Sustainable Workplaces and Employee Well-Being: A Systematic Review of ESG-Linked Physical Activity Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Trends in Workplace Health Promotion

1.2. Personal Psychological-Level Benefits and Work-Related Outcomes of WPABPs

1.3. Need for Systematic Synthesis and Evidence Clarity

1.4. Theoretical Mechanisms

1.4.1. ESG

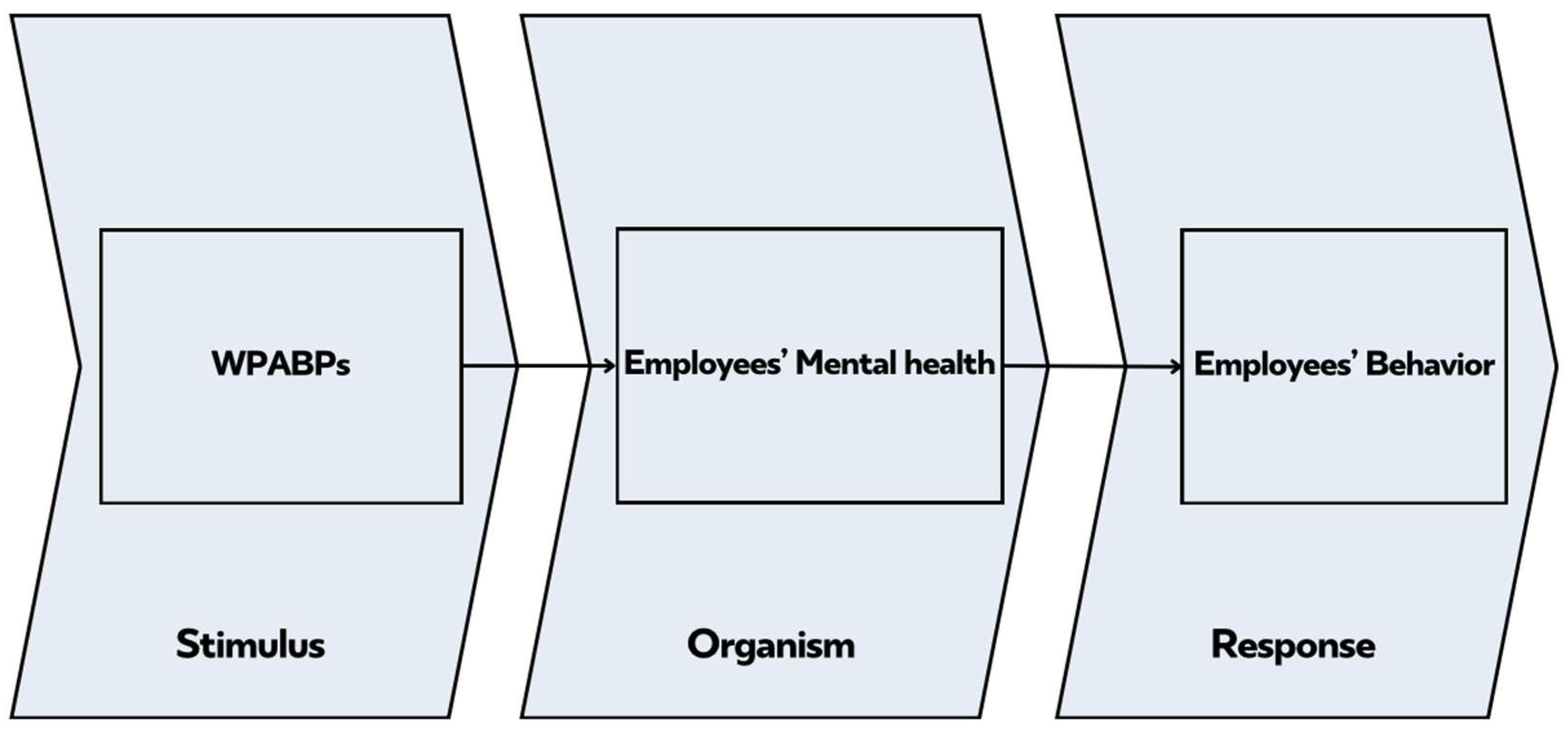

1.4.2. S–O–R Theory and Applications

1.5. Research Objectives

1.6. The Significance of Research and Review Scope

- Responding to global trends in workplace health promotion by systematically synthesizing empirical evidence on WPABPs to clarify their integrated effects on mental health and work-related outcomes.

- Highlighting the linkage with the ESG-S, examining how WPABPs contribute to sustainable business practices.

- Applying the S–O–R theoretical framework to explain how WPABPs function as external stimuli that influence employees’ internal psychological states and behavioral responses.

- Bridging the gap between research methods and practical application to guide future interventions aimed at reducing workplace health inequities.

2. Methods

2.1. Database Selection and Source Justification

2.2. Keyword Strategy and Boolean Search Logic

2.3. Screening and Methodological Quality Assessment

2.4. Three-Stage Literature Search Strategy

- Stage 1: Preliminary Screening

- Stage 2: Systematic Database Search

- Stage 3: Synthesis and Validation

2.5. Reference Management and Initial Search Results by Database

3. Results

| Author | Year | Title | Intervention Intensity | Type | Participants | Country and Industry | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brailovskaia et al. [41] | 2024 | Less smartphone and more physical activity for a better work satisfaction, motivation, work-life balance, and mental health: an experimental intervention study | Moderate-intensity aerobic and behavioral regulation program, 6-week intervention, 30 min/day increase | Test combining PA increase and smartphone-use control | Employees across different professional sectors and workplaces (n = 278) | Germany, mixed workplaces (private and public; multiple industries) | Reduced smartphone use combined with PA interventions significantly improved job satisfaction, motivation, work–life balance, and positive mental health, while reducing work overload and problematic phone use. |

| Candelario et al. [46] | 2024 | Integrative review of workplace health promotion in the business process outsourcing industry: focus on the Philippines | Varied (incorporating different intensities, durations, types, and frequencies of exercise) | Integrative review (n = 37 studies) | Target population: BPO workers described in included studies (n = 261,262) | The Philippines, the BPO industry (private sector) | BPO workers face elevated risks of physical and psychological strain, sleep disorders, and occupational diseases due to the inherent demands of their work. |

| Msuya & Kumar [44] | 2022 | Nexus between workplace health and employee wellness programs and employee performance | Not reported (survey) | Cross-sectional/ survey study | Banking employees (n = 252) | Tanzania, Financial industry (banking), private/public banking sector | A significant positive relationship was found between workplace health and wellness programs and employee job performance. |

| Paramashiva et al. [47] | 2025 | Enhancing well-being at work: qualitative insights into challenges and benefits of long-term yoga programs for desk-based workers | Varied (yoga intensity moderate/low; long-term programs) | Semi-structured interviews with a long-term yoga program | Participants in a long-term workplace yoga program (desk-based or remote workers, n = 6) | India, Division of Yoga, Manipal Academy (educational/research setting) | Among remote workers, strong correlations were observed between attendance, daily stress, stress relief, sleep quality, work purpose, and life satisfaction. Remote work stress and sleep quality were strongly related to stress relief and work purpose. |

| Singh et al. [12] | 2024 | Evaluation of the “15-min challenge”: a workplace health and wellbeing program | 15 min daily PA sessions (light–moderate) for six weeks. | mHealth gamified program (team competition and activity logging) | Employees from multiple workplaces participating in the “15-Minute Challenge” (n = 73) | Australia, New Zealand, UK, mixed workplaces (mostly private/organizational settings) | Yoga participants reported challenges maintaining regular practice due to time constraints, initial discomfort, and varying motivation, yet noted substantial benefits in mental health and stress management. |

| Larisch et al. [21] | 2023 | “It depends on the boss”—a qualitative study of multi-level interventions aiming at office workers’ movement behaviour and mental health | During the six-month intervention period, (1) focused on increasing moderate-to-vigorous PA, (2) targeted replacing sedentary behavior with low-intensity PA. | Qualitative process evaluation of multi-level RCT interventions | Office workers (n = 38) | Sweden, office/white-collar workplaces (private and public offices) | The “15—Minute Challenge” effectively increased employee PA levels and improved self-reported health outcomes. High satisfaction and significant health improvements highlight the potential of workplace wellness programs to counter sedentary behavior and promote active lifestyles. |

| Bonatesta et al. [43] | 2024 | Short-term economic evaluation of physical activity-based corporate health programs: a systematic review | Varied (incorporating different intensities, durations, types, and frequencies of exercise) | Systematic review (n = 11 studies) | Multiple PA–based corporate health programs (n = 60,020) | Europe, Australia, and USA, corporate programs (predominantly private sector) | Office employees attributed improvements in movement behavior (particularly reduced sedentary) and well-being to the interventions, notably cognitive-behavioral therapy–based counseling and free gym access. Managerial and team support were identified as key facilitators. |

| Gil-Beltrán et al. [51] | 2020 | Get vigorous with physical exercise and improve your well-being at work! | Vigorous exercise emphasized (higher intensity) | Intervention/commentary promoting vigorous PA | Workplace samples (n = 485) | Spain and Latin America, private companies | Beyond fostering healthy lifestyles, PA-based corporate health programs demonstrate potential for generating substantial short-term economic returns. |

| Marin-Farrona et al. [19] | 2023 | Effectiveness of worksite wellness programs based on physical activity to improve workers’ health and productivity: a systematic review | Varied (Most RCTs ranged from 6 to over 12 weeks, incorporating different intensities, durations, types, and frequencies of exercise) | Systematic review of worksite PA programs (n = 16 studies) | Samples included healthcare workers, office and industrial workers, university staff, cleaners, postal workers (n = 36,623) | Multiple countries (Denmark, Norway, UK, Brazil, Germany, USA, Spain, Japan, The Netherlands, parts of Africa), mixed: healthcare (public), industrial (private), educational institutions, services | Operability was identified as the productivity variable most influenced by worksite programs based on PA, effectively enhancing both worker productivity and health. |

| Ford et al. [42] | 2022 | Impacts of a workplace physical activity intervention on employee physical activity & mental health for NHS staff in Wales: an evaluation of the pilot time to move initiative | Offers employees a 12-month program allowing one hour per week of paid time for participation in chosen physical activities. | Organizational initiative (Time to Move initiative; workplace PA program) | NHS staff in Wales (n= 625) | Wales is one of the four public sector healthcare systems under the UK | Providing paid time for PA yielded positive outcomes for many employees, including higher activity levels, improved mental health, and greater job satisfaction. |

| Munuo [45] | 2023 | Physical activity at work and job performance: a qualitative study of physical activity at work from the perspective of office workers in Tanzania. | At least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA per week. Interview: (a) prerequisites to be physically active at work (b) barriers to PA at work (c) how PA influences their job performance at work. | A qualitative study | Banking managers, senior and junior officers (n= 9) | Tanzania (Shinyanga Region), Financial industry (banking) | Regular movement in office settings contributed to better employee health and overall job performance, while workplace health promotion activities enhanced general well-being and cognitive functioning through exercise. |

| Martinez [52] | 2021 | The importance of workplace exercise | Varied (incorporating different intensities, durations, types, and frequencies of exercise) | Narrative review (n = 14 studies) | Workplace employees across various occupations | Brazil, Salvador (and other regions cited), mixed workplaces (private/organizational settings) | Workplace exercise directly improves employees’ quality of life, reducing the incidence of repetitive strain injuries, work-related musculoskeletal disorders, occupational stress, and burnout syndrome. |

| Rodrigues et al. [48] | 2021 | Trainer-exerciser relationship: the congruency effect on exerciser psychological needs using response surface analysis | Not reported (observational: looks at perceived interpersonal behavior quality) | Cross-sectional survey of trainer–exerciser interactions | Coaches (n = 130), gym exercisers (n = 640) | Portugal, private gyms/fitness industry (private sector) | Coaches tended to overreport supportive and underreport thwarting behaviors; alignment with exercisers’ perceptions improved basic need satisfaction, particularly regarding relatedness. |

| Casimiro-Andújar et al. [49] | 2022 | Effects of a personalised physical exercise program on university workers overall well-being: “UAL-Activa” program | Sessions are tailored to individual goals and fitness levels, conducted once per week for six months, each lasting 60 min. Including strength training, aerobics exercises etc. | Personal training/ individualized exercise program at a gym outside of work | University workers participating in a personalized exercise program (n = 25) | Spain, educational institution (university of Almeria staff; public university) | Participation in personalized, trainer-led exercise programs improved overall health and mood, producing a notably positive impact on the work environment. |

| Gil-Beltrán et al. [50] | 2024 | How physical exercise with others and prioritizing positivity contribute to (work) wellbeing: a cross-sectional and diary multilevel study | Exercise was measured by weekly frequency, session duration, and intensity (0–5 scale). | Cross-sectional + diary multilevel study; group exercise settings | Study 1 (n = 553) and Study 2 (n = 146) focused on group exercise during confinement. | Spain, mixed (community/worker samples; private and public settings) | Higher engagement and positive affect promoted greater exercise participation, particularly in positive social contexts. Prioritizing positive emotions also preceded and reinforced positive affect during exercise, creating a reciprocal relationship between emotion and physical activity. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Impact of WPABPs on Employees’ Physical and Mental Health

4.2. WPABPs and Work-Related Outcomes

4.3. Differential Impact of Individual vs. Group Interventions

4.4. The Value of WPABPs Within the ESG-S Framework

4.5. Intervention Heterogeneity and Future Implementation Challenges

4.6. Workplace Accessibility and Equity Issues

4.7. Disparities in Participation: Socioeconomic and Occupational Gaps in WPABP Research

5. Theoretical Implications

5.1. WPABPs as Environmental Stimuli in Sustainable Work Environments

5.2. Psychological Processes as Organismic Mediators

5.3. Behavioral and Attitudinal Responses as Sustainability Outcomes

5.4. Differentiation Between Individual and Group Pathways

5.5. Embedding S–O–R in the ESG-S and Sustainable HRM Context

5.6. Toward a Multi-Level S–O–R Perspective

5.7. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WPABPs | Workplace Physical Activity-Based Programs |

| S–O–R | Stimulus–Organism–Response |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, Governance |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being SDG 5: Gender Equality SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease-2019 |

| BPO | Business Process Outsourcing |

| SMEs | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| OHS | Occupational Health and Safety |

References

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2024: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, R.M. SDG3 Good Health and Well-Being: Integration and Connection with Other SDGs. In Good Health and Well-Being; Leal Filho, W., Wall, T., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 629–636. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, A.M.; Reed, R.; Sansone, J.; Batrakoulis, A.; McAvoy, C.; Parrott, M.W. 2024 ACSM Worldwide Fitness Trends: Future Directions of the Health and Fitness Industry. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 2024, 28, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, N.M.; Batrakoulis, A.; Camhi, S.M.; McAvoy, C.; Jessica, S.S.; Reed, R. 2025 ACSM Worldwide Fitness Trends: Future Directions of the Health and Fitness Industry. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 2024, 28, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoleaga, E.; Ahumada, M.; Soto-Contreras, E.; Vera, J. Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancman, S.; de Campos Bicudo, S.P.B.; da Silva Rodrigues, D.; de Fatima Zanoni Nogueira, L.; de Oliveira Barros, J.; de Lima Barroso, B.I. Mental Health and Work: A Systematic Review of the Concept. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, A.; Stassen, G.; Baulig, L.; Lange, M. Physical activity interventions in workplace health promotion: Objectives, related outcomes, and consideration of the setting—A scoping review of reviews. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1353119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, A.; Lüdemann, J.; Neuhausen, A.; Zepp, C.; Vitinius, F.; Kleinert, J. A Systematic Review of Workplace Physical Activity Coaching. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 33, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani, M.; Tayefi, B.; Zandian, E.; SoleimanvandiAzar, N.; Khalili, N.; Hoveidamanesh, S.; Massahikhaleghi, P.; Rampisheh, Z. Workplace interventions for increasing physical activity in employees: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health 2022, 64, e12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.N.d.; Gontijo, L.A.; Vieira, E.M.d.A.; Leite, W.K.d.S.; Colaço, G.A.; Carvalho, V.D.H.d.; Souza, E.L.d.; Silva, L.B.d. A worksite physical activity program and its association with biopsychosocial factors: An intervention study in a footwear factory. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 69, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ferguson, T.; Deev, A.; Deev, A.; Maher, C.A. Evaluation of the “15 Minute Challenge”: A Workplace Health and Wellbeing Program. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.; Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Get Active? A Meta-Analysis of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Hasson, H. Employee self-rated productivity and objective organizational production levels: Effects of worksite health interventions involving reduced work hours and physical exercise. J. Occup. Env. Med. 2011, 53, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R. The Impact of Employees’ Health and Well-being on Job Performance. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 29, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Park, T.-Y.; Kim, E. A resource-based perspective on human capital losses, HRM investments, and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-suraihi, W.; Siti, A.; Al-Suraihi, A.; Ibrahim, I.; Samikon; Al-Suraihi, A.-H.; Ibrhim, I.; Samikon, S. Employee Turnover: Causes, Importance and Retention Strategies. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirathananuwat, A.; Pongpirul, K. Promoting physical activity in the workplace: A systematic meta-review. J. Occup. Health 2017, 59, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Farrona, M.; Wipfli, B.; Thosar, S.S.; Colino, E.; Garcia-Unanue, J.; Gallardo, L.; Felipe, J.L.; López-Fernández, J. Effectiveness of worksite wellness programs based on physical activity to improve workers’ health and productivity: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martland, R.N.; Ma, R.; Paleri, V.; Valmaggia, L.; Riches, S.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B. The efficacy of physical activity to improve the mental wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 26, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larisch, L.M.; Kallings, L.V.; Thedin Jakobsson, B.; Blom, V. “It depends on the boss”-a qualitative study of multi-level interventions aiming at office workers’ movement behaviour and mental health. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2258564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waas, B. The “S” in ESG and international labour standards. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, A.; Robinot, E.; Trespeuch, L. The use of ESG scores in academic literature: A systematic literature review. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumewang, Y.K.; Ayunda, K.P.; Azzahra, M.R.; Hassan, M.K. The effects of diversity and inclusion on ESG performance: A comparison between Islamic and conventional banks. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Wang, W.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.W. Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Tu, S. An Empirical Study on Corporate ESG Behavior and Employee Satisfaction: A Moderating Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Xie, J.; Managi, S. Environmental, social, and corporate governance activities with employee psychological well-being improvement. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; p. xii, 266. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, İ.; Seçilmiş, C.; Kılıç, Ö.; Özhasar, Y. Do Green Hotels Lead Employees to Green Behavior? Application of Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory and Organismic-Integration-Theory. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, N.; Supriadi, A.; Ardiani, G.; Komarlina, D. Enhancing Worker Productivity through the S-O-R Theory in Human Resource Management. J. Manaj. Teor. Dan. Terap. J. Theory Appl. Manag. 2025, 18, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Z.; Saydan, R.; Kabak, A. Examining Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction in the Context of the S-O-R Model. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Frontiers in Academic Research, Konya, Turkey, 15–16 June 2024; pp. 500–508. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, L.; Li, J.X.; Liu, J. How Smart Technology Affects the Well-Being and Supportive Learning Performance of Logistics Employees? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 768440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Warkentin, M.; Wu, L. Understanding employees’ energy saving behavior from the perspective of stimulus-organism-responses. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.; Fong-Jia, W.; Chih-Fu, C.; Kuo-Feng, T. Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Creative Behavior and Turnover Intention in Professional Team Sports Organizations: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being. Sports Exerc. Res. 2024, 26, 138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. Faseb J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Sánchez, J.; Borrego-Balsalobre, F.J.; Díaz-Suárez, A.; Morales-Baños, V. Sports and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review of Their Contribution to the SDGs and Public Health. Sustainability 2025, 17, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M.A. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell University Library, C. Risk of Bias Assessment. Available online: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Brailovskaia, J.; Siegel, J.; Precht, L.-M.; Friedrichs, S.; Schillack, H.; Margraf, J. Less smartphone and more physical activity for a better work satisfaction, motivation, work-life balance, and mental health: An experimental intervention study. Acta Psychol. 2024, 250, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Sharp, C. Impacts of a workplace physical activity intervention on employee physical activity & mental health for NHS staff in Wales: An evaluation of the pilot Time to Move initiative. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2022, 7, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatesta, L.; Palermi, S.; Sirico, F.; Mancinelli, M.; Torelli, P.; Russo, E.; Annarumma, G.; Vecchiato, M.; Fernando, F.; Gregori, G.; et al. Short-term economic evaluation of physical activity-based corporate health programs: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health 2024, 66, uiae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msuya, M.S.; Kumar, A.B. Nexus between workplace health and employee wellness programs and employee performance. A Glob. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 5, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Munuo, G. Physical Activity at Work and Job Performance: A Qualitative Study of Physical Activity at Work from the Perspective of Office Workers in Tanzania. Master’s Thesis, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Candelario, C.M.C.; Fullante, M.K.A.; Pan, W.K.M.; Gregorio, E.R. Integrative Review of Workplace Health Promotion in the Business Process Outsourcing Industry: Focus on the Philippines. Public Health Pract. 2024, 7, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramashiva, P.S.; Annapoorna, K.; Vaishali, K.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Shivashankar, K.N.; Sukumar, S.; Ravichandran, S.; Shettigar, D.; Muthu, S.S.; Kamath, K.; et al. Enhancing well-being at work: Qualitative insights into challenges and benefits of long-term yoga programs for desk-based workers. Adv. Integr. Med. 2025, 12, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Pelletier, L.G.; Rocchi, M.; Neiva, H.P.; Teixeira, D.S.; Cid, L.; Silva, L.; Monteiro, D. Trainer-exerciser relationship: The congruency effect on exerciser psychological needs using response surface analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimiro-Andújar, A.J.; Martín-Moya, R.; Maravé-Vivas, M.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Effects of a Personalised Physical Exercise Program on University Workers Overall Well-Being: “UAL-Activa” Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Beltrán, E.; Coo, C.; Meneghel, I.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M. How physical exercise with others and prioritizing positivity contribute to (work) wellbeing: A cross-sectional and diary multilevel study. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1437974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Beltrán, E.; Meneghel, I.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M. Get vigorous with physical exercise and improve your well-being at work! Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, V.M.L. The importance of workplace exercise. Rev. Bras. De. Med. Do Trab. 2021, 19, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reicherzer, L.; Kramer-Gmeiner, F.; Labudek, S.; Jansen, C.-P.; Nerz, C.; Nystrand, M.J.; Becker, C.; Clemson, L.; Schwenk, M. Group or individual lifestyle-integrated functional exercise (LiFE)? A qualitative analysis of acceptability. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Lewis, C.; Cuy-Castellanos, D.; Byrd, A.; Zynda, K.; Sample, A.; Blakely Reed, V.; Beard, M.; Minor, L.; Yadrick, K. Using mixed methods to measure the perception of community capacity in an academic-community partnership for a walking intervention. Health Promot. Pr. 2012, 13, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candio, P. The effect of ESG and CSR attitude on financial performance in Europe: A quantitative re-examination. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalanka, S.; Ranjan, W.; Vitharana, S.; Abeysinghe, C. A Review of Barriers and Challenges Faced by Sports Entrepreneurs. J. Phys. Educ. Sports Stud. 2021, 4, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Lai, Y.-L.; Xu, X.; McDowall, A. The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of contemporary psychologically informed coaching approaches. J. Work-Appl. Manag. 2021, 14, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.T.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; Rudd, J. From a Technology That Replaces Human Perception-Action to One That Expands It: Some Critiques of Current Technology Use in Sport. Sports Med. Open 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, U.; Lanoix, M.; Gewurtz, R.; Moll, S.; Durocher, E. Vulnerability: An Interpretive Descriptive Study of Personal Support Workers’ Experiences of Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.-C.; Hong, Y.-R.; Wu, K.-N.; Chueh, T.-Y. A narrative literature review on the effects of physical activity interventions on executive function in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Q. Chin. Phys. Educ. 2025, 39, 303–319. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Title | Stimuli | Organism | Response | Operationalization of Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kılıç et al. (2025) [30] | Do Green Hotels Lead Employees to Green Behavior? Application of Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory and Organismic-Integration-Theory | Green hotel practices (e.g., green policies, eco-friendly operations). | Employees’ internal psychological states regarding environmental values and motivation. | Green behaviors performed by employees in the workplace. | Stimuli measured through green hotel practice scales; organism via environmental motivation and internalization constructs; responses via employee green behavior scales. |

| Taufik et al. (2025) [31] | Enhancing Worker Productivity through the S–O–R Theory in Human Resource Management | HRM-related stimuli such as rewards, leadership, and work environment. | Employees’ psychological reactions, including motivation and job attitudes. | Worker productivity and performance outcomes. | Stimuli operationalized through HRM practice indicators; organism via motivation/attitude scales; responses via productivity self-report and supervisor ratings. |

| Çelik et al. (2024) [32] | Examining Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction in the Context of the S–O–R Model | Workplace conditions and job-related stimuli (e.g., work environment, organizational policies). | Employees’ internal evaluations of job satisfaction and life satisfaction. | Behavioral and attitudinal outcomes linked to satisfaction levels. | Workplace stimuli measured via organizational climate scales; organism via job satisfaction and life satisfaction scales; responses via behavioral intention measures. |

| Jiang et al. (2022) [33] | How Smart Technology Affects the Well-Being and Supportive Learning Performance of Logistics Employees? | Stimuli derived from smart technology use and digital systems in logistics workplaces. | Psychological well-being, perceived support, and cognitive-emotional states of employees. | Supportive learning performance and employee outcomes. | Smart technology stimuli measured through technology acceptance/usage scales; organism via well-being and perceived support metrics; responses via learning performance indicators. |

| Tang et al. (2019) [34] | Understanding employees’ energy saving behavior from the perspective of stimulus-organism-responses | Organizational energy-saving cues, policies, and environmental prompts. | Employees’ internal cognitive states such as environmental concern and perceived responsibility. | Energy-saving behavior at work. | Stimuli assessed using organizational energy policy and cue scales; organism via environmental cognition and responsibility constructs; responses via self-reported energy-saving behaviors. |

| Chung et al. (2024) [35] | Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Creative Behavior and Turnover Intention in Professional Team Sports Organizations: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being | Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives perceived by employees. | Employees’ subjective well-being as an internal psychological state. | Creative behavior and turnover intention. | CSR stimuli measured through CSR perception scales; organism via subjective well-being scales; responses via creative behavior and turnover intention scales. |

| Keywords | |

|---|---|

| MeSH Entry Term (Equivalent/Synonymous) | MeSH Preferred Term |

| workplace/worksite | workplace |

| employees/workers | personnel/occupational groups |

| physical activity | exercise |

| wellness program/health Programs | health promotion |

| well-being/mental health | mental health |

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Employees working in organizational or occupational settings across sectors | Non-employees (e.g., students, unemployed individuals, or non-workplace-related) |

| Intervention | Interventions involving any form of occupational health promotion | Interventions unrelated to occupational health promotion |

| Comparator | Studies including a control, comparison, or pre-post design examining the effects of workplace exercise interventions | Studies lacking a comparison group or not assessing the effects of exercise interventions |

| Outcome | Studies reporting measurable or reported outcomes related to physical and mental health, or work-related outcomes | Studies not reporting measurable or relevant health or work-related outcomes |

| Study design | Clearly described methodology; original research articles, RCTs, observational studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, quasi-experimental studies, narrative reviews | Unclear methodology; experimental abstracts, case reports, editorials, letters to the editor |

| Other | Non-duplicate records; full-text articles availability; English-language publications; published within the past five years | Duplicate records; articles without full text; non-English-language publications; published more than five years ago |

| Database | ScienceDirect | PubMed | Scopus | Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected Articles | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| Total Articles | 15 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.Y.; Fang, C.Y. Sustainable Workplaces and Employee Well-Being: A Systematic Review of ESG-Linked Physical Activity Programs. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233146

Chen HY, Fang CY. Sustainable Workplaces and Employee Well-Being: A Systematic Review of ESG-Linked Physical Activity Programs. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233146

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hsuan Yu (Julie), and Chin Yi (Fred) Fang. 2025. "Sustainable Workplaces and Employee Well-Being: A Systematic Review of ESG-Linked Physical Activity Programs" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233146

APA StyleChen, H. Y., & Fang, C. Y. (2025). Sustainable Workplaces and Employee Well-Being: A Systematic Review of ESG-Linked Physical Activity Programs. Healthcare, 13(23), 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233146