Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility Quality of Life in Infertile Women: Mediating Roles of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of This Study

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Samples

2.2. Study Tools

2.2.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire

2.2.2. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10)

2.2.3. Chinese Version of the Infertility Self-Efficacy Scale (ISE)

2.2.4. Copenhagen Multi-Centre Psychosocial Infertility (COMPI) Coping Strategy Scale

2.2.5. Fertility Quality of Life Scale (FertiQoL)

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Univariate Analysis of Resilience, Infertility Self-Efficacy, Infertility Coping Strategy, and Fertility Quality of Life

3.2.1. Resilience

3.2.2. Infertility Self-Efficacy

3.2.3. Infertility Coping Strategy

3.2.4. Fertility Quality of Life

3.3. Correlation Between Resilience, Infertility Self-Efficacy, Infertility Coping Strategy, and Fertility Quality of Life

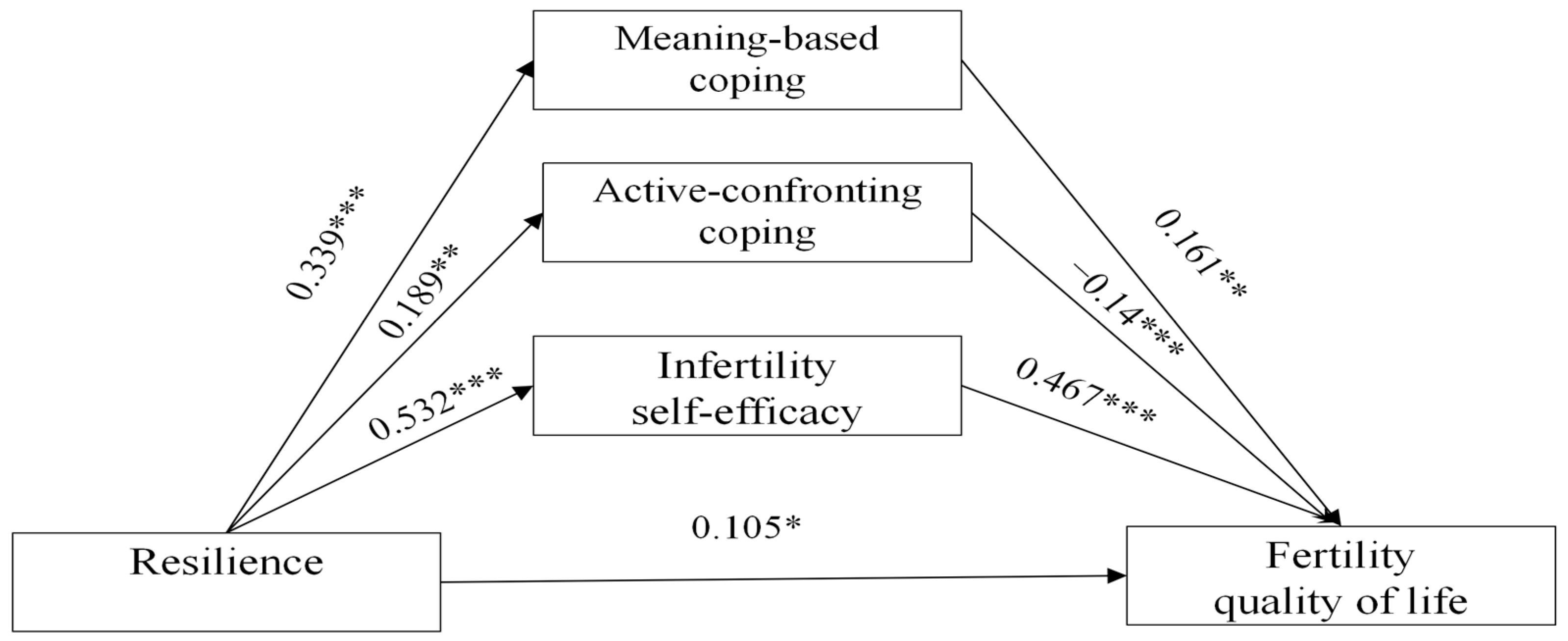

3.4. Mediating Effect of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping Strategy on the Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility QoL

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Infertility. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Sun, H.; Gong, T.T.; Jiang, Y.T.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wu, Q.J. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: Results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging 2019, 11, 10952–10991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 1 in 6 People Globally Affected by Infertility: WHO. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-04-2023-1-in-6-people-globally-affected-by-infertility (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Li, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Qian, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Jin, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, B.; et al. Fertility history and intentions of married women, China. Bull. World Health Organ. 2024, 102, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ren, Y.; Niu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, P.; Li, L. The impact of stigma on mental health and quality of life of infertile women: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1093459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, F.W.; Loke, A.Y. Relationships between infertility-related stress, family sense of coherence and quality of life of couples with infertility. Hum. Fertil. 2022, 25, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, F.; Salvatori, P.; Cipriani, L.; Damiano, G.; Dirodi, M.; Trombini, E.; Rossi, N.; Porcu, E. Self-efficacy, coping strategies and quality of life in women and men requiring assisted reproductive technology treatments for anatomical or non-anatomical infertility. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhwal, V.; Choudhary, V.; Perumal, V.; Bhattacharya, D. Depression, anxiety, quality of life and coping in women with infertility: A cross-sectional study from India. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 158, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Gu, W.; Xu, X.; Yan, C.; Jiao, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. Stigma predicting fertility quality of life among Chinese infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 43, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagórska, M.; Lesińska-Sawicka, M.; Obrzut, B.; Ulman, D.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D.; Zych, B. Health Related Behaviors and Life Satisfaction in Patients Undergoing Infertility Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wdowiak, A.; Anusiewicz, A.; Bakalczuk, G.; Raczkiewicz, D.; Janczyk, P.; Makara-Studzińska, M. Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zheng, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, K.; Cheng, C.; Jiang, H. Psychological Distress, Dyadic Coping, and Quality of Life in Infertile Clients Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technology in China: A Single-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 2715–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Dou, S.; Qin, W.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.; Guan, Y.; Tian, P. Association between quality of life and resilience in infertile patients: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1345899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Tong, C.; Huang, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, A. The analysis of fertility quality of life and the influencing factors of patients with repeated implantation failure. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, Z.; Han, X.; Shang, X.; Tian, W.; Kang, X.; Fang, M. A moderated mediation model of perceived stress, negative emotions and mindfulness on fertility quality of life in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1775–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Steen, T.A.; Seligman, M.E. Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Ali, K.; Kahathuduwa, C.; Baronia, R.; Ibrahim, Y. Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions on the Treatment of Depression. Cureus 2022, 14, e21933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A.K.; Ketcher, D.; Reblin, M.; Terrill, A.L. Positive Psychology Approaches to Interventions for Cancer Dyads: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.Y.; Ban, S.H. Effect of resilience on infertile couples’ quality of life: An actor-partner interdependence model approach. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, R.M.; Bax, K.C.; Ashok, D.; McMurtry, C.M. Health-related quality of life in youth with abdominal pain: An examination of optimism and pain self-efficacy. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Ning, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Han, D.; Li, X. Perceived social support and coping style as mediators between resilience and health-related quality of life in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Shi, J.; Sznajder, K.K.; Yang, F.; Cui, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X. Positive effects of resilience and self-efficacy on World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument score among caregivers of stroke inpatients in China. Psychogeriatrics 2021, 21, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Fu, W.; Pang, R.; et al. A Lancet Commission on 70 years of women’s reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in China. Lancet 2021, 397, 2497–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 64, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousineau, T.M.; Green, T.C.; Corsini, E.A.; Barnard, T.; Seibring, A.R.; Domar, A.D. Development and validation of the Infertility Self-Efficacy scale. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 1684–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.; Christensen, U.; Holstein, B.E. The social epidemiology of coping with infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, J.; Takefman, J.; Braverman, A. The Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) tool: Development and general psychometric properties. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 409–415.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Diao, S.; Zhang, X.; Gou, X.; Zhu, X. Fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) among Chinese women undergoing frozen embryo transfer. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.E.; Jelin, A.; Hoon, A.H., Jr.; Wilms Floet, A.M.; Levey, E.; Graham, E.M. Assisted reproductive technology: Short- and long-term outcomes. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2023, 65, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.A.; Rambhatla, A.; Schon, S.; Agarwal, A.; Krawetz, S.A.; Dupree, J.M.; Avidor-Reiss, T. Male Infertility is a Women’s Health Issue-Research and Clinical Evaluation of Male Infertility Is Needed. Cells 2020, 9, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, M.; August, F.; Nanyaro, M.W.; Wangwe, P.; Kikula, A.; Balandya, B.; Ngarina, M.; Muganyizi, P. Quality of life and associated factors among infertile women attending infertility clinic at Mnazi Mmoja Hospital, Zanzibar. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarif Golbar Yazdi, H.; Aghamohammadian Sharbaf, H.; Kareshki, H.; Amirian, M. Psychosocial Consequences of Female Infertility in Iran: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 518961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, G.K.; Çakır, H.; Kut, E. Mediating Role of Social Support in Resilience and Quality of Life in Patients with Breast Cancer: Structural Equation Model Analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 8, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Yasini Ardekani, S.M.; Anvari, M.; Kalantari, A.; Yaghmaie, F.; Royani, Z. Resilience as the predictor of quality of life in the infertile couples as the most neglected and silent minorities. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2022, 40, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.H.; Shahnawaz, M.G.; Patel, A.; Kashyap, P.; Singh, C.B. Resilience among involuntarily childless couples and individuals undergoing infertility treatment: A systematic review. Hum. Fertil. 2023, 26, 1562–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Q.F.; Yang, G.L.; Yan, J. Self-Efficacy Intervention Programs in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Narrative Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 3397–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Zeng, T.; Wu, M.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, M.; Zhu, Z.; Lang, X. Infertility psychological distress in women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment: A grounded theory study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 3642–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Mróz, M.; Bień, A. Quality of life, social support and self-efficacy in women after a miscarriage. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, A.; Dawood, S. Social support, self-efficacy, cognitive coping and psychological distress in infertile women. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, S.L.; Zia, A. Mediating Role of Resilience on Quality of Life in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, A.; Solano, L.; Di Trani, M.; Ginobbi, F.; Minutolo, E.; Tambelli, R. The effects of an expressive writing intervention on pregnancy rates, alexithymia and psychophysical health during an assisted reproductive treatment. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, R.; Okuhara, T.; Okada, H.; Goto, E.; Sakakibara, K.; Kiuchi, T. Associations between Stigma, Cognitive Appraisals, Coping Strategies and Stress Responses among Japanese Women Undergoing Infertility Treatment. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Constituent Ratio/Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤35 | 259 | 82.5 |

| >36 | 55 | 17.5 | |

| Ethnicity | Han nationality | 307 | 97.8 |

| Minority | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Employment | Employed | 260 | 82.8 |

| Unemployed | 54 | 17.2 | |

| Education Level | Junior high school or below | 39 | 12.4 |

| High school | 64 | 20.4 | |

| College or university | 160 | 51.0 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 44 | 14.0 | |

| No data | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Average monthly income per family member (CNY) | <5000 | 63 | 20.1 |

| 5000 to 10,000 | 148 | 47.1 | |

| 10,001 to 15,000 | 54 | 17.2 | |

| >15,000 | 35 | 11.1 | |

| No data | 14 | 4.5 | |

| Number of children | 0 | 259 | 82.6 |

| 1 | 46 | 14.6 | |

| 2 | 8 | 2.5 | |

| No data | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Type of infertility | Primary | 179 | 57.0 |

| Secondary | 133 | 42.4 | |

| No data | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Duration of infertility diagnosis (years) | ≤1 | 156 | 49.7 |

| 1 to 2 | 53 | 16.9 | |

| 2 to 3 | 55 | 17.5 | |

| >3 | 49 | 15.6 | |

| No data | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Duration of fertility treatments (years) | ≤1 | 208 | 66.2 |

| 1 to 2 | 39 | 12.4 | |

| 2 to 3 | 30 | 9.6 | |

| >3 | 33 | 10.5 | |

| No data | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Embryo transfer cycle | 0 | 197 | 62.7 |

| 1 | 76 | 24.2 | |

| 2 | 23 | 7.3 | |

| 3 | 10 | 3.2 | |

| >3 | 8 | 2.6 |

| Variables | Resilience (Mean ± SD) | ISE (Mean ± SD) | COMPI (Mean ± SD) | FertiQoL (Mean ± SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active-Avoidance | Active-Confronting | Passive-Avoidance | Meaning-Based | Total FertiQoL | Core FertiQoL | Treatment FteriQoL | |||

| Total | 27.25 ± 6.14 | 107.93 ± 22.14 | 8.24 ± 2.33 | 15.31 ± 3.96 | 8.37 ± 2.38 | 14.01 ± 3.29 | 68.52 ± 12.51 | 70.70 ± 13.92 | 63.29 ± 12.08 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| ≤35 | 27.28 ± 6.12 | 108.4 ± 21.76 | 8.21 ± 2.35 | 15.21 ± 3.85 | 8.44 ± 2.34 | 14.08 ± 3.26 | 68.71 ± 12.02 | 70.93 ± 13.64 | 63.38 ± 12.19 |

| >36 | 27.11 ± 6.28 | 105.46 ± 23.93 | 8.39 ± 2.26 | 15.80 ± 4.44 | 8.06 ± 2.57 | 13.68 ± 3.46 | 67.61 ± 12.82 | 69.60 ± 15.29 | 62.82 ± 11.62 |

| t | 0.190 | 0.911 | −0.525 | −1.002 | 1.074 | 0.815 | 0.608 | 0.640 | 0.312 |

| p | 0.849 | 0.363 | 0.600 | 0.317 | 0.284 | 0.416 | 0.544 | 0.523 | 0.756 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Han nationality | 27.20 ± 6.08 | 107.93 ± 22.13 | 8.20 ± 2.32 | 15.33 ± 3.98 | 8.34 ± 2.38 | 13.97 ± 3.29 | 68.49 ± 12.19 | 70.70 ± 13.94 | 63.20 ± 12.12 |

| Minority | 29.57 ± 8.79 | 108.00 ± 24.38 | 10.00 ± 2.31 | 14.54 ± 3.22 | 9.71 ± 2.06 | 15.57 ± 3.31 | 69.85 ± 11.24 | 70.98 ± 13.89 | 67.14 ± 9.83 |

| t | −1.012 | −0.008 | −2.032 | 0.518 | −1.513 | −1.272 | −0.293 | −0.054 | −0.853 |

| p | 0.313 | 0.993 | 0.043 * | 0.605 | 0.131 | 0.204 | 0.770 | 0.957 | 0.394 |

| Average monthly income per family member (CNY) | |||||||||

| No data | 26.86 ± 7.17 | 118.92 ± 21.47 | 7.00 ± 2.32 | 13.36 ± 3.69 | 6.57 ± 2.62 | 11.46 ± 4.49 | 69.95 ± 10.95 | 69.79 ± 13.67 | 70.36 ± 8.76 |

| <5000 | 25.71 ± 6.69 | 101.56 ± 24.78 | 8.76 ± 2.30 | 14.99 ± 3.53 | 8.97 ± 2.53 | 13.65 ± 3.23 | 66.07 ± 12.93 | 67.97 ± 15.40 | 61.51 ± 12.23 |

| 5000 to 10,000 | 27.13 ± 5.86 | 108.50 ± 21.23 | 8.35 ± 2.30 | 15.34 ± 3.89 | 8.32 ± 2.18 | 14.09 ± 3.03 | 69.29 ± 11.91 | 71.66 ± 13.62 | 63.62 ± 11.49 |

| 10,001 to 15,000 | 28.26 ± 6.24 | 109.51 ± 21.45 | 7.76 ± 1.91 | 16.01 ± 4.20 | 8.13 ± 2.34 | 14.80 ± 3.30 | 67.74 ± 11.78 | 70.51 ± 12.67 | 61.11 ± 12.83 |

| >15,000 | 29.11 ± 5.18 | 110.16 ± 20.36 | 8.06 ± 2.86 | 15.49 ± 4.58 | 8.60 ± 2.56 | 14.11 ± 3.50 | 70.34 ± 12.67 | 72.29 ± 14.37 | 65.64 ± 13.16 |

| F | 2.218 | 2.389 | 2.533 | 1.399 | 3.326 | 3.167 | 1.089 | 0.910 | 2.381 |

| p | 0.067 | 0.051 | 0.040 * | 0.234 | 0.011 * | 0.014 * | 0.362 | 0.458 | 0.052 |

| Education level | |||||||||

| Junior high school or below | 24.95 ± 6.46 | 103.59 ± 23.62 | 7.74 ± 2.19 | 14.92 ± 3.65 | 8.85 ± 2.46 | 13.56 ± 3.55 | 67.44 ± 12.56 | 68.40 ± 14.45 | 65.13 ± 10.97 |

| High school | 26.48 ± 5.98 | 106.19 ± 22.10 | 8.57 ± 2.45 | 15.33 ± 4.06 | 8.62 ± 2.47 | 13.78 ± 3.44 | 67.96 ± 11.46 | 69.45 ± 14.03 | 64.38 ± 11.91 |

| College or university | 27.32 ± 6.02 | 108.54 ± 22.45 | 8.28 ± 2.24 | 15.17 ± 3.63 | 8.33 ± 2.20 | 14.12 ± 3.10 | 68.91 ± 12.38 | 71.46 ± 14.02 | 62.80 ± 11.69 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 29.84 ± 5.67 | 111.23 ± 19.83 | 8.22 ± 2.54 | 16.48 ± 4.99 | 8.05 ± 2.74 | 14.59 ± 3.44 | 68.65 ± 12.10 | 71.52 ± 12.85 | 61.76 ± 14.43 |

| F | 4.965 | 0.990 | 1.025 | 1.465 | 1.007 | 0.847 | 0.205 | 0.739 | 0.797 |

| p | 0.002 * | 0.398 | 0.382 | 0.224 | 0.390 | 0.469 | 0.893 | 0.529 | 0.496 |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Employed | 25.85 ± 6.02 | 102.59 ± 22.71 | 8.59 ± 2.24 | 15.90 ± 3.36 | 8.95 ± 2.28 | 13.90 ± 3.27 | 66.11 ± 12.65 | 67.23 ± 15.05 | 63.40 ± 11.98 |

| Unemployed | 27.72 ± 6.16 | 109.16 ± 22.05 | 8.16 ± 2.37 | 15.17 ± 4.16 | 8.26 ± 2.35 | 14.03 ± 3.34 | 68.99 ± 11.95 | 71.42 ± 13.48 | 63.15 ± 12.18 |

| t | −2.174 | −2.108 | 1.299 | 1.282 | 2.106 | −0.290 | −1.689 | −2.147 | 0.142 |

| p | 0.030 * | 0.036 * | 0.195 | 0.201 | 0.036 * | 0.772 | 0.092 | 0.033 * | 0.887 |

| Number of children | |||||||||

| 0 | 27.31 ± 6.16 | 107.60 ± 22.44 | 8.24 ± 2.38 | 15.40 ± 4.01 | 8.37 ± 2.34 | 14.11 ± 3.27 | 68.03 ± 12.42 | 70.13 ± 14.17 | 62.99 ± 12.36 |

| 1 | 26.63 ± 5.80 | 109.63 ± 20.36 | 8.26 ± 2.08 | 14.89 ± 3.46 | 8.59 ± 2.40 | 13.65 ± 3.34 | 70.88 ± 11.03 | 73.44 ± 12.60 | 64.73 ± 10.71 |

| 2 | 29.75 ± 7.38 | 112.00 ± 23.63 | 8.43 ± 2.64 | 15.57 ± 5.44 | 7.43 ± 3.55 | 13.21 ± 4.00 | 70.69 ± 8.91 | 72.02 ± 12.30 | 67.50 ± 7.64 |

| F | 0.906 | 0.295 | 0.024 | 0.335 | 0.736 | 0.590 | 1.183 | 1.135 | 0.829 |

| p | 0.405 | 0.745 | 0.976 | 0.715 | 0.480 | 0.555 | 0.308 | 0.323 | 0.438 |

| Type of infertility | |||||||||

| Primary | 27.29 ± 6.10 | 109.60 ± 22.57 | 8.17 ± 2.22 | 15.39 ± 3.81 | 8.44 ± 2.28 | 14.12 ± 3.07 | 68.90 ± 12.06 | 71.34 ± 13.25 | 63.04 ± 13.02 |

| Secondary | 27.18 ± 6.19 | 105.89 ± 21.52 | 8.37 ± 2.46 | 15.29 ± 4.13 | 8.33 ± 2.50 | 13.91 ± 3.58 | 67.83 ± 12.25 | 69.56 ± 14.67 | 63.67 ± 10.65 |

| t | 0.153 | 1.464 | −0.751 | 0.231 | 0.393 | 0.542 | 0.767 | 1.117 | −0.455 |

| p | 0.878 | 0.144 | 0.453 | 0.817 | 0.695 | 0.588 | 0.444 | 0.265 | 0.650 |

| Duration of infertility diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| <1 | 26.78 ± 5.98 | 107.64 ± 22.67 | 8.50 ± 2.17 | 14.94 ± 3.55 | 8.02 ± 2.35 | 14.12 ± 3.19 | 68.03 ± 8.13 | 72.33 ± 12.25 | 63.84 ± 12.32 |

| 1 to 2 | 27.62 ± 7.05 | 110.68 ± 21.95 | 8.72 ± 2.50 | 15.30 ± 4.02 | 8.88 ± 2.19 | 14.39 ± 3.51 | 69.98 ± 9.10 | 72.62 ± 12.88 | 63.63 ± 12.08 |

| >2 | 30.47 ± 5.52 | 109.28 ± 20.37 | 8.93 ± 2.34 | 15.60 ± 4.10 | 9.27 ± 4.08 | 14.56 ± 3.51 | 72.35 ± 8.42 | 70.28 ± 13.26 | 65.76 ± 14.87 |

| F | 3.039 | 1.521 | 2.608 | 2.221 | 1.429 | 0.311 | 2.680 | 2.067 | 1.462 |

| p | 0.016 * | 0.220 | 0.075 | 0.110 | 0.271 | 0.281 | 0.037 * | 0.048 * | 0.087 |

| Duration of fertility treatments (years) | |||||||||

| < 1 | 27.69 ± 6.03 | 107.28 ± 22.45 | 8.26 ± 2.53 | 16.23 ± 4.58 | 8.28 ± 2.52 | 14.12 ± 3.80 | 69.36 ± 11.53 | 72.02 ± 12.87 | 64.36 ± 11.86 |

| 1 to 2 | 25.69 ± 6.96 | 109.72 ± 19.30 | 8.45 ± 1.99 | 16.25 ± 4.33 | 8.54 ± 2.59 | 14.22 ± 3.82 | 68.48 ± 11.15 | 70.51 ± 12.36 | 60.90 ± 12.97 |

| >2 | 27.93 ± 4.03 | 110.05 ± 21.22 | 8.57 ± 2.57 | 16.92 ± 4.56 | 8.77 ± 2.85 | 14.38 ± 3.77 | 64.73 ± 11.33 | 66.65 ± 13.98 | 63.01 ± 12.06 |

| F | 2.714 | 1.625 | 1.357 | 2.400 | 2.673 | 0.378 | 14.768 | 14.059 | 6.305 |

| p | 0.037 * | 0.197 | 0.258 | 0.091 | 0.069 | 0.687 | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.002 * |

| Embryo transfer cycle | |||||||||

| 0 | 27.65 ± 6.11 | 108.91 ± 22.04 | 8.03 ± 2.36 | 15.04 ± 3.87 | 8.06 ± 2.33 | 13.79 ± 3.25 | 70.16 ± 10.78 | 72.80 ± 12.19 | 63.84 ± 11.46 |

| 1 | 26.58 ± 6.38 | 107.56 ± 22.71 | 8.53 ± 2.38 | 15.55 ± 4.21 | 8.86 ± 2.34 | 14.64 ± 3.23 | 67.25 ± 14.09 | 68.33 ± 16.21 | 64.67 ± 12.87 |

| 2 | 26.13 ± 5.99 | 102.17 ± 21.72 | 8.13 ± 2.14 | 14.87 ± 3.91 | 8.39 ± 2.73 | 13.00 ± 3.67 | 66.14 ± 12.01 | 68.75 ± 13.70 | 59.89 ± 13.74 |

| 3 | 28.90 ± 5.43 | 105.70 ± 18.20 | 9.40 ± 1.07 | 16.90 ± 3.11 | 9.50 ± 2.22 | 15.50 ± 2.17 | 61.32 ± 13.31 | 63.33 ± 16.07 | 56.50 ± 10.22 |

| >3 | 24.88 ± 5.36 | 106.75 ± 27.30 | 9.50 ± 2.20 | 19.00 ± 3.02 | 9.88 ± 1.81 | 14.38 ± 4.14 | 56.25 ± 13.54 | 56.77 ± 16.16 | 55.00 ± 11.34 |

| F | 1.111 | 0.517 | 1.935 | 2.566 | 3.052 | 2.014 | 4.421 | 4.695 | 2.589 |

| p | 0.351 | 0.723 | 0.104 | 0.038 | 0.017 | 0.092 | 0.002 * | 0.001 * | 0.037 * |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resilience | 1 | ||||||

| 2 ISE | 0.509 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3.1 Active-avoidance | −0.038 | −0.215 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3.2 Active-confronting | 0.135 * | 0.052 | 0.400 ** | 1 | |||

| 3.3 Passive-avoidance | −0.013 | −0.096 | 0.375 ** | 0.503 ** | 1 | ||

| 3.4 Meaning-based | 0.283 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.510 ** | 1 | |

| 4 FertiQoL | 0.375 ** | 0.584 ** | −0.367 ** | −0.143 * | −0.130 * | 0.191 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1 FertiQoL | Model 2 ISE | Model 3 Active-Confronting Coping | Model 4 Meaning-Based Coping | Model 5 FertiQoL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Employment | 0.095 | 0.755 | 0.1351 | 1.0865 | −0.227 | −1.599 | −0.047 | −0.342 | −0.009 | −0.088 |

| Duration of infertility diagnosis | 0.169 | 2.419 * | 0.0763 | 1.0991 | −0.027 | −0.336 | 0.030 | 0.385 | 0.123 | 2.070 ** |

| Duration of fertility treatments | −0.322 | −4.121 | −0.0366 | −0.4723 | 0.141 | 1.599 | 0.050 | 0.586 | −0.283 | −4.246 *** |

| Embryo transfer cycle | −0.138 | −2.351 *** | −0.0294 | −0.504 | 0.122 | 1.834 | 0.058 | 0.896 | −0.108 | −2.147 ** |

| Resilience | 0.368 | 7.046 *** | 0.532 | 10.256 *** | 0.189 | 3.202 ** | 0.339 | 5.921 *** | 0.105 | 1.981 * |

| ISE | 0.467 | 9.079 *** | ||||||||

| Active-confronting coping | −0.214 | −4.137 *** | ||||||||

| Meaning-based coping | 0.161 | 2.985 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.247 | 0.285 | 0.072 | 0.115 | 0.463 | |||||

| F | 18.826 *** | 22.665 *** | 4.432 *** | 7.401 *** | 30.375 *** | |||||

| Type of Effect | Value | Boot SE | Boot 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Total effect | 0.368 | 0.052 | 0.272 | 0.476 |

| Direct effect | 0.105 | 0.055 | −0.002 | 0.215 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Total | 0.263 | 0.042 | 0.188 | 0.350 |

| ISE | 0.248 | 0.039 | 0.178 | 0.331 |

| Active-confronting coping | −0.040 | 0.017 | −0.078 | −0.012 |

| Meaning-based coping | 0.055 | 0.023 | 0.014 | 0.104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhouchen, Y.-B.; Luo, Y.; Wang, S.-Y.; Redding, S.R.; Ouyang, Y.-Q.; Fu, D. Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility Quality of Life in Infertile Women: Mediating Roles of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2589. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202589

Xu J, Zhang X-Y, Zhouchen Y-B, Luo Y, Wang S-Y, Redding SR, Ouyang Y-Q, Fu D. Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility Quality of Life in Infertile Women: Mediating Roles of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2589. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202589

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jing, Xin-Yuan Zhang, Yi-Bei Zhouchen, Ying Luo, Shi-Yun Wang, Sharon R. Redding, Yan-Qiong Ouyang, and Dou Fu. 2025. "Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility Quality of Life in Infertile Women: Mediating Roles of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2589. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202589

APA StyleXu, J., Zhang, X.-Y., Zhouchen, Y.-B., Luo, Y., Wang, S.-Y., Redding, S. R., Ouyang, Y.-Q., & Fu, D. (2025). Relationship Between Resilience and Fertility Quality of Life in Infertile Women: Mediating Roles of Infertility Self-Efficacy and Infertility Coping. Healthcare, 13(20), 2589. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202589