Medically Tailored Meals: A Case for Federal Policy Action

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

3. Results

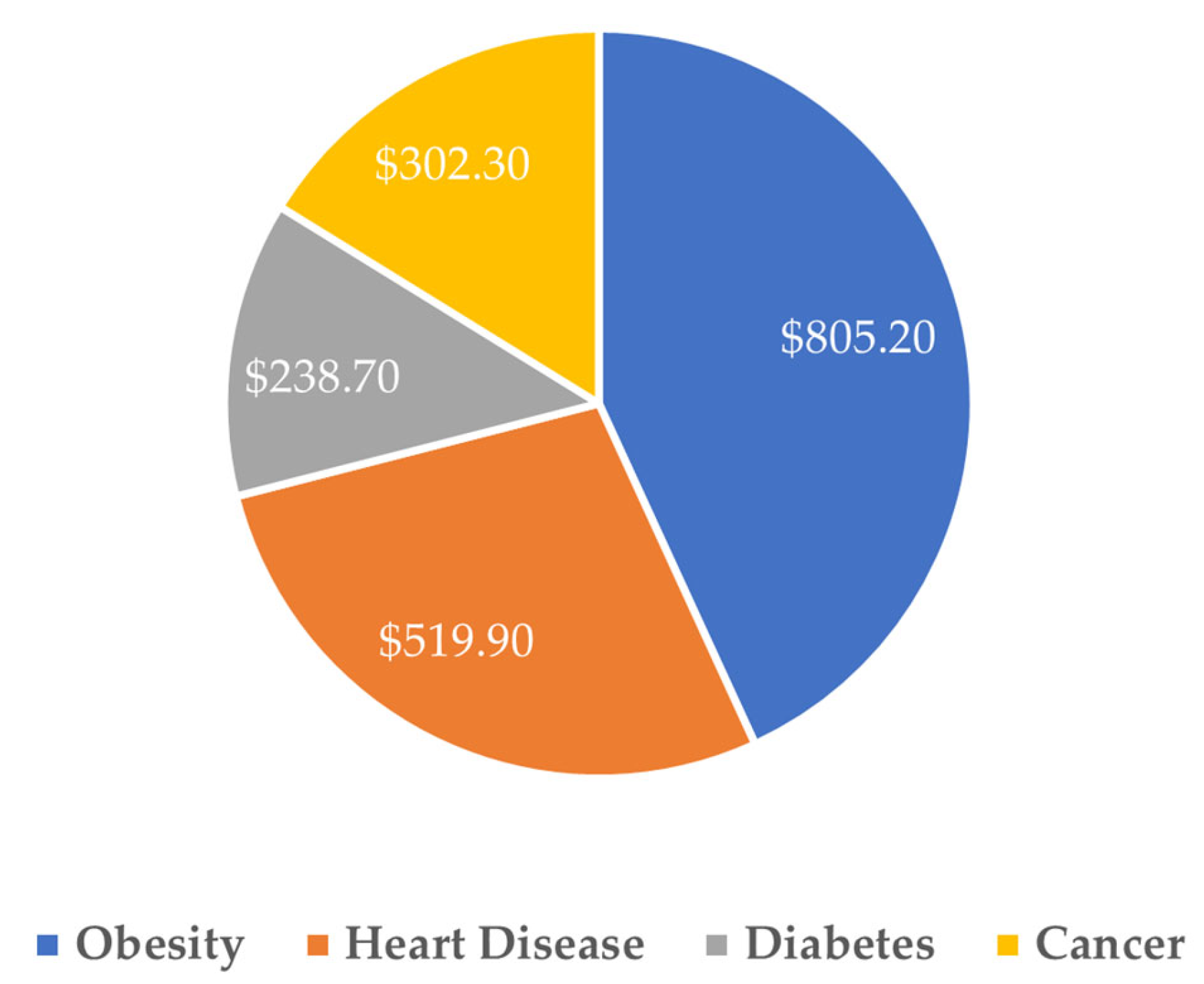

3.1. Cost Savings of Medically Tailored Meals

3.2. Clinical, Observational and Health Policy Modeling Evidence for Medically Tailored Meals

3.3. Barriers to Medically Tailored Meals Access

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Solutions to Leverage the Clinical and Cost Advantages of Medically Tailored Meals

4.1.1. Medicare FFS Demonstration for MTM

- Eligible beneficiaries: Eligible beneficiaries would include those who: (1) have one or more chronic disease(s); (2) are post-discharge; (3) are at risk for entering an institutional care setting; and/or (4) have limitations in activities of daily living (ADL).

- Eligible providers: Eligible providers would include inpatient and outpatient hospitals, as well as clinical group practices that have performed well historically in Medicare quality programs.

- Quality measures: Quality measures would assess reductions in: (1) all-cause inpatient admissions; (2) all-cause inpatient readmissions; (3) ED visits; and (4) post-acute institutional care.

- Cost measures: A cost measure would assess the reduction in total cost-of-care.

- Adherence to national nutrition guidelines: Home-delivered MTMs would have to adhere with the current and future Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which reflect standards for high-quality nutrition [36].

- No or minimal cost-sharing: Beneficiaries would not have any cost-sharing obligations for the home-delivered MTMs provided in the model or, in the alternative, may have modest cost sharing obligations, in order to encourage the widest possible participation to ensure a true test of the model.

- Awareness: By launching the program with providers instead of managed care plans, awareness among providers would be necessary, which would lead to greater member awareness. In addition to training, availability of information about MTM programs in provider electronic health records would further facilitate awareness of and timely discussions about, and patient referrals into, available MTM programs.

4.1.2. Medicare Advantage High-Value FIM Benefit Model

- High-value benefit design: MA plans would work with contracted food providers to offer home-delivered MTMs and/or other FIM solutions that adhere to national nutrition standards (the current and future Dietary Guidelines for Americans) to at-risk MA enrollee populations at little or no cost at durations that extend beyond the current MA supplemental or Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill limitations.

- Eligible beneficiaries: Beneficiaries electing to receive FIM benefit could include those who: (1) have one or more chronic disease(s); (2) are dual-eligible; (3) are post-discharge; (4) are at risk for entering an institutional care setting; and/or (5) have ADL limitations.

- Value assessment: MA plans and Medicare would share in savings from reductions in total cost-of-care spending. Quality measures would assess reductions in: (1) all-cause inpatient admissions; (2) all-cause inpatient readmissions; (3) ED visits; and (4) post-acute institutional care.

4.1.3. Use of FIM Benefits in Current CMMI Models

- Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) Model: TMaH supports state Medicaid agencies in delivering whole-person maternity care by addressing physical, mental, and social needs during pregnancy. Participating states could incorporate home-delivered MTMs as part of care plans to improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

- Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP): Under the MSSP, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) can provide in-kind services such as meal programs to improve patient outcomes as part of broader care coordination to effectively manage chronic disease.

- ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model: In ACO REACH, providers can offer home-delivered MTMs as in-kind service to advance patient care.

- Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM): Under TEAM, acute care hospitals have responsibility for cost and quality of care for 30 days following a Medicare FFS patient undergoing one of five types of surgical procedures. All TEAM-participating hospitals could ensure that post-discharge patients have access to home-delivered MTMs to improve health outcomes and lower total costs.

- Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (MDPP) Expanded Model: The MDPP gives beneficiaries with prediabetes access to structured individual and group interventions with the goal of preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes. Providing home-delivered MTMs would complement the overall strategy of the model to engage the at-risk beneficiary in better managing his health to prevent type 2 diabetes onset.

- Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM): EOM providers can offer home-delivered MTMs as in-kind services to improve health outcomes and the overall care experience for beneficiaries with cancer participating in the model.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FFS | Fee-for-service |

| MTM | Medically tailored meal |

| MA | Medicare Advantage |

| FIM | Food-is-medicine |

| CMMI | Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation |

| RD | Registered dietitian |

| ED | Emergency department |

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| MSSP | Medicare shared savings program |

| ACO | Accountable Care Organizations |

| REACH | Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health Model |

| TEAM | Transforming Episode Accountability Model |

| MDPP | Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program Expanded Model |

| EOM | Enhancing Oncology Model |

| TMaH | Transforming Maternal Health Model |

References

- Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- The Economic Costs of Poor Nutrition. Available online: https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-economic-costs-of-poor-nutrition/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Equity and the Costs of Chronic Disease: Who’s Impacted the Most? Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/the-inequities-in-the-cost-of-chronic-disease-why-it-matters-for-older-adults/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Combatting Senior Malnutrition. Available online: https://acl.gov/news-and-events/acl-blog/combatting-senior-malnutrition (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Spotlight on Senior Health: Adverse Health Outcomes of Food Insecure Older Americans. Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/research/senior-hunger-research/or-spotlight-on-senior-health-executive-summary.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Basu, S.; Gundersen, C.; Seligman, H.K. State-level and county-level estimates of health care costs associated with food insecurity. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Do Medicare Beneficiaries Value About Their Coverage? Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2024/feb/what-do-medicare-beneficiaries-value-about-their-coverage (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Next Steps in Chronic Care: Expanding Innovative Medicare Benefits. Available online: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Next-Steps-in-Chronic-Care.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Randall, L.; Cranston, K.; Waters, D.B.; Hsu, J. Association between receipt of a medically tailored meal program and health care use. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mom’s Meals, AmeriHealth Caritas District of Columbia Food as Medicine Programs Reduce Health Care Costs and Readmissions. Available online: https://www.momsmeals.com/our-newsroom/moms-meals-amerihealth-caritas-district-of-columbia-food-as-medicine-programs-reduce-health-care-costs-and-readmissions/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Hill, C.; Ajayi, T.; Linsky, T.; Tishler, L.W.; DeWalt, D.A. Meal delivery programs reduce the use of costly health care in dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.L.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr.; Rauschenback, F.; Roe, D.A. Home-delivered meals benefit the diabetic elderly. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1993, 93, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurvey, J.; Rand, K.; Daugherty, S.; Dinger, C.; Schmeling, J.; Laverty, N. Examining health care costs among MANNA clients and a comparison group. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2013, 4, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, K.; Cudhea, F.P.; Wong, J.B.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Downer, S.; Lauren, B.N.; Mozaffarian, D. Association of national expansion of insurance coverage of medically tailored meals with estimated hospitalizations and health care expenditures in the US. JAMA Net. Open 2022, 5, e2236898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Hager, K.; Wang, L.; Cudhea, F.P.; Wong, J.B.; Kim, D.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Estimated impact of medically tailored meals on health care use and expenditures in 50 US states: Article examines the impact of medically tailored meals on health care use and expenditures in 50 US states. Health Aff. 2025, 44, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.N.; Miles, R.; Alejandro-Rodriguez, M.; Gorenflo, M.P.; Misirang, A.; Barbarotta, S.; Phillips, W.; Bharmal, N.; Yepes-Rios, M. Feasibility of self-investment in a medically tailored meals program by a large health enterprise: Cleveland Clinic experience. Nutr. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palar, K.; Napoles, T.; Hufstedler, L.L.; Seligman, H.; Hecht, F.M.; Madsen, K.; Ryle, M.; Pitchford, S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Weiser, S.D. Comprehensive and medically appropriate food support is associated with improved HIV and diabetes health. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically tailored meal delivery for diabetes patients with food insecurity: A randomized cross-over trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, J.L.; Racine, E.F.; Ngugi, G.W.; McAuley, W.J. The effect of home-delivered Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) meals on the diets of older adults with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin Gleason, J.; Lundburg Bourdet, K.; Koehn, K.; Holay, S. Cardiovascular risk reduction and dietary compliance with a home-delivered diet and lifestyle modification program. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, C.N.; Hart, B.B.; McNeil, C.K.; Duerr, J.M.; Weller, G.B. Improved time in range during 28 days of meal delivery for people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2022, 35, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, L.M.; Fang, H.Y.; Ashrafi, S.A.; Burrows, B.T.; King, A.C.; Larsen, R.J.; Sutton, B.P.; Wilund, K.R. Pilot study to reduce interdialytic weight gain by provision of low-sodium, home-delivered meals in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial. Int. 2021, 25, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E.; Baki, J.; Nikirk, S.; Hummel, S.; Asrani, S.K.; Lok, A. Medically tailored meals for the management of symptomatic ascites: The SALTYFOOD pilot randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 8, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Duan, L.; Lee, J.S.; Winn, T.G.; Arakelian, A.; Akiyama-Ciganek, J.; Huynh, D.N.; Williams, D.D.; Han, B. Association of a medicare advantage posthospitalization home meal delivery benefit with rehospitalization and death. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e231678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S.L.; Karmally, W.; Gillespie, B.W.; Helmke, S.; Teruya, S.; Wells, J.; Trumble, E.; Jimenez, O.; Marolt, C.; Wessler, J.D.; et al. Home-delivered meals postdischarge from heart failure hospitalization. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e004886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Connelly, N.; Parsons, C.; Blackstone, K. Simply delivered meals: A tale of collaboration. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.S.; Mor, V. Providing more home-delivered meals is one way to keep older adults with low care needs out of nursing homes. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementation Considerations for Medically Tailored Meals: Summary of Expert Stakeholder Convening and Policy Recommendations. Available online: https://fimcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/FIMC-Tufts-FollowUpCMS-CMMI-Final.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Plans Generally Offered Some Supplemental Benefits, but CMS Has Limited Data on Utilization. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/d23105527.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Campbell, A.D.; Godfryd, A.; Buys, D.R.; Locher, J.L. Does Participation in Home-Delivered Meals Programs Improve Outcomes for Older Adults? Results of a Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 34, 124–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicaid Long Term Services and Supports Annual Expenditures Report. Available online: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/downloads/ltssexpenditures2020.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ridberg, R.; Sharib, J.R.; Garfield, K.; Hanson, E.; Mozaffarian, D. ‘Food is medicine’ in the US: A national survey of public perceptions of care, practices, and policies. Health Aff. 2025, 4, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.2133—Medically Tailored Home-Delivered Meals Demonstration Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2133/cosponsors (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 8816 Offered by Mr. Smith of Missouri. Available online: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/WM/WM00/20240627/117491/BILLS-118-HR8816-S001195-Amdt-3.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- McGovern, Malliotakis Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Address Link Between Diet and Chronic Disease. Available online: https://mcgovern.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=400249 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

| Program Type | Study Design | Population | Sample Size | Meals Protocol | Duration | Selected Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Care | Observational cohort | Dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid adults | 133 medically tailored meals recipients with 1002 controls; 624 non-tailored with 1318 controls | Medically tailored meals: 2 meals + snacks/day, 5 days/week; Non-tailored: 2 meals/day, 5 days/week | 6 months | Medically tailored meals: 70% fewer emergency department visits, 52% fewer hospital admissions, 72% fewer emergency transports, net savings $220/month; Non-tailored: 44% fewer emergency department visits, 38% fewer emergency transports, no change in hospital admissions, net savings $10/month | [11] |

| Chronic Care | Retrospective cohort | State of Massachusetts citizens with chronic conditions and data in the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims database | 499 medically tailored meals recipients, 521 nonrecipients | 10 medically tailored meals/week (2/day, 5 days/week), tailored to medical needs | Average of 12 months (median 9 month) | 49% fewer hospital admissions (incidence rate ratio 0.51); 72% fewer skilled nursing admissions (incidence rate ratio 0.28); $753 lower monthly spending (16% reduction) | [9] |

| Chronic Care | Quasi-experimental | Elderly adults with diabetes in New York State | 79 meal recipients; 75 controls | Home-delivered meals daily (3/day, 7 days/week) | Ongoing | Recipients had lower food insecurity (p < 0.02), better dietary adherence, less uncontrolled diabetes (22% vs. 52%, p = 0.03), and fewer hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes (7% vs. 23%, p = 0.09) | [12] |

| Chronic Care | Pilot cohort | Chronically ill adults with HIV/AIDS, cancer, renal disease, etc., in Philadelphia | 65 Metropolitan Area Neighborhood Nutrition Alliance clients; 633 controls | 3 tailored meals/day, 7 days/week, with nutrition counseling | ≥3 months; outcomes tracked over 12 months | Lower monthly costs ($28,268 vs. $40,906, p < 0.001); 37% shorter hospital stays (10.7 vs. 17.1 days); fewer inpatient visits (0.2 vs. 0.4, p < 0.001); 93% discharged home vs. 72% (p < 0.001) | [13] |

| Chronic Care | Policy simulation model | U.S. adults with Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance, diet-sensitive condition + instrumental activity of daily living limitation | 6.3 million modeled eligible adults | 10 tailored meals/week (2/day, 5 days/week) | 8 months/year | 1 year: 1.59 million fewer hospitalizations, $13.6 billion net savings; 10 years: 18.3 million fewer hospitalizations, $185.1 billion net savings | [14] |

| Chronic Care | Policy simulation model | Adults with Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance; diet-sensitive condition + instrumental activity of daily living limitation | 10.4 million modeled eligible adults | 10 tailored meals/week (2/day, 5 days/week) | 8 months/year | 1 year: 2.6 million fewer hospitalizations, $23.7 billion savings; cost-saving in 49/50 states; 5 years: 10.8 million fewer hospitalizations, $111 billion in savings | [15] |

| Chronic Care | Single-arm feasibility cohort | Patients with chronic conditions | 60 participants analyzed | 14 frozen meals/week (2/day, 7 days/week) | 3 months | Decreased emergency department visits (1.7 → 1.2, p = 0.005); decreased inpatient days (5.1 → 3.2, p = 0.02); average cost savings $12,046; high satisfaction; no change in mental/physical health scores | [16] |

| Chronic Care | Prospective pre-post cohort | Adults with HIV and/or type 2 diabetes, low-income, food insecure | 72 participants; 52 completed with data | 3 medically tailored meals + snacks/day, 7 days/week, meeting 100% of daily nutritional needs | 6 months | Improved food security (very low: 60% → 12%); improve diet quality (reduced fat, improved fruits/veg); reduced depressive symptoms and binge drinking; reduced trade-offs between food and healthcare; HIV: improved antiretroviral therapy adherence (47% → 70%); Type 2 diabetes: reduced distress, improved self-management; HbA1c improved (not significant) | [17] |

| Chronic Care | Randomized cross-over trial | Adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes and food insecurity | 44 participants randomized; 42 completed | 10 tailored meals/week (2/day, 5 days/week), tailored for diabetes + comorbidities | 12 weeks with meals, 12 weeks without (cross-over) | Increased diet quality (healthy eating index + 31 points, p < 0.0001); decreased food insecurity (42% vs. 62%); decreased hypoglycemia (47% vs. 64%); increased mental health quality of life; HbA1c modestly lower (not significant) | [18] |

| Chronic Care | Randomized controlled trial | Adults ≥ 60 years with hypertension and/or hyperlipidemia | 210 participants analyzed (321 enrolled) | 7 Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension meals/week (1/day), delivered frozen with dietitian follow-up | 12 months | Increased intermediate Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension accordance (20% higher at 6 months, p = 0.001); increased saturated fat target compliance at 12 months (18% higher, p = 0.007); increased targets met for protein, fat, magnesium, potassium; gains stronger in whites and higher-income participants | [19] |

| Chronic Care | Prospective intervention trial | Adults with congestive heart disease | 35 participants analyzed | 3 heart-healthy meals + snacks daily (67% carb, 16% protein, 17% fat, 4% sat fat, 25 g fiber) + weekly dietitian phone education | 8 weeks | 91% adherence at 4 weeks, 88% at 8 weeks; decreased weight (−3.7 kg), decreased waist circumference (−2.0 inches), decreased LDL (−7.5 mg/dL), decreased total cholesterol (−7 mg/dL); improved diet quality and quality of life | [20] |

| Chronic Care | Prospective single arm trial | Adults with type 2 diabetes enrolled in a digital care program | Intervention: 154 enrolled (110 analyzed); Control: 203 (100 analyzed) | 3 meals/day, 7 days/week (pre-portioned diabetes-friendly meals; household member option) | 4 weeks | Time in range +6.8 points (56.1 → 62.9%; p < 0.001); estimated HbA1c −0.21 (p < 0.001); time above range −6.8 (p < 0.001); Difference-in-differences vs. control: +6.5, −0.18, −6.4, respectively; more participants achieved or maintained ≥70% time in range; effects diminished after meals ended | [21] |

| Chronic Care | Pilot prospective trial | Adults on maintenance hemodialysis | 20 participants analyzed | 3 meals lower in sodium, phosphorous and potassium | 4 weeks (after 4-week control period) | Reduction in interdialytic weight gain (−0.82 kg, p < 0.001); reduce sodium intake (−1687 mg, p < 0.001); reduce thirst, xerostomia; reduce systolic blood pressure (−18 mmHg, p < 0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (−6 mmHg, p = 0.008); reduce plasma phosphorus; reduce volume overload; no change in serum/tissue sodium | [22] |

| Chronic Care | Randomized controlled trial | Adults with cirrhosis and symptomatic ascites | 40 randomized, 20 received medically tailored meals, 20 received standard of care (low-sodium diet education handout) | 3 low-sodium, high-protein meals/day + evening protein supplement | 4 weeks meals, 12 weeks follow-up | Reduction in paracenteses (0.34 vs. 0.45/week); intervention group had fewer hospital days (0.62 vs. 1.04/week), lower diuretic escalation; increased ascites-specific quality of life (+25% vs. +13%); deaths: 2 vs. 4; 1 transplant in intervention arm | [23] |

| Post-Discharge | Comparative cohort | Medicare Advantage members ≥65, post-hospitalization for heart failure or other acute conditions | Heart failure: 742 meals vs. 3289 controls; Non-heart failure: 756 meals vs. 7188 controls | 2–3 home-delivered meals/day, 7 days/week | Up to 4 weeks (56–84 meals) | Reduced 30-day mortality (odds ratio 0.37) and reduced composite rehospitalization + death vs. concurrent controls (odds ratio 0.55, p < 0.001). Non-heart failure: reduced 30-day mortality (odds ratio 0.26) and reduced composite events (odds ratio 0.48, p < 0.001); effects persisted at 60 days; time-to-readmission also improved (hazard ratio ~0.7) | [24] |

| Post-Discharge | Randomized controlled trial | Adults ≥ 55 discharged after acute decompensated heart failure | 66 randomized, 33 received Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension/Sodium-Reduced Diet, 33 received usual care | 3 Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension/Sodium-Reduced Diet meals/day + snacks, ~1500 mg sodium/day, tailored for comorbidities | 4 weeks meals, 12 weeks follow-up | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire summary (+13 vs. +10, p = 0.37); Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clinical trended better (+18 vs. +10, p = 0.053); 30-d heart failure rehospitalizations lower (3 vs. 11, p = 0.055); fewer days rehospitalized (17 vs. 55, p = 0.06); no major safety concerns | [25] |

| Post-Discharge | Time-series evaluation within care transition program | Medicare members designated as at high risk of readmission and part of a care transitions program | 622 Simply Delivered for Maine recipients | Weekly frozen specialized meals; up to 7 days/week supplied; first delivery ≤4 days post-discharge | 4 weeks post-discharge (within the care-transition period) | 30-day readmissions 10.3% (8.1–12.9); 16.3% lower vs. Community-based Care Transition Program-only 12.3% (10.0–15.2) and 38% lower vs. baseline 16.6% (13.8–19.7); estimated savings $212,160; program cost $43,540; return on investment 387% | [26] |

| Long-term Care | Policy simulation model | Adults ≥ 65 in Older Americans Act Title III-C2 programs (Meals on Wheels) | National model: ~393,000 added clients | Typically 1 meal/day, 5–7 days/week | Ongoing community support; model projects +1% expansion | 1% expansion → 0.2% reduced low-care nursing home residents; ~$109 million Medicaid savings (1722 avoided nursing home placements); 26 states saved (e.g., PA $5.7 million), 22 states incurred net costs; meal expansion cost $117.6 million | [27] |

| Access Gaps | |

|---|---|

| Medicare Fee-for Service | Medically tailored meals not covered as a Medicare Fee-for-Service benefit No supplemental benefits in Medicare Fee-for-Service |

| Medicare Advantage | Approximately 83% of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have access to medically tailored meals supplemental benefits Benefits are mostly limited to short duration post-discharge programs and utilization is unclear [29] |

| Medicaid Home and Community-Based Waivers | Not all waivers include medically tailored meals Meal utilization among waiver-eligible limited; care attendants time misaligned [27,30,31] |

| Medicaid (other) | Novel coverage pathways (Value-Added Benefit, In Lieu of Services and Settings, 1115 Waivers) are fragmented States require specialized knowledge, budget, review to implement novel waivers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macpherson, C.; Frist, W.H.; Gillen, E. Medically Tailored Meals: A Case for Federal Policy Action. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222899

Macpherson C, Frist WH, Gillen E. Medically Tailored Meals: A Case for Federal Policy Action. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacpherson, Catherine, William H. Frist, and Emily Gillen. 2025. "Medically Tailored Meals: A Case for Federal Policy Action" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222899

APA StyleMacpherson, C., Frist, W. H., & Gillen, E. (2025). Medically Tailored Meals: A Case for Federal Policy Action. Healthcare, 13(22), 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222899