Intraoperative Platelet-Rich Plasma Application Improves Scar Healing After Cesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Patient Selection

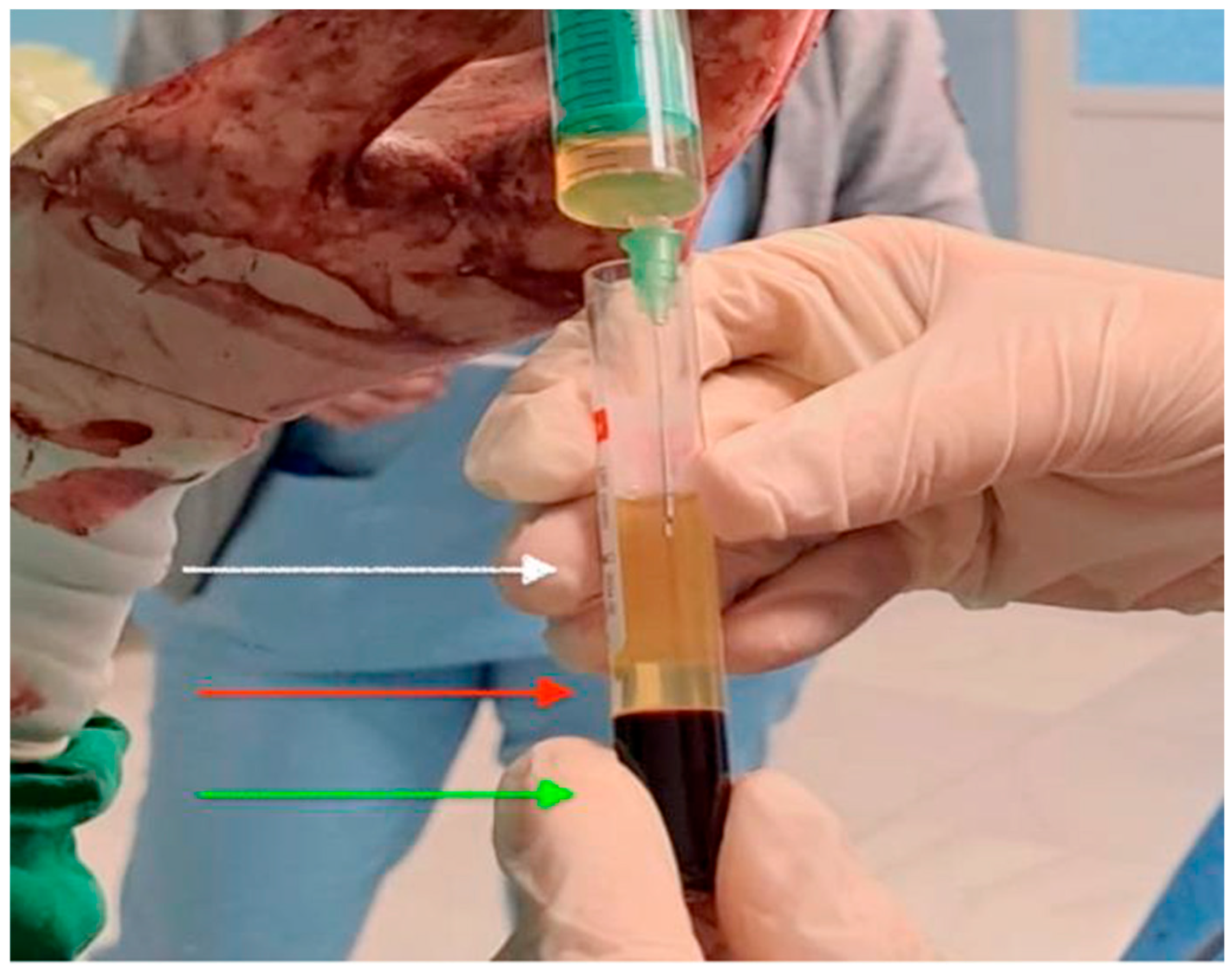

2.3. PRP Preparation and Administration

2.4. Hematological Parameters

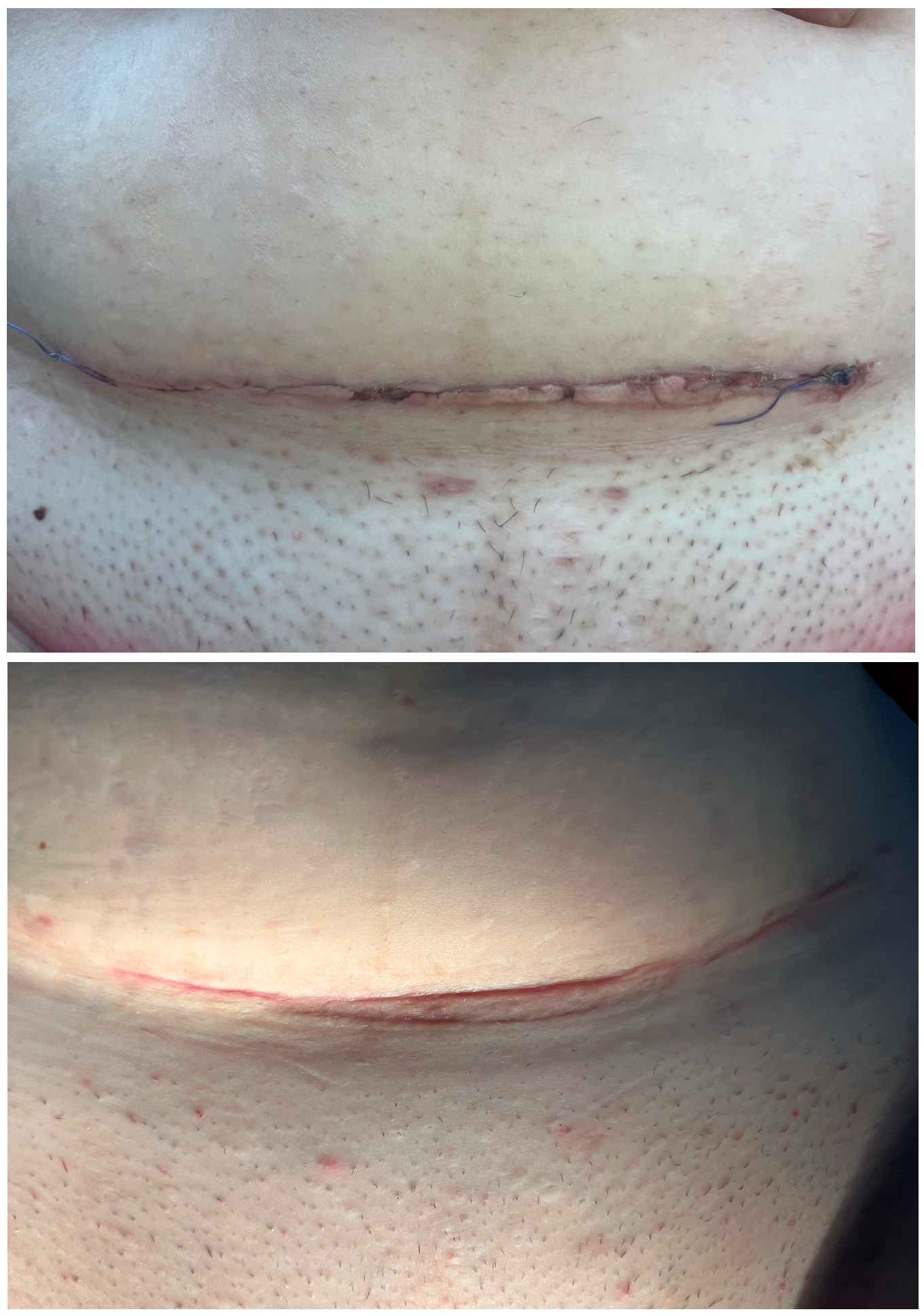

2.5. Scar Assessment Scales

- Manchester Scar Scale (MSS)—clinical assessment of scar thickness, texture, and pigmentation [22].

- Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS)—incorporates both observer and patient perspectives [23].

- Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS)—evaluates vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height [24].

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS)—patient-rated pain intensity (0–10) [25].

- Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)—numerical pain rating (0–10) [26].

- REEDA Scale (Redness, Edema, Ecchymosis, Discharge, Approximation)—evaluates erythema, edema, ecchymosis, discharge, and approximation (0–15 scale) [27].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Timing Rationale

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Scar Healing Outcomes

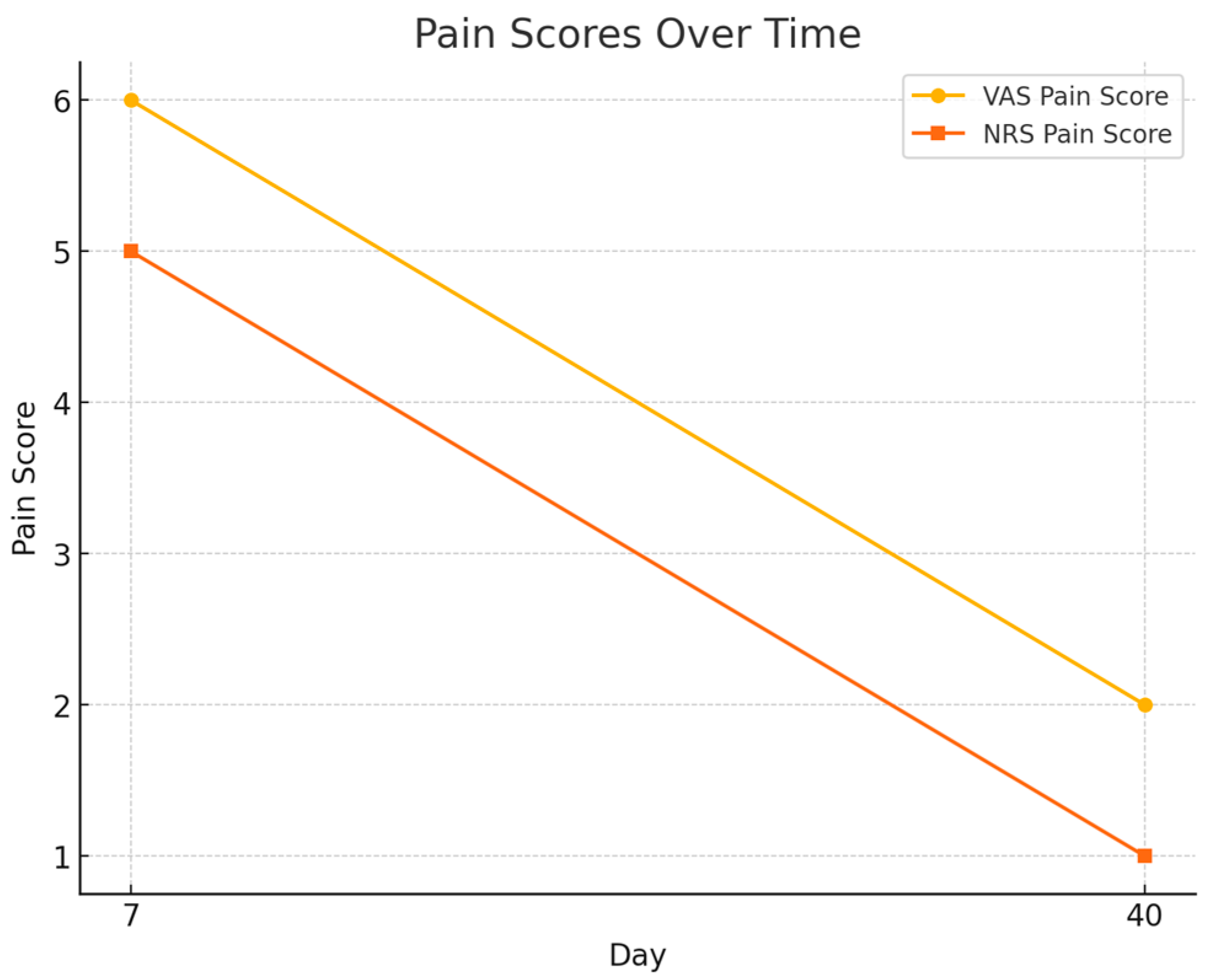

- VAS score decreased from 6.0 ± 1.5 at day 7 to 2.0 ± 0.9 at day 40.

- NRS score declined from 5.0 ± 1.4 to 1.0 ± 0.8, both changes statistically significant (p < 0.001).

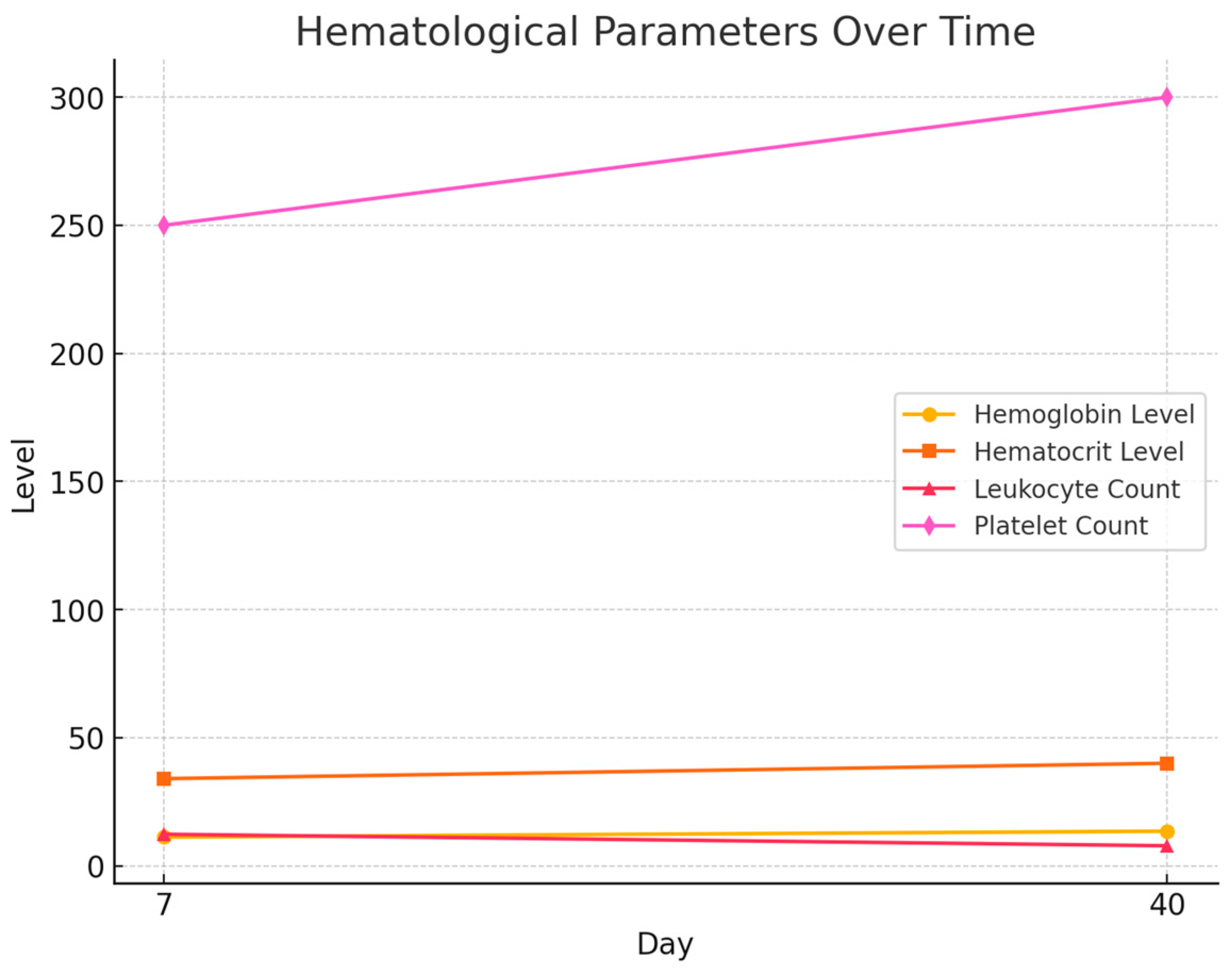

3.3. Hematological Dynamics

3.4. Correlation Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Originality and Innovative Contributions

- Implementation of a dual-stage intraoperative PRP administration protocol, targeting both the myometrial and subcutaneous layers.

- Use of six validated clinical scales (Manchester, POSAS, Vancouver, VAS, NRS, REEDA) to comprehensively assess scar morphology, vascularity, and patient-reported outcomes.

- Analysis of objective hematological markers (hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocytes, platelets) in relation to scar evolution, creating a unique link between systemic and local healing responses.

- Registration of the clinical protocol in an international database (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06978010), ensuring methodological transparency and ethical compliance.

4.2. Future Research Directions and Clinical Applicability

- Conduct larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with placebo or standard-care control arms to confirm causality and minimize bias.

- Evaluate long-term outcomes of scar remodeling, including elasticity, function, and the risk of hypertrophic or keloid scar formation.

- Standardize PRP preparation techniques and classify its biological profile (e.g., leukocyte-rich vs. leukocyte-poor), in line with PAW or DEPA classification systems.

- Explore the use of PRP in other gynecologic surgeries, such as myomectomy, hysterectomy, or endometriosis-related procedures, with tailored indications.

- Future studies should specifically evaluate women with a predisposition to keloid or hypertrophic scars, as this group may particularly benefit from PRP’s anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussen, I.; Worku, M.; Geleta, D.; Mahamed, A.A.; Abebe, M.; Molla, W.; Wudneh, A.; Temesgen, T.; Figa, Z.; Tadesse, M. Post-operative pain and associated factors after cesarean section at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod. Health Matters 2015, 23, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betrán, A.P.; Merialdi, M.; Lauer, J.A.; Thomas, J.; Van Look, P.; Wagner, M. Rates of Caesarean Section: Analysis of Global, Regional and National Estimates. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2007, 21, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, E.L.; Lundsberg, L.S.; Belanger, K.; Pettker, C.M.; Funai, E.F.; Illuzzi, J.L. Indications Contributing to the Increasing Cesarean Delivery Rate. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 118, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.D.; Hu, M.S.; Leavitt, T.; Barnes, L.A.; Lorenz, H.P.; Longaker, M.T. Cutaneous Scarring: Basic Science, Current Treatments, and Future Directions. Adv. Wound Care 2018, 7, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupak, A.; Kondracka, A.; Fronczek, A.; Kwaśniewska, A. Scar Tissue after a Cesarean Section-The Management of Different Complications in Pregnant Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, G.C.; Werner, S.; Barrandon, Y.; Longaker, M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008, 453, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound healing: A cellular perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Martin, P.; Tomic-Canic, M. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 265sr6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, M.; Madfes, D.C.; Lima, E.; Tian, Y.; Seité, S. Skin Care Management for Medical and Aesthetic Procedures to Prevent Scarring. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgos, M.S.; Pop, O.L.; Sandor, M.; Borza, I.L.; Negrean, R.A.; Cote, A.; Neamtu, A.A.; Grierosu, C.; Sachelarie, L.; Huniadi, A. Platelets Rich Plasma (PRP) Procedure in the Healing of Atonic Wounds. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amable, P.R.; Carias, R.B.V.; Teixeira, M.V.T.; da Cruz Pacheco, Í.; Corrêa do Amaral, R.J.F.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Borojevic, R. Platelet-rich plasma preparation for regenerative medicine: Optimization and quantification of cytokines and growth factors. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Zia, S.; Valbonesi, M.; Henriquet, F.; Venere, G.; Spagnolo, S.; Grasso, M.A.; Panzani, I. A new technique for hemodilution, preparation of autologous platelet-rich plasma and intraoperative blood salvage in cardiac surgery. Int. J. Artif. Organs 1987, 10, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.S.; Nouri, M.; Zarrabi, M.; Fatemi, M.J.; Shpichka, A.; Timashev, P.; Hassan, M.; Vosough, M. Platelet-Rich Plasma in Regenerative Medicine: Possible Applications in Management of Burns and Post-Burn Scars: A Review. Cell J. 2023, 25, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaichian, S.; Mirgaloybayat, S.; Tahermanesh, K.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Saadat Mostafavi, R.; Mehdizadehkashi, A.; Madadian, M.; Allahqoli, L. Effect of Autologous Platelet–Rich Plasma on Cesarean Section Scar; A Randomized, Double-Blinded Pilot Study. Shiraz E-Med. J. 2022, 23, e114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranian, A.; Esfehani-Mehr, B.; Pirjani, R.; Rezaei, N.; Sadat Heidary, S.; Sepidarkish, M. Application of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) on Wound Healing After Caesarean Section in High-Risk Patients. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e34449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhao, J.; Ren, Q.; Ma, Y.; Duan, P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S. Clinical application of platelet rich plasma to promote healing of open hand injury with skin defect. Regen. Ther. 2024, 26, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, C.; Baldino, J.; Bell, R.; Ramji, A.; Uyeki, C.; Mazzocca, A. Platelet-Rich Plasma: Review of Current Literature on its Use for Tendon and Ligament Pathology. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X. Platelet-rich plasma accelerates skin wound healing by promoting re-epithelialization. Burn. Trauma 2020, 8, tkaa028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, R.S.; Schwarz, E.M.; Maloney, M.D. Platelet-rich plasma therapy-future or trend? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, J. Introduction of a pilot study. Korean J. Anesth. 2017, 70, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausang, E.; Floyd, H.; Dunn, K.W.; Orton, C.I.; Ferguson, M.W.J. A New Quantitative Scale for Clinical Scar Assessment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draaijers, L.J.; Tempelman, F.R.; Botman, Y.A.M.; Tuinebreijer, W.E.; Middelkoop, E.; Kreis, R.W.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: A Reliable and Feasible Tool for Scar Evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1960–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, T.; Smith, J.; Kermode, J.; McIver, E.; Courtemanche, D.J. Rating the Burn Scar. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 66, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskisson, E.C. Measurement of Pain. Lancet 1974, 2, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Karoly, P.; Braver, S. The Measurement of Clinical Pain Intensity: A Comparison of Six Methods. Pain 1986, 27, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T. REEDA: Evaluating Postpartum Healing. J. Nurse Midwifery 1974, 19, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chueh, K.S.; Huang, K.H.; Lu, J.H.; Juan, T.J.; Chuang, S.M.; Lin, R.J.; Lee, Y.C.; Long, C.Y.; Shen, M.C.; Sun, T.W.; et al. Therapeutic Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma Improves Bladder Overactivity in the Pathogenesis of Ketamine-Induced Ulcerative Cystitis in a Rat Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, P.; Onishi, K.; Jayaram, P.; Lana, J.F.; Mautner, K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: New Performance Understandings and Therapeutic Considerations in 2020. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, P.; Lana, J.F.; Alexander, R.W.; Dallo, I.; Kon, E.; Ambrach, M.A.; van Zundert, A.; Podesta, L. Profound Properties of Protein-Rich, Platelet-Rich Plasma Matrices as Novel, Multi-Purpose Biological Platforms in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736 (2018, Reaffirmed/Updated): Optimizing Postpartum Care. Key Points: Initial Contact Within 3 Weeks; Ongoing Care; Comprehensive Visit by 12 Weeks; References WHO Schedule at 3 Days, 1–2 Weeks, and 6 Weeks. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/05/optimizing-postpartum-care (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- WHO (2013) Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn: At Least Three Contacts: Day 3 (48–72 h), Days 7–14, and at 6 Weeks (42 Days). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506649 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Middleton, K.K.; Barro, V.; Muller, B.; Terada, S.; Fu, F.H. Evaluation of the effects of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy involved in the healing of sports-related soft tissue injuries. Iowa Orthop. J. 2012, 32, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Barwijuk, M.; Pankiewicz, K.; Galas, A.; Nowakowski, F.; Gumula, P.; Jakimiuk, A.J.; Issat, T. The Impact of Platelet- Rich- Plasma Application during Caesarean Section on Wound Healing and Postoperative Pain: A Single-Blind Placebo-Controlled Intervention Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstee, D.J. The Relationship between Blood Groups and Disease. Blood Rev. 2010, 24, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, M.; Salter, A.; Tape, N.; Wilkinson, C.; Turnbull, D. Women’s Psychosocial Outcomes Following an Emergency Caesarean Section: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziętek, M.; Świątkowska-Feund, M.; Ciećwież, S.; Machałowski, T.; Szczuko, M. Uterine Cesarean Scar Tissue—An Immunohistochemical Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S.; Nobuta, Y.; Hanada, T.; Takebayashi, A.; Inatomi, A.; Takahashi, A.; Amano, T.; Murakami, T. Prevalence, Definition, and Etiology of Cesarean Scar Defect and Treatment of Cesarean Scar Disorder: A Narrative Review. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2023, 22, e12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debras, E.; Capmas, P.; Maudot, C.; Chavatte-Palmer, P. Uterine Wound Healing after Caesarean Section: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 296, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, A.; Koide, M. Adverse Events Related to Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy: A Systematic Review. Regen. Ther. 2024, 26, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xing, F.; Yan, T.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F. The Efficiency and Safety of Platelet-Rich Plasma Dressing in the Treatment of Chronic Wounds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, E.; Filardo, G.; Delcogliano, M.; Presti, M.L.; Russo, A.; Bondi, A.; Di Martino, A.; Cenacchi, A.; Fornasari, P.M.; Marcacci, M. Platelet-rich plasma: New clinical application: A pilot study for treatment of jumper’s knee. Injury 2009, 40, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Alimohamadi, Y.; Janani, M.; Hejazi, P.; Kamali, M.; Goodarzi, A. Platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of scars, to suggest or not to suggest? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 16, 875–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.9 ± 6.1 (range 18–40) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 4.5 (range 19.5–42.1) |

| Primiparous | 26 (54%) |

| Previous cesarean deliveries | 14 (27%) |

| Previous vaginal deliveries | 10 (19%) |

| Day | Scar Score Mean | Std Dev Scar Score | VAS Pain Score | NRS Pain Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 8.88 | 2.13 | 6 | 5 |

| 40 | 6.46 | 1.23 | 2 | 1 |

| Scale | Day 7 (Mean ± SD) | Day 40 (Mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester Scar Scale (MSS) | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) | 32.5 ± 6.0 | 21.4 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) | 8.1 ± 2.1 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | <0.01 |

| REEDA Scale (Redness, Edema, Ecchymosis, Discharge, Approximation) | 7.8 ± 2.0 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Day | Hemoglobin (g/dL) Level Mean | Hematocrit (%) Level Mean | Leukocyte (Cells/dL) Count Mean | Platelet (Cells/dL) Count Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 11.2 g/dL | 34% | 12,300/dL | 250.000/dL |

| 40 | 13.5 g/dL | 40% | 7800/dL | 300.000/dL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brezeanu, A.-M.; Brezeanu, D.; Stase, S.; Chirila, S.; Tica, V.-I. Intraoperative Platelet-Rich Plasma Application Improves Scar Healing After Cesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222905

Brezeanu A-M, Brezeanu D, Stase S, Chirila S, Tica V-I. Intraoperative Platelet-Rich Plasma Application Improves Scar Healing After Cesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222905

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrezeanu, Ana-Maria, Dragoș Brezeanu, Simona Stase, Sergiu Chirila, and Vlad-Iustin Tica. 2025. "Intraoperative Platelet-Rich Plasma Application Improves Scar Healing After Cesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222905

APA StyleBrezeanu, A.-M., Brezeanu, D., Stase, S., Chirila, S., & Tica, V.-I. (2025). Intraoperative Platelet-Rich Plasma Application Improves Scar Healing After Cesarean Section: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare, 13(22), 2905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222905