus 2024, 16, e70160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuqrin, A.; Alshuweishi, Y.A.; Alfaifi, M.; Daghistani, H.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Alfhili, M.A. Prevalence and association of hyperuricemia with liver function in Saudi Arabia: A large cross-sectional study. Ann. Saudi Med. 2024, 44, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arfaj, A.S. Hyperuricemia in Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol. Int. 2001, 20, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Zhao, R.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, H.; Lu, C. Hyperuricemia is associated with metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, T.; Xu, Y.; Yan, X.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Xing, X.; Chen, Q.; Yang, W. Nonlinear dose-response association of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity with hyperuricemia in US adults: NHANES 2007–2018. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.N.; Yue, W.W.; Yu, H.P.; Liu, C.X.; Yin, J.; Jia, R.Y.; Nie, H.W. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in China: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Li, C.; Zheng, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, L.; Yu, J. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Hyperuricemia in Urban Chinese Check-Up Population. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 2024, 8815603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; Bawazeer, N.; Al Farsi, Y.; Youssef, A.M.; Al-Yahya, A.A.; AlQumaidi, H.; Al-Malki, B.M.; Naji, K.A.; Al-Shehri, K.; Al Rumaih, F.I. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Saudi Arabia—A cross sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusseini, N.; Alsinan, N.; Almutahhar, S.; Khader, M.; Tamimi, R.; Elsarrag, M.I.; Warar, R.; Alnasser, S.; Ramadan, M.; Omair, A.; et al. Dietary trends and obesity in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1326418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Dong, B.; Geng, Z.; Xu, L. Excess Uric Acid Induces Gouty Nephropathy Through Crystal Formation: A Review of Recent Insights. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 911968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnini, C.; Russo, E.; Leoncini, G.; Ghinatti, M.C.; Macciò, L.; Piaggio, M.; Viazzi, F.; Pontremoli, R. Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia and the Kidney: Lessons from the URRAH Study. Metabolites 2025, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, J.; Song, C.; Sun, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yin, J.; et al. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia associated with increased risk of nephrolithiasis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhou, E.; Wu, J. Association between hyperuricemia and long-term mortality in patients with hypertension: Results from the NHANES 2001–2018. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1306026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, R.G.; Richardson, K.A.; Richardson, L.T. Uric acid and metabolic syndrome: Findings from national health and nutrition examination survey. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1039230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Du, G.-L.; Song, N.; Ma, Y.-T.; Li, X.-M.; Gao, X.-M.; Yang, Y.-N. Hyperuricemia and its association with adiposity and dyslipidemia in Northwest China: Results from cardiovascular risk survey in Xinjiang (CRS 2008–2012). Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Mao, S.; Yin, X.; Guo, L. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, X.; Fan, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.; Hou, W.; Tang, Z. Hyperuricemia and the risk for coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Miao, M.; Xu, C. Association between serum uric acid levels and dyslipidemia in Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study and further meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e19088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, M. Hyperuricemia as a possible risk factor for abnormal lipid metabolism in the Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 11454–11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloberti, A.; Vanoli, J.; Finotto, A.; Bombelli, M.; Facchetti, R.; Redon, P.; Mancia, G.; Grassi, G. Uric acid relationships with lipid profile and adiposity indices: Impact of different hyperuricemic thresholds. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 25, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, N.; Li, S.; Dou, J. The predictive significance of the triglyceride-glucose index in forecasting adverse cardiovascular events among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with co-existing hyperuricemia: A retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varbo, A.; Benn, M.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Elevated remnant cholesterol causes both low-grade inflammation and ischemic heart disease, whereas elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol causes ischemic heart disease without inflammation. Circulation 2013, 128, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaha, M.J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Brinton, E.A.; Jacobson, T.A. The importance of non-HDL cholesterol reporting in lipid management. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2008, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsin, A.; Kaya, H.; Suner, A.; Uzel, K.E.; Bursa, N.; Hosoglu, Y.; Yavuz, F.; Asoglu, R. Plasma atherogenic indices are independent predictors of slow coronary flow. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borai, A.; Ichihara, K.; Al Masaud, A.; Tamimi, W.; Bahijri, S.; Armbuster, D.; Bawazeer, A.; Nawajha, M.; Otaibi, N.; Khalil, H.; et al. Establishment of reference intervals of clinical chemistry analytes for the adult population in Saudi Arabia: A study conducted as a part of the IFCC global study on reference values. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Lin, J.; Wan, J.; Zhao, M. The atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) is a predictor for the severity of coronary artery disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1140215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Jee, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Jin, S.-M.; Suh, S.; Bae, J.C.; Kim, S.W.; Chung, J.H.; Min, Y.-K.; Lee, M.-S.; et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol is a better predictor of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance than apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2678–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Tian, N.; Xu, Q.; Zhan, X.; Peng, F.; Wang, X.; Su, N.; Feng, X.; Tang, X.; et al. Association of the remnant cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primo, D.; Izaola, O.; De Luis, D.A. Triglyceride-Glucose Index Cutoff Point Is an Accurate Marker for Predicting the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Caucasian Subjects. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 79, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, A.; Das Trisha, A.; Ahmed, S.; Begum, J.; Sinha, F.; Sarna, N.Z.; Ali, N. Investigating the Relationship Between Serum Uric Acid and Dyslipidemia in Young Adults in Bangladesh. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yao, Y.; Wang, F.; He, W.; Sun, T.; Li, H. A study on the correlation between hyperuricemia and TG/HDL-c ratio in the Naxi ethnic group at high-altitude regions of Yunnan. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1416021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, L. Reactive oxygen species: Key regulators in vascular health and diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battelli, M.G.; Polito, L.; Bortolotti, M.; Bolognesi, A. Xanthine Oxidoreductase-Derived Reactive Species: Physiological and Pathological Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2016, 3527579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushiyama, A.; Okubo, H.; Sakoda, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Fujishiro, M.; Sato, H.; Kushiyama, S.; Iwashita, M.; Nishimura, F.; Fukushima, T.; et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase is involved in macrophage foam cell formation and atherosclerosis development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, M.; Nardi, V.; Prasad, M.; Jordan, K.L.; Bois, M.C.; Franchi, F.; Zhu, X.Y.; Tang, H.; Young, M.D.; Lerman, L.O.; et al. Carotid Plaques from Symptomatic Patients Are Characterized by Local Increase in Xanthine Oxidase Expression. Stroke 2021, 52, 2792–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, X.-L.; Fu, C.; Han, R.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y.; Ye, Z. Soluble uric acid increases NALP3 inflammasome and interleukin-1β expression in human primary renal proximal tubule epithelial cells through the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Han, A.; Song, J.; Zhou, X.; Song, W. Renal NF-κB activation impairs uric acid homeostasis to promote tumor-associated mortality independent of wasting. Immunity 2022, 55, 1594–1608.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xu, Y.; Shao, X.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Zuo, Z.; Shao, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Uric Acid Produces an Inflammatory Response through Activation of NF-κB in the Hypothalamus: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husejko, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Gackowski, M.; Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Wojtasik, J.; Strzała, D.; Pesta, M.; Ciesielska, J.; Ratajczak, D.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Higher uric acid associated with elevated IL-6 and IL-1β levels in older inpatients: A cross-sectional study. Rheumatol. Int. 2025, 45, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngdoh, T.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Paccaud, F.; Preisig, M.; Waeber, G.; Bochud, M.; Vollenweider, P. Elevated serum uric acid is associated with high circulating inflammatory cytokines in the population-based colaus study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, T.O.; Cleophas, M.C.P.; Oosting, M.; Lemmers, H.; Toenhake-Dijkstra, H.; Netea, M.G.; Jansen, T.L.; Joosten, L.A.B. Soluble uric acid primes TLR-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by human primary cells via inhibition of IL-1Ra. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Y. Hyperuricemia-induced complications: Dysfunctional macrophages serve as a potential bridge. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1512093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. The Effects of Allopurinol on the Carotid Intima-media Thickness in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia: A Three-year Randomized Parallel-controlled Study. Intern. Med. 2015, 54, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takir, M.; Kostek, O.; Ozkok, A.; Elcioglu, O.C.; Bakan, A.; Erek, A.; Mutlu, H.H.; Telci, O.; Semerci, A.; Odabas, A.R.; et al. Lowering uric acid with allopurinol improves insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in asymptomatic hyperuricemia. J. Investig. Med. 2015, 63, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian-Valles, F.; Muñiz, Á.M.; Marazuela, M. Remnant Cholesterol: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications in Type 1 Diabetes. Endocrines 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, E.P.; Burini, R.C. High plasma uric acid concentration: Causes and consequences. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2012, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, H.L.; Wilson, F.A.; Hefferan, P.; Terry, A.B.; Moran, J.R.; Slonim, A.E.; Claus, T.H.; Burr, I.M. ATP depletion, a possible role in the pathogenesis of hyperuricemia in glycogen storage disease type I. J. Clin. Investig. 1978, 62, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zou, R.; Du, X.; Li, K.; Sha, D. Association of remnant cholesterol with decreased kidney function or albuminuria: A population-based study in the U.S. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, C.; Zhou, H.; Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, M. Association of Remnant Cholesterol with Rapid Kidney Function Decline in Middle-Aged and Older Adults with Normal Kidney Function. Kidney Dis. 2025, 11, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Yu, B.; Liang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, H.; Lin, J. The role of remnant cholesterol beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, S.; Guo, X. The associations between fasting glucose, lipids and uric acid levels strengthen with the decile of uric acid increase and differ by sex. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 2786–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baral, S.; Kshetri, R.; Mandel, L. Association of HbA1c, Serum Uric Acid and Non-HDL Cholesterol in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Metabolism 2020, 104, 154063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M. Gout and hyperuricaemia: Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1190069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Wu, B.; Mehta, S.; Harwood, M.; Grey, C.; Dalbeth, N.; Wells, S.M.; Jackson, R.; Poppe, K. Association between gout and cardiovascular outcomes in adults with no history of cardiovascular disease: Large data linkage study in New Zealand. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Normouricemia | Hyperuricemia | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 (32–46) | 36 (32–45) | >0.999 |

| Red cell count (×106/µL) | 5.14 (4.80–5.54) | 5.53 (5.09–5.89) | 0.1318 |

| Total leucocytic count (×103/µL) | 5.57 (4.49–6.90) | 5.86 (4.73–7.15) | >0.999 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 88 (67–120) | 107 (79–144) | 0.0040 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49 (42–57) | 44 (37–51) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 117 (99–137) | 127 (101–149) | >0.999 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 185 (165–206) | 193 (165–216) | >0.999 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 91 (85–98) | 94 (88–102) | >0.999 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.70 (0.60–0.80) | 0.80 (0.70–0.98) | 0.4543 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 21 (17–27) | 22 (11–29) | 0.0142 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L) | 16 (12–24) | 23 (16–33) | <0.001 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (U/L) | 17 (15–22) | 20 (16–25) | 0.0142 |

| Model | Index | β (95% CI) | VIF | R2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | TyG | 1.58 (1.41–1.76) | 1.00 | 0.040 | <0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.14 (0.11–0.18) | 1.00 | 0.007 | <0.0001 | |

| RC | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) | 1.00 | 0.022 | <0.0001 | |

| AIP | 0.18 (0.17–0.20) | 1.00 | 0.065 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-I | 0.37 (0.34–0.40) | 1.00 | 0.059 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-II | 0.24 (0.22–0.26) | 1.00 | 0.045 | <0.0001 | |

| Model 2 | TyG | 1.57 (1.40–1.74) | 1.00 | 0.042 | <0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.14 (0.10–0.18) | 1.00 | 0.012 | <0.0001 | |

| RC | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) | 1.00 | 0.025 | <0.0001 | |

| AIP | 0.18 (0.17–0.20) | 1.00 | 0.067 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-I | 0.36 (0.33–0.40) | 1.00 | 0.062 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-II | 0.24 (0.21–0.26) | 1.00 | 0.048 | <0.0001 | |

| Model 3 | TyG | 1.17 (0.97–1.37) | 1.03 | 0.317 | <0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.09 (0.05–0.13) | 1.04 | 0.302 | <0.0001 | |

| RC | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | 1.03 | 0.306 | <0.0001 | |

| AIP | 0.13 (0.11–0.15) | 1.06 | 0.324 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-I | 0.26 (0.22–0.30) | 1.10 | 0.321 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-II | 0.17 (0.14–0.20) | 1.08 | 0.316 | <0.0001 | |

| Model 4 | TyG | 0.94 (0.77–1.12) | 1.11 | 0.105 | <0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.01 (–0.02–0.05) | 1.08 | 0.092 | 0.48 | |

| RC | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) | 1.05 | 0.100 | <0.0001 | |

| AIP | 0.13 (0.11–0.14) | 1.14 | 0.119 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-I | 0.23 (0.20–0.26) | 1.17 | 0.112 | <0.0001 | |

| CRI-II | 0.14 (0.11–0.16) | 1.15 | 0.106 | <0.0001 |

| Variable | NU (%) | HU (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated TyG (>4.72) | 18.3 | 32.9 | <0.0001 |

| Elevated Non-HDL-C (≥150 mg/dL) | 32.3 | 48.2 | <0.0001 |

| Elevated RC (≥24 mg/dL) | 20.5 | 31.1 | <0.0001 |

| Elevated AIP (>0.24) | 53.0 | 73.3 | <0.0001 |

| Elevated CRI-I (>5) | 13.7 | 28.2 | <0.0001 |

| Elevated CRI-II (>3) | 25.9 | 44.0 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshuweishi, Y.; Khobrani, S.H.; Alsaidan, M.; Alharthi, T.M.; Abdelgader, M.G.; Almuqrin, A.M. Lipid-Derived Cardiometabolic Indices in Normouricemic and Hyperuricemic Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Association Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233151

Alshuweishi Y, Khobrani SH, Alsaidan M, Alharthi TM, Abdelgader MG, Almuqrin AM. Lipid-Derived Cardiometabolic Indices in Normouricemic and Hyperuricemic Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Association Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233151

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshuweishi, Yazeed, Salihah H. Khobrani, Muath Alsaidan, Tahani M. Alharthi, Mohannad G. Abdelgader, and Abdulaziz M. Almuqrin. 2025. "Lipid-Derived Cardiometabolic Indices in Normouricemic and Hyperuricemic Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Association Study" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233151

APA StyleAlshuweishi, Y., Khobrani, S. H., Alsaidan, M., Alharthi, T. M., Abdelgader, M. G., & Almuqrin, A. M. (2025). Lipid-Derived Cardiometabolic Indices in Normouricemic and Hyperuricemic Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Association Study. Healthcare, 13(23), 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233151