Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction and Multidimensional Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Healthy Korean Older Adults: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

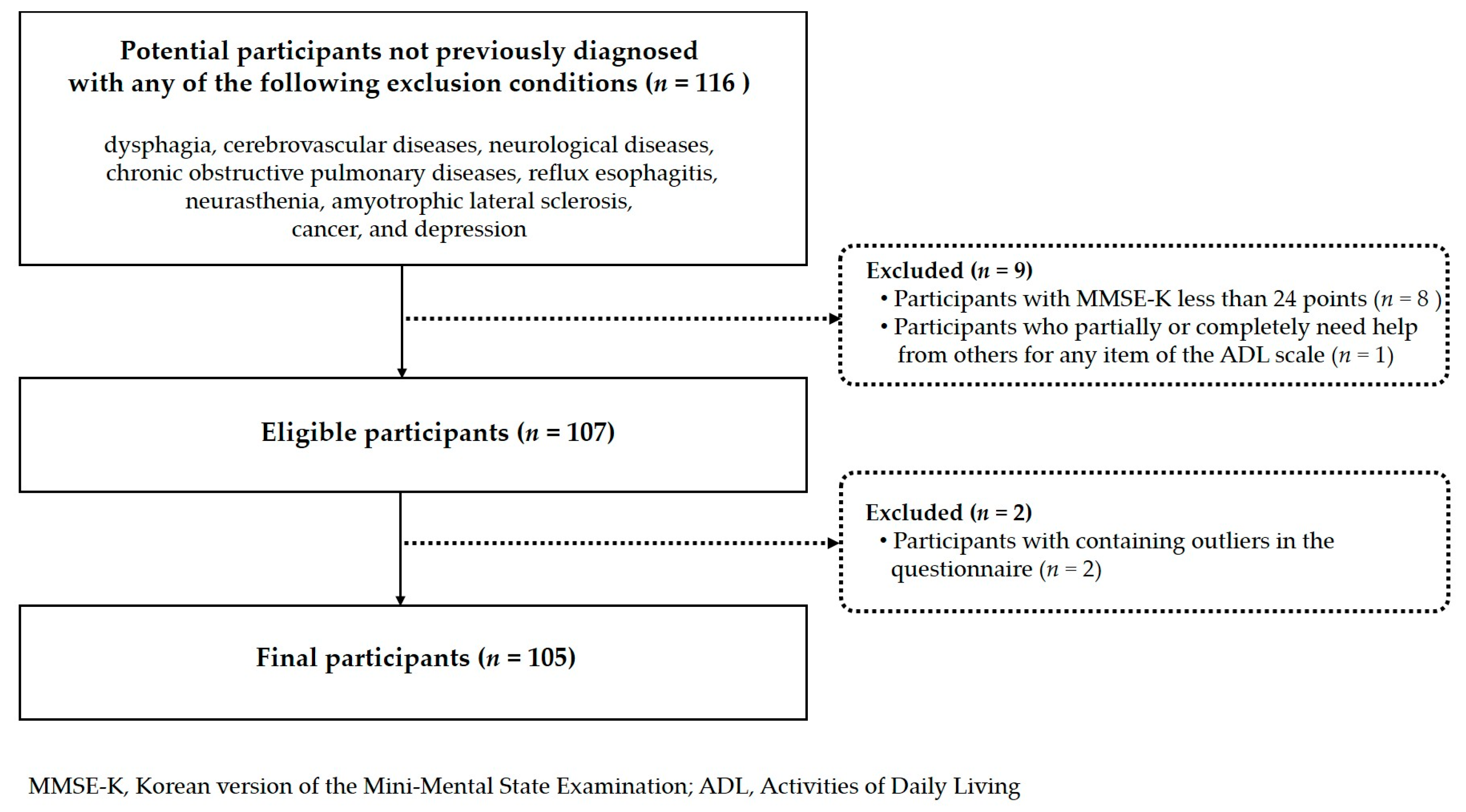

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quality of Life by Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Quality of Life by Health Behaviors

3.3. Quality of Life by Oral and General Health Status

3.4. Intensity of Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction Risk and Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MMSE-K | Mini-Mental State Examination-Korean version |

| ADL-K | Korean Activities of Daily Living |

| DRAS | Dysphagia Risk Assessment Scale |

| RSST | Repetitive Saliva Swallowing Test |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SD | standard deviation |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; UN Desa Pop, 2022/TR/NO.3; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Data and Statistics (Korea). 2025 Statistics on the Aged. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=10820&tag=&act=view&list_no=438832&ref_bid= (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazayeri, E.; Kazemipour, S.; Hosseini, S.R.; Radfar, M. Quality of life in the elderly: A community study. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 14, 534–542. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.J.; Kihl, T. Suicidal ideation associated with depression and social support: A survey-based analysis of older adults in South Korea. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussenoeder, F.S.; Jentzsch, D.; Matschinger, H.; Hinz, A.; Kilian, R.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Conrad, I. Depression and quality of life in old age: A closer look. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Khanal, P.; Shrestha, S.; Mohan, D.; Myint, P.K.; Su, T.T. Determinants of active aging and quality of life among older adults: Systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1193789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Programme on Mental Health: WHOQOL User Manual, 2012 Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya, M.G.; Bilgin, S.C.; Ekici, G.; Köse, N.; Otman, A.S. Functional mobility, depressive symptoms, level of independence, and quality of life of the elderly living at home and in the nursing home. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009, 10, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torvik, K.; Kaasa, S.; Kirkevold, O.; Rustøen, T. Pain and quality of life among residents of Norwegian nursing homes. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2010, 11, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.K.Y.; Leung, D.D.M.; Kwong, E.W.Y.; Lee, R.L.P. Factors associated with the quality of life of nursing home residents in Hong Kong. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, C.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. Oral Health and quality of life: Findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Korean Dysphagia Society. Swallowing Disorders, 1st ed.; Koonja Publishing: Paju-si, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Atanda, A.J.; Livinski, A.A.; London, S.D.; Boroumand, S.; Weatherspoon, D.; Iafolla, T.J.; Dye, B.A. Tooth retention, health, and quality of life in older adults: A scoping review. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Pei, Y.; Wang, K.; Han, S.; Wu, B. Social isolation, loneliness and accelerated tooth loss among Chinese older adults: A longitudinal study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2023, 51, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, N.; Stemple, J.; Merrill, R.M.; Thomas, L. Dysphagia in the elderly: Preliminary evidence of prevalence, risk factors, and socioemotional effects. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2007, 116, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmas, C.; Rogus-Pulia, N. Swallowing disorders in the older population. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2643–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, D.M.; Weiss, J.M.; Kind, A.J.H.; Robbins, J.A. Senescent swallowing: Impact, strategies, and interventions. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2009, 24, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M. Dysphagia and quality of life: A narrative review. Ann. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.P.; Nguyen, L.T.; Hirose, K.; Nguyen, T.H.; Le, H.T.; Shimura, F.; Yamamoto, S. Malnutrition is associated with dysphagia in Vietnamese older adult inpatients. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 30, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajati, F.; Ahmadi, N.; Naghibzadeh, Z.A.S.; Kazeminia, M. The global prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.N.; Ho, W.C.; Wang, L.H.; Chang, F.C.; Nhu, N.T.; Chou, L.W. Prevalence and methods for assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.S.; Kim, H.E.; Choi, J.S. Oral Health-related factors associated with dysphagia risk among older, healthy, community-dwelling Korean adults: A pilot study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, M.; Humbert, I.; Winegrad, H.; Cappola, A.R.; Fried, L.P. Dysphagia in old-old women: Prevalence as determined according to self-report and the 3-ounce water swallowing test. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehring, B.; Hind, J.; Fidler, E.; Krueger, D.; Binkley, N.; Robbins, J. Tongue strength is associated with jumping mechanography performance and handgrip strength but not with classic functional tests in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rjoob, M.; Hassan, N.F.H.N.; Aziz, M.A.A.; Zakaria, M.N.; Mustafar, M.F.B.M. Quality of life in stroke patients with dysphagia: A systematic review. Tunis. Med. 2022, 100, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayres, A.; Jotz, G.P.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Schuh, A.F.S.; Olchik, M.R. The impact of dysphagia therapy on quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease as measured by the swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire (SWALQOL). Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 20, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.C.; Pernambuco, L.A.; Magalhães, H. Quality of life in dysphagia and functional performance of cancer patients in palliative care. CoDAS 2024, 36, e20230266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Park, Y.H. The risk of dysphagia and dysphagia-specific quality of life among community dwelling older adults in senior center. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2014, 26, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Speyer, R.; Kertscher, B.; Denman, D.; Swan, K.; Cordier, R. Health-related quality of life and oropharyngeal dysphagia: A systematic review. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.H.; Golub, J.S.; Hapner, E.R.; Johns, M.M. Prevalence of perceived dysphagia and quality-of-life impairment in a geriatric population. Dysphagia 2009, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, T.; Gillies, R.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Wagner, P.J. The prevalence of dysphagia in primary care patients: A HamesNet Research Network study. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2007, 20, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Carmona, R.; Traube, M. Dysphagia in the elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosiegel, M.; Riecker, A.; Weinert, M.; Dziewas, R.; Lindner-Pfleghar, B.; Stanschus, S.; Warnecke, T. Management of dysphagic patients with acute stroke. Nervenarzt 2012, 83, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kwon, Y. Standardization of Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-K) for use in the elderly. Part II. diagnosis validity. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 1989, 28, 508–513. [Google Scholar]

- Won, C.W.; Rho, Y.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, B.R.; Lee, Y.S. The validity and reliability of Korean activities of daily living (K-ADL) Scale. J. Korean Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 6, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. National Survey of Older Koreans; Ministry of Health and Welfare∙Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2014; pp. 337–342. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10107010100&bid=0040&act=view&list_no=358659&tag=&cg_code=&list_depth=1 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.M.S.V.; Schimmel, M.; van der Bilt, A.; Chen, J.; van der Glas, H.W.; Kohyama, K.; Hennequin, M.; Peyron, M.A.; Woda, A.; Leles, C.R.; et al. Consensus on the terminologies and methodologies for masticatory assessment. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashiro, T.; Wada, S.; Kawate, N. The use of color-changeable chewing gum in evaluating food masticability. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, J.; Kamakura, Y.; Manzai, T.; Kitaike, T. Development of dysphagia risk screening system for elderly persons. Jpn J. Dysphagia Rehabil. 2006, 10, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, S.A. Dysphagia Risks, Activities of Daily Living, and Depression among Community Dwelling Elders. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oguchi, K.; Saitoh, E.; Mizuno, M.; Baba, M.; Okui, M.; Suzuki, M. The Repetitive Saliva Swallowing Test (RSST) as a screening test of functional dysphagia (1) Normal values of RSST. Jpn J. Rehabil. Med. 2000, 37, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M.; Wiggins, R.D.; Higgs, P.; Blane, D.B. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljas, A.E.M.; Jones, A.; Cadar, D.; Steptoe, A.; Lassale, C. Association of multisensory impairment with quality of life and depression in English older adults. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Perez-Rojo, G.; Noriega, C.; Sánchez-Cabaco, A.; Sitges, E.; Bonete, B. Quality-of-life in older adults: Its association with emotional distress and psychological wellbeing. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; McGarrigle, C.A.; Kenny, R.A. More than health: Quality of life trajectories among older adults-findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study of Ageing (TILDA). Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, M.; Higgs, P.; Wiggins, R.D.; Blane, D. A decade of research using the CASP scale: Key findings and future directions. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.J.; Kim, G.E. A validation study of the Korean version of the CASP-16. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2022, 42, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, F.M.A. Gender difference in domain-specific quality of life measured by modified WHOQOL-bref questionnaire and their associated factors among older adults in a rural district in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea; Statistics Research Institute. Statistics Research Institute, Quality of Life Indicators in Korea 2024; Statistics Korea, Statistics Research Institute: Daejeon, Republic of Korea. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=b10105000000&bid=0060&act=view&list_no=437505 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Development and Application of a Quality of Life Indicator System for Older Persons; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, K.; Kikutani, T.; Tamura, F. Survey of suspected dysphagia prevalence in home-dwelling older people using the 10-Item Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodderi, T.; Sreenath, D.; Shetty, M.J.; Chilwan, U.; Rai, S.P.V.; Moolambally, S.R.; Balasubramanium, R.K.; Kothari, M. Prevalence of self-reported swallowing difficulties and swallowing-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in India. Dysphagia 2024, 39, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamoto, Y.; Kaneoka, A. Swallowing disorders in the elderly. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2022, 10, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.S. Orofacial muscle strength and associated potential factors in healthy Korean community-dwelling older adults: A pilot cross-sectional study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mituuti, C.T.; Bianco, V.C.; Bentim, C.G.; de Andrade, E.C.; Rubo, J.H.; Berretin-Felix, G. Influence of oral health condition on swallowing and oral intake level for patients affected by chronic stroke. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleedaeng, P.; Korwanich, N.; Muangpaisan, W.; Korwanich, K. Effect of dysphagia on the older adults’ nutritional status and meal pattern. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231158280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.G.; Jagtap, M. Impact of swallowing impairment on quality of life of individuals with dysphagia. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 74 (Suppl. 3), 5473–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornan, M.; Semple, C.; Moorhead, A.; McCaughan, E. A qualitative systematic review of the social eating and drinking experiences of patients following treatment for head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4899–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.S.; Shiba, K.; Boehm, J.K.; Kubzansky, L.D. Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, S.N.; Juliana, N.; Azmani, S.; Abu, I.F.; Talib, A.H.Q.A.; Abdullah, F.; Salehuddin, I.Z.; Teng, N.I.M.F.; Amin, N.A.; Azmi, N.A.S.M.; et al. Impact of religious activities on quality of life and cognitive function among elderly. J. Relig. Health 2022, 61, 1564–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.O. Effects of physical health status, social support, and depression on quality of life in the Korean community-dwelling elderly. Adv. Public Health 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | General Quality of Life | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t, F, or x2 (p) | ||

| Sex | 0.686 | ||

| Male | 13 | 37.54 ± 12.15 | (0.494) |

| Female | 92 | 35.51 ± 9.65 | |

| Age group (years) | 1.252 | ||

| 60s | 26 | 38.42 ± 9.13 | (0.290) |

| 70s | 58 | 34.98 ± 10.68 | |

| 80s | 21 | 34.62 ± 8.53 | |

| Education | 2.021 | ||

| ≤Elementary | 31 | 33.19 ± 8.84 | (0.116) |

| Middle school diploma | 29 | 37.17 ± 10.33 | |

| High school diploma | 26 | 34.46 ± 10.53 | |

| ≥Junior college | 19 | 39.58 ± 9.43 | |

| Economic status | x2 = 9.418 | ||

| High | 40 | 39.50 ± 8.44 a | (0.009) |

| Middle | 62 | 33.23 ± 10.32 b | |

| Low | 3 | 38.33 ± 3.78 ab | |

| Religion | 2.443 | ||

| None | 31 | 33.71 ± 11.01 | (0.069) |

| Buddhist | 26 | 33.15 ± 11.08 | |

| Christian | 34 | 39.00 ± 7.27 | |

| Catholic | 14 | 37.29 ± 9.38 | |

| Total | 105 | 35.76 ± 9.94 | |

| Variables | n | General Quality of Life | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t, F, or x2 (p) | ||

| Health check-up in past 2 years | 1.398 | ||

| Yes | 93 | 36.25 ± 10.01 | (0.165) |

| No | 12 | 32.00 ± 8.94 | |

| Smoking status | x2 = 0.095 | ||

| Current smoker | 3 | 35.00 ± 9.84 | (0.954) |

| Former smoker | 9 | 34.11 ± 12.86 | |

| Never smoker | 93 | 35.95 ± 9.75 | |

| Alcohol consumption (current) | −1.611 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 40.08 ± 9.72 | (0.110) |

| No | 93 | 35.20 ± 9.89 | |

| High-intensity exercise (≥10 min per day) | 0.674 | ||

| Yes | 23 | 37.00 ± 10.94 | (0.502) |

| No | 82 | 35.41 ± 9.69 | |

| Moderate-intensity exercise (≥10 min per day) | 2.205 | ||

| Yes | 54 | 37.80 ± 10.48 | (0.030) |

| No | 51 | 33.61 ± 8.94 | |

| Frequency of daily toothbrushing | −2.731 | ||

| 0–2 times | 46 | 32.85 ± 11.08 | (0.007) |

| ≥3 times | 59 | 38.03 ± 8.37 | |

| Periodic dental check-ups | 2.090 | ||

| Yes | 73 | 37.04 ± 10.05 | (0.041) |

| No | 32 | 32.84 ± 9.20 | |

| Periodic dental scaling | 2.826 | ||

| Yes | 73 | 37.52 ± 9.63 | (0.006) |

| No | 32 | 31.75 ± 9.63 | |

| Tongue cleaning | x2 = 1.957 | ||

| Always (every day) | 68 | 36.59 ± 10.14 | (0.376) |

| Sometimes (every 1 or 2 weeks) | 30 | 33.94 ± 9.90 | |

| Never | 7 | 35.43 ± 8.26 | |

| Use of interdental cleaning devices | 0.310 | ||

| Always (every day) | 37 | 36.19 ± 10.88 | (0.734) |

| Sometimes (every 1 or 2 weeks) | 39 | 39.28 ± 8.56 | |

| Never | 29 | 34.52 ± 10.65 | |

| Variables | n | General Quality of Life | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t, F, or x2 (p) | ||

| Self-perceived general health status | x2 = 10.166 | ||

| Poor | 9 | 33.67 ± 7.43 ab | (0.006) |

| Fair | 54 | 33.11 ± 10.77 a | |

| Good | 42 | 39.62 ± 8.05 b | |

| Number of systemic diseases | 2.228 | ||

| 0–1 | 33 | 38.91 ± 9.83 | (0.030) |

| ≥2 | 72 | 34.32 ± 9.73 | |

| Self-perceived stress status | x2 = 13.865 | ||

| Very low | 37 | 39.84 ± 8.92 a | (0.003) |

| Low | 46 | 33.87 ± 10.23 a | |

| High | 19 | 34.74 ± 8.20 a | |

| Very high | 3 | 21.00 ± 5.00 b | |

| Frailty status | x2 = 6.416 | ||

| Robust | 59 | 36.90 ± 9.70 a | (0.040) |

| Pre-frailty | 41 | 35.32 ± 10.24 ab | |

| Frailty | 5 | 26.00 ± 4.24 b | |

| History of toothache | −0.971 | ||

| Yes | 35 | 34.43 ± 10.60 | (0.334) |

| No | 70 | 36.43 ± 9.61 | |

| Masticatory discomfort | 0.742 | ||

| Yes | 19 | 33.79 ± 10.90 | (0.479) |

| Slight | 18 | 34.61 ± 11.24 | |

| No | 68 | 36.62 ± 9.35 | |

| Number of remaining teeth | −2.732 | ||

| 0–25 | 29 | 31.52 ± 9.95 | (0.009) |

| ≥26 | 76 | 37.38 ± 9.52 | |

| Use of dentures | 1.352 | ||

| No | 91 | 36.27 ± 9.99 | (0.179) |

| Yes | 14 | 32.43 ± 9.29 | |

| Need for dental prostheses (maxillary) | 2.247 | ||

| No | 61 | 37.57 ± 9.84 | (0.027) |

| Yes | 44 | 33.25 ± 9.64 | |

| Need for dental prostheses (mandibular) | 1.772 | ||

| No | 64 | 37.13 ± 9.78 | (0.079) |

| Yes | 41 | 33.63 ± 9.94 | |

| Chewing ability (score) | 4.543 | ||

| 6–7 | 15 | 31.93 ± 11.46 a | (0.013) |

| 8 | 63 | 34.73 ± 9.73 ab | |

| 9–10 | 27 | 40.30 ± 8.17 b | |

| Dysphagia risk (DRAS) | 2.483 | ||

| Normal (score ≤ 5) | 73 | 37.38 ± 9.35 | (0.016) |

| High risk (score ≥ 6) | 32 | 32.06 ± 10.42 | |

| Dysphagia risk (RSST) | 2.494 | ||

| Normal (≥3 times) | 27 | 39.78 ± 9.09 | (0.014) |

| High risk (≤2 times) | 78 | 34.37 ± 9.90 | |

| Division | Variables | β | t | p-Value * | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic status | 0.240 | 2.727 | 0.008 | 1.185 | |

| Religion = Christian (ref. Non-Christian) | 0.226 | 2.715 | 0.008 | 1.062 | |

| Moderate-intensity exercise (No) (ref. Yes) | −0.190 | −2.323 | 0.022 | 1.030 | |

| Model 1 | Frequency of daily toothbrushing | 0.223 | 2.659 | 0.009 | 1.074 |

| Periodic scaling (No) (ref. Yes) | −0.187 | −2.233 | 0.028 | 1.073 | |

| Self-perceived stress levels | −0.206 | −2.397 | 0.018 | 1.134 | |

| High-risk group for swallowing dysfunction (DRAS score ≥6) | −0.179 | −2.171 | 0.032 | 1.038 | |

| F = 8.048 (<0.001), adj. R2 = 0.322, Durbin-Watson = 1.911 | |||||

| Economic status | 0.237 | 2.698 | 0.008 | 1.188 | |

| Religion = Christian (ref. Non-Christian) | 0.256 | 3.055 | 0.003 | 1.081 | |

| Moderate-intensity exercise (No) (ref. Yes) | −0.218 | −2.613 | 0.010 | 1.071 | |

| Model 2 | Frequency of daily toothbrushing | 0.190 | 2.228 | 0.028 | 1.126 |

| Periodic scaling (No) (ref. Yes) | −0.185 | −2.219 | 0.029 | 1.073 | |

| Self-perceived stress levels | −0.199 | −2.311 | 0.023 | 1.142 | |

| High-risk group for swallowing dysfunction (RSST times ≤ 2) | −0.201 | −2.331 | 0.022 | 1.147 | |

| F = 8.203 (<0.001), adjusted R2 = 0.327, Durbin-Watson = 1.891 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.-A.; Choi, J.-S. Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction and Multidimensional Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Healthy Korean Older Adults: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2964. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222964

Jang H-A, Choi J-S. Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction and Multidimensional Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Healthy Korean Older Adults: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2964. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222964

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Hyun-Ah, and Jun-Seon Choi. 2025. "Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction and Multidimensional Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Healthy Korean Older Adults: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2964. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222964

APA StyleJang, H.-A., & Choi, J.-S. (2025). Association Between Swallowing Dysfunction and Multidimensional Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Healthy Korean Older Adults: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(22), 2964. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222964