Digital Health in Early Childhood: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Practices, and Training Needs in Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Demographic and professional information (e.g., number of patients managed, district of practice),

- Basic knowledge of digital education and the use of digital devices in early childhood,

- Familiarity with national guidelines, specifically those issued by the SIP,

- The degree to which these guidelines are incorporated into routine clinical practice, and

- PCPs’ perceived need for additional training in this area.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Ethical Considerations, Patient Information, and Written Informed Consent

3. Results

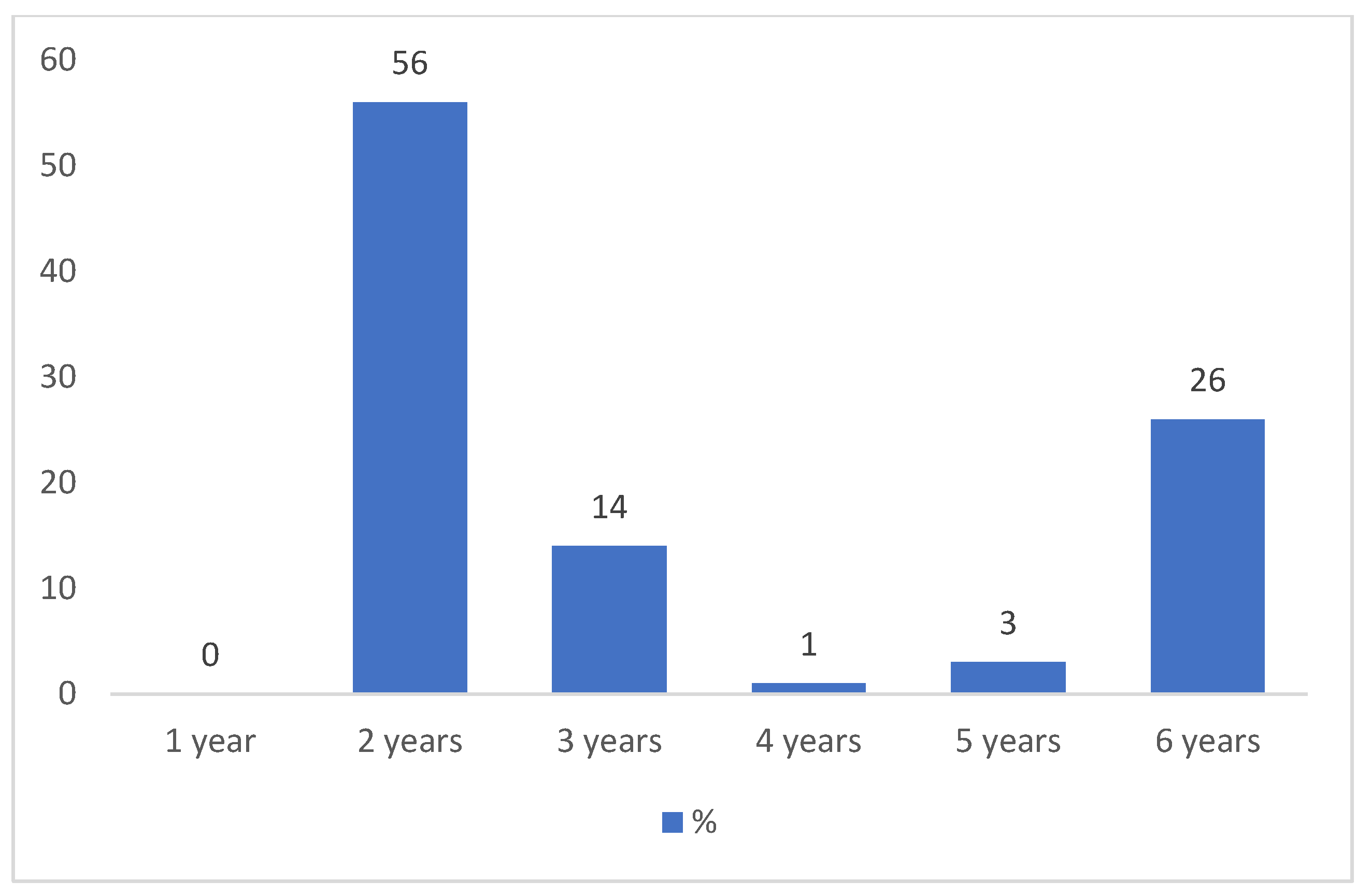

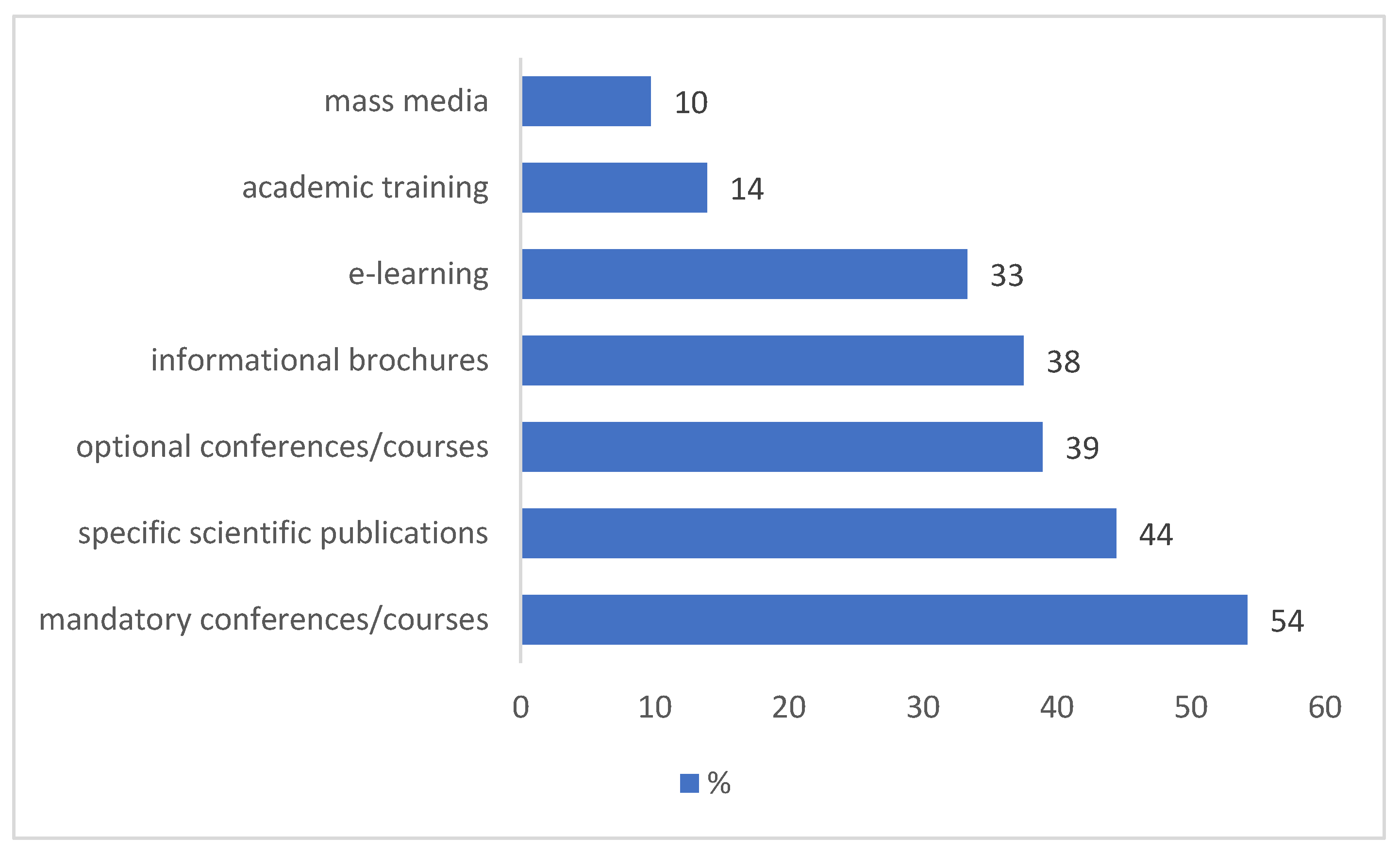

3.1. Knowledge About the Recommendations on the Correct Use of DDs Stated by the Italian Pediatric Society (SIP)

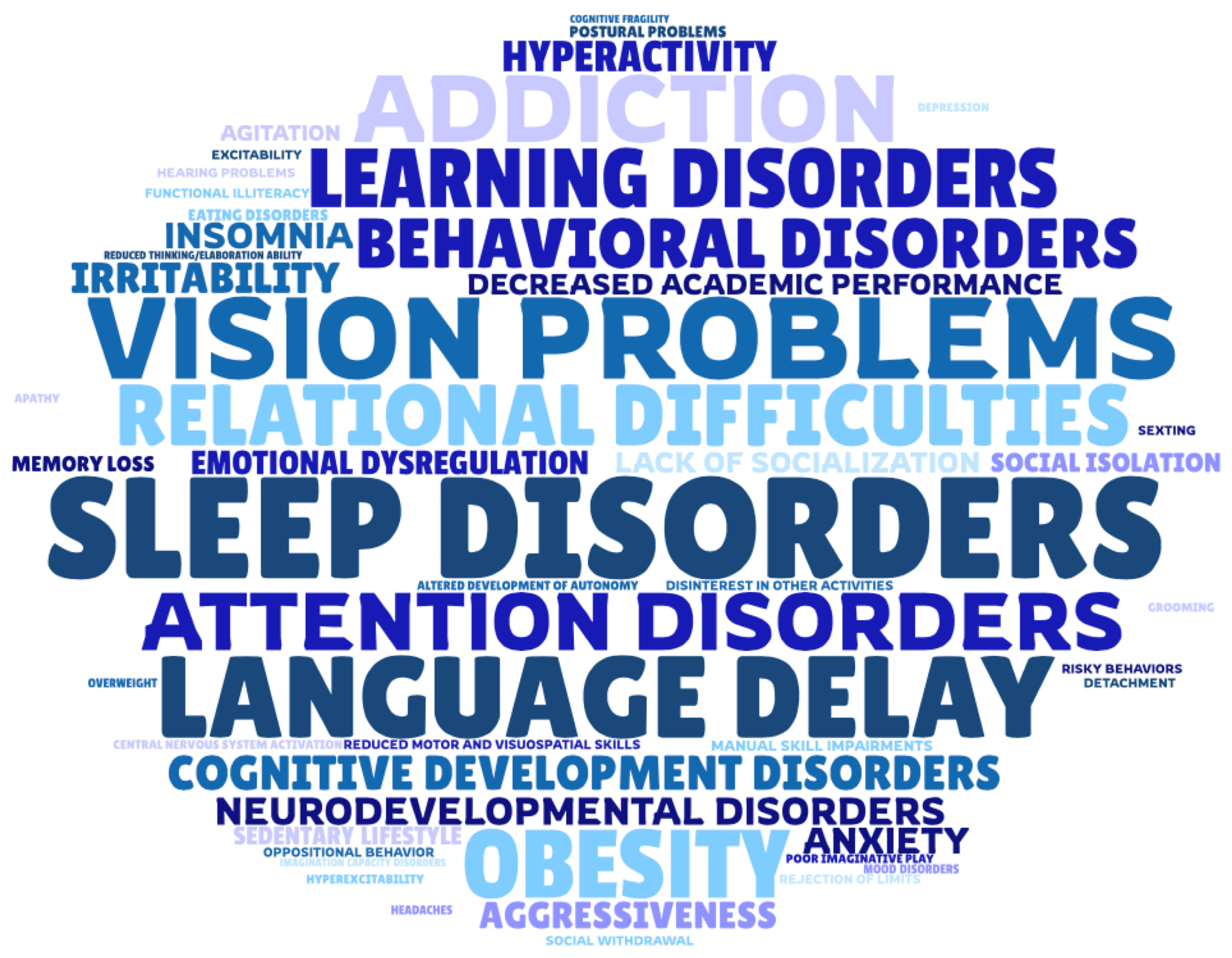

3.2. Knowledge of the Adverse Effects of Excessive DDs Use

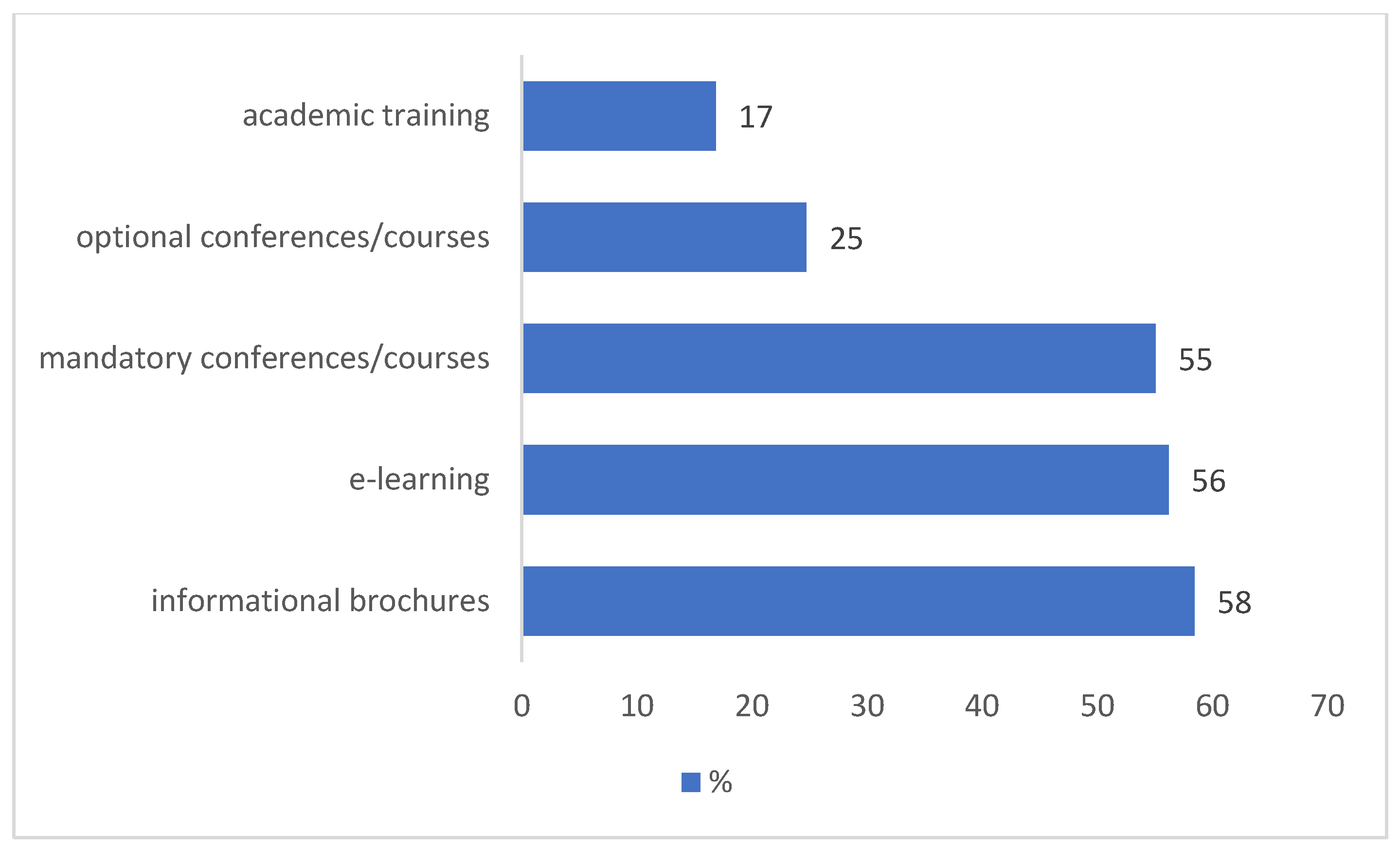

3.3. PCPs’ Practice in Terms of Digital Education and Their Knowledge Demands

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DD | Digital devices |

| DE | Digital Education |

| PCPs | Primary Care Pediatricians |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SIP | Italian Pediatric Society |

Appendix A

- Quanti sono i suoi assistiti in totale? (specificare il numero)→ _____

- Quanti sono i suoi assistiti sotto i 6 anni? (specificare il numero)?→ _____

- In che provincia lavora?

- ⃞

- Modena

- ⃞

- Reggio Emilia

- Il distretto in cui lavora, si può definire:

- ⃞

- Zona urbana o zona industrializzata

- ⃞

- Zona rurale

- Conosce le raccomandazioni SIP sull’utilizzo dei Dispositivi Digitali? *

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- Se SI, tramite quali canali ha avuto informazioni su tale argomento: (possibili più scelte) Seleziona tutte le voci applicabili.

- ⃞

- Formazione accademica

- ⃞

- Congressi/Corsi obbligatori

- ⃞

- Congressi/Corsi facoltativi FAD

- ⃞

- Opuscoli informativi

- ⃞

- Pubblicazioni scientifiche specifiche

- ⃞

- Mass media

- Sa fino a che età (anni) sarebbe opportuno evitare completamente l’utilizzo dei Dispositivi Digitali?

- ⃞

- 1

- ⃞

- 2

- ⃞

- 3

- ⃞

- 4

- ⃞

- 5

- ⃞

- 6

- Conosce i limiti di esposizione ai Dispositivi Digitali a seconda delle fasce di età?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- In quale delle seguenti occasioni sarebbe opportuno evitare l’utilizzo dei Dispositivi Digitali? (possibili più scelte). Seleziona tutte le voci applicabili.

- ⃞

- Durante i pasti

- ⃞

- Almeno 1 ora prima di andare a letto

- ⃞

- In caso di programmi a ritmo sostenuto, applicazioni con contenuti distraenti o violenti

- ⃞

- Per tenere i bambini tranquilli in luoghi pubblici

- ⃞

- Durante le visite mediche

- Conosce gli effetti a lungo termine dell’esposizione ai Dispositivi Digitali in età prescolare?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- Se SI, può elencarli? (almeno 3)→ _______________________________________

- Durante i bilanci di salute affronta tale argomento con i genitori dei suoi assistiti?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- Se SI, fornisce consigli pratici ai genitori, tentando quindi di limitare l’esposizione a Dispositivi Digitali dei suoi assistiti?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- Quanto ritiene importante informare i genitori dei suoi assistiti sugli effetti dei Dispositivi Digitali?

- ⃞

- Non importante

- ⃞

- Importante ma non fondamentale

- ⃞

- Molto importante

- Vorrebbe più informazioni sull’argomento?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- Se SI, quale tipo di formazione preferirebbe? (possibili più scelte). Seleziona tutte le voci applicabili.

- ⃞

- Formazione accademica

- ⃞

- Congressi/Corsi obbligatori

- ⃞

- Congressi/Corsi facoltativi

- ⃞

- FAD

- ⃞

- Opuscoli informativi

- Ritiene utile la diffusione di brevi brochures su tale argomento nella sua pratica clinica (e.g., opuscoli specifici da lasciare in sala d’attesa)?

- ⃞

- Si

- ⃞

- No

- ⃞

- Non so

- What is your total patient load? (Please specify the number)→ _____

- How many children under the age of 6 are currently in your care? (Please specify the number)→ _____

- In which province do you practice?

- ⃞

- Modena

- ⃞

- Reggio Emilia

- How would you classify the area in which you practice?

- ⃞

- Urban or industrialised area

- ⃞

- Rural area

- Are you familiar with the SIP (Italian Pediatric Society) recommendations on the use of digital devices in early childhood?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- If yes, through which channels did you receive this information? (Multiple answers allowed)

- ⃞

- Academic training

- ⃞

- Mandatory congresses/courses

- ⃞

- Optional congresses/FAD (distance learning)

- ⃞

- Informational brochures

- ⃞

- Scientific publications

- ⃞

- Mass media

- According to your knowledge, up to what age (years) should the use of digital devices be completely avoided?

- ⃞

- 1

- ⃞

- 2

- ⃞

- 3

- ⃞

- 4

- ⃞

- 5

- ⃞

- 6

- Are you aware of the recommended screen time limits for different age groups?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- In which of the following situations should digital device use be avoided? (Multiple answers allowed)

- ⃞

- During meals

- ⃞

- At least one hour before bedtime

- ⃞

- During exposure to fast-paced, distracting, or violent content

- ⃞

- To calm or distract children in public places

- ⃞

- During medical consultations

- Are you aware of the potential long-term effects of digital device use in preschool-aged children?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- If yes, please list at least three of these long-term effects:→ _______________________________________

- Do you address the topic of digital device use with parents during routine health visits?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- If yes, do you provide practical advice to help parents limit their children’s screen time?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- How important do you think it is to inform parents about the effects of digital device use in early childhood?

- ⃞

- Not important

- ⃞

- Important but not essential

- ⃞

- Very important

- Would you like to receive more information or training on this topic?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- If yes, what type of training would you prefer? (Multiple answers allowed)

- ⃞

- Academic training

- ⃞

- Mandatory congresses/courses

- ⃞

- Optional congresses/courses

- ⃞

- FAD (distance learning)

- ⃞

- Informational brochures

- Do you think it would be useful to distribute short brochures on this topic in your clinical practice (e.g., brochures available in the waiting room)?

- ⃞

- Yes

- ⃞

- No

- ⃞

- Not

References

- Pizzi, E.; Salvatore, M.A.; Tomasella, M.; Andreozzi, S.; Donati, S. The Surveillance System on Children Aged 0–2: Results of the 2022 Data Collection; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/sorveglianza02anni/pdf/SORVEGLIANZA%20BAMBINI%200-2%20ANNI.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Mikić, A.; Bergmann, S.; Perejoan Martí, G.; Klein, A.M. “Just a second, mommy’s here”: The impact of mothers’ smartphone use on children’s affect regulation and the quality of mother-child interactions. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1596219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komanchuk, J.; Toews, A.J.; Marshall, S.; Mackay, L.J.; Hayden, K.A.; Cameron, J.L.; Duffett-Leger, L.; Letourneau, N. Impacts of Parental Technoference on Parent-Child Relationships and Child Health and Developmental Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2023, 26, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.L.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Council on Communications and Media. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.K.; Kanai, R. How Has the Internet Reshaped Human Cognition? Neuroscientist 2016, 22, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Piotrowski, J.T. Plugged in: How Media Attract and Affect Youth; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Herrero-Roldán, S.; Rodriguez-Besteiro, S.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Digital Device Usage and Childhood Cognitive Development: Exploring Effects on Cognitive Abilities. Children 2024, 11, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, F.; Marwaha, R. Developmental Stages of Social Emotional Development in Children. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, S.; Browne, D.; Racine, N.; Mori, C.; Tough, S. Association Between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guellai, B.; Somogyi, E.; Esseily, R.; Chopin, A. Effects of screen exposure on young children’s cognitive development: A review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraksa, N.; Veraksa, A.; Gavrilova, M.; Bukhalenkova, D.; Oshchepkova, E.; Chursina, A. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Passive and Active Screen Time on Young Children’s Phonological Memory. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 600687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Dong, X.; Liu, D.; Li, H. How Early Digital Experience Shapes Young Brains During 0–12 Years: A Scoping Review. Early Educ. Dev. 2023, 35, 1395–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, E.; Silva, V.; Caetano, M.; Ribeiro, M.V.V.; Fidalgo, T.M.; Rosa Neto, F.; Sanchez, Z.M.; Surkan, P.J.; Martins, S.S.; Caetano, S.C. Excessive Screen Media Use in Preschoolers Is Associated with Poor Motor Skills. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Ruggiero, M.; Memo, L.; Agostiniani, R.; Bozzola, M.; Corsello, G.; Villani, A. Media devices in pre-school children: The recommendations of the Italian pediatric society. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, 59, L119/1–L119/88. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Determinazione 20 marzo 2008. Linee guida per la classificazione e conduzione degli studi osservazionali sui farmaci. In Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana; Ministero della Giustizia: Rome, Italy, 2008; Volume 149, pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Italy. Decreto Legislativo 10 Agosto 2018, n. 101. Disposizioni per l’adeguamento Della Normativa Nazionale Alle Disposizioni Del Regolamento (UE) 2016/679 Del Parlamento Europeo e Del Consiglio, Del 27 Aprile 2016, Relativo Alla Protezione Delle Persone Fisiche Con Riguardo al Trattamento Dei Dati Personali, Nonché Alla Libera Circolazione Di Tali Dati e Che Abroga La Direttiva 95/46/CE (Regolamento Generale Sulla Protezione Dei Dati). In Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana; Serie Generale; Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 2018; Volume 159, pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.S.; Xu, W.Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.J. Digital competency among pediatric healthcare workers and students: A questionnaire survey. World J. Pediatr. 2025, 21, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, K.A.; Ogilvie, J.D.; Ponti, M.; Miller, M.R.; Yang, F.; Ens, A.R. Paediatricians’ awareness of Canadian screen time guidelines, perception of screen time use, and counselling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Paediatr. Child Health 2023, 28, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gath, M.; Swit, C. Digital media in early childhood: Risk factors for online harm and psychosocial correlates. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 2, 1390276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerosa, T.; Gui, M.; Grollo, M.; di Leva, A.; Oretti, C. Pediatricians’ Recommendations on Screen Media Use Significantly Improve Parents’ Management Behaviors and Self-Efficacy: Evidence from a Quasi-Experimental Study. Health Commun. 2025, 1–13, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trevisani, V.; Zinani, I.; Cattani, S.; Ferrari, E.; Iughetti, L.; Lucaccioni, L. Digital Health in Early Childhood: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Practices, and Training Needs in Northern Italy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222945

Trevisani V, Zinani I, Cattani S, Ferrari E, Iughetti L, Lucaccioni L. Digital Health in Early Childhood: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Practices, and Training Needs in Northern Italy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222945

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrevisani, Viola, Isotta Zinani, Silvia Cattani, Elena Ferrari, Lorenzo Iughetti, and Laura Lucaccioni. 2025. "Digital Health in Early Childhood: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Practices, and Training Needs in Northern Italy" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222945

APA StyleTrevisani, V., Zinani, I., Cattani, S., Ferrari, E., Iughetti, L., & Lucaccioni, L. (2025). Digital Health in Early Childhood: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Practices, and Training Needs in Northern Italy. Healthcare, 13(22), 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222945