Assessing the Consultation Pattern from Emergency Room Physicians to General Surgery Subspecialties: Identifying the Most Frequently Consulted Subspecialty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients

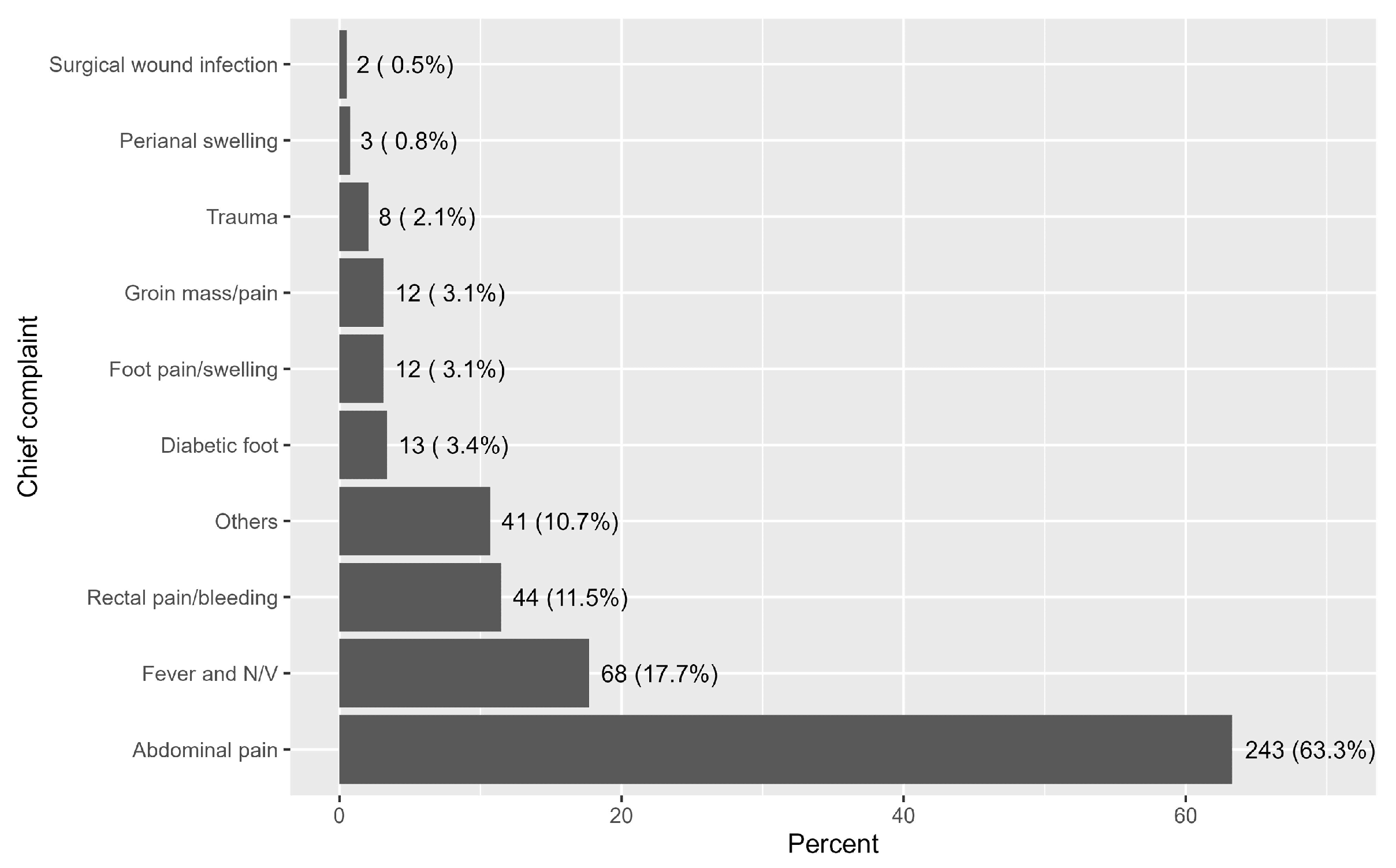

Description of Chief Complaints and Surgical Procedures

3.2. Description of Surgeries Performed to Patients

3.3. Characteristics of Subspecialties and Referral Sites

3.4. Statistical Differences Based on Subspecialties

3.5. Statistical Differences Based on Referral Sites

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute Care Surgery |

| AAST | American Association for the Surgery of Trauma |

| EGS | Emergency General Surgery |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GS | General Surgery |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| KAMC | King Abdulaziz Medical City |

| MNGHA | Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs |

| RR | Relative Risk |

| RStudio | R Statistical Computing Software |

References

- Smith, G.W. What is general surgery? Who is a general surgeon? Arch. Surg. 1981, 116, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons. Statements on Principles and Standards in General Surgery. Available online: https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/statements-on-principles/ (accessed on 12 April 2016).

- Beckerleg, W.; Wooller, K.; Hasimjia, D. Interventions to reduce emergency department consultation time: A systematic review of the literature. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 22, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimalananda, V.G.; Gupte, G.; Seraj, S.M.; Orlander, J.; Berlowitz, D.; Fincke, B.G.; Simon, S.R. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J.J.; Sutherland, J.; Symington, C.; Dorland, K.; Mansour, M.; Stiell, I.G. Assessment of the impact on time to complete medical record using an electronic medical record versus a paper record on emergency department patients. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faryniuk, A.M.; Hochman, D.J. Effect of an acute care surgical service on the timeliness of care. Can. J. Surg. 2013, 56, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, S.C.; Shafi, S.; Dombrovskiy, V.Y.; Arumugam, D.; Crystal, J.S. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: A 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample--2001 to 2010. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celepli, S.; Türkoğlu, B.; Ulusoy, S.; Tuncal, S.; Akkapulu, N.; Eryılmaz, M. The effect of emergency room consultations on emergency general surgery operations. Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 28, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruenderman, E.H.; Block, S.B.; Kehdy, F.J.; Benns, M.V.; Miller, K.R.; Motameni, A.; Nash, N.A.; Bozeman, M.C.; Martin, R.C. An evaluation of emergency general surgery transfers and a call for standardization of practices. Surgery 2021, 169, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, R.D.; Sukumar, N.; DeWane, M.P.; Gill, T.M.; Maung, A.A.; Schuster, K.M.; Stolar, M.J.; Davis, K.A.M. Regionalization of emergency general surgery operations: A simulation study. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 88, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wee, M.J.; van der Wilden, G.; Hoencamp, R. Acute care surgery models worldwide: A systematic review. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 2622–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahramanca, S.; Kaya, O.; Azili, C.; Guzel, H.; Ozgehan, G.; Irem, B. The role of general surgery consultations in patient management. Turk. J. Surg. /Ulus. Cerrahi Derg. 2013, 29, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, K.B.; Kamdar, N.S.; Patil, P.; Collins, S.D.; Seese, E.; Krapohl, G.L.; Campbell, D.; Englesbe, M.J.; Hemmila, M.R.; Napolitano, L.M. Acute Care Surgery Model and Outcomes in Emergency General Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Lim, W.W.; Goo, T.T. Emergency general surgery and trauma: Outcomes from the first consultant-led service in Singapore. Injury 2018, 49, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abood, H.B.A.; Alotibi, M.M.; Alhashim, Z.A.; Alotaibi, E.H.; Alkandari, S.A.; Yousif, R.M.A.; Almahdi, S.A.; Alshaqaqiq, R.A.; Alruwaili, W.S.; Almohaissen, E.A. Emergency surgical interventions: A comparative review of acute cases in general surgery and orthopedic surgery. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2025, 9, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleid, A.M.; Alyabis, N.A.; Alghamidi, F.A.; Almuneef, R.H.; Alquraini, S.K.; Alsuraykh, L.A.; Al Amer, A.M.; AlQifari, H.S.; Alsharari, W.A.; Albishri, N.F.; et al. Retrospective analysis of general surgery outcomes in multicenter cohorts in Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Life 2025, 18, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanis, K.N.; Hunter, A.M.; Harington, M.B.; Groot, G. Impact of an acute care surgery service on timeliness of care and surgeon satisfaction at a Canadian academic hospital: A retrospective study. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2014, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yin, Y.; Hou, L.; Zhou, H. A special acute care surgery model for dealing with dilemmas involved in emergency department in China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiner, S.; Kurtoğlu, I.; Durmuş, M.; Şahin, K.C.; Altiner, Ö.T.; Dikmen, A.U.; Büyükkasap, Ç.; YAVUZ, A.; Pekcici, M.R.; Barlas, A.M. The role of general surgery consultations on patient diagnosis and treatment in the tertiary medical center. Arch. Curr. Med. Res. 2024, 5, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, A.D.; McCullough, M.A.; Stettler, G.R. Time-sensitive emergency general surgery: Saving lives and reducing cost. Curr. Surg. Rep. 2025, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, D.A.; Imtiaz, M.L. An analysis of referrals from primary care. Saudi Med. J. 2004, 25, 671–673. [Google Scholar]

- Alaqil, N.A.N.; Alanazi, B.G.; Alghamdi, S.A.A.; Alanazi, M.G.; Alghamdi, A.A.A.; Almalki, A.M.O.; Alamri, F.B.H. The role of urgent care clinics in alleviating emergency department congestion: A systematic review of patient outcomes and resource utilization. Cureus 2025, 17, e81919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | - |

| <30 | 98 (25.5%) |

| 30 to <45 | 112 (29.2%) |

| 45 to <60 | 86 (22.4%) |

| 60 or more | 88 (22.9%) |

| Gender | - |

| Male | 204 (53.1%) |

| Female | 180 (46.9%) |

| Comorbidities | - |

| Diabetes | 94 (24.5%) |

| Hypertension | 90 (23.4%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 37 (9.6%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (0.3%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 (4.2%) |

| Liver Disease | 6 (1.6%) |

| Malignancy | 23 (6.0%) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 5 (1.3%) |

| n (%) | |

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Surgical intervention | - |

| Amputation | 11 (2.9%) |

| Anorectal examination | 45 (11.7%) |

| Colonic procedure | 16 (4.2%) |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy | 22 (5.7%) |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 20 (5.2%) |

| Gastrectomy | 3 (0.8%) |

| Hernia repair | 27 (7.0%) |

| Incision and drainage | 9 (2.3%) |

| Laparoscopic appendicectomy | 57 (14.8%) |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 123 (32.0%) |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy proceeding to open cholecystectomy | 5 (1.3%) |

| Pilonidal sinus | 7 (1.8%) |

| Soft tissue excision | 17 (4.4%) |

| Others | 11 (2.9%) |

| Length of stay (days) | 3.0 (2.0–8.0) |

| n (%); Median (IQR) The variable had 107 missing records | |

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Subspecialty | - |

| Colorectal | 86 (23.0%) |

| Acute care | 231 (61.8%) |

| Upper GI | 40 (10.7%) |

| Oncology | 12 (3.2%) |

| Endocrine | 3 (0.8%) |

| Vascular | 2 (0.5%) |

| Referral site | - |

| Acute care (From ER to general surgery) | 355 (98.9%) |

| Characteristic | Colorectal N = 86 | Acute Care N = 231 | Upper GI N = 40 | Oncology N = 12 | Endocrine N = 3 | Vascular N = 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.069 |

| <30 | 11 (12.8%) | 70 (30.3%) | 11 (27.5%) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 30 to <45 | 30 (34.9%) | 62 (26.8%) | 12 (30.0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 45 to <60 | 23 (26.7%) | 48 (20.8%) | 8 (20.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 60 or more | 22 (25.6%) | 51 (22.1%) | 9 (22.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | - |

| Gender | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.049 |

| Male | 56 (65.1%) | 119 (51.5%) | 15 (37.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | - |

| Female | 30 (34.9%) | 112 (48.5%) | 25 (62.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (50.0%) | - |

| Comorbidities | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DM | 23 (26.7%) | 54 (23.4%) | 9 (22.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0.830 |

| HTN | 23 (26.7%) | 53 (22.9%) | 7 (17.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0.467 |

| CVD | 9 (10.5%) | 22 (9.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.401 |

| COPD | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| CKD | 4 (4.7%) | 7 (3.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0.175 |

| Liver Disease | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (7.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.049 |

| Malignancy | 12 (14.0%) | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.008 |

| IBD | 3 (3.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.143 |

| Abdominal pain | 30 (36.6%) | 167 (74.9%) | 31 (79.5%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Fever and N/V | 5 (6.1%) | 50 (22.4%) | 6 (15.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Others | 10 (12.2%) | 16 (7.2%) | 7 (17.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Rectal pain/bleeding | 39 (47.6%) | 4 (1.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetic foot | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (5.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.119 |

| Foot pain/swelling | 3 (3.7%) | 7 (3.1%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0.131 |

| Groin mass/pain | 1 (1.2%) | 10 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.500 |

| Perianal swelling | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.359 |

| Surgical wound infection | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.610 |

| Trauma | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.405 |

| n (%) | |||||||

| Fisher’s exact test | |||||||

| Characteristic | Acute Care N = 355 | General Surgery Outpatient Clinic N = 4 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | - | - | 0.083 |

| <30 | 96 (27.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 30 to <45 | 104 (29.3%) | 1 (25.0%) | - |

| 45 to <60 | 78 (22.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 60 or more | 77 (21.7%) | 3 (75.0%) | - |

| Gender | - | - | >0.999 |

| Male | 189 (53.2%) | 2 (50.0%) | - |

| Female | 166 (46.8%) | 2 (50.0%) | - |

| Comorbidities | - | - | - |

| DM | 83 (23.4%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.239 |

| HTN | 78 (22.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.216 |

| CVD | 34 (9.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| COPD | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| CKD | 15 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Liver Disease | 6 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Malignancy | 21 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| IBD | 5 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Chief complaint | - | - | - |

| Abdominal pain | 225 (66.4%) | 3 (75.0%) | >0.999 |

| Fever and N/V | 61 (18.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.022 |

| Others | 40 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Rectal pain/bleeding | 41 (12.1%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.408 |

| Diabetic foot | 13 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Foot pain/swelling | 8 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Groin mass/pain | 10 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Perianal swelling | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Surgical wound infection | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| Trauma | 8 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.999 |

| n (%) | |||

| Fisher’s exact test | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Babtain, I.T.; Alwabel, W.K.; Alhoumaily, B.A.; Alqahtani, N.A.; Almasari, R.M.; Tatwani, H.T. Assessing the Consultation Pattern from Emergency Room Physicians to General Surgery Subspecialties: Identifying the Most Frequently Consulted Subspecialty. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2955. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222955

Al Babtain IT, Alwabel WK, Alhoumaily BA, Alqahtani NA, Almasari RM, Tatwani HT. Assessing the Consultation Pattern from Emergency Room Physicians to General Surgery Subspecialties: Identifying the Most Frequently Consulted Subspecialty. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2955. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222955

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Babtain, Ibrahim Tawfiq, Wed Khalid Alwabel, Bader Abdulhadi Alhoumaily, Nawaf Abdullah Alqahtani, Renad Mousa Almasari, and Hashim Tariq Tatwani. 2025. "Assessing the Consultation Pattern from Emergency Room Physicians to General Surgery Subspecialties: Identifying the Most Frequently Consulted Subspecialty" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2955. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222955

APA StyleAl Babtain, I. T., Alwabel, W. K., Alhoumaily, B. A., Alqahtani, N. A., Almasari, R. M., & Tatwani, H. T. (2025). Assessing the Consultation Pattern from Emergency Room Physicians to General Surgery Subspecialties: Identifying the Most Frequently Consulted Subspecialty. Healthcare, 13(22), 2955. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222955