Scenario-Based Ethical Reasoning Among Healthcare Trainees and Practitioners: Evidence from Dental and Medical Cohorts in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Instrumentation

- –

- Informed consent and transparency: “If a patient’s family requests that you withhold the diagnosis of cancer, would you comply?” (Yes/No/It depends).

- –

- Confidentiality and mandatory reporting: “If you suspect child abuse but lack definitive proof, are you obliged to report this case?”

- –

- Medical error and professional responsibility: “If you make a medical error that does not cause harm, should you disclose it to the patient?”

- –

- End-of-life care and resource allocation: “In a situation of scarce resources, should younger patients be given priority over older ones?”

- –

- Conflicts of interest: “Would you accept a non-monetary benefit (e.g., a gift or trip) from a pharmaceutical representative?”

- –

- Moral and cultural norms: “Would a romantic or sexual relationship with a current patient be acceptable under certain circumstances?”

- –

- Ethics in exceptional circumstances: “If protective equipment is insufficient, is it ethically justifiable to abandon care for infectious patients?”

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Approval and Consent

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Overall Response Patterns to Ethical Dilemmas

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Ethical Domains

3.3.1. Informed Consent and Transparency

3.3.2. Confidentiality and Mandatory Reporting

3.3.3. Medical Error and Professional Responsibility

3.3.4. Preventive Duties and Vaccination

3.3.5. End-of-Life Decisions and Resource Allocation

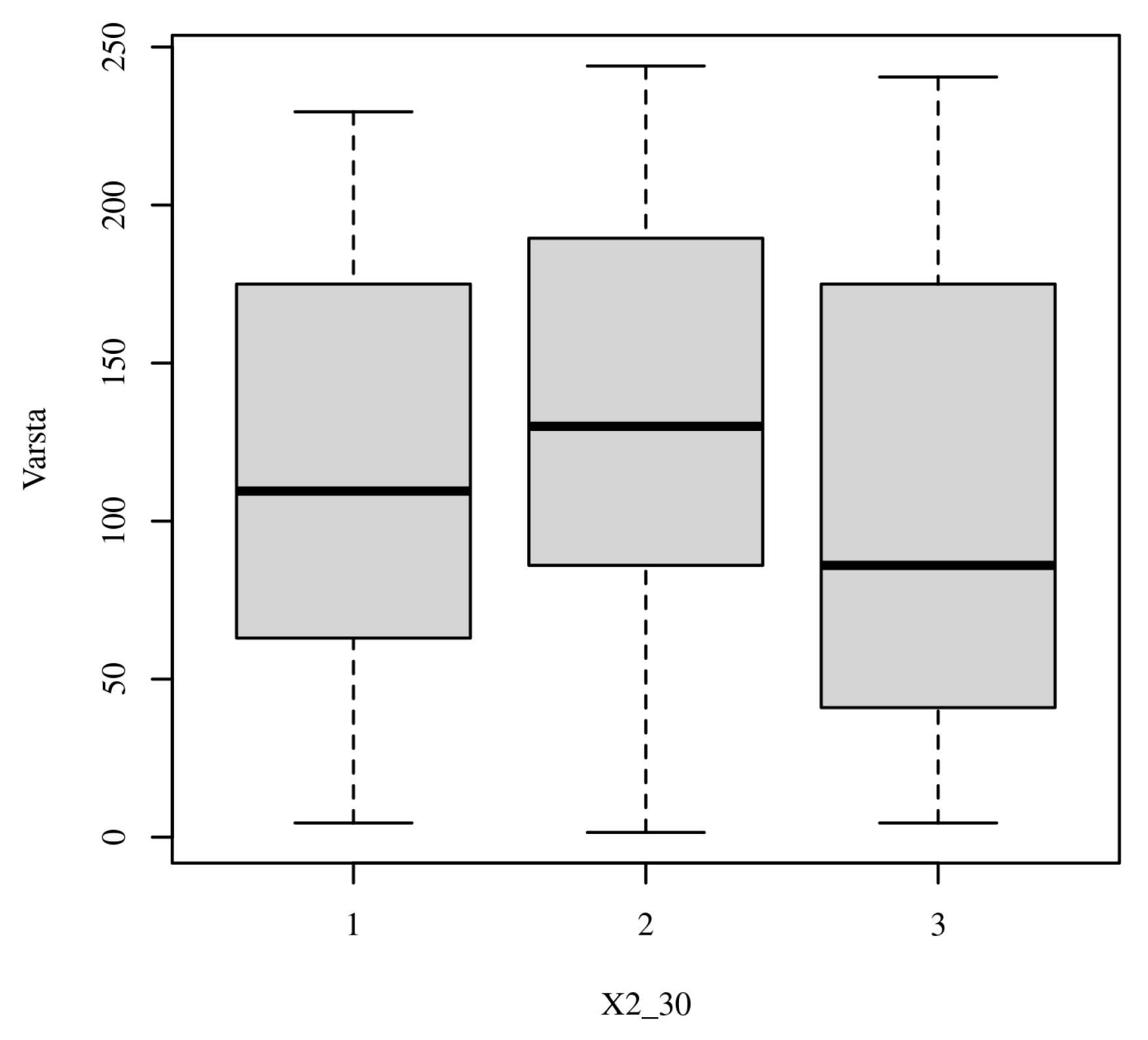

3.3.6. Conflicts of Interest

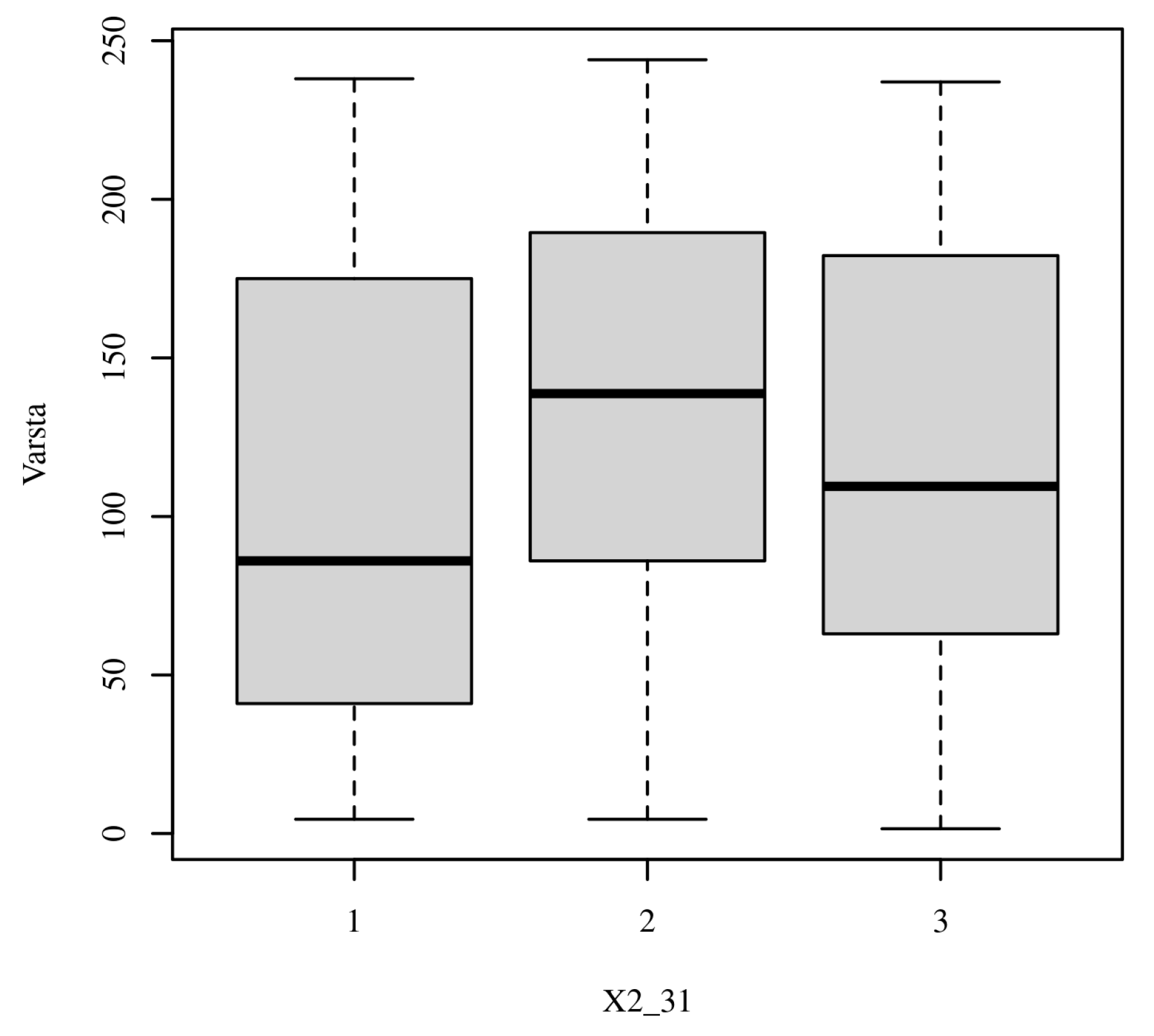

3.3.7. Moral and Cultural Norms

3.3.8. Ethics in Exceptional Circumstances (Crisis Situations)

3.4. Summary of Consensus and Divergence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| WMA | World Medical Association |

| χ2 | Chi-square |

References

- Varkey, B. Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice. Med. Princ. Pract. 2021, 30, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.; Childress, J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics: Marking Its Fortieth Anniversary. Am. J. Bioeth. 2019, 19, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, S.; Kanekar, A. Ethical Issues Surrounding End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akdeniz, M.; Yardımcı, B.; Kavukcu, E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211000918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koesel, N.; Link, M. Conflicts in goals of care at the end of life: Are aggressive life-prolonging interventions and a “Good Death” compatible? J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2014, 16, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, O.; Kolawole, T.; Olaboye, J. Ethical Dilemmas in Healthcare Management: A Comprehensive Review. Int. Med. Sci. Res. J. 2024, 4, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.; Żok, A.; Baum, E. Ethical principles across countries: Does ‘ethical’ mean the same everywhere? Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1579778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bauer, D.; Orchard, D.A.; Day, P.G.; Tunzi, M.; Satin, D.J. A literature review of non-financial conflicts of interest in healthcare research and publication. BMC Med. Ethics 2025, 26, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanu, C.A.; Plaiasu, M.C.; Edu, A. Geographic and Specialty-Specific Disparities in Physicians’ Legal Compliance: A National-Scale Assessment of Romanian Medical Practice. Healthcare 2023, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.D.; Papanikitas, A.N.; Spicer, J. Medical ethics education as translational bioethics. Bioethics 2024, 38, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, G.-D.; Mazilescu, C.-A.; Hoinoiu, T.; Hoinoiu, B.; Luca, R.E.; Viscu, L.-I.; Pasca, I.G.; Oancea, R. Attitude of Romanian Medical Students and Doctors toward Business Ethics: Analyzing the Influence of Sex, Age, and Ethics Education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1452–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, E.B.; Dankwa-Mullan, I.; Nelson, W.A.; Hassanpour, S. Ethical challenges and evolving strategies in the integration of artificial intelligence into clinical practice. PLoS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanduni Nishara, M.G.; Ariyasinghe Asurakkody, T. Ethical challenges experienced by nurses during COVID-19: Are we ready for tomorrow? BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suciu, Ş.M.; Popescu, C.A.; Ciumageanu, M.D.; Buzoianu, A.D. Physician migration at its roots: A study on the emigration preferences and plans among medical students in Romania. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillon, R. Medical ethics: Four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ 1994, 309, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, R.; Valizadeh, L.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Hassankhani, H.; Jafarzadeh, A. Clarification of ethical principle of the beneficence in nursing care: An integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.A.; Shaban, M.M.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Zaky, M.E.; Mohammed, H.H.; Amer, F.G.M.; Shaban, M. Navigating end-of-life decision-making in nursing: A systematic review of ethical challenges and palliative care practices. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, K.; Chen, J. Conflict Resolution in End of Life Treatment Decisions: An Evidence Check Rapid Review Brokered by the Sax Institute (http://www.saxinstitute.org.au) for the Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health; The Sax Institute: Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Plaiasu, M.C.; Alexandru, D.O.; Nanu, C.A. Patients’ rights in physicians’ practice during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Romania. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisz, D.; Crișan, I.; Reisz, A.; Tudor, R.; Georgescu, D. Stress and Bio-Ethical Issues Perceived by Romanian Healthcare Practitioners in the COVID-19 Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieb, K.; Koch, C. Medical students’ attitudes to and contact with the pharmaceutical industry: A survey at eight German university hospitals. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2013, 110, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaldjian, L.C.; Jones, E.W.; Wu, B.J.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Levi, B.H.; Rosenthal, G.E. Disclosing medical errors to patients: Attitudes and practices of physicians and trainees. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- White, A.A.; Gallagher, T.H.; Krauss, M.J.; Garbutt, J.; Waterman, A.D.; Dunagan, W.C.; Fraser, V.J.; Levinson, W.; Larson, E.B. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad. Med. 2008, 83, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbutt, J.; Brownstein, D.R.; Klein, E.J.; Waterman, A.; Krauss, M.J.; Marcuse, E.K.; Hazel, E.; Dunagan, W.C.; Fraser, V.; Gallagher, T.H. Reporting and disclosing medical errors: Pediatricians’ attitudes and behaviors. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazor, K.M.; Simon, S.R.; Gurwitz, J.H. Communicating with patients about medical errors: A review of the literature. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwer, L.A.; Abu-Zaid, A. Transparency in medical error disclosure: The need for formal teaching in undergraduate medical education curriculum. Med. Educ. Online 2012, 19, 23542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montori, V.M.; Ruissen, M.M.; Hargraves, I.G.; Brito, J.P.; Kunneman, M. Shared decision-making as a method of care. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kachalia, A. Improving patient safety through transparency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1677–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, Z.R.; Hughes, R.G. Error Reporting and Disclosure. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008; Chapter 35. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2652/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Landrigan, C.P.; Rahman, S.A.; Sullivan, J.P.; Vittinghoff, E.; Barger, L.K.; Sanderson, A.L.; Wright KPJr O’Brien, C.S.; Qadri, S.; St Hilaire, M.A.; Halbower, A.C.; et al. Effect on Patient Safety of a Resident Physician Schedule without 24-Hour Shifts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2514–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sukalich, S.; Elliott, J.O.; Ruffner, G. Teaching medical error disclosure to residents using patient-centered simulation training. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulchinsky, T.H. Ethical Issues in Public Health. Case Stud. Public Health 2018, 277–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Janati, A.; Hosseiny, M.; Gouya, M.M.; Moradi, G.; Ghaderi, E. Communicable Disease Reporting Systems in the World: A Systematic Review Article. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krause, G.; Ropers, G.; Stark, K. Notifiable disease surveillance and practicing clinicians. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berthold, O.; Clemens, V.; Levi, B.H.; Jarczok, M.; Fegert, J.M.; Jud, A. Survey on Reporting of Child Abuse by Pediatricians: Intrapersonal Inconsistencies Influence Reporting Behavior More than Legislation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghalandarpoorattar, S.M.; Kaviani, A.; Asghari, F. Medical error disclosure: The gap between attitude and practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 2012, 88, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, T.H.; Waterman, A.D.; Ebers, A.G.; Fraser, V.J.; Levinson, W. Patients’ and Physicians’ Attitudes Regarding the Disclosure of Medical Errors. JAMA 2003, 289, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaiasu, M.C.; Alexandru, D.O.; Nanu, C.A. Physicians’ legal knowledge of informed consent and confidentiality. A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronegger, W.J.; Schmölzer, C.; Rásky, E.; Freidl, W. Changing attitudes towards euthanasia among medical students in Austria. J. Med. Ethics 2011, 37, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.E.; Klein, E.; Jaspers, B.; Klaschik, E. Attitudes toward active euthanasia among medical students at two German universities. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, J.; Van Den Branden, S.; Broeckaert, B. Attitudes of European physicians toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A review of the recent literature. J. Palliat. Care 2008, 24, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg, A.; Evenblij, K.; Pasman, H.R.W.; van Delden, J.J.M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; van der Heide, A. Physicians’ and Public Attitudes Toward Euthanasia in People with Advanced Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2319–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Willems, D.L.; Daniels, E.R.; van der Wal, G.; van der Maas, P.J.; Emanuel, E.J. Attitudes and practices concerning the end of life: A comparison between physicians from the United States and from The Netherlands. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E.G.; Gruen, R.L.; Mountford, J.; Miller, L.G.; Cleary, P.D.; Blumenthal, D. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnke, K.; Kremer, M.S.; Schmidt, C.O.; Kochen, M.M.; Chenot, J.F. German medical students’ exposure and attitudes toward pharmaceutical promotion: A cross-sectional survey. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2014, 31, Doc32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Ferrari, A.; Gentille, C.; Davalos, L.; Huayanay, L.; Malaga, G. Attitudes and relationship between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry in a public general hospital in Lima, Peru. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fickweiler, F.; Fickweiler, W.; Urbach, E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gabbard, G.O.; Nadelson, C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 1995, 273, 1445–1449, Erratum in JAMA 1995, 274, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. Crossing the line: Sexual boundary violations by physicians. Psychiatry 2009, 6, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parsa-Parsi, R.W. The International Code of Medical Ethics of the World Medical Association. JAMA 2022, 328, 2018–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, E.J.; Persad, G.; Upshur, R.; Thome, B.; Parker, M.; Glickman, A.; Zhang, C.; Boyle, C.; Smith, M.; Phillips, J.P. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savulescu, J.; Cameron, J.; Wilkinson, D. Equality or utility? Ethics and law of rationing ventilators. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.A.; King, A.M.; D’Addario, A.E.; Brigham, K.B.; Bradley, J.M.; Gallagher, T.H.; Mazor, K.M. Crowdsourced Feedback to Improve Resident Physician Error Disclosure Skills: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2425923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meier, L.J. Systemising triage: COVID-19 guidelines and their underlying theories of distributive justice. Med. Health Care Philos. 2022, 25, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Aldasoro, E.; O’Brien, Á.; Nolan, M.; McGovern, C.; Carroll, Á. Ethical values and principles to guide the fair allocation of resources in response to a pandemic: A rapid systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goulet, F.; Hudon, E.; Gagnon, R.; Gauvin, E.; Lemire, F.; Arsenault, I. Effects of continuing professional development on clinical performance: Results of a study involving family practitioners in Quebec. Can. Fam. Physician 2013, 59, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spickard, W.A., Jr.; Swiggart, W.H.; Manley, G.T.; Samenow, C.P.; Dodd, D.T. A continuing medical education approach to improve sexual boundaries of physicians. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2008, 72, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozar, D.T.; Sokol, D.J.; Patthoff, D.E. Dental Ethics at Chairside: Professional Obligations and Practical Applications, 3rd ed.; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Students (n = 51) | Physicians (n = 193) | Total (n = 244) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender—male, n (%) | 8 (15.69) | 46 (23.83) | 54 (22.13) |

| Gender—female, n (%) | 43 (84.31) | 147 (76.17) | 190 (77.87) |

| Specialization—Dentistry, n (%) | 42 (82.35) | 132 (68.39) | 174 (71.31) |

| Specialization—General Medicine, n (%) | 9 (17.65) | 61 (31.61) | 70 (28.69) |

| Median years of experience (IQR) | - | 12 (6–21) | - |

| Response Option | Students (%) | Physicians (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 35.6 | 32.9 | 33.5 |

| No | 16.7 | 19.4 | 18.7 |

| It Depends | 47.7 | 47.7 | 47.8 |

| Item | Scenario | Students: Yes (%) | Students: No (%) | Students: It Depends (%) | Physicians: Yes (%) | Physicians: No (%) | Physicians: It Depends (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 3 | Withhold diagnosis on family request | 15.69 | 58.82 | 25.49 | 22.8 | 41.45 | 35.75 | 0.085 |

| Item 4 | Hide medical error (no harm) | 23.53 | 56.86 | 19.61 | 21.76 | 52.33 | 25.91 | 0.649 |

| Item 5 | Hide medical error (with harm) | 1.96 | 94.12 | 3.92 | 5.18 | 87.56 | 7.25 | 0.405 |

| Item 20 | Higher insurance for unhealthy lifestyle | 23.53 | 49.02 | 27.45 | 48.7 | 37.31 | 13.99 | 0.003 |

| Item 21 | Treat families refusing vaccines | 78.43 | 5.88 | 15.69 | 75.13 | 12.44 | 12.44 | 0.377 |

| Item 22 | Annual influenza vaccine for clinicians | 52.94 | 29.41 | 17.65 | 32.64 | 40.93 | 26.42 | 0.028 |

| Item 24 | Authorize purchase of organs (RO) | 76.47 | 5.88 | 17.65 | 62.18 | 20.73 | 17.1 | 0.043 |

| Item 26 | Prioritize younger patients (scarcity) | 35.29 | 23.53 | 41.18 | 33.68 | 24.35 | 41.97 | 0.145 |

| Item 34 | Abandon care if PPE insufficient | 43.14 | 33.33 | 23.53 | 35.23 | 40.93 | 23.83 | 0.528 |

| Item 35 | Abandon care if no treatments available | 21.57 | 58.82 | 19.61 | 19.17 | 55.44 | 25.39 | 0.685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Constantin, G.-D.; Hoinoiu, B.; Veja, I.; Lile, I.E.; Mazilescu, C.-A.; Luca, R.E.; Munteanu, I.R.; Oancea, R. Scenario-Based Ethical Reasoning Among Healthcare Trainees and Practitioners: Evidence from Dental and Medical Cohorts in Romania. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202583

Constantin G-D, Hoinoiu B, Veja I, Lile IE, Mazilescu C-A, Luca RE, Munteanu IR, Oancea R. Scenario-Based Ethical Reasoning Among Healthcare Trainees and Practitioners: Evidence from Dental and Medical Cohorts in Romania. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202583

Chicago/Turabian StyleConstantin, George-Dumitru, Bogdan Hoinoiu, Ioana Veja, Ioana Elena Lile, Crisanta-Alina Mazilescu, Ruxandra Elena Luca, Ioana Roxana Munteanu, and Roxana Oancea. 2025. "Scenario-Based Ethical Reasoning Among Healthcare Trainees and Practitioners: Evidence from Dental and Medical Cohorts in Romania" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202583

APA StyleConstantin, G.-D., Hoinoiu, B., Veja, I., Lile, I. E., Mazilescu, C.-A., Luca, R. E., Munteanu, I. R., & Oancea, R. (2025). Scenario-Based Ethical Reasoning Among Healthcare Trainees and Practitioners: Evidence from Dental and Medical Cohorts in Romania. Healthcare, 13(20), 2583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202583