Mpox-Related Stigma Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

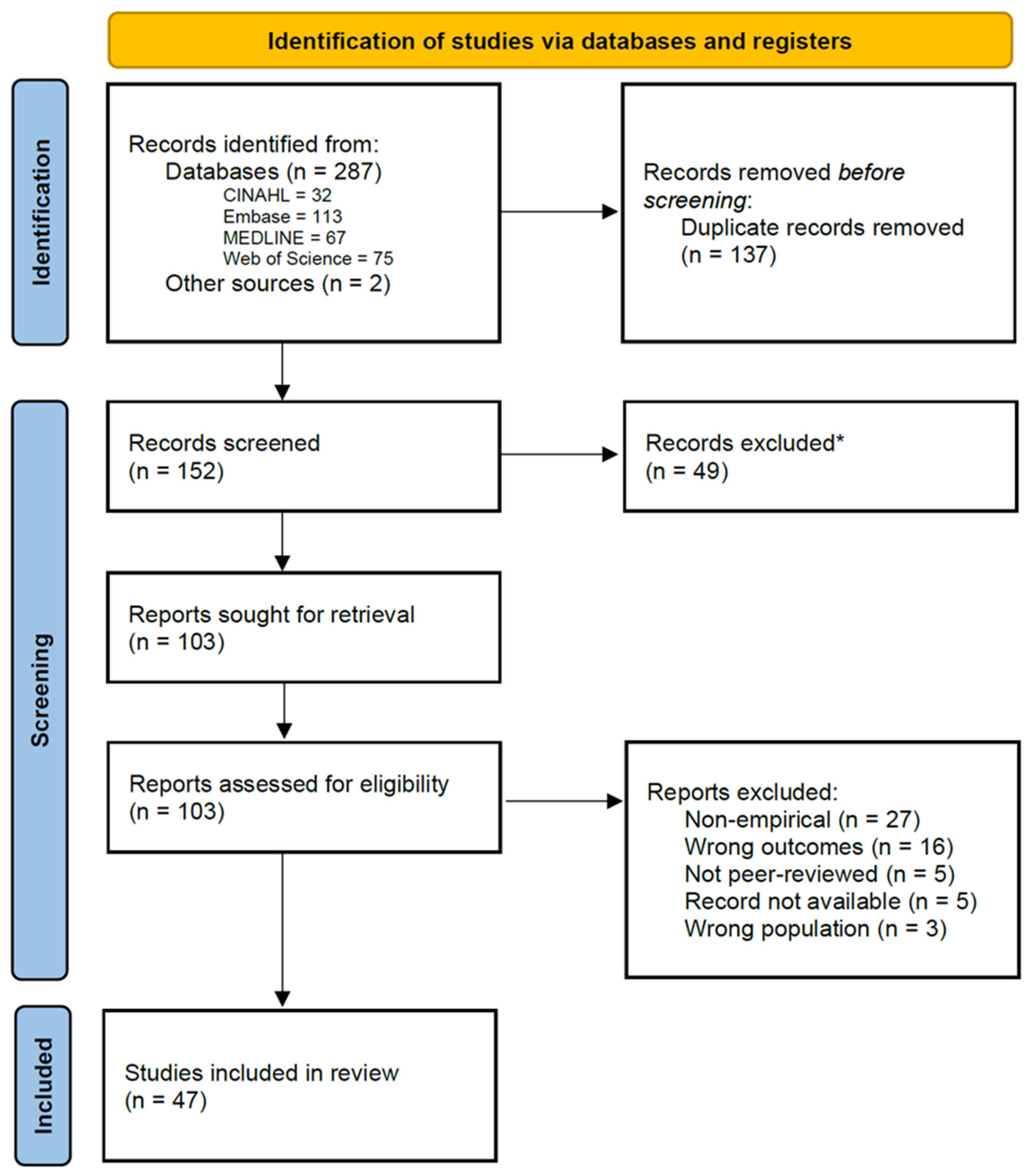

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Healthcare Experiences

3.2. Media Influence

3.3. Internalised and Anticipated Stigma

3.4. Public Health Messaging

3.5. Community Responses

3.6. Psychosocial Impact

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions and Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Director-General Declares Mpox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2024.

- Laurenson-Schafer, H.; Sklenovská, N.; Hoxha, A.; Kerr, S.M.; Ndumbi, P.; Fitzner, J.; Almiron, M.; De Sousa, L.A.; Briand, S.; Cenciarelli, O.; et al. Description of the first global outbreak of mpox: An analysis of global surveillance data. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1012–e1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A.; Singhal, R.; Pareek, A.; Chuturgoon, A.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Chattu, V.K. Global spread of clade Ib mpox: A growing concern. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessain, A.; Nakoune, E.; Yazdanpanah, Y. Monkeypox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curaudeau, M.; Besombes, C.; Nakouné, E.; Fontanet, A.; Gessain, A.; Hassanin, A. Identifying the Most Probable Mammal Reservoir Hosts for Monkeypox Virus Based on Ecological Niche Comparisons. Viruses 2023, 15, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, S.T.; Lehmann, M.C.; Treutlein, M.; Fiethe, A.; Kossow, A.; Küfer-Weiß, A.; Nießen, J.; Grüne, B. Mpox outbreak 2022: An overview of all cases reported to the Cologne Health Department. Infection 2023, 51, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Park, S.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, M.; Choi, Y.S.; Yeo, S.G.; Lee, J.; Koyanagi, A.; Jacob, L.; Smith, L.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with mpox during the 2022 mpox outbreak compared with those before the outbreak: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Epidemiological Summary Report: 2022–2023 Mpox Outbreak in Canada. 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/epidemiological-summary-report-2022-23-mpox-outbreak-canada.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- About Mpox; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025.

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chard, A.N.; Dalton, A.F.; Diallo, A.O.; Moulia, D.L.; Deputy, N.P.; Zecca, I.B.; Quilter, L.A.S.; Kachur, R.E.; McCollum, A.M.; Rowlands, J.V.; et al. Risk of Clade II Mpox Associated with Intimate and Nonintimate Close Contact Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Adults—United States, August 2022–July 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugwu, C.L.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Wu, J.; Kong, J.D.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Woldegerima, W.A. Risk factors associated with human Mpox infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicknall, I.H.; Pollock, E.D.; Clay, P.A.; Oster, A.M.; Charniga, K.; Masters, N.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Rainisch, G.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Gift, T.L. Modeling the Impact of Sexual Networks in the Transmission of Monkeypox virus Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Pittman, P.R. Mpox (Monkeypox) in Pregnancy: Viral Clade Differences and Their Associations with Varying Obstetrical and Fetal Outcomes. Viruses 2023, 15, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, A.M.; Haston, J.; McCormick, D.W.; Reynolds, M.; Chatham-Stephens, K.; McCollum, A.M.; Godfred-Cato, S. Mpox in Children and Adolescents: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pischel, L.; Martini, B.A.; Yu, N.; Cacesse, D.; Tracy, M.; Kharbanda, K.; Ahmed, N.; Patel, K.M.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Malik, A.A.; et al. Vaccine effectiveness of 3rd generation mpox vaccines against mpox and disease severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A.; Zucker, J.; Bell, E.; Flores, J.; Gordon, L.; Mitjà, O.; Suñer, C.; Lemaignen, A.; Jamard, S.; Nozza, S.; et al. Mpox in people with past infection or a complete vaccination course: A global case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallpox and Mpox Vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024.

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian Immunisation Handbook; Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Damaso, C.R. Phasing out monkeypox: Mpox is the new name for an old disease. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2023, 17, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Robinson, K.H.; Metcalf, A.; Ivory, K.; Mooney-Somers, J.; Race, K.; Skinner, S.R. Australians of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities. In Culture, Diversity and Health in Australia; Routledge/Taylor Francis: London, UK, 2021; pp. 213–231. ISBN 978-1-00-313855-6. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.; Aggleton, P.; Williams, M.; Kong, T.; Reddy, V.; Harrad, D.; Reis, T.; Parker, R. Men who have sex with men: Stigma and discrimination. Lancet 2012, 380, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminalisation of Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Acts; The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Berger, M.N.; Taba, M.; Marino, J.L.; Lim, M.S.C.; Skinner, S.R. Social Media Use and Health and Well-being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e38449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, S.G.; McAteer, J.; Jepson, R. Interactions Between Health Professionals and Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Patients in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. J. Homosex. 2023, 70, 250–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agroia, H.; Smith, E.; Vaidya, A.; Rudman, S.; Roy, M. Monkeypox (Mpox) Vaccine Hesitancy Among Mpox Cases: A Qualitative Study. Health Promot. Pract. 2025, 26, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, A.; McGee, K.; Farley, J.; Kwong, J.; McNabb, K.; Voss, J. Combating Stigma in the Era of Monkeypox-Is History Repeating Itself? J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesty, C.P.; Hemingway, C.; Woolgar, J.; Taylor, K.; Lawton, M.D.; Waheed, M.W.; Holford, D.; Taegtmeyer, M. Community led health promotion to counter stigma and increase trust amongst priority populations: Lessons from the 2022–2023 UK mpox outbreak. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulcão, C.d.S.; Oliveira Miranda, L.d.S.; Joaquim, J.d.S.; de Oliveira Carvalho, K.M.; Evangelista Sant’Ana, R.S.; Machuca-Contreras, F.; dos Santos Silva, G.W.; Araujo, J.S.; Guimarães de Almeida, L.C.; de Sousa, A.R. Vulnerabilidades de Homens Gays e Bissexuais à Mpox no brasil: Implicações Clínico-Sociais Para Enfermagem. Enferm. Foco 2024, 15, S120–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulcão, C.d.S.; Prates, P.E.G.; Pedrosa, I.M.B.; de Santana Santos, G.R.; de Oliveira, L.B.; de Souza Joaquim, J.; de Almeida, L.C.G.; Ribeiro, C.J.N.; dos Santos Silva, G.W.; Machuca-Contreras, F.A.; et al. Exploring self-care practices and health beliefs among men in the context of emerging infectious diseases: Lessons from the Mpox pandemic in Brazil. Nurs. Inq. 2024, 31, e12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpino, T.; Atkins, K.; Wiginton, J.M.; Murray, S.M.; Lucas, I.L.; Delaney, K.P.; Schwartz, S.; Sanchez, T.; Baral, S. Mpox stigma during the 2022 outbreak among men who have sex with men in the United States. Stigma Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Z.Y.S.; Chong, S.Y.; Niaupari, S.; Harrison-Quintana, J.; Lim, J.T.; Dickens, B.; Kularathne, Y.; Wong, C.S.; Tan, R.K.J. Receptiveness to monkeypox vaccines and public health communication strategies among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Singapore: Cross-sectional quantitative and qualitative insights. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2024, 100, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Barrita, A.; Wong-Padoongpatt, G. Predictors of the Fear of Monkeypox in Sexual Minorities. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2024, 11, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Fox, A.M. Communities at Risk for Mpox and Stigmatizing Policies: A Randomized Survey, Republic of Korea, 2022. Am. J. Public Health 2023, 113, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, M.; Salcedo, M.; Mora, M.; Siguier, M.; Velter, A.; Leclercq, V.; Girard, G. Negotiating Access to Healthcare and Experience of Stigma Among Cisgender Gay Men Diagnosed with Mpox During the 2022 Epidemic in France: A Qualitative Study. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 2831–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, V.S.; Rajkhowa, P.; Mallya, B.R.; Raksha, D.S.; Mrinalini, V.; Cauvery, K.; Raj, R.; Toby, I.; Pattanshetty, S.; Brand, H. A sentiment and content analysis of tweets on monkeypox stigma among the LGBTQ+ community: A cue to risk communication plan. Dialogues Health 2023, 2, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gairal-Casadó, R.; Ríos-González, O.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Burgués-Freitas, A. The Role of Social Networks to Counteract Stigmatization Toward Gay and Bisexual Men. Qual. Res. Educ. 2023, 12, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, J.; Comer, D.; Field, D.J.; Parlour, R.; Shanley, A.; Noone, C. Recognising and responding to the community needs of gay and bisexual men around mpox. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, H. How do people tweet about gay and bisexual people surrounding the 2022 monkeypox outbreak? An NLP-based text analysis of tweets in the US. Commun. Res. Rep. 2023, 40, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.; Halaly, A. Paralleling the Gay Man’s Trauma: Monkeypox Stigma and the Mainstream Media. J. Commun. Inq. 2024, 48, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, O.O.; Boyd, D.; Abu-Ba’are, G.R.; Egbunikeokye, J.; Wharton, M. “I Know They’re Going to Weaponize This:” Black and Latino Sexual Minority Men’s Mpox-Related Sexual Behaviors, Stigma Concerns, and Vaccination Barriers and Facilitators. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C. Mpox on Reddit: A Thematic Analysis of Online Posts on Mpox on a Social Media Platform among Key Populations. J. Urban. Health 2023, 100, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.; Ai, J.; Vazirnia, P.; McLeish, T.; Krajco, C.; Moraga, R.; Quinn, K. A qualitative study of Chicago gay men and the Mpox outbreak of 2022 in the context of HIV/AIDS, PrEP, and COVID-19. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, K.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, W.; He, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Mpox risk perception and associated factors among Chinese young men who have sex with men: Results from a large cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnuji, M.; Schmidt-Sane, M.; Adegoke, O.; Abbas, S.; Shoyemi, E.; Lawanson, A.O.; Jegede, A.; MacGregor, H. Mpox and the men who have sex with men (MSM) community in Nigeria: Exploratory insights from MSM and persons providing healthcare services to them. Glob. Public Health 2025, 20, 2433725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutalek, R.; Grohma, P.; Maukner, A.C.; Wojczewski, S.; Palumbo, L.; Salvi, C. The role of RCCE-IM in the mpox response: A qualitative reflection process with experts and civil society in three European countries. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Forestier, J.; Skakoon-Sparling, S.; Page-Gould, E.; Chasteen, A. Experiences of Stigma Among Sexual Minority Men During the 2022 Global Mpox Outbreak. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Forestier, J.M.; Page-Gould, E.; Chasteen, A. Identity Concealment May Discourage Health-Seeking Behaviors: Evidence From Sexual-Minority Men During the 2022 Global Mpox Outbreak. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 35, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, W.; He, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Depressive symptoms and its multifaceted associated factors among young men who have sex with men facing the dual threats of COVID-19 and mpox in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 363, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Navarro, R.; Sanz-Muñoz, I.; Onecha-Vallejo, V.; Fernández-Espinilla, V.; Eiros, J.M.; Castrodeza-Sanz, J.; Prada-García, C. Psychosocial impact and stigma on men who have sex with men due to monkeypox. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1479680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Y. Mpox-related stigma and healthcare-seeking behavior among men who have sex with men. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2025, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, T.; Towler, L.; Smith, L.E.; Horwood, J.; Denford, S.; Rubin, G.J.; Hickman, M.; Amlôt, R.; Oliver, I.; Yardley, L. Mpox knowledge, behaviours and barriers to public health measures among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the UK: A qualitative study to inform public health guidance and messaging. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi Nia, Z.; Bragazzi, N.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Wu, J.; Kong, J. Mpox Panic, Infodemic, and Stigmatization of the Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual Community: Geospatial Analysis, Topic Modeling, and Sentiment Analysis of a Large, Multilingual Social Media Database. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, B.; Jaspal, R. Mpox in the news: Social representations, identity, stigma and coping. Med. Humanit. 2025, 51, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbajo, A.; Euceda, A.; Smith, J.; Ekundayo, R.; Wattree, J.; Brooks, M.; Hickson, D. Demographics and Health Beliefs of Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Sexual Minority Men Receiving a Mpox Vaccination in the United States. J. Urban. Health 2023, 100, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otmar, C.D.; Merolla, A.J. Social Determinants of Message Exposure and Health Anxiety Among Young Sexual Minority Men in the United States During the 2022 Mpox Outbreak. Health Commun. 2024, 40, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.; Hubach, R.D. An Exploratory Study of the Mpox Media Consumption, Attitudes, and Preferences of Sexual and Gender Minority People Assigned Male at Birth in the United States. LGBT Health 2023, 10, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe, A.M.; Castagnetto, J.M. Monkeypox in Latin America and the Caribbean: Assessment of the first 100 days of the 2022 outbreak. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.R.d.S.; Ribeiro, C.J.N.; Lima, S.V.M.A.; Neto, J.C.; de Sousa, A.R.; Bulcao, C.d.S.; Dellagostini, P.G.; Batista, O.M.A.; de Oliveira, L.B.; Mendes, I.A.C.; et al. Chemsex among men who have sex with men during the Mpox health crisis in Brazil: A nationwide web survey. Public Health Nurs. 2024, 41, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.R.d.S.; Ribeiro, C.J.N.; Santos Junior, J.F.C.D.; Almeida, V.S.; Nascimento, R.d.C.D.; Barreto, N.M.P.V.; de Sousa, A.R.; Bezerra-Santos, M.; Cepas, L.A.; Fernandes, A.P.M.; et al. Mpox Vaccine Hesitancy Among Brazilian Men Who Have Sex with Men: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzle, S.A.; Grant, M.; Lovelace, S.; Jung, J.; Choate, C.; Guerin, J.; Weinstein, W.; Taylor, G. Survey of pain and stigma experiences in people diagnosed with mpox in Baltimore, Maryland during 2022 global outbreak. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-H.; Chang, H.-H.; Tou, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Huang, K.-C.; Lu, C.-W. Stigmatization and Preferences in Monkeypox Vaccine Regimens. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2024, 53, 3825–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.J.; Storer, D.; Lancaster, K.; Haire, B.; Newman, C.E.; Paparini, S.; MacGibbon, J.; Cornelisse, V.J.; Broady, T.R.; Lockwood, T.; et al. Mpox Illness Narratives: Stigmatising Care and Recovery During and After an Emergency Outbreak. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, B.P.; Kirklewski, S.J.; Griffith, F.J.; Gibbs, J.J.; Lauckner, C.K.; Nicholson, E.; Tengatenga, C.; Hansen, N.B.; Kershaw, T. “It’s another gay disease”: An intersectional qualitative approach contextualizing the lived experiences of young gay, bisexual, and other sexual minoritized men in the United States during the mpox outbreak. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, T.S.; Silva, M.S.T.; Coutinho, C.; Hoagland, B.; Jalil, E.M.; Cardoso, S.W.; Moreira, J.; Magalhaes, M.A.; Luz, P.M.; Veloso, V.G.; et al. Evaluation of Mpox Knowledge, Stigma, and Willingness to Vaccinate for Mpox: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Among Sexual and Gender Minorities. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 9, e46489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turpin, R.E.; Mandell, C.J.; Camp, A.D.; Davidson Mhonde, R.R.; Dyer, T.V.; Mayer, K.H.; Liu, H.; Coates, T.; Boekeloo, B.O. Monkeypox-Related Stigma and Vaccine Challenges as a Barrier to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Black Sexual Minority Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, T.C.; Ghobrial, A.; Palich, R.; Charles, H.; Rodger, A.J.; Sabin, C.; Sparrowhawk, A.; Pool, E.R.M.; Prochazka, M.; Vivancos, R.; et al. Experiences of mpox illness and case management among cis and trans gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in England: A qualitative study. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 70, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Jiao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, W.; He, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Behavioral intentions of self-isolation and informing close contacts after developing mpox-related symptoms among young men who have sex with men in China. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Choi, Y.; Gahler, H. Sexual Stigma, Descriptive Norms, and U.S. Gay and Bisexual Men’s Intentions to Perform Mpox Preventive Behaviors. Health Commun. 2025, 40, 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qi, X.; Yang, L.; Meng, X.; Xu, G.; Luo, S.; Wu, K.; Tang, J.; Wang, B.; Fu, L.; et al. Mpox patients’ experience from infection to treatment and implications for prevention and control: A multicenter qualitative study in China. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Xu, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, F.; Cai, Y. Psychosocial correlates of free Mpox vaccination intention among men who have sex with men in China: Model construction and validation. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, H.M.L.; Gültzow, T.; Marcos, T.A.; Wang, H.; Jonas, K.J.; Stutterheim, S.E. Mpox stigma among men who have sex with men in the Netherlands: Underlying beliefs and comparisons across other commonly stigmatized infections. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Qi, X.; Han, B.; Fu, L.; Wang, B.; Wu, K.; Hong, Z.; Yang, L.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Efforts made, challenges faced, and recommendations provided by stakeholders involved in mpox prevention and control in China: A qualitative study. Public Health 2024, 236, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, H.; Robinson, M.; Lee, E.O.J.; Salway, T.; Ross, L.E. Beyond the Rainbow: Advancing 2S/LGBTQ+ Health Equity at a Time of Political Volatility. HealthcarePapers 2024, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalepe, L.M.; Maake, T.B. A Scoping Review of Heteronormativity in Healthcare and Its Implications on the Health and Well-Being of LGBTIQ+ Persons in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.; Paul, A.; Trivedi, V.; Bhatnagar, R.; Bhalsinge, R.; Jadhav, S.V. Global epidemiology, viral evolution, and public health responses: A systematic review on Mpox (1958–2024). J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Kumar, N.; Singh, K.; Byrareddy, S.N. Mpox in MSM: Tackling stigma, minimizing risk factors, exploring pathogenesis, and treatment approaches. Biomed. J. 2025, 48, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, D.; Fessler, D.M.T.; Lerman, K.; Burghardt, K. X under Musk’s leadership: Substantial hate and no reduction in inauthentic activity. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, A.M.; Ruiz-Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Sánchez, F.J. Mapping Homophobia and Transphobia on Social Media. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2024, 21, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, P.; Stoeckl, K. The Global Resistance to LGBTIQ Rights. J. Democr. 2024, 35, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoefer, C.D.; Xue, B.; Poznańska, A. Implications of the decline in LGBT rights for population mental health: Evidence from Polish “LGBT-free zones”. J. Health Econ. 2025, 100, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinan, C. From criminalization to erasure: Project 2025 and anti-trans legislation in the US. Crime Media Cult. 2025, 21, 17416590241312149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, A.; Cheyne, A.; Tulunay, H.; Orkin, C.; Nutland, W.; Dunning, J.; Stolow, J.; Gobat, N.; Olliaro, P.; Rojek, A.; et al. Mpox stigma in the UK and implications for future outbreak control: A cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.S.; Mansergh, G.; Lynch, J.; Santibanez, S. Addressing Disease-Related Stigma During Infectious Disease Outbreaks. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsini, D.; Sartini, M.; Spagnolo, A.M.; Cristina, M.L.; Martini, M. Mpox: “the stigma is as dangerous as the virus”. Historical, Social, Ethical Issues and Future forthcoming. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2024, 64, E398–E404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obasa, A.E.; Botes, M.; Kleinsmidt, A.; Staunton, C. Mpox and the Ethics of Outbreak Management: Lessons for Future Public Health Crises. Dev. World Bioeth. 2025; dewb.70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; Van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barré, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, Y.J.; Schneider, F.; Widdershoven, V.; Goense, C.J.D.; Peters, C.M.M.; Van Elsen, S.G.; Hoebe, C.J.P.A.; Dukers-Muijrers, N.H.T.M. Using a theoretical framework of Intervention Mapping to inform public health communication messages designed to increase vaccination uptake; the example of mpox in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjar, W.M.; Alaqeel, M.K. Monkeypox stigma and risk communication; Understanding the dilemma. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, L.; Picchio, C.A.; Barbier, F.; Calderon-Cifuentes, A.; James, J.; Lunchenkov, N.; Nutland, W.; Owen, G.; Orkin, C.; Rocha, M.; et al. Co-creating a Mpox Elimination Campaign in the WHO European Region: The Central Role of Affected Communities. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.; Roth, N.M.; Gold, J.A.W.; Pao, L.Z.; Olansky, E.; Torrone, E.A.; McClung, R.P.; Ellington, S.R.; Delaney, K.P.; Carnes, N.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Mpox in Transgender and Gender-Diverse Adults—United States, May–November 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Country or Region of Study | Study Design | Population | Sample Size | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agroia et al., 2025 [29] | United States | Qualitative | GBMSM and transgender | 47 | Mpox vaccine hesitancy |

| Bergman et al., 2022 [30] | United States | Case study | GBMSM | 1 | Nursing interventions for mpox stigma prevention |

| Biesty et al., 2024 [31] | United Kingdom | Qualitative (interviews and workshops) | GBMSM and community leaders | Unspecified | Community-led interventions to reduce stigma and build trust |

| Bulcão et al., 2024 [32] | Brazil | Qualitative (online survey) | GBMSM | 67 | Health vulnerability in the context of the mpox epidemic |

| Bulcão et al., 2024 [33] | Brazil | Qualitative (online survey) | MSM | 727 | Self-care promotion in the context of mpox transmission |

| Carpino et al., 2025 [34] | United States | Cross-sectional study (online survey) | GBMSM | 824 | Mpox-related stigma among social networks with higher exposure to mpox |

| Chan et al., 2024 [35] | Singapore | Cross-sectional study (online survey) | GBMSM | 237 | Mpox vaccine willingness and vaccine-related communications |

| Chang et al., 2024 [36] | United States | Cross-sectional study (online study) | Sexual minority (SM) | 79 | Mpox fear and experiences of violence and discrimination |

| Choi et al., 2023 [37] | Republic of Korea | Randomised control trial (survey experiment) | Adults | 1500 | Risk perceptions, vaccine acceptance, and support for stigmatising policies through different communications strategies |

| Dos Santos et al., 2025 [38] | France | Qualitative (panel interviews) | Gay cisgender men | 7 | Barriers to accessing care and managing disease symptoms |

| Dsouza et al., 2023 [39] | Global, not specified | Qualitative (natural language processing) | LGBTQ+ community on Twitter | 70,832 * | Online stigma against mpox among the LGBTQ+ community |

| Gairal-Casadó et al., 2023 [40] | Spain | Qualitative (social media analytics) | Online community engaged in mpox discourse | 2313 * | Influences of global communication strategies on public discourse regarding mpox and MSM |

| Gilmore et al., 2024 [41] | Ireland | Qualitative (online survey) | GBMSM | 163 | Fear, othering, and mpox-related information consumption patterns |

| Gim, 2023 [42] | United States | Qualitative (natural language processing) | Online community engaged in mpox discourse | 23,734 * | Mpox-related stigma communication online |

| Grant and Halaly, 2024 [43] | United States | Media content analysis | Media representations of GBMSM | Unspecified | Media representation and its role in reinforcing stigma |

| Harris et al., 2025 [44] | United States | Qualitative (interviews) | Black and Latino SM men (BLSMM) | 41 | Negative impacts of mpox-related stigma, vaccine scepticism, and poor communication and outreach efforts |

| Hong, 2023 [45] | Not applicable | Media content analysis | GBMSM | 809 * | Anonymous discussion forum provides safe space for GBMSM to gather information without fear of exposure |

| Hughes et al., 2024 [46] | United States | Qualitative (interviews) | Gay men | 30 | Widespread mpox vaccine support and acceptability as a community health measure despite ongoing barriers to access |

| Jiao et al., 2023 [47] | China | Cross-sectional study (online survey) | GBMSM | 2493 | High perceived severity coupled with low perceived susceptibility indicates need for better, non-stigmatising risk communication |

| Kunnuji et al., 2024 [48] | Nigeria | Qualitative (interviews) | GBMSM/MSM | 28 | Sociolegal contexts influence awareness and knowledge about mpox, and experience seeking mpox-related care |

| Kutalek et al., 2025 [49] | Poland, Serbia, and Spain | Qualitative (interviews) | GBMSM | 19 | A multipronged, collaborative, and intersectoral approach to communication and mitigating stigma associated with challenging sociopolitical dynamics |

| Le Forestier et al., 2024 [50] | Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and United States | Longitudinal study (survey) | SMM | 685 | The impacts of stigmatising health communication on well-being among higher risk groups |

| Le Forestier et al., 2024 [51] | Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and United States | Longitudinal study (survey) | SMM | 685 | Stigma impacts utilisation of public health measures |

| Li et al., 2024 [52] | China | Cross-sectional survey | Young MSM (YMSM) | 2493 | Mental health challenges among YMSM during concurrent public health crises |

| Linares-Navarro et al., 2025 [53] | Spain | Cross-sectional survey | MSM with and without mpox diagnosis | 115 | Psychosocial impact and stigma experiences among MSM in Spain |

| Liu et al., 2025 [54] | China | Cross-sectional survey | MSM | 356 | Healthcare-seeking behaviour and stigma in Chinese MSM |

| May et al., 2023 [55] | United Kingdom | Qualitative interviews | GBMSM | 44 | Public health messaging, stigma, and behaviour change |

| Movahedi Nia et al., 2023 [56] | Canada, India, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States | Media content analysis | GBMSM | 125,424 * | Mpox-related stigmatisation on popular social media platforms |

| Nerlich and Jaspal, 2025 [57] | Not applicable | Media content analysis | GBMSM | 91 * | Social representations of mpox |

| Ogunbajo et al., 2023 [58] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | Black SMM (BSMM) | 178 | Mpox vaccine acceptability and access |

| Otmar and Merolla, 2025 [59] | United States | Longitudinal survey | GBMSM | 254 | Social determinants of health and impact of mpox on mental health |

| Owens and Hubach, 2023 [60] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | Sexual and gender minority (SGM) assigned male at birth (AMAB) | 496 | Consumption and attitudes towards mpox-related media |

| Quispe and Castagnetto, 2023 [61] | Latin America and the Caribbean | Mixed methods | GBMSM | Unspecified | Challenges controlling mpox transmission |

| Santos et al., 2024 [62] | Brazil | Cross-sectional survey | MSM | 1452 | Intersection of chemsex and public health |

| Santos et al., 2024 [63] | Brazil | Cross-sectional survey | MSM | 1449 | Factors associated with mpox vaccine hesitancy |

| Schmalzle et al., 2024 [64] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | MSM with mpox diagnosis | 32 | Stigma experiences among MSM diagnosed with mpox |

| Shen et al., 2024 [65] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional survey | MSM receiving mpox vaccination | 2827 | Vaccine-related stigma and preferences for injection site |

| Smith et al., 2024 [66] | Australia | Qualitative interviews | GBMSM | 16 | Experiences among people diagnosed with mpox or in close proximity to someone diagnosed with mpox |

| Takenaka et al., 2024 [67] | United States | Qualitative interviews | Gay, bisexual, and other sexually minoritised men (GBSMM) | 33 | Experiences with the mpox outbreak |

| Torres et al., 2023 [68] | Brazil | Cross-sectional online survey | Sexual and gender minorities (mostly GBMSM) | 6236 | Knowledge, stigma, and willingness to vaccinate in SGM |

| Turpin et al., 2023 [69] | United States | Qualitative interviews | BSMM | 24 | Experiences and perceptions of mpox, mpox-related stigma, and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) engagement |

| Witzel et al., 2024 [70] | United Kingdom | Qualitative interviews | Cisgender and transgender GBMSM diagnosed with mpox and clinical/community-based stakeholders | 26 | Experiences associated with mpox and clinical and social support needs |

| Xu et al., 2024 [71] | China | Cross-sectional survey | YMSM | 2493 | Self-isolation and other risk mitigation behaviours among YMSM diagnosed with mpox |

| Yang et al., 2025 [72] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | GBMSM | 439 | Mpox perceptions and preventive behaviours |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [73] | China | Qualitative interviews | GBMSM | 15 | Mpox patient experiences and advice for control and prevention of spread |

| Zhang et al., 2025 [74] | China | Cross-sectional survey | MSM | 2403 | Psychosocial correlates of mpox vaccination |

| Zimmermann et al., 2023 [75] | Netherlands | Cross-sectional survey | MSM | 394 | Anticipated stigma and comparison with other infections |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berger, M.N.; Cassidy-Matthews, C.; Farag, M.W.A.; Davies, C.; Bopage, R.I.; Sawleshwarkar, S. Mpox-Related Stigma Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212690

Berger MN, Cassidy-Matthews C, Farag MWA, Davies C, Bopage RI, Sawleshwarkar S. Mpox-Related Stigma Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212690

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerger, Matthew N., Chenoa Cassidy-Matthews, Marian W. A. Farag, Cristyn Davies, Rohan I. Bopage, and Shailendra Sawleshwarkar. 2025. "Mpox-Related Stigma Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Narrative Review" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212690

APA StyleBerger, M. N., Cassidy-Matthews, C., Farag, M. W. A., Davies, C., Bopage, R. I., & Sawleshwarkar, S. (2025). Mpox-Related Stigma Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 13(21), 2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212690