Evaluating Cardiovascular Patient Support Groups: A Cross-Sectional Control-Group Questionnaire Study of Patients and Healthcare Providers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Objectives

2.2. Participants and Criteria for Inclusion

- PSG members (individuals in the AHA);

- Control group (CVD patients not in the AHA);

- Healthcare providers (unrelated professionals in targeted fields).

2.3. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.4. Instruments

- Demographics: age, gender, marital status, nationality, and education level.

- Health literacy: Multiple-choice questions on CVD knowledge and a self-rated score of CVD knowledge (range 1 to 10). This section was developed by the authors drawing on their clinical and academic expertise in cardiovascular health. Items were refined through cognitive debriefing within a multidisciplinary team of healthcare experts and pilot-tested within a small sample of participants (n = 15) representing all three target groups, to ensure clarity, comprehensibility and content validity. The instrument has not yet undergone formal psychometric validation and should therefore be regarded as a pragmatic, context-specific tool.

- Personal health status: Self-reported diagnoses, recent doctor visits, medications, blood pressure measurements, weight, height, and blood sugar and blood lipid levels.

- HRQoL: assessment via the EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L [20].

- Perception of the PSG program (PSG members only): This section was intended to be exploratory in nature and aimed to provide a preliminary understanding of the perceived benefits of PSG participation. The Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) tool [21], which contains seven constructs (affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, self-efficacy), was used after forward and backward translation into German and validated via cognitive debriefing, and with permission of the authors [19].

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Health Literacy

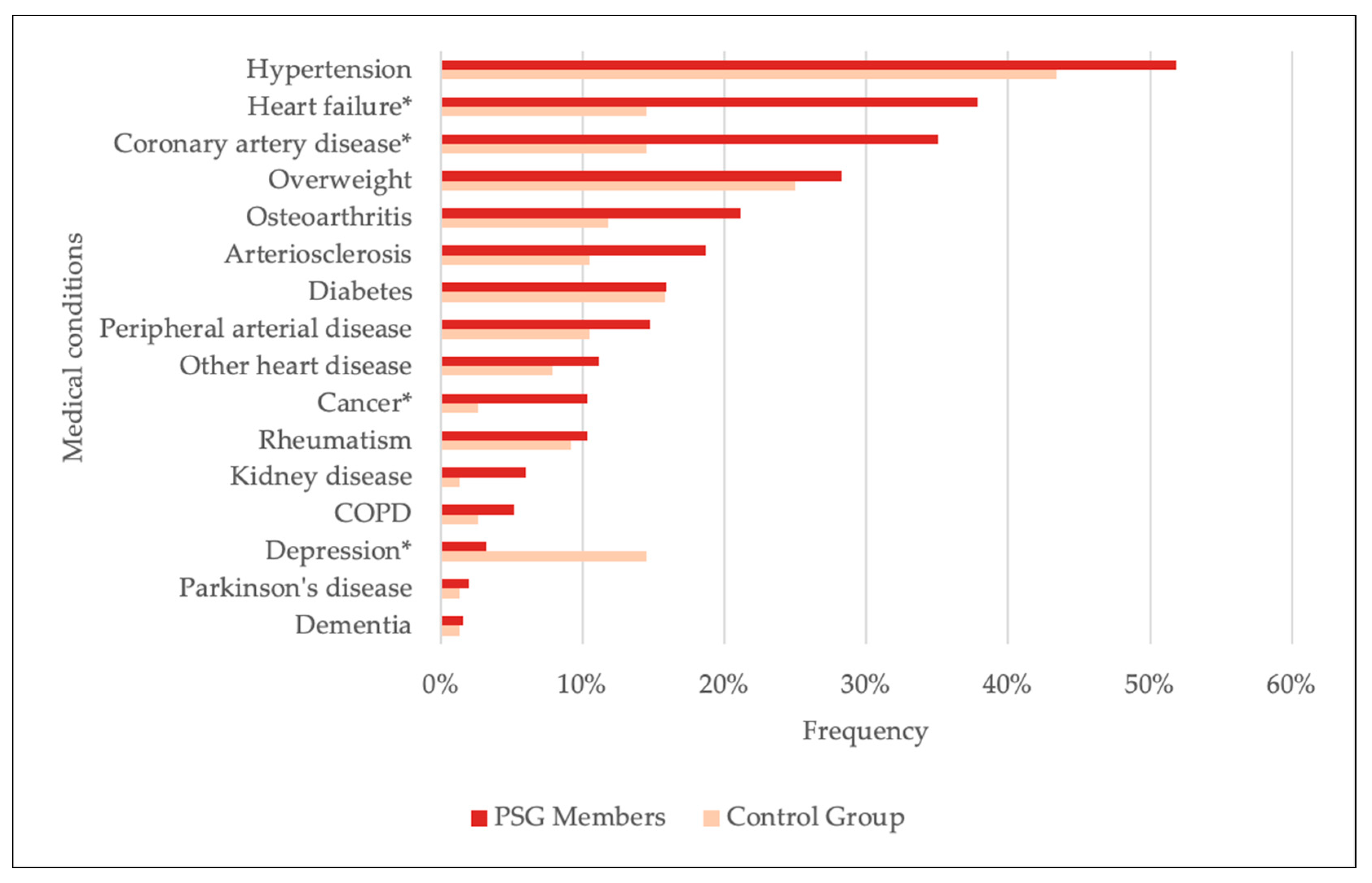

3.2. Self-Reported Health Data

3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

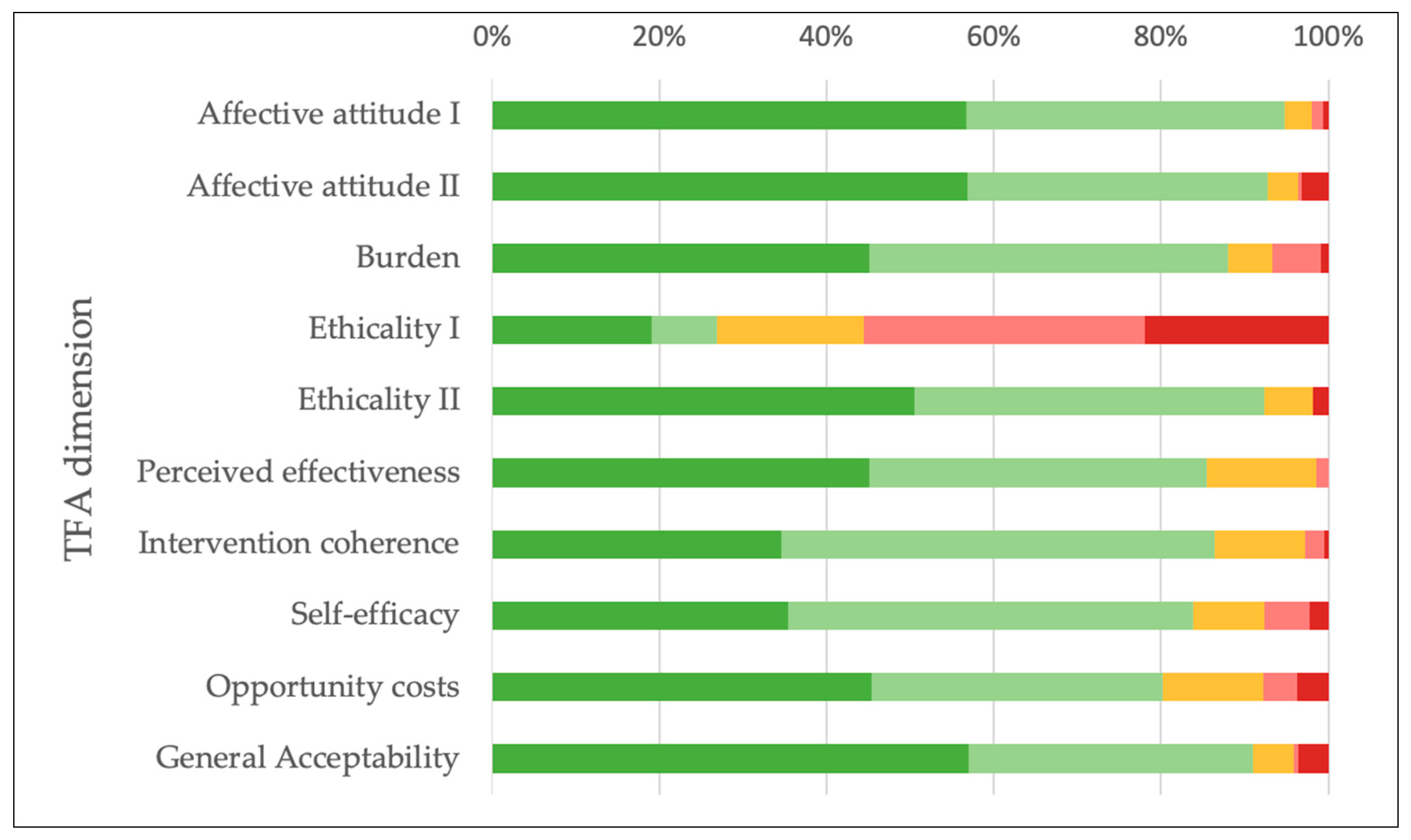

3.4. Perception of the Program

3.4.1. PSG Members

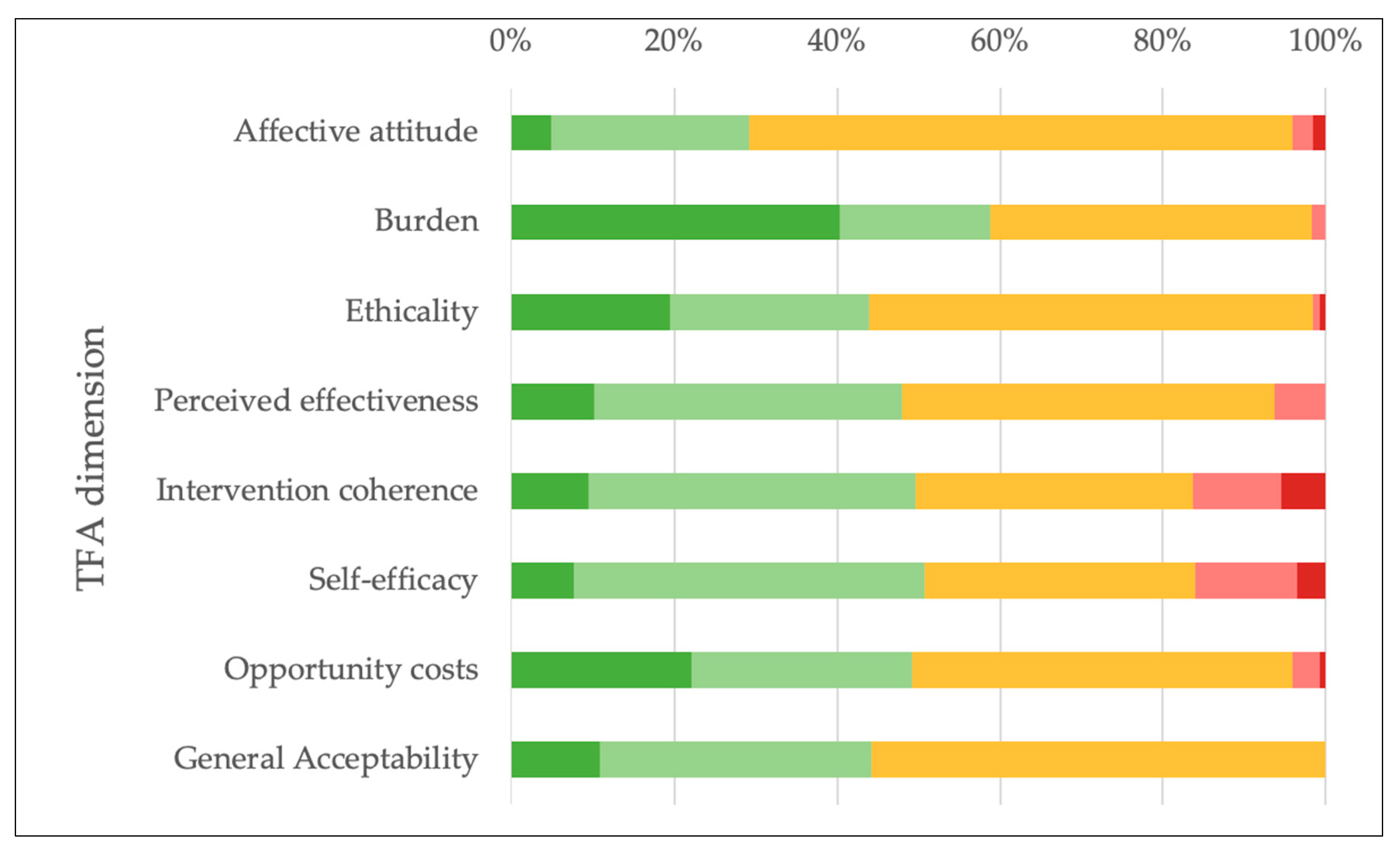

3.4.2. Healthcare Providers

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHA | Austrian Heart Association (Österreichischer Herzverband) |

| CR | Cardiac rehabilitation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| PSG | Patient support group |

| TFA | Theoretical Framework of Acceptability |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Participant Characteristics

| Healthcare Profession | Frequency (n) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| General Practitioner | 75 | 33.9 |

| Registered Nurse | 50 | 22.6 |

| Occupational therapist | 3 | 1.4 |

| Surgical Specialist | 1 | 0.5 |

| Specialist for Internal Medicine | 17 | 7.7 |

| Physiotherapist | 18 | 8.1 |

| Medical student | 27 | 12.2 |

| Other | 30 | 13.6 |

| Total | 221 | 100 |

Appendix A.2. Health Literacy

| Parameter | Answer Categories | PSG Members (%, n = 235) | Control Group (%, n = 60) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived informedness about own illness ‡ | I feel very well informed | 40.0 | 26.7 | <0.001 (χ2(3) = 23.339) * |

| I feel well informed | 53.2 | 46.7 | ||

| I feel moderately informed | 6.8 | 23.3 | ||

| I don’t feel very well informed | 0.0 | 3.3 | ||

| I don’t feel well informed at all | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Question Category | Correct Answer | PSG Members (%, n = 251) | Control Group (%, n = 76) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors for CVD | Vitamin deficiency (“no”) | 94.8 | 92.1 | 0.403 † |

| High blood pressure (“yes”) | 94.0 | 86.8 | 0.039 (χ2(1) = 4.261) * | |

| Being overweight (“yes”) | 85.7 | 88.2 | 0.579 (χ2(1) = 0.307) | |

| Smoking (“yes”) | 84.5 | 92.1 | 0.090 (χ2(1) = 2.872) | |

| Lack of exercise (“yes”) | 79.3 | 86.8 | 0.141 (χ2(1) = 2.169) | |

| High blood lipid levels (“yes”) | 79.3 | 80.3 | 0.853 (χ2(1) = 0.034) | |

| Stress (“yes”) | 72.9 | 76.3 | 0.554 (χ2(1) = 0.349) | |

| Diabetes (“yes”) | 51.4 | 56.6 | 0.428 (χ2(1) = 0.629) | |

| Poor dietary habits (“yes”) | 50.2 | 64.5 | 0.029 (χ2(1) = 4.778) * | |

| Sleep disorders (“yes”) | 20.3 | 32.9 | 0.023 (χ2(1) = 5.172) * | |

| Signs of a heart attack | Fever (“no”) | 98.0 | 100.0 | 0.594 † |

| Tightness/pressure on the chest (“yes”) | 82.5 | 86.8 | 0.368 (χ2(1) = 0.809) | |

| Chest pain (“yes”) | 76.1 | 75.0 | 0.845 (χ2(1) = 0.038) | |

| Pain in the left arm (“yes”) | 70.9 | 71.1 | 0.982 (χ2(1) = 0.001) | |

| Anxiety/feelings of apprehension/fear of dying (“yes”) | 62.2 | 47.4 | 0.022 (χ2(1) = 5.259) * | |

| Shortness of breath (“yes”) | 57.0 | 57.9 | 0.887 (χ2(1) = 0.020) | |

| Cold sweats (“yes”) | 46.2 | 43.4 | 0.668 (χ2(1) = 0.184) | |

| Palpitations (“yes”) | 44.2 | 44.7 | 0.937 (χ2(1) = 0.006) | |

| Nausea/vomiting (“yes”) | 30.3 | 26.3 | 0.506 (χ2(1) = 0.442) | |

| Upper abdominal pain (“yes”) | 21.5 | 28.9 | 0.179 (χ2(1) = 1.807) | |

| Pain in the neck/jaw area (“yes”) | 20.7 | 13.2 | 0.141 (χ2(1) = 2.169) | |

| Dizziness (“yes”) | 15.9 | 30.3 | 0.006 (χ2(1) = 7.698) * | |

| Signs of a stroke | Drooping mouth corner (“yes”) | 86.9 | 86.8 | 0.998 (χ2(1) = 0.000) |

| Speech disorder (“yes”) | 84.5 | 92.1 | 0.090 (χ2(1) = 2.872) | |

| One-sided arm paralysis (“yes”) | 72.5 | 76.3 | 0.511 (χ2(1) = 0.433) | |

| One-sided facial paralysis (“yes”) | 70.1 | 75.0 | 0.410 (χ2(1) = 0.678) | |

| One-sided sensory disturbance (“yes”) | 57.8 | 65.8 | 0.212 (χ2(1) = 1.559) | |

| Sudden one-sided vision disturbances (“yes”) | 49.8 | 48.7 | 0.865 (χ2(1) = 0.029) | |

| Balance disorder (“yes”) | 39.4 | 48.7 | 0.152 (χ2(1) = 2.051) | |

| Sudden severe headache (“yes”) | 34.7 | 38.2 | 0.577 (χ2(1) = 0.312) | |

| Dizziness (“yes”) | 25.9 | 32.9 | 0.231 (χ2(1) = 1.432) |

Appendix A.3. Self-Reported Health Data

| Parameter | Answer Categories | PSG Members (%, n = 249) | Control Group (%, n = 70) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | 52.2 | 47.1 | 0.454 (χ2(1) = 0.561) | |

| Self-reported medical conditions ‡ | Heart failure | 38.2 | 15.7 | <0.001 (χ2(1) = 12.399) |

| Coronary artery disease | 35.3 | 15.7 | 0.002 (χ2(1) = 9.834) | |

| Overweight | 28.5 | 27.1 | 0.822 (χ2(1) = 0.051) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 21.3 | 12.9 | 0.115 (χ2(1) = 2.479) | |

| Arteriosclerosis | 18.9 | 11.4 | 0.145 (χ2(1) = 2.124) | |

| Diabetes | 16.1 | 17.1 | 0.829 (χ2(1) = 0.047) | |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 14.9 | 11.4 | 0.466 (χ2(1) = 0.531) | |

| Other heart diseases | 11.2 | 8.6 | 0.522 (χ2(1) = 0.410) | |

| Cancer | 10.4 | 2.9 | 0.048 (χ2(1) = 3.926) | |

| Rheumatism | 10.4 | 10.0 | 0.915 (χ2(1) = 0.011) | |

| Kidney disease | 6.0 | 1.4 | 0.210 † | |

| COPD | 5.2 | 2.9 | 0.536 † | |

| Depression | 3.2 | 15.7 | <0.001 † | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1 † | |

| Dementia | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1 † |

| Parameter | Categories | PSG Members (%, n = 249) | Control Group (%, n = 70) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of self-reported medical conditions | 0–2 | 48.2 | 68.6 | 0.015 † |

| 3–6 | 49.0 | 30.0 | ||

| 7–10 | 2.0 | 1.4 | ||

| >10 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| Parameter | Statistic | PSG Members (n = 168) | Control Group (n = 42) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of cardiovascular disease (years) | Median | 12.0 | 5.0 | 0.001 (U = 2264.00) |

| IQR | 15 | 7 | ||

| Mean | 15.05 | 9.39 | ||

| SD | 11.65 | 9.74 |

| Parameter | Statistic | PSG Members (%, n = 163) | Control Group (%, n = 44) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of medications taken regularly | Median | 3.00 | 2.00 | p = 0.008 (U = 2663.50) |

| IQR | 3.0 | 3.8 | ||

| Mean | 3.70 | 2.80 | ||

| SD | 2.29 | 2.26 |

| Parameter | PSG Members (%, n = 251) | Control Group (%, n = 76) | p-Value (Test Statistic) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (weight and height provided) | 92.0 | 84.2 | 0.044 (χ2(1) = 4.042) | |

| Blood Pressure (systolic and diastolic values provided) | 57.4 | 57.9 | 0.935 (χ2(1) = 4.042) | |

| Blood Sugar Levels | FBS | 29.9 | 28.9 | 0.876 (χ2(1) = 0.024) |

| HbA1c | 21.1 | 17.1 | 0.445 (χ2(1) = 0.582) | |

| Blood Lipid Levels | TC | 30.7 | 21.1 | 0.103 (χ2(1) = 2.655) |

| LDL-C | 28.3 | 18.4 | 0.086 (χ2(1) = 2.952) | |

| TG | 27.1 | 21.1 | 0.291 (χ2(1) = 1.114) | |

Appendix A.4. Health-Related Quality of Life

| Parameter | Statistic | PSG Members (n = 226) | Control Group (n = 64) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related Quality of Life (EQ-5D-5L index) | Median | 0.943 | 0.913 | 0.251 (U = 6562.00) |

| IQR | 0.120 | 0.173 | ||

| Mean | 0.912 | 0.875 | ||

| SD | 0.101 | 0.153 |

| Domain | Response Options | PSG Members (%) | Control Group (%) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | n = 241 | n = 65 | ||

| I have no problems walking around | 75.5 | 69.2 | 0.130 † | |

| I have slight problems walking around | 17.8 | 16.9 | ||

| I have moderate problems walking around | 5.8 | 9.2 | ||

| I have severe problems walking around | 0.8 | 4.6 | ||

| I am unable to walk around | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Independence | n = 240 | n = 67 | ||

| I have no problems washing myself or getting dressed | 93.8 | 94.0 | 0.907 † | |

| I have slight problems washing myself or getting dressed | 4.6 | 6.0 | ||

| I have moderate problems washing myself or getting dressed | 1.3 | 0.0 | ||

| I have great difficulty washing or dressing myself | 0.4 | 0.0 | ||

| I am unable to wash or dress myself | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Daily Activities | n = 240 | n = 67 | ||

| I have no problems performing my daily activities | 82.1 | 80.6 | 0.316 † | |

| I have slight problems performing my daily activities | 14.2 | 11.9 | ||

| I have moderate problems performing my daily activities | 2.9 | 4.5 | ||

| I have great problems performing my daily activities | 0.0 | 1.5 | ||

| I am unable to perform my daily activities | 0.8 | 1.5 | ||

| Pain/Physical discomfort | n = 233 | n = 67 | ||

| I have no pain or discomfort. | 36.9 | 43.3 | 0.512 (χ2(3) = 2.303) | |

| I have mild pain or discomfort. | 39.9 | 29.9 | ||

| I have moderate pain or discomfort. | 21.0 | 23.9 | ||

| I have severe pain or discomfort. | 2.1 | 3.0 | ||

| I have extreme pain or discomfort. | 0.0 | 0 | ||

| Anxiety/Depression | n = 235 | n = 66 | ||

| I am not anxious or depressed. | 68.9 | 48.5 | <0.001 (χ2(3) = 18.077) | |

| I am a little anxious or depressed. | 24.3 | 30.3 | ||

| I am moderately anxious or depressed. | 6.0 | 13.6 | ||

| I am very anxious or depressed. | 0.9 | 7.6 | ||

| I am extremely anxious or depressed. | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Parameter | Statistic | PSG Members (n = 235) | Control Group (n = 63) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D Visual Analog Scale Health Score (0–100) | Median | 80.00 | 75.00 | 0.484 (U = 6982.50) |

| IQR | 25 | 38 | ||

| Mean | 72.6 | 70.5 | ||

| SD | ±17.7 | ±19.7 |

Appendix A.5. Perception of the Program

| Domain | Response Options | n (Responses) | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude I “Do you like or dislike the program of the AHA?” | Strongly dislike | 1 | 0.6 |

| Dislike | 2 | 1.3 | |

| No opinion | 5 | 3.2 | |

| Like | 59 | 38.1 | |

| Strongly like | 88 | 56.8 | |

| Total | 155 | 100 | |

| Affective attitude II “How comfortable do you feel participating in the activities of the AHA?” | Very uncomfortable | 7 | 3.2 |

| Uncomfortable | 1 | 0.5 | |

| No opinion | 8 | 3.6 | |

| Comfortable | 79 | 35.9 | |

| Very comfortable | 125 | 56.8 | |

| Total | 220 | 100 | |

| Burden “How much effort does it take you to participate in the activities of the AHA?” | No effort at all | 102 | 45.1 |

| A little effort | 97 | 42.9 | |

| No opinion | 12 | 5.3 | |

| A lot of effort | 13 | 5.8 | |

| Huge effort | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Total | 226 | 100 | |

| Ethicality I “There are moral or ethical consequences to participating in the activities of the AHA.” | Strongly disagree | 39 | 19.0 |

| Disagree | 16 | 7.8 | |

| No opinion | 36 | 17.6 | |

| Agree | 69 | 33.7 | |

| Strongly agree | 45 | 22.0 | |

| Total | 205 | 100 | |

| Ethicality II “How fair is the program of the AHA for people with cardiovascular diseases?” | Very unfair | 4 | 1.8 |

| Unfair | 0 | 0.0 | |

| No opinion | 13 | 5.9 | |

| Fair | 93 | 41.9 | |

| Very Fair | 112 | 50.5 | |

| Total | 222 | 100 | |

| Perceived effectiveness “Participating in the activities of the AHA has strengthened me in managing my cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 0 | 0.0 |

| Disagree | 3 | 1.4 | |

| No opinion | 28 | 13.1 | |

| Agree | 86 | 40.4 | |

| Strongly agree | 96 | 45.1 | |

| Total | 213 | 100 | |

| Intervention coherence “It is clear to me how participating in the activities of the AHA will help me manage my cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 1 | 0.5 |

| Disagree | 5 | 2.3 | |

| No opinion | 23 | 10.7 | |

| Agree | 111 | 51.9 | |

| Strongly agree | 74 | 34.6 | |

| Total | 214 | 100 | |

| Self-efficacy “How confident do you feel about your ability to participate in the activities of the AHA?” | Very unconfident | 5 | 2.2 |

| Unconfident | 12 | 5.4 | |

| No opinion | 19 | 8.5 | |

| Confident | 108 | 48.4 | |

| Very confident | 79 | 35.4 | |

| Total | 223 | 100 | |

| Opportunity costs “Participating in the activities of the AHA interferes with my other priorities.” | Strongly disagree | 99 | 45.4 |

| Disagree | 76 | 34.9 | |

| No opinion | 26 | 11.9 | |

| Agree | 9 | 4.1 | |

| Strongly agree | 8 | 3.7 | |

| Total | 218 | 100 | |

| General Acceptability “How acceptable is the program of the AHA to you?” | Completely unacceptable | 8 | 3.6 |

| Unacceptable | 1 | 0.5 | |

| No opinion | 11 | 5.0 | |

| Acceptable | 75 | 33.9 | |

| Completely acceptable | 126 | 57.0 | |

| Total | 221 | 100 |

| Statement | Responses Options | n (Responses) | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participating in the activities of the Heart Association strengthens me in my ability to deal with my own illness. | Yes | 129 | 52.2 |

| No | 118 | 47.8 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 | |

| The Heart Association constitutes an important social network for me and gives me strength in living with the illness. | Yes | 129 | 52.2 |

| No | 118 | 47.8 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 | |

| The Heart Association provides me with support that I do not receive from any doctor or other healthcare provider. | Yes | 56 | 22.7 |

| No | 191 | 77.3 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 | |

| The Heart Association is an important source of trustworthy medical information. | Yes | 119 | 48.2 |

| No | 128 | 51.8 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 | |

| Membership in the Heart Association helps me navigate the healthcare system. | Yes | 80 | 32.4 |

| No | 167 | 67.6 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 | |

| Participating in the activities of the Heart Association improves my quality of life. | Yes | 172 | 69.6 |

| No | 75 | 30.4 | |

| Total | 247 | 100 |

| Domain | Response Options | n (Responses) | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude “Do you like or dislike the activities of the AHA?” | Strongly dislike | 2 | 1.6 |

| Dislike | 3 | 2.4 | |

| No opinion | 82 | 66.7 | |

| Like | 30 | 24.4 | |

| Strongly like | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Total | 123 | 100 | |

| Burden “How much effort does it take you to collaborate with the AHA?” | No effort at all | 46 | 40.4 |

| A little effort | 21 | 18.4 | |

| No opinion | 45 | 39.5 | |

| A lot of effort | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Huge effort | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 114 | 100 | |

| Ethicality “There are moral or ethical consequences to participating in the activities of the AHA.” | Strongly disagree | 24 | 19.5 |

| Disagree | 30 | 24.4 | |

| No opinion | 67 | 54.5 | |

| Agree | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Strongly agree | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 123 | 100 | |

| Perceived effectiveness “Participating in the activities of the AHA has strengthened its members in managing their cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 0 | 0.0 |

| Disagree | 8 | 6.3 | |

| No opinion | 58 | 45.7 | |

| Agree | 48 | 37.8 | |

| Strongly agree | 13 | 10.2 | |

| Total | 127 | 100 | |

| Intervention coherence “It is clear to me how participating in the activities of the AHA will help patients with cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 8 | 5.4 |

| Disagree | 16 | 10.9 | |

| No opinion | 50 | 34.0 | |

| Agree | 59 | 40.1 | |

| Strongly agree | 14 | 9.5 | |

| Total | 147 | 100 | |

| Self-efficacy “How confident do you feel about patients’ ability to participate in the activities of the AHA?” | Very unconfident | 5 | 3.5 |

| Unconfident | 18 | 12.5 | |

| No opinion | 48 | 33.3 | |

| Confident | 62 | 43.1 | |

| Very confident | 11 | 7.6 | |

| Total | 144 | 100 | |

| Opportunity costs “Collaborating with the AHA interferes with my other priorities.” | Strongly disagree | 27 | 22.1 |

| Disagree | 33 | 27.0 | |

| No opinion | 57 | 46.7 | |

| Agree | 4 | 3.3 | |

| Strongly agree | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 122 | 100 | |

| General Acceptability “How acceptable is the program of the AHA to you?” | completely unacceptable | 0 | 0.0 |

| unacceptable | 0 | 0.0 | |

| no opinion | 67 | 55.8 | |

| acceptable | 40 | 33.3 | |

| completely acceptable | 13 | 10.8 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 |

Appendix B

Sensitivity Analysis

| Domain | Response Options | n (Responses) | % of Respondents | Δ % * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude “Do you like or dislike the activities of the AHA?” | Strongly dislike | 1 | 0.9 | −0.7 |

| Dislike | 3 | 2.8 | +0.4 | |

| No opinion | 73 | 67.6 | +0.9 | |

| Like | 26 | 24.1 | −0.3 | |

| Strongly like | 5 | 4.6 | −0.3 | |

| Total | 108 | 100 | n/a | |

| Burden “How much effort does it take you to collaborate with the AHA?” | No effort at all | 41 | 41.0 | +0.6 |

| A little effort | 19 | 19.0 | +0.6 | |

| No opinion | 38 | 38.0 | −1.5 | |

| A lot of effort | 2 | 2.0 | +0.2 | |

| Huge effort | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 | n/a | |

| Ethicality “There are moral or ethical consequences to participating in the activities of the AHA.” | Strongly disagree | 23 | 21.3 | +1.8 |

| Disagree | 24 | 22.2 | −2.2 | |

| No opinion | 60 | 55.6 | +1.1 | |

| Agree | 1 | 0.9 | +0.1 | |

| Strongly agree | 0 | 0.0 | +0.8 | |

| Total | 108 | 100 | n/a | |

| Perceived effectiveness “Participating in the activities of the AHA has strengthened its members in managing their cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 7 | 6.2 | −0.1 | |

| No opinion | 52 | 46.0 | +0.3 | |

| Agree | 42 | 37.2 | −0.6 | |

| Strongly agree | 12 | 10.6 | +0.4 | |

| Total | 113 | 100 | n/a | |

| Intervention coherence “It is clear to me how participating in the activitites of the AHA will help patients with cardiovascular disease.” | Strongly disagree | 6 | 4.7 | −0.7 |

| Disagree | 13 | 10.1 | −0.7 | |

| No opinion | 44 | 34.4 | +0.4 | |

| Agree | 52 | 39.8 | −0.3 | |

| Strongly agree | 14 | 10.9 | +1.4 | |

| Total | 129 | 100 | n/a | |

| Self-efficacy “How confident do you feel about patients’ ability to participate in the activities of the AHA?” | Very unconfident | 4 | 3.1 | −0.4 |

| Unconfident | 15 | 11.8 | −0.7 | |

| No opinion | 43 | 33.9 | +0.6 | |

| Confident | 57 | 44.1 | +1.0 | |

| Very confident | 9 | 7.1 | −0.5 | |

| Total | 128 | 100 | n/a | |

| Opportunity costs “Collaborating with the AHA interferes with my other priorities.” | Strongly disagree | 27 | 25.0 | +2.9 |

| Disagree | 28 | 25.9 | −1.1 | |

| No opinion | 49 | 45.4 | −1.3 | |

| Agree | 3 | 2.8 | −0.5 | |

| Strongly agree | 1 | 0.9 | +0.1 | |

| Total | 108 | 100 | n/a | |

| General Acceptability “How acceptable is the program of the AHA to you?” | completely unacceptable | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| unacceptable | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| no opinion | 58 | 55.8 | 0 | |

| acceptable | 35 | 32.7 | −0.6 | |

| completely acceptable | 12 | 11.5 | +0.7 | |

| Total | 105 | 100 | n/a |

References

- Benziger, C.P.; Roth, G.A.; Moran, A.E. The Global Burden of Disease Study and the Preventable Burden of NCD. Glob. Heart 2016, 11, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebler, R.; Winkler, P.; Delcour, J.; Eisenmann, A. Herz-Kreislauf-Erkrankungen in Österreich. Update 2020. Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz, Wien, 2021. Available online: https://jasmin.goeg.at/id/eprint/1906/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Bansilal, S.; Castellano, J.M.; Fuster, V. Global burden of CVD: Focus on secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 201, S1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Joshi, A. An Overview of Chronic Disease Models: A Systematic Literature Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 7, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, M.C.S.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Yam, C.; Poon, C.M.; Chung, R.Y.; Chong, M.; Fang, Y.; Wang, H.H.X.; Liang, M.; et al. Benefits and limitations of implementing Chronic Care Model (CCM) in primary care programs: A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 258, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.; Fernandes, A.; Cruzeiro, S.; Jesus, R.; Araújo, N.; Araújo, I. Cardiac rehabilitation program and health literacy levels: A cross-sectional, descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederichs, C.; Jordan, S.; Domanska, O.; Neuhauser, H. Health literacy in men and women with cardiovascular diseases and its association with the use of health care services—Results from the population-based GEDA2014/2015-EHIS survey in Germany. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschaftary, A.; Hess, N.; Hiltner, S.; Oertelt-Prigione, S. The association between sex, age and health literacy and the uptake of cardiovascular prevention: A cross-sectional analysis in a primary care setting. J. Public Health 2018, 26, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanejima, Y.; Shimogai, T.; Kitamura, M.; Ishihara, K.; Izawa, K.P. Impact of health literacy in patients with cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, A.; Talevski, J.; Niebauer, J.; Gutenberg, J.; Kefalianos, E.; Mayr, B.; Sareban, M.; Kulnik, S.T. Health literacy interventions for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease: A scoping review. Open Heart 2022, 9, e001895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, P.; Grimsmo, J.; Nilsson, B.B.; Bye, A.; Finbråten, H.S. Health literacy in patients participating in cardiac rehabilitation: A prospective cohort study with pre-post-test design. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2024, 22, 200314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibben, G.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cotie, L.M.; Vanzella, L.M.; Pakosh, M.; Ghisi, G.L.M. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines and Consensus Statements for Cardiac Rehabilitation Delivery: Consensus, Divergence, and Important Knowledge Gaps. Can. J. Cardiol. 2024, 40, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabboul, N.N.; Tomlinson, G.; Francis, T.A.; Grace, S.L.; Chaves, G.; Rac, V.; Daou-Kabboul, T.; Bielecki, J.M.; Alter, D.A.; Krahn, M. Comparative Effectiveness of the Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Mortality and Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.M.; Booth, L.; Moore, D.; Mathers, J. Peer support for people with chronic conditions: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-J.; Chen, C.-H.; Tsai, S.-F. Effects of patient support group on health literacy: A study using the Multidimensional Health Literacy Questionnaire. Medicine 2023, 102, e33901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Manzari, Z.S.; Mohammadpourhodki, R. Peer-support interventions and related outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastnak, W. Long-term cardiac rehabilitation and cardioprotective changes in lifestyle. Br. J. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aqeel, S.A.; AlAujan, S.S.; Almazrou, S.H. The Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iPCQ) and the Medical Consumption Questionnaire (iMCQ): Translation and Cognitive Debriefing of the Arabic Version. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Development of a theory-informed questionnaire to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.; Graf von der Schulenburg, J.-M.; Greiner, W. German Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L. PharmacoEconomics 2018, 36, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Hu, X. Peer support interventions on quality of life, depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy among patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mase, R.; Halasyamani, L.; Choi, H.; Heisler, M. Who Signs Up for and Engages in a Peer Support Heart Failure Self-management Intervention. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, S35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Jia, R.; Zhou, X.; Lu, G.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, C. The effectiveness of peer support on self-efficacy and self-management in people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, D.; Benson, G.; Campbell, S.; Sillah, A.; Berra, K. Measures of Patient Activation and Social Support in a Peer-Led Support Network for Women With Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2016, 36, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majjouti, K.; Küppers, L.; Thielmann, A.; Redaélli, M.; Vitinius, F.; Funke, C.; van der Arend, I.; Pilic, L.; Hessbrügge, M.; Stock, S.; et al. Family doctors’ attitudes toward peer support programs for type 2 diabetes and/or coronary artery disease: An exploratory survey among German practitioners. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, R.; Jones, M.; Pietilä, I.; Harju, E. Perspectives of oncology nurses on peer support for patients with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 51, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, E.; Nickel, S.; Trojan, A.; Klein, J.; Kofahl, C. Self-help friendliness in cancer care: A cross-sectional study among self-help group leaders in Germany. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 3005–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, M.; Hyde, M.K.; Occhipinti, S.; Youl, P.H.; Dunn, J.; Chambers, S.K. A prospective and population-based inquiry on the use and acceptability of peer support for women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | PSG Members (n = 251) | Control Group (n = 76) | p-Value (Test Statistic) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, median (IQR) | 74.00 (12) | 59.00 (23) | <0.001 (U = 2263.00) * | |

| Gender (%) | female | 59.0 | 48.7 | 0.007 † |

| male | 41.0 | 47.4 | ||

| no answer | 0.0 | 3.9 | ||

| Marital Status (%) | married/in a relationship | 59.4 | 72.4 | 0.024 † |

| divorced/widowed | 33.5 | 17.1 | ||

| single | 5.2 | 9.2 | ||

| no answer | 2.0 | 1.3 | ||

| Highest Level of Education (%) | primary school | 6.8 | 0.0 | <0.001 *† |

| lower secondary education | 12.7 | 9.2 | ||

| apprenticeship/vocational school | 50.6 | 44.7 | ||

| high school | 16.3 | 11.8 | ||

| university degree | 12.4 | 34.2 | ||

| no answer | 1.2 | 0.0 | ||

| Years Since Onset of CVD (%) | <5 years | 8.4 | 14.5 | 0.008 (χ2(5) = 14.911) |

| 5–10 years | 21.9 | 23.7 | ||

| 11–20 years | 17.9 | 5.3 | ||

| 21–30 years | 12.0 | 5.3 | ||

| >30 years | 5.2 | 2.6 | ||

| no answer | 34.7 | 48.7 | ||

| Parameter | Statistic | PSG Members (n = 229) | Control Group (n = 76) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported CVD knowledge score (0–10) ‡ | Median | 7.00 | 6.00 | 0.014 (U = 7088.00) * |

| IQR | 3 | 3 | ||

| Mean | 6.70 | 6.07 | ||

| SD | ±1.84 | ±1.98 |

| Parameter | Answer Categories | PSG Members (%, n = 251) | Control Group (%, n = 76) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main sources of medical information on CVD and healthy lifestyle ‡ | Austrian Heart Association | 76.9 | 11.8 | <0.001 (χ2(1) = 104.538) * |

| Specialist | 72.9 | 63.2 | 0.102 (χ2(1) = 2.674) | |

| General practitioner/family doctor | 53.8 | 52.6 | 0.860 (χ2(1) = 0.031) | |

| Internet | 17.5 | 32.9 | 0.004 (χ2(1) = 8.272) * | |

| Magazines | 17.1 | 14.5 | 0.585 (χ2(1) = 0.299) | |

| Television | 12.0 | 13.2 | 0.779 (χ2(1) = 0.079) | |

| Friends | 6.0 | 18.4 | <0.001 (χ2(1) = 11.179) * | |

| Acquaintances | 2.8 | 6.6 | 0.159 † | |

| Radio | 1.2 | 2.6 | 0.330 † | |

| Other | 1.6 | 11.8 | <0.001 *† |

| Parameter | Category | PSG Members (%) | Control Group (%) | p-Value (Test Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | n = 231 | n = 64 | 0.525 † | |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 1.3 | 0.0 | ||

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 35.5 | 39.1 | ||

| Pre-obesity (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 46.8 | 35.9 | ||

| Class I obesity (30–34.9 kg/m2) | 12.1 | 17.2 | ||

| Class II obesity (35–39.9 kg/m2) | 2.6 | 4.7 | ||

| Class III obesity (≥40 kg/m2) | 1.7 | 3.1 | ||

| Blood Pressure | n = 159 | n = 44 | 0.037 (χ2(3) = 8.463) | |

| Normal (<130/85 mmHg) | 43.4 | 36.4 | ||

| Normal–high (130–139/85–89 mmHg) | 28.3 | 29.5 | ||

| Grade I hypertension (140–159/90–99 mmHg) | 26.4 | 22.7 | ||

| Grade II hypertension (≥160/100 mmHg) | 1.9 | 11.4 | ||

| Blood Sugar Level | n = 79 | n = 23 | 0.577 (χ2(1) = 0.312) | |

| Normal (HbA1c < 6.5% or FBS < 100 mg/dL) | 45.6 | 52.2 | ||

| Elevated (HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or FBS ≥ 100 mg/dL) | 54.4 | 47.8 | ||

| Blood Lipid Level | n = 79 | n = 17 | 0.758 (χ2(1) = 0.214) | |

| Normal (TC < 200 mg/dL, LDL-C < 160 mg/dL, or TG < 150 mg/dL) | 75.9 | 70.6 | ||

| Elevated (TC ≥ 200 mg/dL, LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dL, or TG ≥ 150 mg/dL) | 24.1 | 29.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stefanovic, D.; Pantoglou, J.; Voggenberger, L.; Bekelaer, F.; Mader, M.; Zelko, E. Evaluating Cardiovascular Patient Support Groups: A Cross-Sectional Control-Group Questionnaire Study of Patients and Healthcare Providers. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212692

Stefanovic D, Pantoglou J, Voggenberger L, Bekelaer F, Mader M, Zelko E. Evaluating Cardiovascular Patient Support Groups: A Cross-Sectional Control-Group Questionnaire Study of Patients and Healthcare Providers. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212692

Chicago/Turabian StyleStefanovic, Dana, Julia Pantoglou, Lisa Voggenberger, Fabian Bekelaer, Markus Mader, and Erika Zelko. 2025. "Evaluating Cardiovascular Patient Support Groups: A Cross-Sectional Control-Group Questionnaire Study of Patients and Healthcare Providers" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212692

APA StyleStefanovic, D., Pantoglou, J., Voggenberger, L., Bekelaer, F., Mader, M., & Zelko, E. (2025). Evaluating Cardiovascular Patient Support Groups: A Cross-Sectional Control-Group Questionnaire Study of Patients and Healthcare Providers. Healthcare, 13(21), 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212692