Enteroenteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in an Adult: Case Report, Literature Review and Management Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient Information

2.2. Presenting Concerns

2.3. Clinical Findings

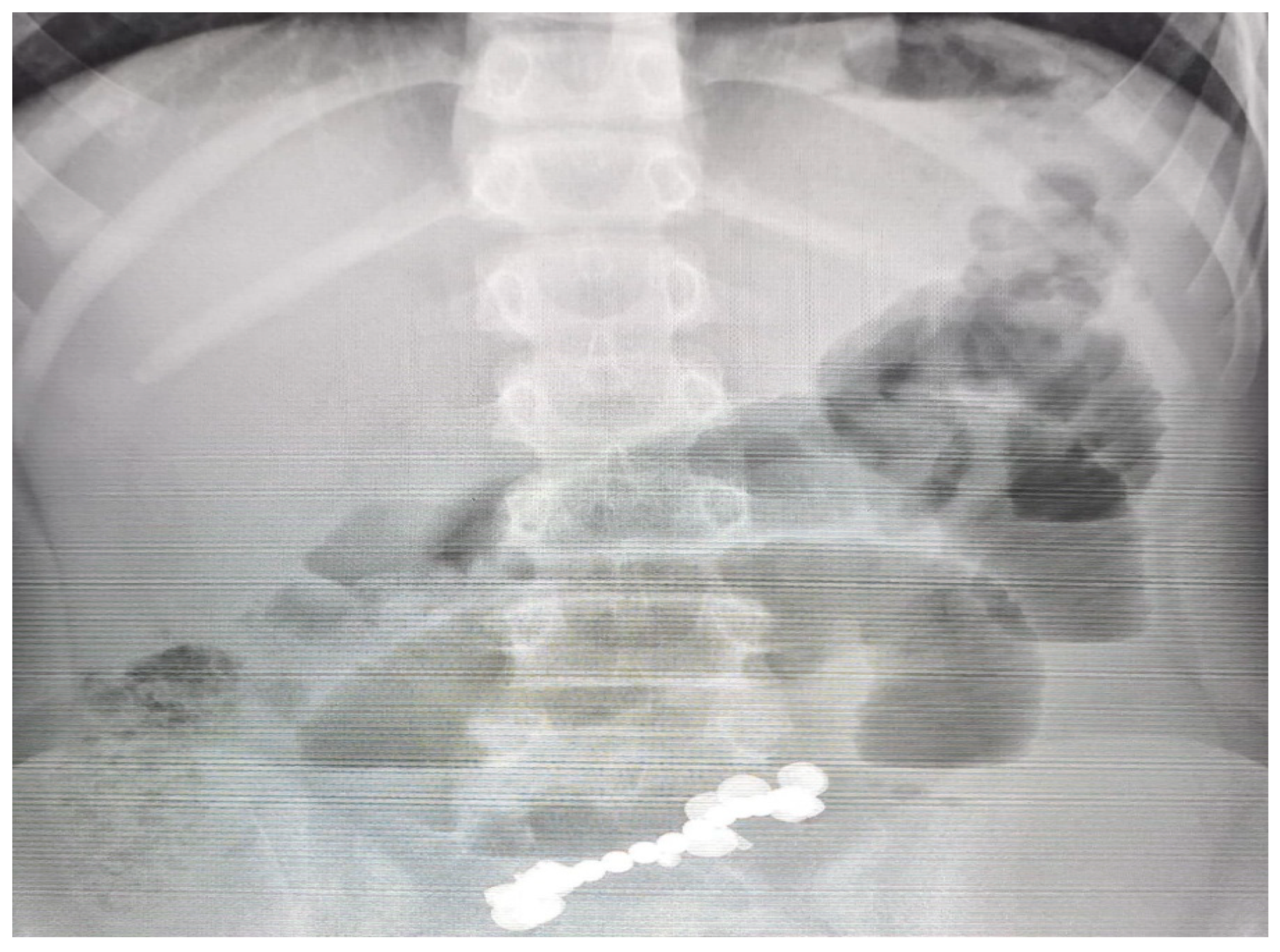

2.4. Diagnostic Assessment

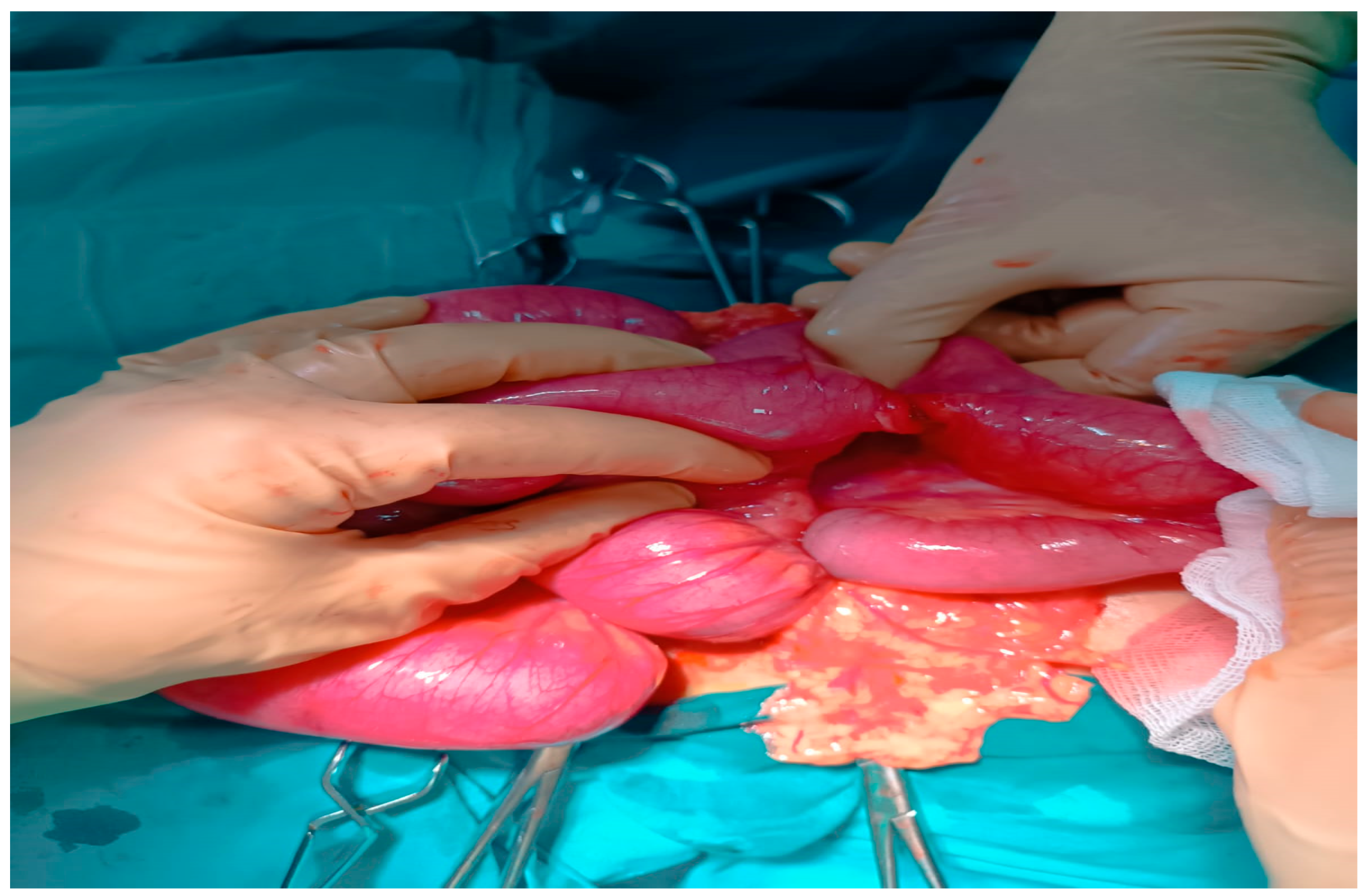

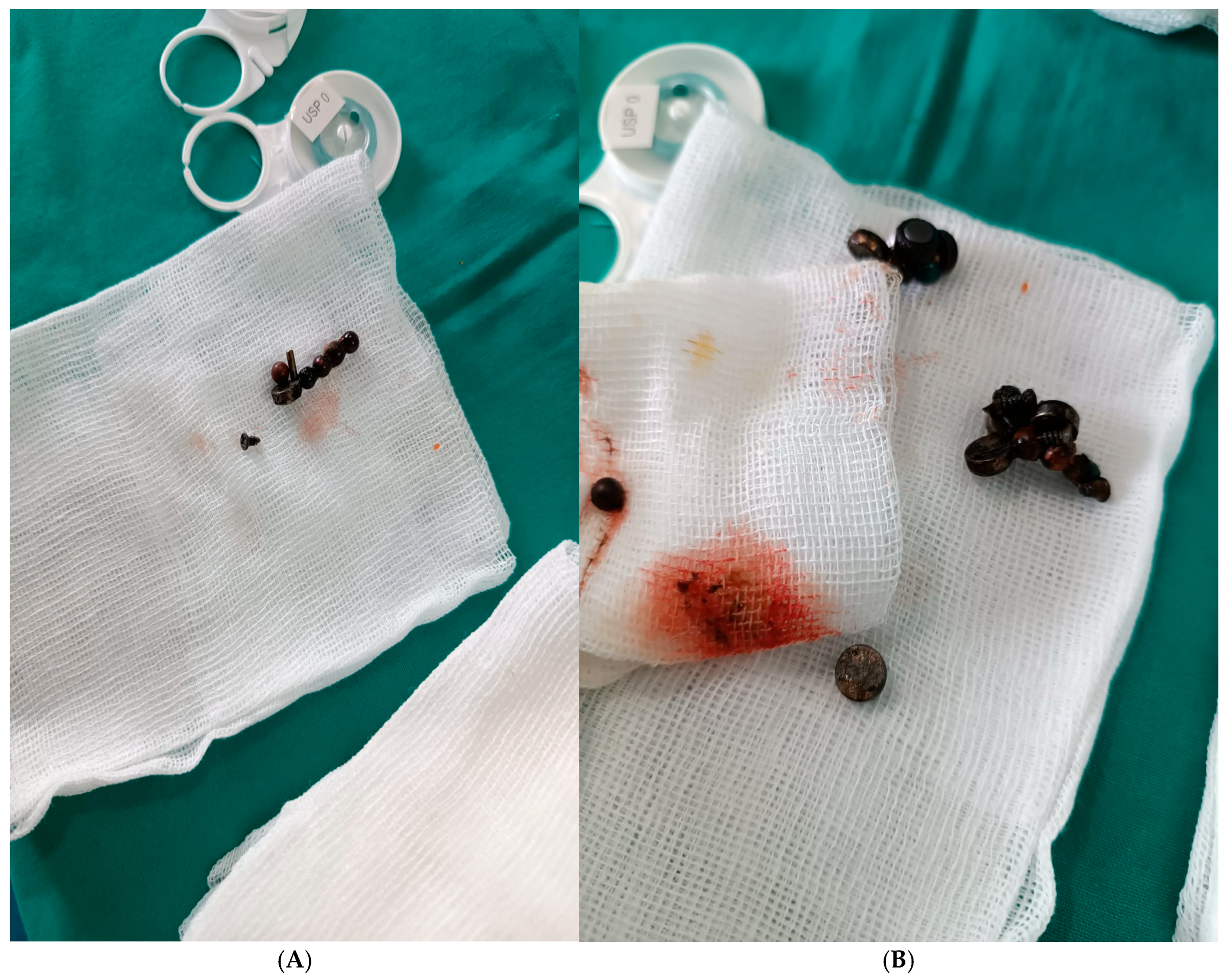

2.5. Therapeutic Intervention

2.6. Postoperative Course and Follow-Up

2.7. Patient Perspective

2.8. Informed Consent

2.9. Timeline of Clinical Events

2.10. Literature Review Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Relevance

3.2. Pediatric vs. Adult Prevalence

3.3. Time to Complications

3.4. Fistula Types Reported

3.5. Pathophysiological Mechanisms

3.6. Role of Early Diagnosis and Rapid Intervention

3.7. Comparative Clinical, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Features in Pediatric Versus Adult Magnet Ingestion

3.7.1. Clinical Presentation

3.7.2. Diagnosis

3.7.3. Treatment and Outcomes

3.8. Psychiatric Implications of Magnet Ingestion in Adults

3.9. Limitations in Reported Adult Cases

3.10. Implications for Clinical Practice

3.11. Proposed Adult Management Algorithm for Multiple Magnet Ingestion

- Step 1—Initial Assessment

- Step 2—Risk Stratification

- Single magnet, asymptomatic: observation with serial radiographs ≤ 24 h to confirm progression.

- Step 3—Intervention

- Magnets in stomach or accessible duodenum: urgent endoscopic removal within 12 h.

- Distal magnets, asymptomatic, with documented progression: inpatient observation, nil per os, clinical monitoring, and abdominal radiographs every 8–12 h; surgical exploration is indicated for peritonitis signs or lack of progression [28].

- Distal magnets with symptoms, stagnation, or perforation signs: laparotomy or laparoscopy with resection if required [4].

- Step 4—Post-Intervention

- All intentional ingestion cases should undergo postoperative monitoring and psychiatric evaluation.

3.12. Comparison with Reported Cases in the Literature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alansari, A.N.; Baykuziyev, T.; Soyer, T.; Akıncı, S.M.; Al Ali, K.K.; Aljneibi, A.; Alyasi, N.H.; Afzal, M.; Ksia, A. Magnet ingestion in growing children: A multi-center observational study on single and multiple magnet incidents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Shaul, D.B.; Sydorak, R.M.; Lau, S.T.; Akmal, Y.; Rodriguez, K. Ingestion of magnetic toys: Report of serious complications requiring surgical intervention and a proposed management algorithm. Perm. J. 2013, 17, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevrakis, E.; Raissaki, M.; Xenaki, S.; Astyrakaki, E.; Kholcheva, N.; Chrysos, E. Multiple magnet ingestion causing instestinal obstruction and entero-enteric fistula: Which imaging modality besides radiographs? A case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2018, 31, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doklestić, K.; Lončar, Z.; Jovanović, B.; Veličković, J. Magnets ingestion as a rare cause of ileus in adults: A case report. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2017, 74, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R.; Bachkaniwala, V.; Tadkalkar, V.; Gandhi, C.; Rajput, S. Endoscopic management of magnet ingestion and its adverse events in children. VideoGIE 2022, 7, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, R.; Hakalmaz, A.E.; Kalyoncu Uçar, A.; Beser, O.; Emre, S. Chronic jejuno-colonic fistula and intestinal malabsorption due to multiple magnet ingestions: A case report and systematic review. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2024, 30, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Calello, D.P.; Ruck, B.; Loughran, D.E.; Greller, H.A.; Meaden, C.W. Management patterns of multiple magnet ingestion reported to New Jersey Poison Information and Education System. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugud, A.A.; Tzivinikos, C.; Assa, A.; Borrelli, O.; Broekaert, I.; Martin-de-Carpi, J.; Deganello Saccomani, M.; Dolinsek, J.; Homan, M.; Mas, E.; et al. Gastrointestinal Committee of ESPGHAN. Pediatric Magnet Ingestion, Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention: A European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Position Paper. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 76, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.W.; Liu, S.M.; Huang, K.H.; Chen, Z.M. Surgical treatment of multiple magnet ingestion by children: A single-center experience from China. Qatar Med. J. 2024, 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeloa Miranda, A.; Samson, F.; Andina Martínez, D.; Ruiz Domínguez, J.A.; Sáinz de la Maza, V.T.; Azcúnaga Sanibañez, B.; Cadenas Benítez, M.N.; Díaz Simal, L.; Lobato Salinas, Z.; Gilabert Iriondo, N.; et al. Grupo Ingesta Imanes RiSEUP SPERG. Multicentre study of magnet ingestion in Spanish paediatric emergency departments. An. Pediatr. 2022, 97, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Jeelani, S.M.; Salim, A.; Hussain, B.D. Multiple Magnet Ingestion leading to Bowel Perforation: A Relatively Sinister Foreign Body. Cureus 2019, 11, e5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, K.; Panagidis, A.; Georgiou, G.; Alexopoulos, V.; Sinopidis, X. Double Jejunoileal Fistula after Ingestion of Magnets. J. Indian. Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 24, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaysadan, V.; Perez, M.; Kuo, D. Revisiting swallowed troubles: Intestinal complications caused by two magnets--a case report, review and proposed revision to the algorithm for the management of foreign body ingestion. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2006, 19, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.E.; Lerner, D.G.; Lin, T.; Manfredi, M.; Shah, M.; Stephen, T.C.; Gibbons, T.E.; Pall, H.; Sahn, B.; McOmber, M.; et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Endoscopy Committee. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: A clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.M.; Adekolu, A.A.; Agrawal, R.; Zitun, M.; Maan, S.; Thakkar, S.; Singh, S. Endoscopic closure of esophageal, gastric, jejunal, and rectopelvic fistulas with cardiac septal occluder devices: A case series. VideoGIE 2024, 10, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J.; Miller, S.D.; Hoskins, B.J. Endoscopic removal of high-powered magnets from the appendiceal orifice in an asymptomatic child. JPGN Rep. 2025, 6, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Lv, Y. Gastrointestinal damage caused by swallowing multiple magnets. Front. Med. 2012, 6, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; Zhang, Q.M.; Lu, S.Y.; Liu, T.T.; Li, S.L.; Chen, L.; Xie, F.N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.H.; Wang, D.Y.; et al. Accidental ingestion of multiple magnetic beads by children and their impact on the gastrointestinal tract: A single-center study. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goparaju, N.; Yarbrough, D.P.; Fuller, G. Magnetic Mishap: Multidisciplinary Care for Magnet Ingestion in a 2-Year-Old. Emerg. Care Med. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodagum, L.; Truche, P.; Burjonrappa, S. “Signet Ring Sign” on Plain X-ray Indicates the Need for Surgical Intervention After Magnet Ingestion in Children. Cureus 2024, 16, e65943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, D.D.; Hiremath, A.; Jaber, G.; Al Marzouqi, M.M.; Mohammed, D. Enteroenteric Fistula: A Rare Sequela of Unwitnessed Magnet Ingestion in a Child. Cureus 2025, 17, e81950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Javaherizadeh, H. L-Shaped Configuration of Multiple Magnet Ingestion: A Case Report. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 2025, 17, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaswad, M.R.; Ghorab, W. Multiple magnet ingestion causing entero-enteric fistula, and intestinal obstruction: A case report. J. Med. Sci. Res. 2024, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Park, J. Surgical removal of ingested magnets in children: A retrospective clinical analysis of 16 patients and review of the literature. Medicine 2025, 104, e42903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Borić, M.; Markić, J.; Jukić, M.; Grandić, L. A Case of 2-Year-Old Child with Entero-Enteric Fistula Following Ingestion of 25 Magnets. Acta Med. 2016, 59, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Brown, R.; Millar, A.; Numanoglu, A.; Alexander, A.; Theron, A. The risks of gastrointestinal injury due to ingested magnetic beads. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phen, C.; Wilsey, A.; Swan, E.; Falconer, V.; Summers, L.; Wilsey, M. Non-Surgical Management of Gastroduodenal Fistula Caused by Ingested Neodymium Magnets. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2018, 21, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.I.; Oliva-Hemker, M.; Choi, J.; Lustik, M.; Gilger, M.A.; Noel, R.A.; Schwarz, K.; Nylund, C.M. Magnet ingestions in children presenting to US emergency departments, 2002-2011. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altokhais, T. Magnet Ingestion in Children Management Guidelines and Prevention. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 727988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusakhare, N.; Jain, A.; Sharma, N.; Singh, V.; Goyal, S.; Marhual, J.C.; Kathale, S. Multidisciplinary management of gastrocolic fistula post magnet ingestion: A case report and literature review highlighting early surgical recommendation. Int. Surg. J. 2022, 9, 1890–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Gomaa, S.; Alabdul Razzak, I.; Basrak, M.T. Endoscopic Removal of a Magnet Retained in the Stomach for Two Years: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e80562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, L.A.; Vasile, L.; Mogoş, G.F.R.; Şurlin, V.; Vîlcea, I.D.; Cercelaru, L.; Mogoantă, S.Ş.; Mărgăritescu, N.D.; Ţenea-Cojan, T.Ş. Appendiceal malakoplakia: A review of the literature and case presentation. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2025, 66, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Cercelaru, L.; Caragea, D.-C.; Vîlcea, I.-D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-Ș.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Vasile, L.; Țenea Cojan, T.Ș. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Cercelaru, L.; Vîlcea, I.-D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-S.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Țenea Cojan, T.S.; Vasile, L. Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambakis, G.; Schildkraut, T.; Delaney, I.; Gilmore, R.; Loebenstein, M.; Taylor, A.; Holt, B.; Tsoi, E.H.; Cameron, G.; Demediuk, B.; et al. Management of foreign body ingestion in adults: Time to STOP and rethink endoscopy. Endosc. Int. Open 2023, 11, E1161–E1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.C.; Wojda, T.R.; Jones, C.D.; Otey, A.J.; Stawicki, S.P. Intentional ingestions of foreign objects among prisoners: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 7, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negoita, L.M.; Ghenea, C.S.; Constantinescu, G.; Sandru, V.; Stan-Ilie, M.; Plotogea, O.-M.; Shamim, U.; Dumbrava, B.F.; Mihaila, M. Esophageal Food Impaction and Foreign Object Ingestion in Gastrointestinal Tract: A Review of Clinical and Endoscopic Management. Gastroenterol. Insights 2023, 14, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, J.R.; Relland, L.M.; Hagele, M.S.; Tobias, J.D. Ingested Magnets Found Inadvertently During Elective Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Med. Cases 2024, 15, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchi, J.A.; Shawis, R.N. Multiple magnet ingestion and gastrointestinal morbidity. Arch. Dis. Child. 2002, 87, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, K.M.; Padhani, A.R.; Revell, P.B.; Husband, J.E. Beware the stronger magnet. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1999, 173, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, N.L.; Denny, S.A.; Smith, G.A. Rare-Earth Magnet Ingestion-Related Injuries in the Pediatric Population: A Review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2015, 11, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Chan, L.C.N.; Hon, K.L.E.; Tsui, S.Y.B.; Pang, K.K.Y.; Cheung, H.M.; Leung, A.K.C. Magnetic Foreign Body Ingestion in Children: The Attractive Hazards. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2019, 2019, 3549242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaazan, P.; Seow, W.; Tan, Z.; Logan, H.; Philpott, H.; Huynh, D.; Warren, N.; McIvor, C.; Holtmann, G.; Clark, S.R.; et al. Deliberate foreign body ingestion in patients with underlying mental illness: A retrospective multicentre study. Australas. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birk, M.; Bauerfeind, P.; Deprez, P.H.; Häfner, M.; Hartmann, D.; Hassan, C.; Hucl, T.; Lesur, G.; Aabakken, L.; Meining, A. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Ikenberry, S.O.; Jue, T.L.; Anderson, M.A.; Appalaneni, V.; Banerjee, S.; Ben-Menachem, T.; Decker, G.A.; Fanelli, R.D.; Fisher, L.R.; et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 73, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Result (SI Units) | Reference Range (SI Units) |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | 15.0 ×109/L | 4.0–10.0 × 109/L |

| Sodium (Na+) | 132 mmol/L | 135–145 mmol/L |

| Potassium (K+) | 3.0 mmol/L | 3.5–5.0 mmol/L |

| Chloride (Cl−) | 90 mmol/L | 98–106 mmol/L |

| CRP | 120 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| Albumin | 28 g/L | 35–50 g/L |

| Day/Time | Event |

|---|---|

| Day 0 | Ingestion of 13 neodymium magnets (9 spheres, 4 disks) |

| Day 5 | Admission to emergency department with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting; ASA III, hemodynamically stable (BP 135/85 mmHg, HR 98 bpm, Temp 37.8 °C, SatO2 97%); mild dehydration noted |

| Day 5 | Abdominal X-ray: clustered radiopaque bodies in distal ileum; no free air |

| Day 5 | Preoperative management: IV fluid resuscitation, electrolyte correction, nasogastric decompression, prophylactic antibiotics (ceftriaxone + metronidazole), LMWH prophylaxis initiated |

| Day 5 | Emergency laparotomy: entero-enteric fistula (10 mm), resection of 18 cm ileum, side-to-side anastomosis, retrieval of 13 magnets |

| Postop 24 h | CRP 120 → 75 mg/L; WBC 15.0 → 11.0 × 109/L; continued IV antibiotics + LMWH |

| Postop 48 h | Oral clear liquids initiated; CRP 75 → 50 mg/L; WBC 11.0 → 9.5 × 109/L |

| Postop 72 h | Transition to soft diet; CRP 50 → 25 mg/L; WBC 9.5 → 8.5 × 109/L |

| Postop Day 5 | Bowel transit restored |

| Postop Day 7 | Discharged in good condition; antibiotics completed; LMWH stopped |

| Aspect | Pediatric Algorithm (NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN, Multicenter Data) | Adult Adaptation (Case Series, Reports) |

|---|---|---|

| Case frequency | Common; majority of magnet ingestion cases [6] | Rare; often intentional or psychiatric-related |

| Primary goal | Prevent perforations/fistulas; minimize surgery | Prevent complications; address psychiatric context |

| Initial workup | AP + lateral abdominal X-ray; US/CT if complications suspected [6] | AP + lateral X-ray; CT often used early for localization and complication assessment [29] |

| Single magnet approach | Observe ≤ 24 h; confirm progression [6] | Same as pediatric |

| Multiple magnet approach | Urgent endoscopy if accessible; otherwise prompt surgery [6] | Same principle, but lower surgical threshold if ingestion uncertain or patient noncompliant [29] |

| Role of endoscopy | Primary for magnets in stomach/duodenum | Primary if accessible; distal symptomatic cases often go directly to surgery |

| Monitoring | Inpatient, NPO, X-ray every 8–12 h | Same, plus routine psychiatric consult |

| Particularities | Standardized international algorithms | No dedicated adult guidelines; individualized adaptation |

| Author | Year | No. of Magnets | Adult/Child | Age | Fistula Location | Fistula (Yes/No/Not Reported) | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Özcan, R. [6] | 2024 | Multiple | Child | 6 years | Jejuno-colonic + volvulus | Yes | Surgical (fistula repair + devolvulation) |

| Blevrakis, E. [3] | 2018 | 2 | Child | 9 years | Jejuno-jejunal (two loops) | Yes | Surgical (laparotomy) |

| Doklestić, K. [4] | 2017 | 2 | Adult | 21 years | Jejuno-ileal | Yes | Surgical (primary suture of perforations) |

| Arshad, M. [11] | 2019 | Multiple | Child | 2 years | NA | No | Surgical |

| Zachos, K. [12] | 2019 | Multiple | Child | 4 years | Jejuno-ileal (double) | Yes | Surgical |

| Phen, C. [27] | 2018 | 13 | Child | 19 months | Gastroduodenal | Yes | Endoscopic + supportive |

| Pogorelić, Z. [25] | 2016 | 25 | Child | 2 years | Entero-enteric | Yes | Surgical (resection + anastomosis) |

| Freeman, J. [16] | 2025 | 2 | Child | 10 years | NA | No | Endoscopic (colonoscopy, extraction) |

| Goparaju, N. [21] | 2025 | 44 | Child | 2 years | NA | No | Multidisciplinary (ENT + endoscopic; remainder passed spontaneously) |

| Sodagum, L. [20] | 2024 | Multiple | Child | 17 months | Small bowel loops (“seal ring” sign) | Yes | Surgical |

| Balaswad, M. [23] | 2024 | Multiple | Child | 5 years | Entero-enteric + obstruction | Yes | Surgical (fistula excision + anastomoses) |

| Ahmed, H. [31] | 2025 | 1 | Adult | 45 years | NA | No | Endoscopic (Roth net) |

| Hakimzadeh, M. [22] | 2025 | Multiple | Child | 2 years | NA | No | Endoscopic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbu, L.A.; Cercelaru, L.; Vîlcea, I.-D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-S.; Țenea Cojan, T.S.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Țenea Cojan, A.-M.; Căluianu, V.; Popescu, M.; et al. Enteroenteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in an Adult: Case Report, Literature Review and Management Algorithm. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192523

Barbu LA, Cercelaru L, Vîlcea I-D, Șurlin V, Mogoantă S-S, Țenea Cojan TS, Mărgăritescu N-D, Țenea Cojan A-M, Căluianu V, Popescu M, et al. Enteroenteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in an Adult: Case Report, Literature Review and Management Algorithm. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192523

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbu, Laurențiu Augustus, Liliana Cercelaru, Ionică-Daniel Vîlcea, Valeriu Șurlin, Stelian-Stefaniță Mogoantă, Tiberiu Stefăniță Țenea Cojan, Nicolae-Dragoș Mărgăritescu, Ana-Maria Țenea Cojan, Valentina Căluianu, Mihai Popescu, and et al. 2025. "Enteroenteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in an Adult: Case Report, Literature Review and Management Algorithm" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192523

APA StyleBarbu, L. A., Cercelaru, L., Vîlcea, I.-D., Șurlin, V., Mogoantă, S.-S., Țenea Cojan, T. S., Mărgăritescu, N.-D., Țenea Cojan, A.-M., Căluianu, V., Popescu, M., Mogoș, G. F. R., & Vasile, L. (2025). Enteroenteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in an Adult: Case Report, Literature Review and Management Algorithm. Healthcare, 13(19), 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192523