Assessment of Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Mental Health Status Among Syrian Refugee Mothers with Young Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements and Diet Quality

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

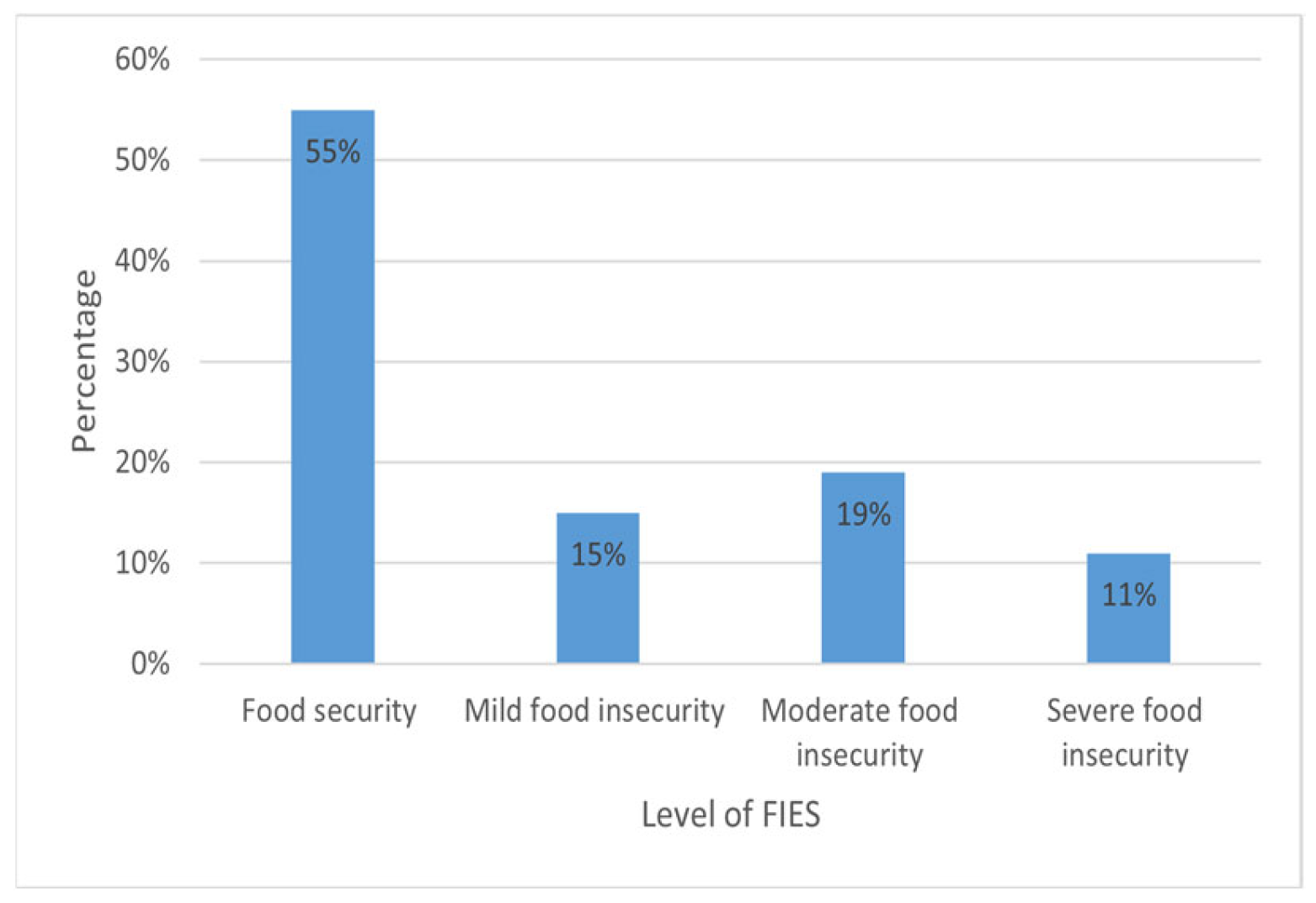

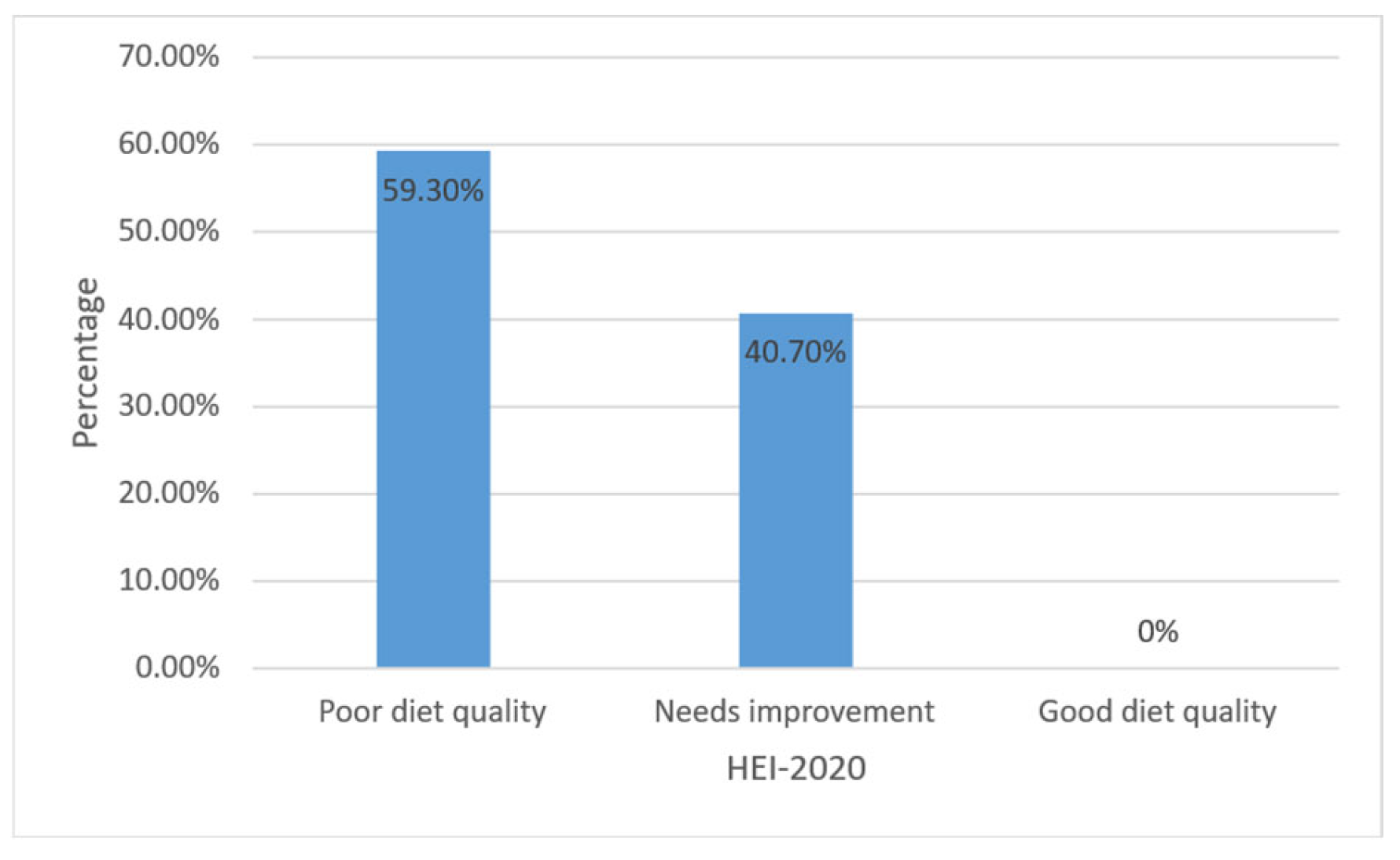

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FIES | Food Insecurity Experience Scale |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| HEI-2020 | Healthy-Eating Index-2020 |

References

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household food security in the United States in 2018; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/301167 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Resilience, B. The State of food security and nutrition in the world. In Building Resilience for Peace and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO FIUW. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024. In The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bazz, S.; Al-Kharabsheh, L.; Béland, D.; Lane, G.; Engler-Stringer, R.; White, J.; Koc, M.; Batal, M.; Chevrier, J.; Vatanparast, H. Are residency and type of refugee settlement program associated with food (in) security among Syrian refugees who have resettled in Canada since 2015? Food Secur. 2024, 16, 1175–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisha, T.A. Household level food insecurity assessment: Evidence from panel data, Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 2020, 7, e00262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmcheshm, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Babashahi, M.; Sharegh Farid, E.; Dorosty, A.R. Socioeconomic determinants of food insecurity in Iran: A systematic review. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2024, 59, 1908–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazuma, E.G. An empirical examination of the determinants of food insecurity among rural farm households: Evidence from Kindo Didaye District of Southern Ethiopia. Bus. Econ. J. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getaneh, Y.; Alemu, A.; Ganewo, Z.; Haile, A. Food security status and determinants in North-Eastern rift valley of Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, O. The dynamics of household food insecurity in Turkey. Sosyoekonomi 2022, 30, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedullah, A.; Khan, M.S.; Andrews, S.C.; Iqbal, K.; Ul-Haq, Z.; Qadir, S.A.; Khan, H.; Iddrisu, I.; Shahzad, M. Nutritional Status of Adolescent Afghan Refugees Living in Peshawar, Pakistan. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Booth, A.; Margerison, C.; Worsley, A. What factors are associated with food security among recently arrived refugees resettling in high-income countries? A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4313–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamelkova, D.; Strømme, E.M.; Diaz, E. Food insecurity and its association with mental health among Syrian refugees resettled in Norway: A cross-sectional study. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejiohuo, O.; Onyeaka, H.; Unegbu, K.C.; Chikezie, O.G.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Lawal, A.; Odeyemi, O.A. Nourishing the mind: How food security influences mental wellbeing. Nutrients 2024, 16, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomaa, L.H.; Naja, F.A.; Kharroubi, S.A.; Diab-El-Harake, M.H.; Hwalla, N.C. Food insecurity is associated with compromised dietary intake and quality among Lebanese mothers: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Ker, S.; Archer, D.; Gilbody, S.; Peckham, E.; Hardman, C.A. Food insecurity and severe mental illness: Understanding the hidden problem and how to ask about food access during routine healthcare. BJPsych Adv. 2023, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantekin, D. Syrian refugees living on the edge: Policy and practice implications for mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Int. Migr. 2019, 57, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calia, C.; El-Gayar, A.; Zuntz, A.-C.; Abdullateef, S.; Almashhor, E.; Grant, L.; Boden, L. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Mental Health Among Syrians and Syrian Refugees Working in Agriculture During COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M.A.; Ricard, R.J. Meeting the mental health needs of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Prof. Couns. 2016, 6, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’zah, S.; Lopes Cardozo, B.; Evans, D.P. Mental health status and service assessment for adult Syrian refugees resettled in metropolitan Atlanta: A cross-sectional survey. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.; Ventevogel, P.; Jefee-Bahloul, H.; Barkil-Oteo, A.; Kirmayer, L.J. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 25, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmotabbed, A.; Moradi, S.; Babaei, A.; Ghavami, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Jalili, C.; Symonds, M.E.; Miraghajani, M. Food insecurity and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.; van Ommeren, M.; Flaxman, A.; Cornett, J.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, R.; Boyle, J.A.; Fazel, M.; Ranasinha, S.; Gray, K.M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Misso, M.; Gibson-Helm, M. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response. 2025. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/where-we-work/countries/republic-tuerkiye (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- UNHCR. Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Türkiye. 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/tr/en/refugees-and-asylum-seekers-in-turkey (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Esin, K.; Işık, T.; Ayyıldız, F.; Koc, M.; Vatanparast, H. Prevalence and risk factors of food insecurity among Syrian refugees in Türkiye. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarturk, C.; McGrath, M.; Roberts, B.; Ilkkursun, Z.; Cuijpers, P.; Sijbrandij, M.; Sondorp, E.; Ventevogel, P.; McKee, M.; Fuhr, D.C. Prevalence and predictors of common mental disorders among Syrian refugees in Istanbul, Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atayoglu, A.T.; Firat, Y.; Kaya, N.; Basmisirli, E.; Capar, A.G.; Aykemat, Y.; Atayolu, R.; Khan, H.; Guner Atayoglu, A.; Inanc, N. Evaluation of nutritional status with Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2010) of syrian refugees living outside the refugee camps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.; Andrade, L.; Packull-McCormick, S.; Perlman, C.M.; Leos-Toro, C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, L.; Tarasuk, V.; Li, T.J. Improving the nutritional status of food-insecure women: First, let them eat what they like. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. Off-Camp Syrian Refugees in Türkiye: A Food Security Report; WFP: Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weinmann, T.; AlZahmi, A.; Schneck, A.; Mancera Charry, J.F.; Fröschl, G.; Radon, K. Population-based assessment of health, healthcare utilisation, and specific needs of Syrian migrants in Germany: What is the best sampling method? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GİGM. Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior Presidency of Migration Management: Statictics, Temporary Protection. 2025. Available online: https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkiye/statistics (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Britannica Demography, Religion, and Politics in Türkiye. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Turkey (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Rizk, J.; Jeremias, T.; Cocuz, G.; Nasreddine, L.; Jomaa, L.; Hwalla, N.; Frank, J.; Scherbaum, V. Food insecurity, low dietary diversity and poor mental health among Syrian refugee mothers living in vulnerable areas of Greater Beirut, Lebanon. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1832–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, Y.E.; Kokoglu, B.; Balcioglu, H.; Bilge, U.; Colak, E.; Unluoglu, I. Turkish reliability of the patient health questionnaire-9. Biomed. Res. India 2016, 27, S460–S462. [Google Scholar]

- Zulkarnain Helmi, N.; Md Isa, K.A.; Masuri, M.G. Exploratory factor analysis on Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES): Latest food insecurity measurement tool by FAO. Health Scope 2020, 3, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, T.J.; Kepple, A.W.; Cafiero, C.; Schmidhuber, J. Better measurement of food insecurity in the context of enhancing nutrition. Ernahr. Umsch. 2014, 61, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero, C.; Viviani, S.; Nord, M. Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement 2018, 116, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Vargas-Fernández, R.; Visconti-Lopez, F.J.; Aparco, J.P. Prevalence and socioeconomic determinants of food insecurity among Venezuelan migrant and refugee urban households in Peru. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1187221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekcan, G. Beslenme durumunun saptanmasi. Diyet El Kitabi 2008, 726, 67–141. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, A.; Smith, S. Body composition and morphological assessment of nutritional status in adults: A review of anthropometric variables. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health, NIo. Clinical guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults-the evidence report. Obes. Res. 1998, 6, 51S–209S. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. In Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rakıcıoğlu, N.; Tek, N.; Ayaz, A.; Pekcan, A. Yemek ve Besin Fotoğraf Kataloğu Ölçü ve Miktarlar; Ata Ofset Matbaacılık: İstanbul, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams-White, M.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Lerman, J.L.; Herrick, K.A.; Zimmer, M.; Meyers Mathieu, K.; Stoody, E.E.; Reedy, J. Healthy Eating Index-2020: Review and Update Process to Reflect the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverding, M.; Jamaluddine, Z. Receipt of humanitarian cash transfers, household food insecurity and the subjective wellbeing of Syrian refugee youth in Jordan. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 28, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabulsi, D.; Ismail, H.; Abou Hassan, F.; Sacca, L.; Honein-AbouHaidar, G.; Jomaa, L. Voices of the vulnerable: Exploring the livelihood strategies, coping mechanisms and their impact on food insecurity, health and access to health care among Syrian refugees in the Beqaa region of Lebanon. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, R.; Coccia, C.; George, F.; Huffman, F. The Impact of Employment Status and Children in Households on Food Security Among Syrian Refugees Residing in Florida. Cureus 2025, 17, e78751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazal, A.; Bozoğlu, M. Determinants of the food expenditure of the refugee households in Samsun province of Turkey. Anadolu Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2022, 37, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.; Liamputtong, P.; Arora, A. Prevalence, determinants, and effects of food insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African migrants and refugees in high-income countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharabsheh, L.; Al-Bazz, S.; Koc, M.; Garcia, J.; Lane, G.; Engler-Stringer, R.; White, J.; Vatanparast, H. Household food insecurity and associated socio-economic factors among recent Syrian refugees in two Canadian cities. Bord. Crossing 2020, 10, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Correia, D.; Torres, D.; Lopes, C. Food insecurity and social determinants of health among immigrants and natives in Portugal. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, D.; Sanou, D.; Blanchet, R.; Nana, C.P.; Batal, M.; Giroux, I. Prevalence and determinants of food insecurity in migrant Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean households in Ottawa, Canada. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2018, 14, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, A.; Skuterud, M. Explaining the deteriorating entry earnings of Canada’s immigrant cohorts, 1966–2000. Can. J. Econ./Rev. Can. D’économique 2005, 38, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, M.; Morissette, R. Will They Ever Converge? Earnings of Immigrant and Canadian-born Workers over the Last Two Decades 1. Int. Migr. Rev. 2005, 39, 228–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddine, Z.; Irani, A.; Moussa, W.; Al Mokdad, R.; Chaaban, J.; Salti, N.; Ghattas, H. The impact of dosage variability of multi-purpose cash assistance on food security in Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa053_051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Hurley, K.M.; Ruel-Bergeron, J.; Monclus, A.B.; Oemcke, R.; Wu, L.S.F.; Mitra, M.; Phuka, J.; Klemm, R.; West, K.P., Jr. Household food insecurity is associated with low dietary diversity among pregnant and lactating women in rural Malawi. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.R.; Ghimire, S.; Upadhayay, S.R.; Singh, S.; Ghimire, U. Food insecurity and dietary diversity among lactating mothers in the urban municipality in the mountains of Nepal. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwalla, N.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Radwan, H.; Alfawaz, H.A.; Fouda, M.A.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Zaghloul, S.; Blumberg, J.B. The prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies and inadequacies in the Middle East and approaches to interventions. Nutrients 2017, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Escamilla, R.; Bermudez, O.; Buccini, G.S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Monsivais, P.; Victora, C. Nutrition disparities and the global burden of malnutrition. BMJ 2018, 361, k2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Anderson, C.; Kaufer-Horwitz, M.; Bode, L.; Emenaker, N.J.; Haqq, A.M.; Satia, J.A.; Silver, H.J.; Stadler, D.D. Poverty, obesity, and malnutrition: An international perspective recognizing the paradox. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, B.; Tang, S.; Yaya, S.; Feng, Z. Association between food insecurity and anemia among women of reproductive age. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerfu, T.A.; Umeta, M.; Baye, K. Dietary diversity during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of maternal anemia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in a prospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Thaver, I.; Khan, S.A. Assessment of dietary diversity and nutritional status of pregnant women in Islamabad, Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2014, 26, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ae-Ngibise, K.A.; Asare-Doku, W.; Peprah, J.; Mujtaba, M.N.; Nifasha, D.; Donnir, G.M. The mental health outcomes of food insecurity and insufficiency in West Africa: A systematic narrative review. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henjum, S.; Caswell, B.L.; Terragni, L. “I Feel like I’m Eating Rice 24 Hours a Day, 7 Days a Week”: Dietary Diversity among Asylum Seekers Living in Norway. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodorescu, D.S.; Heir, T.; Hauff, E.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Lien, L. Mental health problems and post-migration stress among multi-traumatized refugees attending outpatient clinics upon resettlement to Norway. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Food Secure (n = 198) | Food Insecure (n: 87) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 29.20 ± 6.11 | 29.48 ± 6.54 | 0.727 |

| HSA score (X ± SD) | 9.88 ± 4.37 | 13.74 ± 5.34 | <0.001 * |

| HEI score (X ± SD) | 50.98 ± 11.43 | 47.89 ± 8.88 | 0.014 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) (X ± SD) | 26.04 ± 5.75 | 26.54 ± 50.8 | 0.927 |

| Waist circumference (cm) (X ± SD) | 82.48 ± 9.38 | 83.17 ± 10.57 | 0.600 |

| Waist/Hip (X ± SD ) | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.102 |

| Mother’s education level | |||

| Illiterate | 12 (5.7%) | 15 (20.0%) | 0.001 ** |

| Literate | 38 (18.1%) | 12 (16.0%) | |

| Primary school | 115 (54.8%) | 40 (53.3%) | |

| High school | 45 (21.4%) | 8 (10.7%) | |

| Duration of stay (years) | |||

| 5–7 years | 20 (9.5%) | 36 (48.0%) | <0.001 ** |

| 8–10 years | 120 (57.1%) | 26 (34.7%) | |

| 11–13 years | 70 (33.3%) | 13 (17.3%) | |

| Number of children | |||

| 1–2 | 75 (35.7%) | 27 (36.0%) | 0.828 |

| 3–4 | 80 (38.1%) | 26 (34.7%) | |

| ≥5 | 55 (26.2%) | 22 (29.3%) | |

| Income status | |||

| Equals expenses | 95 (45.2%) | 32 (42.7%) | 0.803 |

| Less than expenses | 115 (54.8%) | 43 (57.3%) | |

| Receiving food assistance | |||

| Yes | 125 (59.5%) | 37 (49.3%) | 0.163 |

| No | 85 (40.5%) | 38 (50.7%) | |

| Anemia status | |||

| Anemic | 60 (28.6%) | 35 (46.7%) | 0.007 ** |

| Not anemic | 150 (71.4%) | 40 (53.3%) |

| Model | Food Insecure Score | İncome Status | Time Duration | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | B | 1.031 | 0.302 | ||

| SE | 0.093 | ||||

| β | 0.552 | ||||

| t | 11.128 * | ||||

| Model 2 | B | 1 | 2.075 | 0.339 | |

| SE | 0.09 | 0.505 | |||

| β | 0.535 | 0.199 | |||

| t | 11.055 * | 4.110 * | |||

| Model 3 | B | 0.729 | 2.098 | −0.531 | 0.367 |

| SE | 0.115 | 0.494 | 0.144 | ||

| β | 0.39 | 0.201 | −0.227 | ||

| t | 6.344 * | 4.246 * | −3.695 * |

| Variable | Needs Improvement | Poor Diet | OR (95% CI) | p * | aOR (95% CI) | p ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n: 116) | (n: 169) | |||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 10 (8.6) | 17 (10.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Literate | 19 (16.4) | 31 (18.3) | 0.96 (0.36–2.52) | 0.934 | 1.78 (0.60–5.25) | 0.299 |

| Primary school | 60 (51.7) | 95 (56.2) | 0.93 (0.40–2.16) | 0.869 | 1.99 (0.76–5.24) | 0.160 |

| High school | 27 (23.3) | 26 (15.4) | 0.56 (0.21–1.46) | 0.24 | 1.45 (0.48–4.35) | 0.501 |

| İncome status | ||||||

| Equal | 61 (52.6) | 66 (39.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low | 55 (47.4) | 103 (60.9) | 1.73 (1.07–2.79) | 0.024 | 1.71 (1.01–2.89) | 0.048 |

| Receiving food assistance | ||||||

| Yes | ||||||

| No | 76 (65.5) | 86 (50.9) | 1 | 0.015 | 1 | 0.001 |

| 40 (34.5) | 83 (49.1) | 1.83 (1.12–2.98) | 3.15 (1.56–6.37) | |||

| Time spent living in Türkiye | ||||||

| 5–7 years | 10 (8.6) | 46 (27.2) | 8.12 (3.58–18.40) | <0.001 | 6.75 (2.81–16.18) | <0.001 |

| 8–10 years | 53 (45.7) | 93 (55.0) | 3.10 (1.77–5.43) | <0.001 | 2.70 (1.48–4.91) | 0.001 |

| 11–13 years | 53 (45.7) | 30 (17.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Number of children | ||||||

| 1–2 | 49 (42.2) | 53 (31.4) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3–4 | 48 (41.4) | 58 (34.3) | 1.12 (0.65–1.93) | 0.69 | 2.31 (1.10–4.81) | 0.026 |

| ≥5 | 19 (16.4) | 58 (34.3) | 2.82 (1.48–5.39) | 0.02 | 5.90 (2.47–14.05) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coşkunsu, S.; Yılmaz, M. Assessment of Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Mental Health Status Among Syrian Refugee Mothers with Young Children. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233083

Coşkunsu S, Yılmaz M. Assessment of Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Mental Health Status Among Syrian Refugee Mothers with Young Children. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233083

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoşkunsu, Sedat, and Müge Yılmaz. 2025. "Assessment of Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Mental Health Status Among Syrian Refugee Mothers with Young Children" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233083

APA StyleCoşkunsu, S., & Yılmaz, M. (2025). Assessment of Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Mental Health Status Among Syrian Refugee Mothers with Young Children. Healthcare, 13(23), 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233083