Effectiveness of Blog Writing Intervention for Promoting Subjective Well-Being, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth of Palliative Care Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Operational Definitions of Study Terms

1.2. Conceptual Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

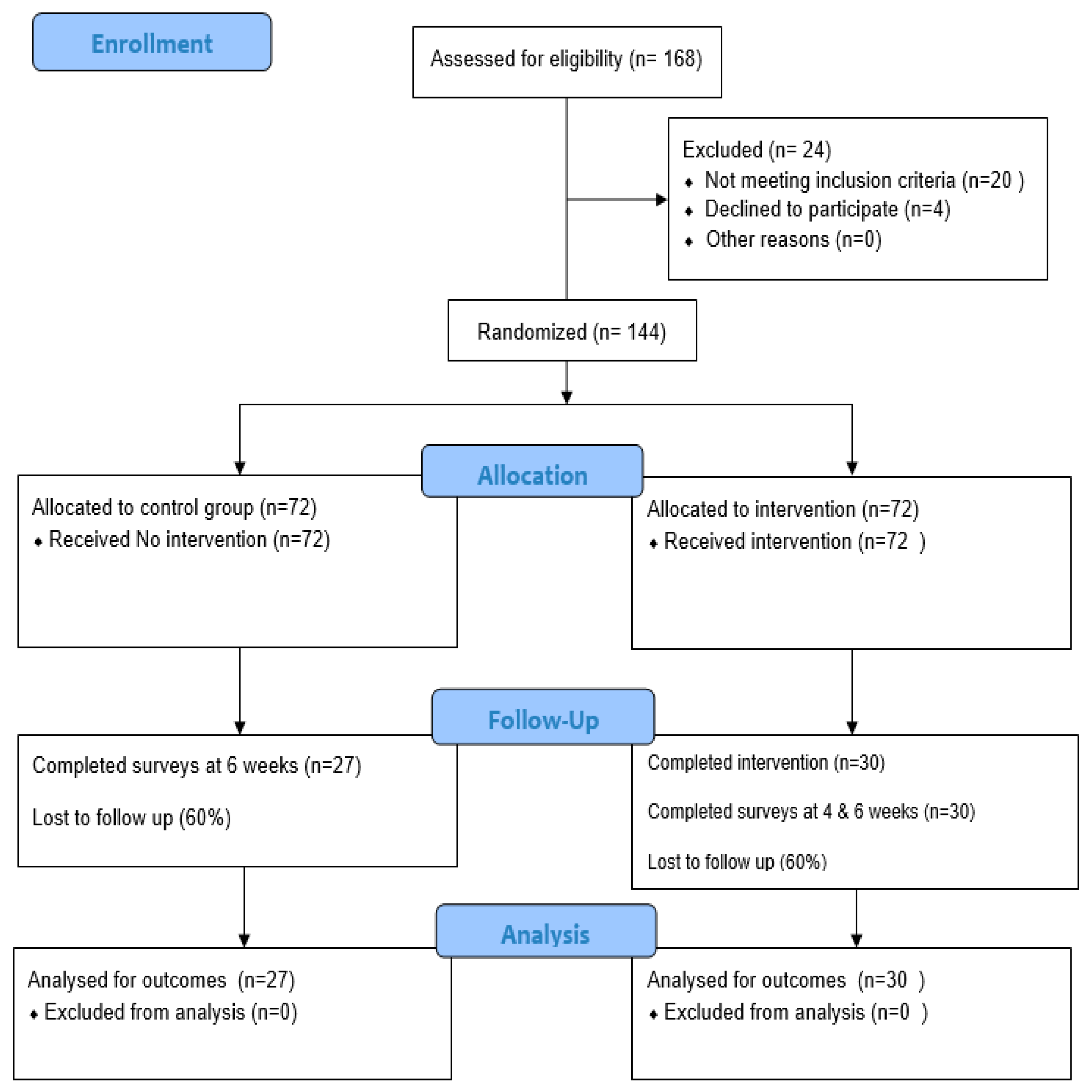

2.2. Sample and Recruitment

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Self-Reported Survey Measures

2.6. Procedure and Data Collection

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Variables

4.2. A Qualitative Analysis of the Blog Narratives: Given Below Are the Themes Generated from the Weekly Blog Narratives Completed by the Intervention Group

4.2.1. Self-Awareness and Reflection

I believe some healing took place and has continued in my understanding of past experiences and my work.

It allows me to think more calmly and deal with the trauma I have encountered, giving me a better meaning in life. it helped me heal the trauma am experiencing. Help me in stress relief, help me to better stabilize my emotions. Helped me reflect on my past which had a great effect on me. It helped make my time useful and helped me come out of this mess. Feel calm.

Writing about traumatic events can help ease the emotional stress of negative experiences… I feel good when I reflect on the trauma I’ve been through and connect and heal through SOPHIE.

4.2.2. Positive Attitude Towards Life

SOPHIE helped me to take responsibility for my thoughts, find meaning in trauma, stay open to myself, and develop new worldviews.

Helped me do a life review. I could reevaluate where some change is needed for better balance and happiness.

4.2.3. Find Meanings and Connections Within Self

Using SOPHIE made me feel vulnerable sometimes. Vulnerability is also a sign of courage. When we embrace who we are and how we feel, we become more resilient and braver.

Writing blogs made me strong and helped me to reevaluate my values and beliefs. it was a kind of therapeutic journal which I haven’t done in a while.

5. Discussion

Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANCOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BRS | Brief Resiliency Scale |

| IRB | Institutional Ethical Review Board |

| NPT | Nurses’ Psychological Trauma |

| PC | Palliative care |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| PTGI | Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory |

| RSL | Resilience |

| SOPHIE | Self-exploration on Ontological, Phenomenological, Humanistic, Ideological, and Existential |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SUBI | Subjective Well-Being Inventory |

| US | United States |

References

- Ogińska-Bulik, N. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth in nurses working in palliative care—The role of psychological resilience. Postepy Psychiatr. I Neurol. 2018, 27, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’malley, C.M. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornøe, K.A.; Danbolt, L.J.; Kvigne, K.; Sørlie, V. The challenge of consolation: Nurses’ experiences with spiritual and existential care for the dying-a phenomenological hermeneutical study. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S.; Pakpour, V.; Rahmani, A.; Wilson, M.; Feizollahzadeh, H. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among critical care nurses in Iran. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 31, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2762–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Yang, B.X.; Luo, D.; Liu, Q.; Ma, S.; Huang, R.; Lu, W.; Majeed, A.; Lee, Y.; Lui, L.M.; et al. The mental health effects of COVID-19 on health care providers in China. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 635–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanathan, P.; Lamb, D.; Scott, H.; Stevelink, S.; Greenberg, N.; Hotopf, M.; Morriss, R.; Raine, R.; Rafferty, A.M.; Madan, I.; et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviour among healthcare workers in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidambaram, P.; Garfield, R.; Neuman, T. COVID-19 Has Claimed the Lives of 100,000 Long-Term Care Residents and Staff. Available online: https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/covid-19-has-claimed-the-lives-of-100000-long-term-care-residents-and-staff/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Andhavarapu, S.; Yardi, I.; Bzhilyanskaya, V.; Lurie, T.; Bhinder, M.; Patel, P.; Pourmand, A.; Tran, Q.K. Post-traumatic stress in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amberson, T. Postpandemic Psychological Recovery and Emergency Nursing: Creating a narrative for change. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 47, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, K.J. A middle-range theory of nurses’ psychological trauma. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 45, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, K.J.; Reddick, B.; Zhang, L.; Krcelich, K. Nurses’ psychological trauma: “They leave me lying awake at night”. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, K.J.; Zhang, L.; Reddick, B. Predictors of substance use in registered nurses: The role of psychological trauma. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foli, K.J.; Thompson, J.R. The Influence of Psychological Trauma in Nursing; Sigma: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Foundation Survey Report Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: 2022 Workplace Survey. Nurses Not Feeling Heard, Ongoing Staffing and Workplace Issues Contributing to Unhealthy Work Environment. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/covid19/anf-2022-workforce-written-report-final.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Francis, M.E.; Pennebaker, J.W. Putting stress into words: The impact of writing on physiological, absentee, and self-reported emotional well-being measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 1992, 6, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, C.; Mortara, C.C. Writing technique across psychotherapies—From traditional expressive writing to new positive psychology interventions: A narrative review. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2021, 52, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, M.; Bürkner, P.-C.; Holling, H. Effects of expressive writing on depressive symptoms-A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2018, 25, e12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics XM Platform; Computer software; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Sagan, O. An interplay of learning, creativity and narrative biography in a mental health setting: Bertie’s story. In Art, Creativity and Imagination in Social Work Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Seagal, J.D. Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. J. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 55, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, A.; Grohol, J.M. Current and future trends in internet-supported mental health interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2011, 29, 155–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Snowden, M. SOPHIE (Self-Exploration Through Ontological, Phenomenological, Humanistic, Ideological and Existential Expressions): A Mentoring Framework. In Mentorship, Leadership, and Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Lalani, N. Approaching spiritual and existential care needs in health education: Applying SOPHIE (self-exploration through ontological, phenomenological, and humanistic, ideological, and existential expressions), as practice methodology. Religions 2020, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattis, J.; Rogers, M.; Ali, G.; Curran, S. Spiritually competent practice and cultural aspects of spirituality. In Advanced Practice in Nursing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, G.; Üstün, B.; Günüşen, N.P. Effect of a nurse-led intervention programme on professional quality of life and post-traumatic growth in oncology nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 24, e12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Computer Software. IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020.

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nima, A.; Cloninger, K.M.; Persson, B.N.; Sikström, S.; Garcia, D. Validation of subjective well-being measures using item response theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, I.; Hashim, N. A critical review of scales used in resilience research. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 19, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidmahmoodi, J.; Rahimi, C.; Mohamadi, N. Resiliency and religious orientation: Factors contributing to posttraumatic growth in Iranian subjects. Iran J. Psychiatry 2011, 6, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cresswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.; Rubin, D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Toole, J.O. Institutional storytelling and personal narratives: Reflecting on the ‘value’ of narrative inquiry. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2018, 37, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K. Stress, expressive writing, and working memory. In The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC USA, 2004; pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Blumberg, C.J. Disclosing trauma through writing: Testing the meaning-making hypothesis. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2002, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstad, G.L.; Giorgi, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Pandolfi, C.; Foti, G.; León-Perez, J.M.; Cantero-Sánchez, F.J.; Mucci, N. Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: A narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Conrad, D.; Evans, J.; Jooste, K.; Solyntjes, J.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. Feasibility and acceptability of a resilience training program for intensive care unit nurses. Am. J. Crit. Care 2014, 23, e97–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechard, E.; Evans, J.; Cho, E.; Lin, Y.; Kozhumam, A.; Jones, J.; Grob, S.; Glass, O. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of an online expressive writing intervention for COVID-19 resilience. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 45, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Meek, P. Factors affecting resilience and development of posttraumatic stress disorder in critical care nurses. Am. J. Crit. Care 2017, 26, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, G.; Üstün, B. Professional quality of life in nurses: Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 9, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hu, M.-L.; Song, Y.; Lu, Z.-X.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Wu, D.-X.; Xiao, T. Effect of positive psychological intervention on posttraumatic growth among primary healthcare workers in China: A preliminary prospective study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accoto, A.; Chiarella, S.G.; Raffone, A.; Montano, A.; de Marco, A.; Mainiero, F.; Rubbino, R.; Valzania, A.; Conversi, D. Beneficial effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on the well-being of a female sample during the first total lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.M.; Gillham, D.M. The experience of young adult cancer patients described through online narratives. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Characteristic | Total (N = 57) | Control Group (N = 27) | Intervention Group (N = 30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 53 | 93 | 26 | 96.3 | 28 | 93.3 |

| Male | 4 | 7 | 1 | 3.7 | 2 | 6.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 2 | 3.5 | 1 | 3.7 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Married/partnered | 53 | 93 | 26 | 96.3 | 24 | 80 |

| Divorced/widowed | 1 | 1.8 | - | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–28 | 3 | 5.3 | 1 | 3.7 | 2 | 6.7 |

| 29–39 | 40 | 70.2 | 18 | 66.7 | 21 | 70 |

| 40–50 | 12 | 21.1 | 8 | 29.6 | 6 | 20 |

| ≥62 | 1 | 1.8 | - | - | 1 | 3.3 |

| Nursing Education level | ||||||

| Associate degree | 9 | 15.8 | 9 | 33.3 | 11 | 36.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 48 | 84.2 | 18 | 66.7 | 19 | 63.3 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 55 | 96.5 | 22 | 81.5 | 30 | 100 |

| Employed part-time | 2 | 3.5 | 5 | 18.5 | - | - |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 6 | 10.5 | 6 | 22.2 | 2 | 6.7 |

| White | 51 | 89.5 | 21 | 77.8 | 28 | 93.3 |

| Ethnicity | 6 | 12 | ||||

| Hispanic | 3 | 5.3 | 3 | 11.1 | - | - |

| Non-Hispanic | 54 | 94.7 | 24 | 88.9 | 30 | 100 |

| Household Income | ||||||

| USD 35,000–USD 49,000 | 28 | 49.1 | 10 | 37 | 2 | 6.7 |

| USD 50,000–USD 74,999 | 20 | 35.1 | 16 | 59.3 | 2 | 6.7 |

| USD 75,000–USD 99,900 | 5 | 8.8 | 1 | 3.7 | 23 | 76.7 |

| Over USD 100,000 | 4 | 7 | - | - | 3 | 10 |

| Palliative Care Training | 53 | 93 | 27 | 100 | 29 | 96.7 |

| Mean Differences (MDs) Within Control Group (N = 27) | |||||||||||||

| Steps | PTGI | SUBI | BRS | ||||||||||

| MD | t | df | p | MD | t | df | p | Mean | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | |

| Step1: Pre/Post-6 weeks | −3.42 | −1.0 | 25 | 0.16 | 0.62 | −0.34 | 26 | 0.37 | −0.02 | −0.13 | 26 | 0.89 | −0.18/0.00370 |

| Mean Differences (MDs) Within Intervention group (N = 30) | |||||||||||||

| PTGI | SUBI | BRS | |||||||||||

| MD | t | df | p | MD | t | df | p | MD | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | |

| Step2: Pre/Post-4 weeks | −1.6 | −0.33 | 29 | 0.37 | −0.07 | 2.58 | 28 | 0.001 * | 0.24 | 2.45 | 29 | 0.02 * | −0.060/0.0037 |

| Step 3: Post-4 weeks–Post-6 weeks | 2.86 | 1.23 | 29 | 0.11 | 1.10 | 3.97 | 28 | 0.001 * | −0.02 | −0.13 | 26 | 0.89 | 0.225/0.0496 |

| Step 4: Pre/Post-week 6 | 1.27 | 0.29 | 29 | 0.38 | 1.73 | 6.72 | 28 | 0.008 * | 0.18 | −0.81 | 29 | 0.17 | 0.053/0.0029 |

| Step 5: Mean Differences (MDs) Between Groups | MD (SD) | t (df) | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTGI—Intervention | 72.11(9.79) | 0.751 (52) | 0.456 | 0.205/0.011 |

| Control | 69.92 (11.55) | |||

| BRS—Intervention | 3.03 (0.314) | −0.093 (55) | 0.927 | −0.025/0.0002 |

| Control | 3.04 (0.48) | |||

| SUBI—Intervention | 2.43 (1.16) | −4.83 (49) | <0.001 * | 1.279/0.323 |

| Control | 3.67 (0.73) |

| Outcomes | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | η2p (Effect Size) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTGI | ||||||

| Age | 719.88 | 1 | 719.88 | 3.45 | 0.06 | 0.050 |

| Income | 542.99 | 1 | 542.99 | 2.60 | 0.11 | 0.039 |

| Clinical area | 499.72 | 1 | 499.72 | 2.39 | 0.12 | 0.036 |

| Years as RN | 91.02 | 1 | 91.02 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.007 |

| Designation at work | 9.70 | 1 | 9.70 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.001 |

| Years in palliative care | 164.64 | 1 | 164.64 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.012 |

| Time of measurement | 530.80 | 1 | 530.80 | 2.54 | 0.11 | 0.038 |

| Total | 19,501.44 | 77 | ||||

| R-squared = 0.305 (adjusted R-squared = 0.176) | ||||||

| Subjective Well-Being | ||||||

| Age | 23.75 | 1 | 23.75 | 1.73 | 0.19 | 0.025 |

| Income | 12.59 | 1 | 12.59 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 0.013 |

| Clinical area | 19.75 | 1 | 19.75 | 1.44 | 0.23 | 0.021 |

| Years as RN | 8.76 | 1 | 8.76 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.009 |

| Designation at work | 31.50 | 1 | 31.50 | 2.30 | 0.13 | 0.033 |

| Years in palliative care | 86.67 | 1 | 86.67 | 6.34 | 0.01 * | 0.085 |

| Time of measurement | 96.18 | 1 | 96.18 | 7.03 | 0.01 * | 0.094 |

| Total | 1328.000 | 80 | ||||

| R-squared = 0.300 (adjusted R-squared = 0.177) | ||||||

| Resilience | ||||||

| Age | 0.38 | 1 | 0.38 | 1.41 | 0.23 | 0.020 |

| Income | 0.12 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.007 |

| Clinical area | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.001 |

| Years as RN | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.010 |

| Designation at work | 0.42 | 1 | 0.42 | 1.57 | 0.21 | 0.022 |

| Years in palliative care | 0.000 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.98 | 0.000 |

| Time of measurement | 1.17 | 1 | 1.17 | 4.39 | 0.04 * | 0.060 |

| Total | 20.985 | 81 | ||||

| R-squared = 0.117 (adjusted R-squared = −0.037) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lalani, N.; Ali, G.; Hamash, K.; Jimenez Paladines, A.I. Effectiveness of Blog Writing Intervention for Promoting Subjective Well-Being, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth of Palliative Care Nurses. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212757

Lalani N, Ali G, Hamash K, Jimenez Paladines AI. Effectiveness of Blog Writing Intervention for Promoting Subjective Well-Being, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth of Palliative Care Nurses. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212757

Chicago/Turabian StyleLalani, Nasreen, Gulnar Ali, Kawther Hamash, and Aracely Ines Jimenez Paladines. 2025. "Effectiveness of Blog Writing Intervention for Promoting Subjective Well-Being, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth of Palliative Care Nurses" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212757

APA StyleLalani, N., Ali, G., Hamash, K., & Jimenez Paladines, A. I. (2025). Effectiveness of Blog Writing Intervention for Promoting Subjective Well-Being, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth of Palliative Care Nurses. Healthcare, 13(21), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212757