Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss Among Providers and Patients: A Scoping Review

Highlights

- Limited evidence exists examining knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding diabetes-related hearing loss, with only a few studies identified from four countries, focusing predominantly on healthcare providers with minimal patient data.

- Knowledge of diabetes-related hearing loss was substantially lower among both providers and patients compared to other complications, reflected in poor screening attitudes, minimal practices and counseling, and hearing screening rates.

- Systematic integration of hearing evaluations into diabetes care pathways offers potential for improved patient outcomes and reduced undiagnosed complications, though implementation strategies require further investigation.

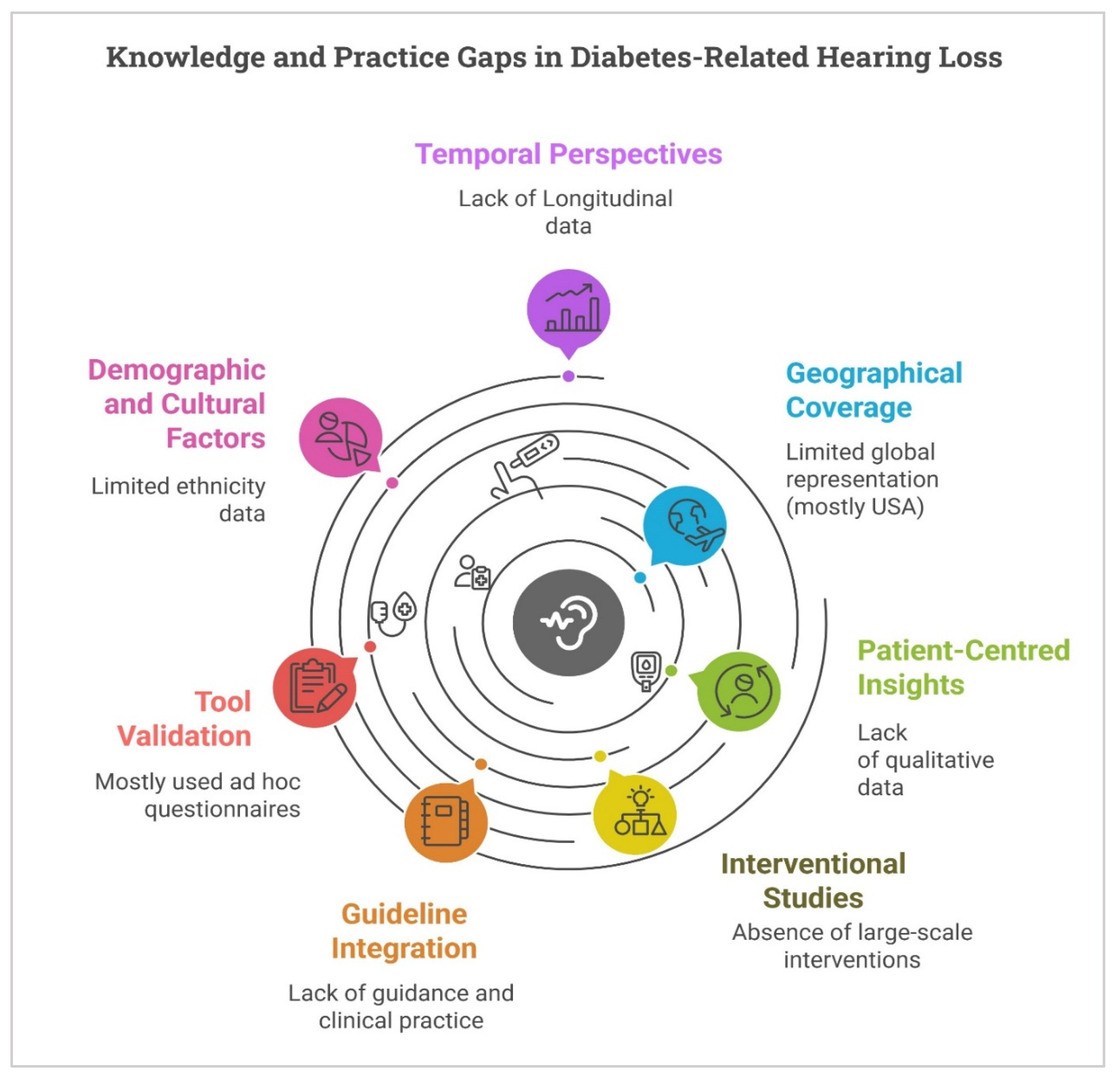

- Future research should prioritise standardised KAP assessment instruments, large-scale educational intervention studies across diverse settings, qualitative investigations of patient and provider perspectives, and cost-effectiveness analyses to inform policy development.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection

- Population: Healthcare providers, including general practitioners, endocrinologists, diabetologists, diabetes educators, and other diabetes care specialists; audiologists; and patients diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Concept: Knowledge, awareness, attitudes, or practices concerning diabetes-associated hearing loss and its management.

- Context: Primary research studies employing quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods designs; reports; theses; and policy documents published in English from 2000 onwards.

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Charting the Data

2.6. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

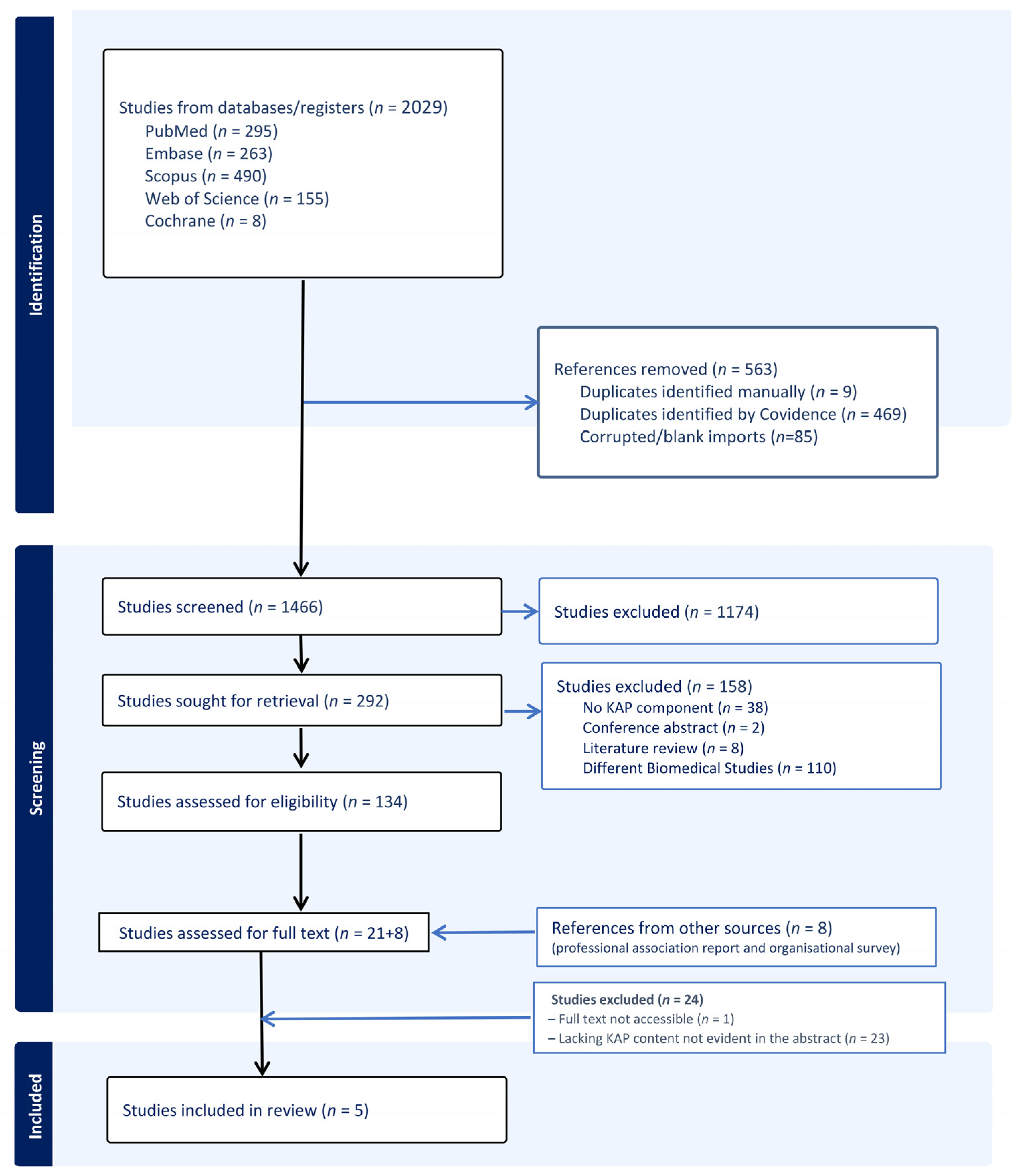

3.1. Screening Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Instruments and Methods Used to Assess KAP

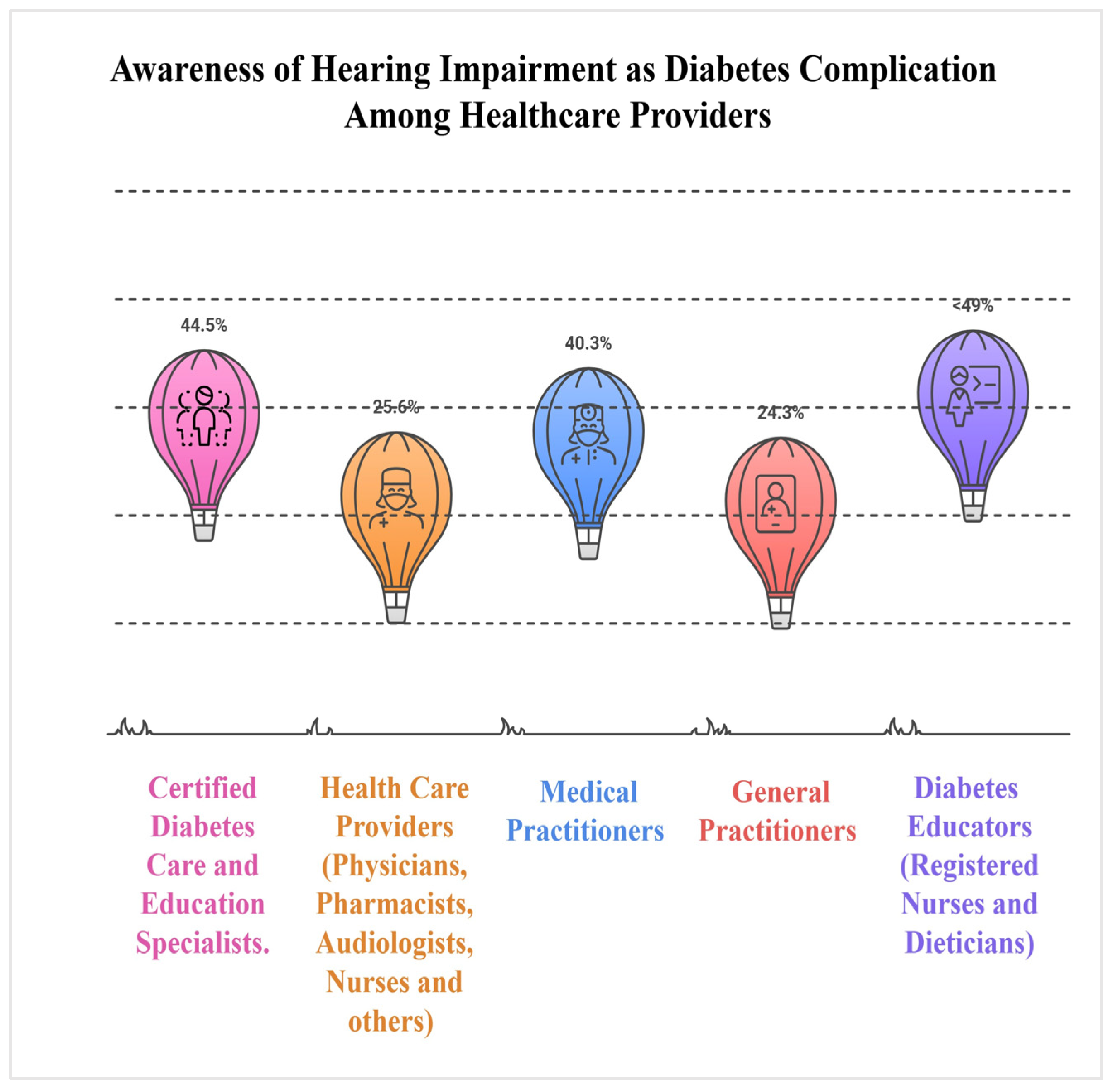

3.4. Knowledge and Awareness of Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss

3.5. Attitudes and Perceptions Regarding Hearing Loss in Diabetes Care

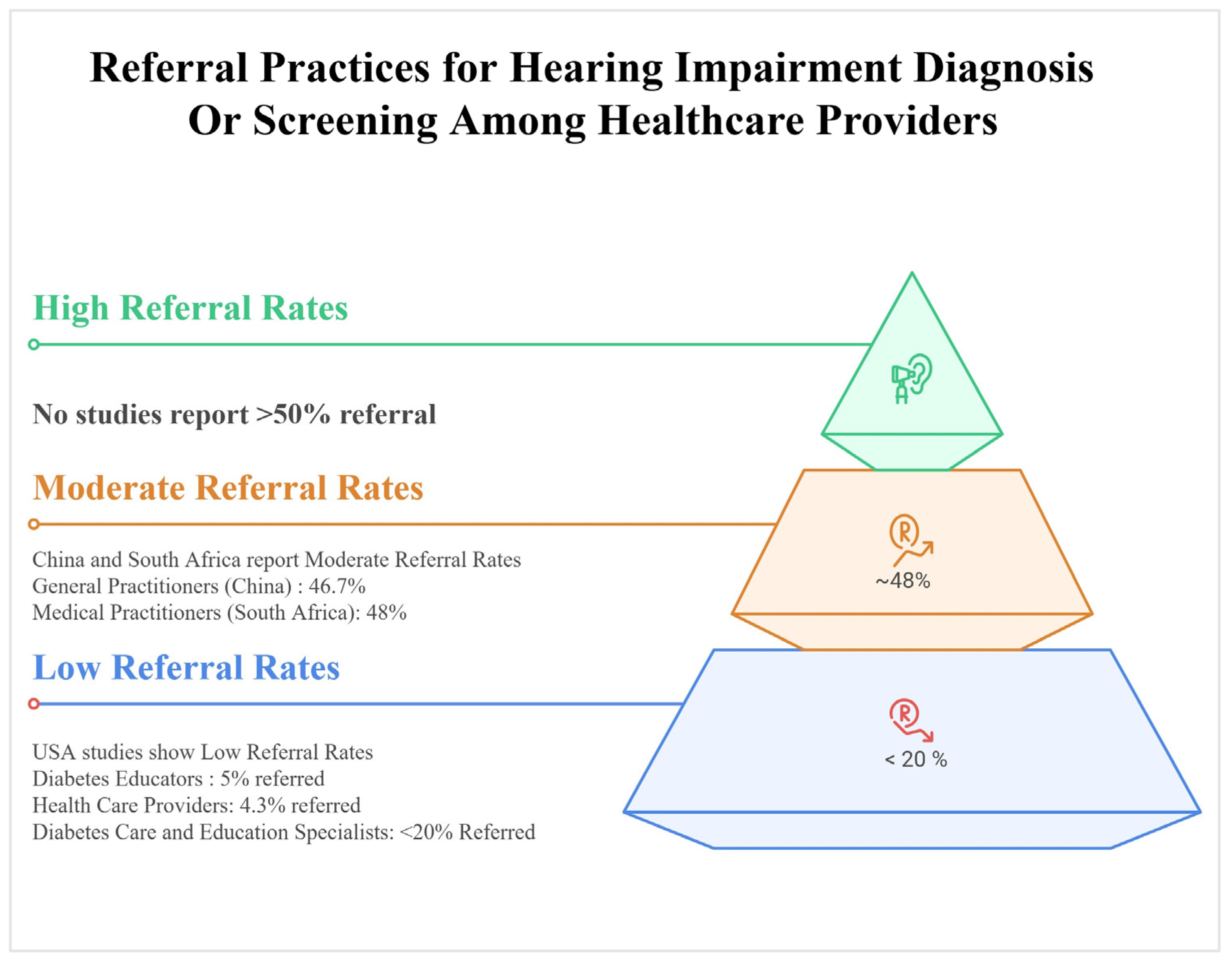

3.6. Practices: Screening and Referral

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

Implications and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IDF. The Diabetes Atlas. 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/#:~:text=589%20million%20adults (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zou, W.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Ye, H.; Huang, W. Global, regional, and national burden of hearing loss from 1990 to 2021: Findings from the 2021 global burden of disease study. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2527367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H.S.; Lauritsen, K.L.; Nguyen, S.A.; Meyer, T.A.; Cumpston, E.C.; Pelic, J.; Labadie, R. Characteristics of Hearing Loss in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.M.; Jacob, J.J.; Varghese, A. Prevalence of Hearing Loss in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Association with Severity of Diabetic Neuropathy and Glycemic Control. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2023, 71, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, K.E.; Hoffman, H.J.; Cowie, C.C. Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: Audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, S.; Hu, J. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Keith, G.; Lacey, M.; Lemos, J.R.N.; Mittal, J.; Assayed, A.; Hirani, K. Diabetes mellitus, hearing loss, and therapeutic interventions: A systematic review of insights from preclinical animal models. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutt, P.A.; Barnier, A.J.; Savage, G.; Picard, G.; Kochan, N.A.; Sachdev, P.; Draper, B.; Brodaty, H. Hearing loss, cognition, and risk of neurocognitive disorder: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study of older adult Australians. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2022, 29, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R.; Hong, O.; I Wallhagen, M. The contribution of ototoxic medications to hearing loss among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spankovich, C.; Yerraguntla, K. Evaluation and management of patients with diabetes and hearing loss. In Seminars in Hearing; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, S.; Ali, Z.; Abdullah, A.; Naveed, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Rafi, T.S.M. Sensorineural hearing loss among type 2 diabetic patients and its association with peripheral neuropathy: A cross-sectional study from a lower middle-income country. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e081035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, M.; Dawes, P. Diabetes and hearing loss: A call to action for early detection and prevention. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2025, 54, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnakota, D. Mastering the art of scoping reviews: A comprehensive guide for public health and allied health students. Asian J. Public Health Nurs. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelnicek, T.D.; Sewell, H.E.; Planas, L.G.; Skaggs, J.C.; Lim, J.; Johnson, C.E.; O’nEal, K.S. Assessing Current Knowledge of Hearing Impairment with Diabetes by Surveying Providers with CBDCE Certification. Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care 2025, 51, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, H.E.; Planas, L.G.; Brown, M.R.; Orcutt, N.; Johnson, C.E.; Lim, J.; Skaggs, J.C.; O’nEal, K.S. Diabetes and hearing impairment: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among providers and patients. Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care 2024, 50, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, H.; Ren, G.; Sun, X.; Jiang, H. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice of General Practitioners Toward Screening of Age-Related Hearing Loss in Community: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shanghai, China. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinabhai, D.D. Hearing Health Awareness among Medical Practitioners Managing Patients with Diabetes in South Africa. In Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences; The University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd, K. Hearing Loss Awareness among Diabetes Educators. 2011. Available online: https://www.theaudiologyproject.com/s/Hearing-Loss-Awareness-Summary.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- CDC. Promoting Ear Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/hcp/clinical-guidance/how-to-promote-ear-health-for-people-with-diabetes.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kauffman, L. Diabetes and hearing loss. Hear. Rev. 2021, 28, 14–18. Available online: https://hearingreview.com/inside-hearing/research/diabetes-2 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Nkosi, S.T.; Peter, V.Z.; Paken, J. Audiological profile of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2024, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B. Interventional Audiology: Broadening the Scope of Practice to Meet the Changing Demands of the New Consumer. Semin. Hear. 2016, 37, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazove, P.; Plegue, M.A.; McKee, M.M.; DeJonckheere, M.; Kileny, P.R.; Schleicher, L.S.; Green, L.A.; Sen, A.; Rapai, M.E.; Mulhem, E. Effective Hearing Loss Screening in Primary Care: The Early Auditory Referral-Primary Care Study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2020, 18, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davine, E.C.; Busby, P.A.; Peters, S.; Francis, J.J.; Sarant, J.Z. Barriers and enablers to general practitioner referral of older adults to hearing care: A systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2025, 16, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, K. The Role of Audiology in the Care of Persons with Diabetes. Semin. Hear. 2019, 40, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana, T.I.; Jackson, C.A. Socioeconomic status and multimorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nisar, M.; Ahmed, M.W.N.; Rajagopal, A.; Ahmed, B.N.; Lassi, Z.S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss Among Providers and Patients: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233025

Nisar M, Ahmed MWN, Rajagopal A, Ahmed BN, Lassi ZS. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss Among Providers and Patients: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233025

Chicago/Turabian StyleNisar, Mehwish, Muhammad Waqas Nisar Ahmed, Anjana Rajagopal, Beenish Nisar Ahmed, and Zohra S. Lassi. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss Among Providers and Patients: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233025

APA StyleNisar, M., Ahmed, M. W. N., Rajagopal, A., Ahmed, B. N., & Lassi, Z. S. (2025). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Diabetes-Related Hearing Loss Among Providers and Patients: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(23), 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233025