Workplace Impact of Menopause Symptoms Among Canadian Women Physicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

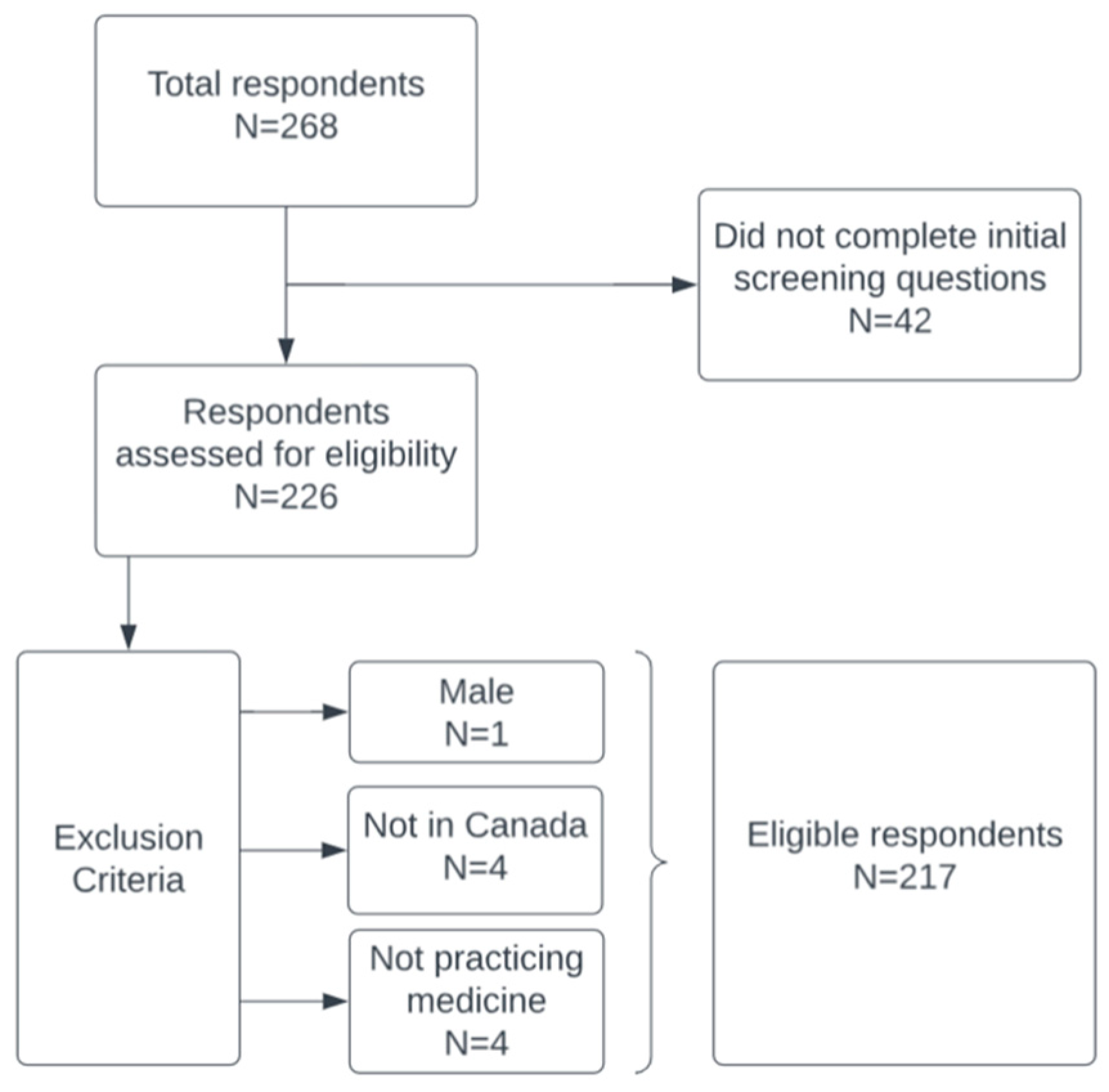

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Outcomes and Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Workplace and Practice Characteristics

3.3. Menopausal Symptoms and MHT Use

3.4. Impact of Menopausal Transition on Work

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

3.6. Qualitative Findings

- “I have sought out physicians and other resources for perimenopause but they are difficult to find even as a physician who knows the system”

- “The worst was not being taken seriously by my own family doctor of more than 20 years”

- “I suffered through the symptoms despite reaching out to my male GP about it. HRT was not offered until a few months ago when I saw a OBGYN for post-menopausal bleeding. After testing [was] normal, she offered HRT and I feel great. My sexual symptoms resolved, [I] sleep very well, and ‘arthritic’ pain disappeared.”

- “I am sure directors and colleagues seldom know about personal medical or menopausal issues. I don’t share because I am sure it would be viewed as a weakness.”

- “Generally something that women are expected to “tolerate”—Would not be understood or accommodated by men in my department.”

- “I had no idea how bad it can get. We need so much more education about this issue.”

- “It’s worse than most people acknowledge”

- “I had no idea that sleep disturbance would so profoundly affect me or be so difficult to treat.”

- “Tough it out is the way to go and just deal with it. There are far more challenging disabilities that others deal with.”

- “It was a very easy experience and keeping working helped.”

- “I think menopause was freeing experience for me. My symptoms were mild and I enjoy the lack of monthly cycle of pain and mood changes.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costanian, C.; McCague, H.; Tamim, H. Age at natural menopause and its associated factors in Canada: Cross-sectional analyses from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Menopause 2018, 25, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, N.; Evaniuk, D.; Huang, L.; Malhotra, U.; Blake, J.; Wolfman, W.; Fortier, M. Guideline No. 422a: Menopause: Vasomotor Symptoms, Prescription Therapeutic Agents, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Nutrition, and Lifestyle. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021, 43, 1188–1204.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avis, N.E.; Crawford, S.L.; Greendale, G.; Bromberger, J.T.; Everson-Rose, S.A.; Gold, E.B.; Hess, R.; Joffe, H.; Kravitz, H.M.; Tepper, P.G.; et al. Duration of Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms Over the Menopause Transition. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, M.K.; Shirreff, L. Hot flash: Experiencing menopause in medicine. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2022, 194, E1091–E1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, S. Menopause and the NHS: Caring for and retaining the older workforce. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartoulla, P.; Bell, R.J.; Worsley, R.; Davis, S.R. Menopausal vasomotor symptoms are associated with poor self-assessed work ability. Maturitas 2016, 87, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.; MacLennan, S.J.; Hassard, J. Menopause and work: An electronic survey of employees’ attitudes in the UK. Maturitas 2013, 76, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riach, K.; Rees, M. Diversity of menopause experience in the workplace: Understanding confounding factors. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2022, 27, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammam, R.A.M.; Abbas, R.A.; Hunter, M.S. Menopause and work—The experience of middle-aged female teaching staff in an Egyptian governmental faculty of medicine. Maturitas 2012, 71, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geukes, M.; van Aalst, M.P.; Robroek, S.J.W.; Laven, J.S.E.; Oosterhof, H. The impact of menopause on work ability in women with severe menopausal symptoms. Maturitas 2016, 90, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J.; Qin, M.; Vlachantoni, A. Menopausal transition and change in employment: Evidence from the National Child Development Study. Maturitas 2021, 143, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, M.; Bitzer, J.; Cano, A.; Ceausu, I.; Chedraui, P.; Durmusoglu, F.; Erkkola, R.; Geukes, M.; Godfrey, A.; Goulis, D.G.; et al. Global consensus recommendations on menopause in the workplace: A European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) position statement. Maturitas 2021, 151, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menopause Foundation of Canada. Menopause and Work in Canada. Available online: https://menopausefoundationcanada.ca/pdf_files/Menopause_Work_Canada_2023EN.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Canadian Medical Association. Number of Active Physicians by Age, Gender and Province/Territory, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2019-11/2019-04-age-sex-prv.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Hauser, G.A.; Huber, I.C.; Keller, P.J.; Lauritzen, C.; Schneider, H.P. Evaluation of climacteric symptoms (Menopause Rating Scale). Zentralbl. Gynakol. 1994, 116, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, L.A.; DoMinh, T.; Strelow, F.; Gerbsch, S.; Schnitker, J.; Schneider, H.P.G. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) as outcome measure for hormone treatment? A validation study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariola, E.; Jack, G.; Pitts, M.; Riach, K.; Sarrel, P. Employment conditions and work-related stressors are associated with menopausal symptom reporting among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause 2017, 24, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanian, C.; Edgell, H.; Ardern, C.I.; Tamim, H. Hormone therapy use in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging: A cross-sectional analysis. Menopause 2018, 25, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Medical Association. Physician Workforce Survey, 2019, Q02. Satisfaction (Professional Life, Balance). 2019. Available online: https://surveys.cma.ca/link/survey89 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Beck, V.; Brewis, J.; Davies, A. The remains of the taboo: Experiences, attitudes, and knowledge about menopause in the workplace. Climacteric 2020, 23, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Current age | |

| ≤40 | 3 (1.4%) |

| 41–45 | 18 (8.3%) |

| 46–54 | 101 (46.5%) |

| 55–64 | 77 (35.5%) |

| ≥65 | 18 (8.3%) |

| Believe to be | |

| Postmenopausal | 156 (71.9%) |

| Perimenopausal | 61 (28.1%) |

| Age of last menstrual period | |

| Pre-menopausal | 61 (28.1%) |

| ≤40 | 13 (6.0%) |

| 41–45 | 14 (6.5%) |

| 46–54 | 103 (47.5%) |

| 55–64 | 26 (12.0%) |

| Location in Canada * | |

| Western | 93 (42.9%) |

| Central | 4 (1.8%) |

| Ontario region | 89 (41.0%) |

| Quebec region | 12 (5.5%) |

| Atlantic region | 19 (8.8%) |

| Practice Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Specialty Type | |

| Surgical | 65 (30.0%) |

| Non-surgical | 149 (68.7%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.4%) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–4 | 2 (0.9%) |

| 5–9 | 7 (3.2%) |

| 10–20 | 68 (31.3%) |

| >20 | 140 (64.5%) |

| Current work hours | |

| Part-time | 67 (30.9%) |

| Full-time | 150 (69.1%) |

| Type of practice | |

| Community | 98 (45.2%) |

| Academic | 56 (25.8%) |

| Both community and academic | 63 (29.0%) |

| Practice geographic setting | |

| Urban or peri-urban | 196 (90.3%) |

| Rural | 18 (8.3%) |

| Remote | 3 (1.4%) |

| Type of practice facility | |

| Hospital | 61 (28.1%) |

| Clinic | 70 (32.3%) |

| Both hospital and clinic | 86 (39.6) |

| Job structure | |

| Group practice member | 155 (71.4%) |

| Work independently | 62 (28.6%) |

| Flexible Work Hours | 136 (62.7%) |

| Night Shifts | 127 (58.5%) |

| Simple Linear Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 1.789 (0.160) | 1.483–2.113 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | 0.086 (0.009) | 0.068–0.104 | <0.001 |

| Model summary: F (1,204) = 86.90, p < 0.001, R2 = 29.9% | |||

| Multiple linear regression | |||

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 1.244 (0.340) | 0.573–1.916 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | 0.082 (0.009) | 0.064–0.101 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| ≤40 | −0.042 (0.582 | −1.190–1.106 | 0.943 |

| 41–45 | 0.349 (0.337) | −0.315–1.013 | 0.301 |

| 46–54 | 0.581 (0.260) | 0.069–1.093 | 0.026 |

| 55–64 | 0.157 (0.263) | −0.362–0.675 | 0.552 |

| ≥65 | Reference | ||

| Practice type | |||

| Community | 0.304 (0.168) | −0.026–0.635 | 0.071 |

| Academic | 0.344 (0.197) | −0.046–0.733 | 0.083 |

| Both community and academic | Reference | ||

| Practice facility | |||

| Hospital | −0.162 (0.179) | −0.515–0.190 | 0.366 |

| Clinic | −0.066 (0.191) | −0.443–0.311 | 0.730 |

| Both hospital and clinic | Reference | ||

| Specialty | |||

| Non-surgical | 0.037 (0.156) | −0.271–0.345 | 0.814 |

| Surgical | Reference | ||

| Job includes overnight call/shifts | 0.061 (0.150) | −0.235–0.358 | 0.683 |

| Have flexible working hours | 0.036 (0.147) | −0.253–0.326 | 0.804 |

| Model summary: F (12,190) = 9.05, p < 0.001, R2 = 36.4% | |||

| Simple Linear Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 1.023 (0.159) | 0.709–1.336 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | 0.083 (0.009) | 0.065–0.101 | <0.001 |

| Model summary: F (1,190) = 81.11, p < 0.001, R2 = 29.9% | |||

| Multiple linear regression | |||

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 0.701 (0.340) | 0.030–1.373 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | 0.083 (0.010) | 0.065–0.102 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| ≤40 | 0.012 (0.574) | −1.120–1.144 | 0.983 |

| 41–45 | 0.425 (0.332) | −0.230–1.080 | 0.202 |

| 46–54 | 0.122 (0.258) | −0.387–0.632 | 0.637 |

| 55–64 | −0.050 (0.261) | −0.565–0.466 | 0.849 |

| ≥65 | Reference | ||

| Practice type | |||

| Community | 0.208 (0.169) | −0.125–0.540 | 0.219 |

| Academic | −0.128 (0.198) | −0.519–0.263 | 0.521 |

| Both community and academic | Reference | ||

| Practice facility | |||

| Hospital | 0.140 (0.182) | −0.220–0.500 | 0.444 |

| Clinic | −0.236 (0.193) | −0.616–0.145 | 0.223 |

| Both hospital and clinic | Reference | ||

| Specialty | |||

| Non-surgical | 0.004 (0.157) | −0.305–0.314 | 0.977 |

| Surgical | Reference | ||

| Job includes overnight call/shifts | 0.002 (0.152) | −0.299–0.302 | 0.991 |

| Have flexible working hours | 0.322 (0.149) | 0.027–0.617 | 0.032 |

| Model summary: F (12,176) = 8.14, p < 0.001, R2 = 35.7% | |||

| Simple Linear Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 5.367 (0.198) | 4.978–5.757 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | −0.032 (0.011) | −0.054–−0.009 | 0.006 |

| Model summary: F (1,214) = 7.84, p = 0.006, R2 = 3.5% | |||

| Multiple linear regression | |||

| Predictors | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

| Constant | 6.025 (0.415) | 5.206 to 6.844 | <0.001 |

| Composite MRS score | −0.024 (0.012) | −0.047 to −0.001 | 0.039 |

| Age | |||

| ≤40 | −1.068 (0.723) | −2.494–0.358 | 0.141 |

| 41–45 | −0.726 (0.386) | −1.484–0.035 | 0.061 |

| 46–54 | −0.914 (0.300) | −1.505–−0.322 | 0.003 |

| 55–64 | −0.609 (0.303) | −1.208–−0.011 | 0.046 |

| ≥65 | Reference | ||

| Practice type | |||

| Community | −0.056 (0.209) | −0.469–0.357 | 0.789 |

| Academic | 0.109 (0.242) | −0.369–0.587 | 0.655 |

| Both community and academic | Reference | ||

| Practice facility | |||

| Hospital | 0.344 (0.219) | −0.088–0.776 | 0.118 |

| Clinic | −0.153 (0.237) | −0.620–0.314 | 0.519 |

| Both hospital and clinic | Reference | ||

| Specialty | |||

| Non-surgical | −0.209 (0.192) | -0.588–0.171 | 0.280 |

| Surgical | Reference | ||

| Job includes overnight call/shifts | −0.161 (0.186) | −0.528–0.206 | 0.388 |

| Have flexible working hours | 0.205 (0.181) | −0.152–0.562 | 0.260 |

| Model summary: F (12,200) = 2.54, p = 0.004, R2 = 13.2% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brent, S.E.; Shirreff, L.; Yanchar, N.L.; Christakis, M. Workplace Impact of Menopause Symptoms Among Canadian Women Physicians. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212699

Brent SE, Shirreff L, Yanchar NL, Christakis M. Workplace Impact of Menopause Symptoms Among Canadian Women Physicians. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212699

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrent, Shannon E., Lindsay Shirreff, Natalie L. Yanchar, and Marie Christakis. 2025. "Workplace Impact of Menopause Symptoms Among Canadian Women Physicians" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212699

APA StyleBrent, S. E., Shirreff, L., Yanchar, N. L., & Christakis, M. (2025). Workplace Impact of Menopause Symptoms Among Canadian Women Physicians. Healthcare, 13(21), 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212699