Quantitatively Evaluate the Improvement of Functional Cure for the Quality of Life of Chronic Hepatitis B Cases: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Selection

2.2. Study Population and Sample Size

2.2.1. Functional Cure

2.2.2. CHB with Antiviral Treatment Group

2.2.3. Healthy Control Group

2.3. Data Collection and Quality Control

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Subjects’ Characteristics

3.2. Adjusted and Unadjusted Results on Eight Health Domains Scores

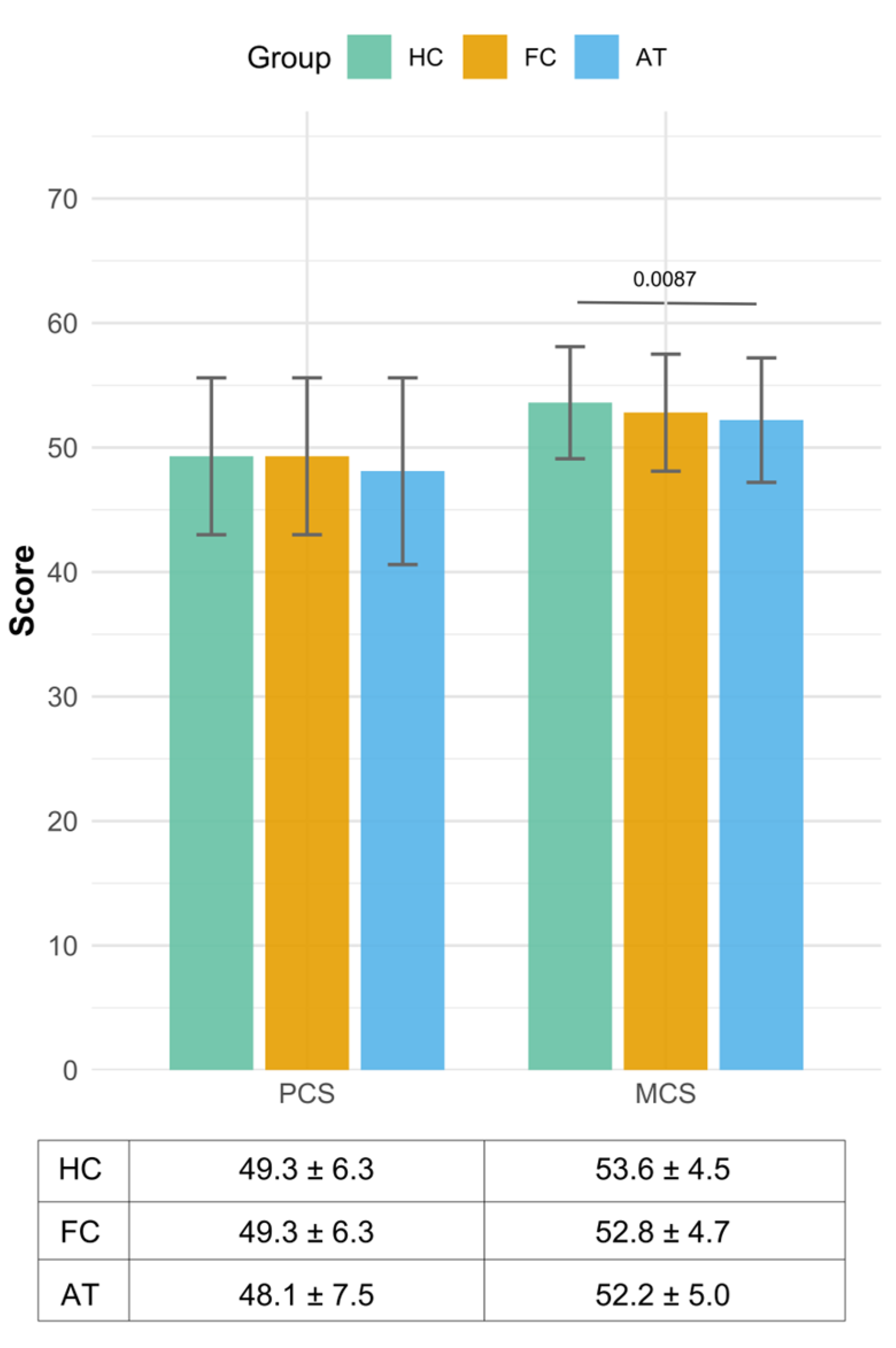

3.3. The Results of Two Summary Measures—Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHB | Chronic hepatitis B |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| SF-36-V2 | Chinese Short Form-36 version 2 |

References

- WHO. Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi-Shearer, D.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Nguyen, M.H.; Chen, D.S.; Van Damme, P.; Abbas, Z.; Abdulla, M.; Abou Rached, A.; Adda, D.; Aho, I.; et al. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, F.; Wong, N.K.; He, J.; Zhang, R.; Sun, R.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Koike, K.; et al. Global liver disease burdens and research trends: Analysis from a Chinese perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Shen, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Miao, N.; Li, J.; Ding, G.; et al. New progress in HBV control and the cascade of health care for people living with HBV in China: Evidence from the fourth national serological survey 2020. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2024, 51, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, R.M.; Bassit, L.C.; Tao, S.J.; Jiang, Y.; Ferreira, A.S.; Hori, P.C.; Ganova-Raeva, L.M.; Khudyakov, Y.; Schinazi, R.F.; Carrilho, F.J.; et al. Long-term virological and adherence outcomes to antiviral treatment in a 4-year cohort chronic HBV study. Antivir. Ther. 2019, 24, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Society of Infectious Disease; Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Medical Association. The expert consensus on clinical cure (functional cure) of chronic hepatitis B. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2019, 35, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Kao, J.H.; Piratvisuth, T.; Wang, X.; Kennedy, P.T.; Otsuka, M.; Ahn, S.H.; Tanaka, Y.; Wang, G.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Update on the treatment navigation for functional cure of chronic hepatitis B: Expert consensus 2.0. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, S134–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.C.; Wong, G.L.; Chan, H.L.; Tse, Y.-K.; Lam, K.L.-Y.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Wong, V.W.-S. HBsAg seroclearance further reduces hepatocellular carcinoma risk after complete viral suppression with nucleos(t)ide analogues. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.A.; Kim, S.U.; Sinn, D.H.; Jang, J.W.; Lim, Y.S.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, J.H. Discontinuation of nucleos(t)ide analogues is not associated with a higher risk of HBsAg seroreversion after antiviral-induced HBsAg seroclearance: A nationwide multicentre study. Gut 2020, 69, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.Q. Ning, Toward a cure for hepatitis B virus Infection: Combination therapy involving viral suppression and immune modulation and long-term outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S771–S777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.; Dezanet, L.N.; Lacombe, K. Functional cure of hepatitis B virus infection in individuals with HIV-coinfection: A literature review. Viruses 2021, 13, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.X.; Lambert, G.; Cook, A.; Ndow, G.; Haddadin, Y.; Shimakawa, Y.; Hallett, T.B.; Harvala, H.; Sicuri, E.; Lemoine, M.; et al. Quality of life in patients with HBV infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.X. The Relationship Between Quality of Life, Fatigue and Nucleos(t)ide Analog Antiviral Treatment in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in Guangzhou. Master’s Thesis, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Zhong, C.; Tang, Q.; Xie, H.; Gao, X.; Li, B.; Yin, J.; Wei, L. Beyond the liver: Well-being as the bridge between fatigue and quality of life in chronic hepatitis B patients. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1535916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Jin, C.; Li, Y.; Tu, M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.-F.; et al. Health-related quality of life and its influencing factors in patients with hepatitis B: A cross-sectional assessment in southeastern China. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 2021, 9937591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, K.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, X. Significant impairment of health-related quality of life in mainland Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B: A cross-sectional survey with pair-matched healthy controls. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.N.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Q.; Ji, Z.H.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhuang, G.H. Reliability, validity and sensitivity of the Chinese (simple) short form 36 health survey version 2 (SF-36v2) in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J. Viral Hepat. 2013, 20, e47–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.M. Psychometric Evaluation, Norms, Application to Chronic Conditions of the Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey in Chinese Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Revill, P.A.; Chisari, F.V.; Block, J.M.; Dandri, M.; Gehring, A.J.; Guo, H.; Hu, J.; Kramvis, A.; Lampertico, P.; A Janssen, H.L.; et al. A global scientific strategy to cure hepatitis B. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases; Chinese Medical Association. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B: A 2015 update. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 23, 888–905. [Google Scholar]

- Lok, A.S.; Zoulim, F.; Dusheiko, G.; Ghany, M.G. Hepatitis B cure: From discovery to regulatory approval. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsounis, E.P.; Tourkochristou, E.; Mouzaki, A.; Triantos, C. Toward a new era of hepatitis B virus therapeutics: The pursuit of a functional cure. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2727–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, A. Transaminase elevations during treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection: Safety considerations and role in achieving functional cure. Viruses 2021, 13, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y.G.; Fan, Z.H.; Shen, D.; Huang, X.; Yu, Q.; Liu, M.; Ren, F.; Wang, X.; Dai, L.; et al. Assessing health-related quality of life and health utilities in patients with chronic hepatitis B-related diseases in China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronkjær, L.L.; Lauridsen, M.M. Quality of life and unmet needs in patients with chronic liver disease: A mixed-method systematic review. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, P.A.; Conti, S.; Scalone, L.; Jaffe, A.; Ciaccio, A.; Okolicsanyi, S.; Rota, M.; Fabris, L.; Colledan, M.; Fagiuoli, S.; et al. Health related quality of life in chronic liver diseases. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 2630–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Palmer, J.; Cerri, K.; Sbarigia, U.; Chan, E.K.; Pollock, R.F.; Valentine, W.J.; Bonroy, K. Impact of stigma on people lving with chronic hepatitis B. Patient-Relat. Outcome Meas. 2020, 11, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yozgat, A.; Can, G.; Can, H.; Ekmen, N.; Akyol, T.; Kasapoglu, B.; Kekilli, M. Social stigmatization in Turkish patients with chronic hepatitis B and C. Gastroenterol. Y Hepatol. 2021, 44, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeland, C.; Racho, R.; Kamischke, M.; Moraras, K.; Wang, E.; Cohen, C. Cure everyone and vaccinate the rest: The patient perspective on future hepatitis B treatment. J. Viral Hepat. 2021, 28, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacaer, Z.; Cakir, B.; Erdem, H.; Ugurlu, K.; Durmus, G.; Ince, N.K.; Ozturk, C.; Hasbun, R.; Batirel, A.; Yilmaz, E.M.; et al. Quality of life and related factors among chronic hepatitis B-infected patients: A multi-center study, Turkey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.N.; Hong, J.; Zhou, J.L.; Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Xie, W.; Piao, H.; Xu, X.; Jiang, W.; Feng, B.; et al. Health-related quality of life improves after entecavir treatment in patients with compensated HBV cirrhosis. Hepatol. Int. 2021, 15, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantrakul, R.; Sripongpun, P.; Pattarapuntakul, T.; Chamroonkul, N.; Kongkamol, C.; Phisalprapa, P.; Kaewdech, A. Health-related quality of life in Thai patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterol Rep. 2024, 12, goae015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahassadi, A.K.; Machekam, O.; Attia, A.K. The impact of virologic parameters and liver fibrosis on Health-Related Quality of Life in black African patients with chronic hepatitis B: Results from a high endemic area. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Siddiqui, M.; Malhotra, S.; Maaz, M. Unani formulation improved quality of life in Indian patients of chronic hepatitis B. J. Young Pharm. 2019, 11, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Lu, Q.B.; Shang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, F. Cost-effectiveness of expanded antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis B virus infection in China: An economic evaluation. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2023, 35, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total (N = 497) | Functional Cure (n = 163) | CHB Patients with Antiviral Treatment (n = 192) | Healthy Control (n = 142) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region * | ||||

| East | 171 (34.4) | 50 (30.7) | 75 (39.1) | 46 (32.4) |

| Middle | 147 (29.6) | 51 (31.3) | 46 (24.0) | 50 (35.2) |

| West | 179 (36.0) | 62 (38.0) | 71 (37.0) | 46 (32.4) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 283 (57.1) | 100 (61.3) | 128 (66.7) | 86(61.0) |

| Female | 213 (42.9) | 63 (38.7) | 64 (33.3) | 55 (39.0) |

| Age group * (Mean ± SD) | 37.3 ± 8.7 | 38.9 ± 8.6 | 38.7 ± 8.0 | 33.5 ± 8.8 |

| <40 years | 285 (57.3) | 80 (49.1) | 100 (52.1) | 105 (73.9) |

| ≥40 years | 212 (42.7) | 83 (50.9) | 92 (47.9) | 37 (26.1) |

| Education | ||||

| High school and below | 288 (57.9) | 93 (57.1) | 111 (57.8) | 84 (59.2) |

| Graduate | 209 (42.1) | 70 (42.9) | 81 (42.2) | 58 (40.8) |

| Marriage | ||||

| Unmarried | 74 (14.9) | 20 (12.3) | 28 (14.6) | 26 (18.3) |

| Married | 414 (83.3) | 140 (85.9) | 162 (84.4) | 112 (78.9) |

| Divorced/widowed | 9 (1.8) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.8) |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable Entered in the Model | Standardized Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | 0.012 | −0.016, 0.040 | 0.405 | |

| West | 0.018 | −0.007, 0.044 | 0.158 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.015 | −0.038, 0.007 | 0.176 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.010 | −0.043, 0.014 | 0.316 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.005 | −0.036, 0.016 | 0.459 | |

| Role physical | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.016 | −0.051, 0.02 | 0.388 | |

| West | −0.005 | −0.038, 0.028 | 0.756 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | 0.002 | −0.026, 0.03 | 0.898 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.003 | −0.036, 0.031 | 0.865 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.007 | −0.024, 0.046 | 0.546 | |

| Bodily pain | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.037 | −0.083, 0.009 | 0.113 | |

| West | 0 | −0.045, 0.045 | 0.995 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.006 | −0.046, 0.034 | 0.768 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | 0.028 | −0.019, 0.075 | 0.244 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.001 | −0.049, 0.05 | 0.984 | |

| General health | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.003 | −0.047, 0.040 | 0.878 | |

| West | 0.029 | −0.012, 0.071 | 0.166 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.015 | −0.051, 0.020 | 0.399 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.052 | −0.094, −0.010 | 0.015 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.127 | −0.170, −0.083 | <0.001 | |

| Vitality | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.023 | −0.062, 0.015 | 0.232 | |

| West | −0.005 | −0.047, 0.036 | 0.797 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | 0.008 | −0.026, 0.042 | 0.642 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.030 | −0.070, 0.011 | 0.151 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.048 | −0.089, −0.007 | 0.023 | |

| Social functioning | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.016 | −0.064, 0.033 | 0.525 | |

| West | −0.001 | −0.047, 0.044 | 0.958 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.011 | −0.05, 0.028 | 0.578 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | 0.015 | −0.009, 0.024 | 0.183 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.034 | −0.045, 0.052 | 0.174 | |

| Role emotional | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.035 | −0.082, 0.013 | 0.152 | |

| West | −0.018 | −0.064, 0.027 | 0.433 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | 0.012 | −0.027, 0.050 | 0.560 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.001 | −0.043, 0.053 | 0.837 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.003 | −0.048, 0.047 | 0.973 | |

| Mental health | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.046 | −0.096, 0.003 | 0.067 | |

| West | −0.002 | −0.05, 0.047 | 0.949 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | 0.011 | −0.031, 0.053 | 0.617 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.006 | −0.057, 0.045 | 0.816 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.029 | −0.081, 0.024 | 0.287 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable Entered in the Model | Standardized Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical composite summary | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | 0.001 | −0.031, 0.033 | 0.948 | |

| West | 0.013 | −0.017, 0.042 | 0.395 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.017 | −0.042, 0.009 | 0.201 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | 0.012 | −0.019, 0.044 | 0.436 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.009 | −0.041, 0.022 | 0.559 | |

| Mental composite summary | Region | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.013 | −0.032, 0.005 | 0.156 | |

| West | −0.003 | −0.023, 0.017 | 0.782 | |

| Age group | ||||

| <40 years | Reference | |||

| ≥40 years | 0.0003 | −0.016, 0.017 | 0.975 | |

| Group | ||||

| Healthy control | Reference | |||

| Functional cure | −0.001 | −0.019, 0.022 | 0.899 | |

| CHB with antiviral treatment | −0.023 | −0.042, −0.003 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Gao, Z.; Li, H.; Kang, Y.; Fu, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, H.; Zheng, H.; et al. Quantitatively Evaluate the Improvement of Functional Cure for the Quality of Life of Chronic Hepatitis B Cases: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2590. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202590

Zhang S, Gao Z, Li H, Kang Y, Fu L, Chen X, Xu X, Chen X, Zhuang H, Zheng H, et al. Quantitatively Evaluate the Improvement of Functional Cure for the Quality of Life of Chronic Hepatitis B Cases: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2590. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202590

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Sihui, Zhiliang Gao, Hui Li, Yi Kang, Lei Fu, Xuebing Chen, Xiaoyuan Xu, Xinyue Chen, Hui Zhuang, Hui Zheng, and et al. 2025. "Quantitatively Evaluate the Improvement of Functional Cure for the Quality of Life of Chronic Hepatitis B Cases: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2590. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202590

APA StyleZhang, S., Gao, Z., Li, H., Kang, Y., Fu, L., Chen, X., Xu, X., Chen, X., Zhuang, H., Zheng, H., & Cui, F. (2025). Quantitatively Evaluate the Improvement of Functional Cure for the Quality of Life of Chronic Hepatitis B Cases: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in China. Healthcare, 13(20), 2590. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202590