Nurses’ Role in Patient Education for Managing Inflammatory Joint Diseases: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Bulgarian Rheumatology Clinics

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Role of Nurses in the Holistic Care of Patients with IJDs

2. Materials and Methods

- Formulating the main constructs of the survey

- Creating items for each construct and determining their type (yes/no, multiple choice).

- Editing the items and adding explanatory text where necessary.

- Pilot testing the first draft with 10 patients, whose responses were not included in the data pool.

- Making further edits and clarifications based on the insights gained through the pilot test.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

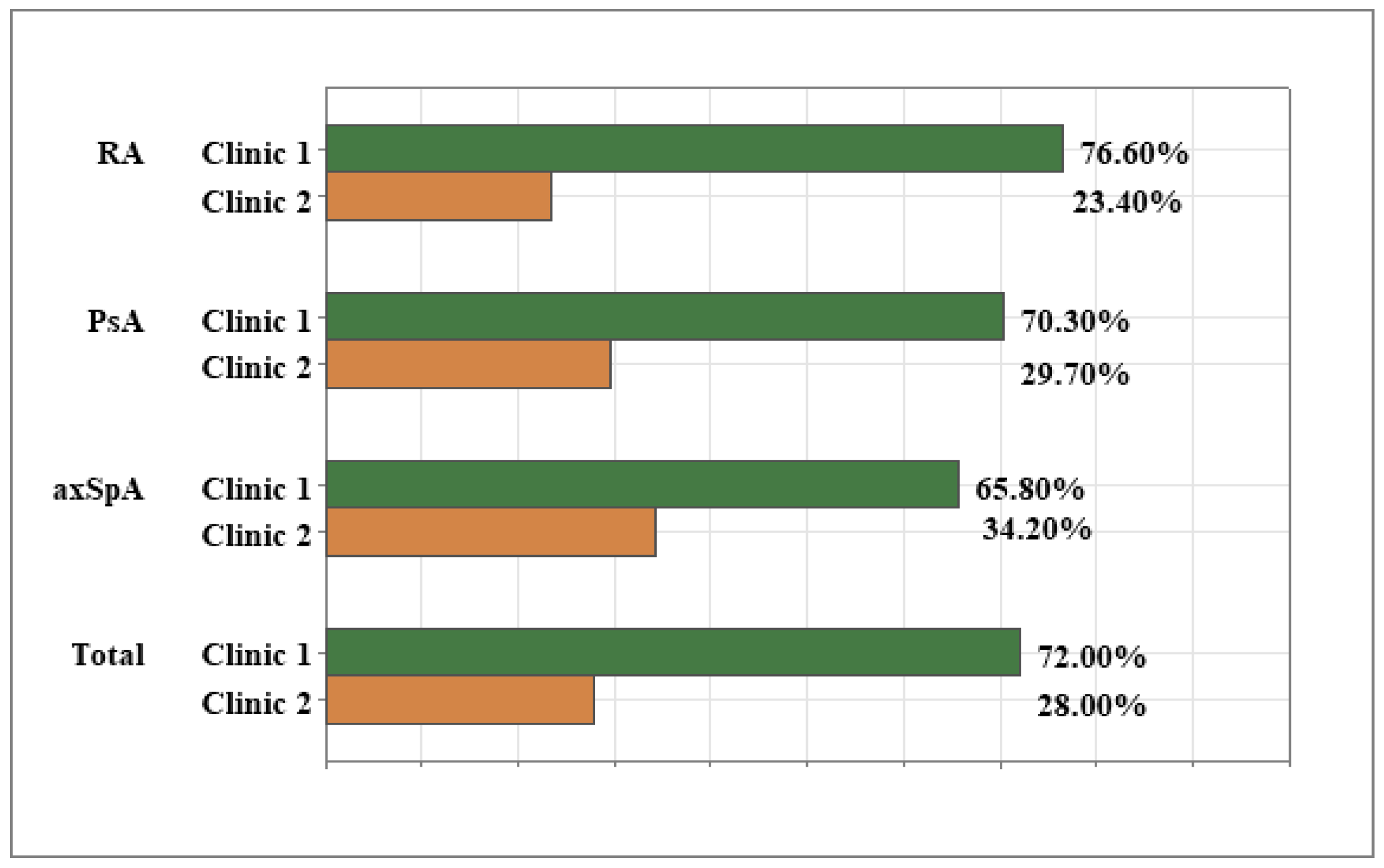

Ruling out Differences Related to Clinic of Treatment

3. Results

3.1. Background Information About the Patients

3.2. Nursing Support in Enhancing Patients’ Informedness About Inflammatory Joint Disease and Treatment

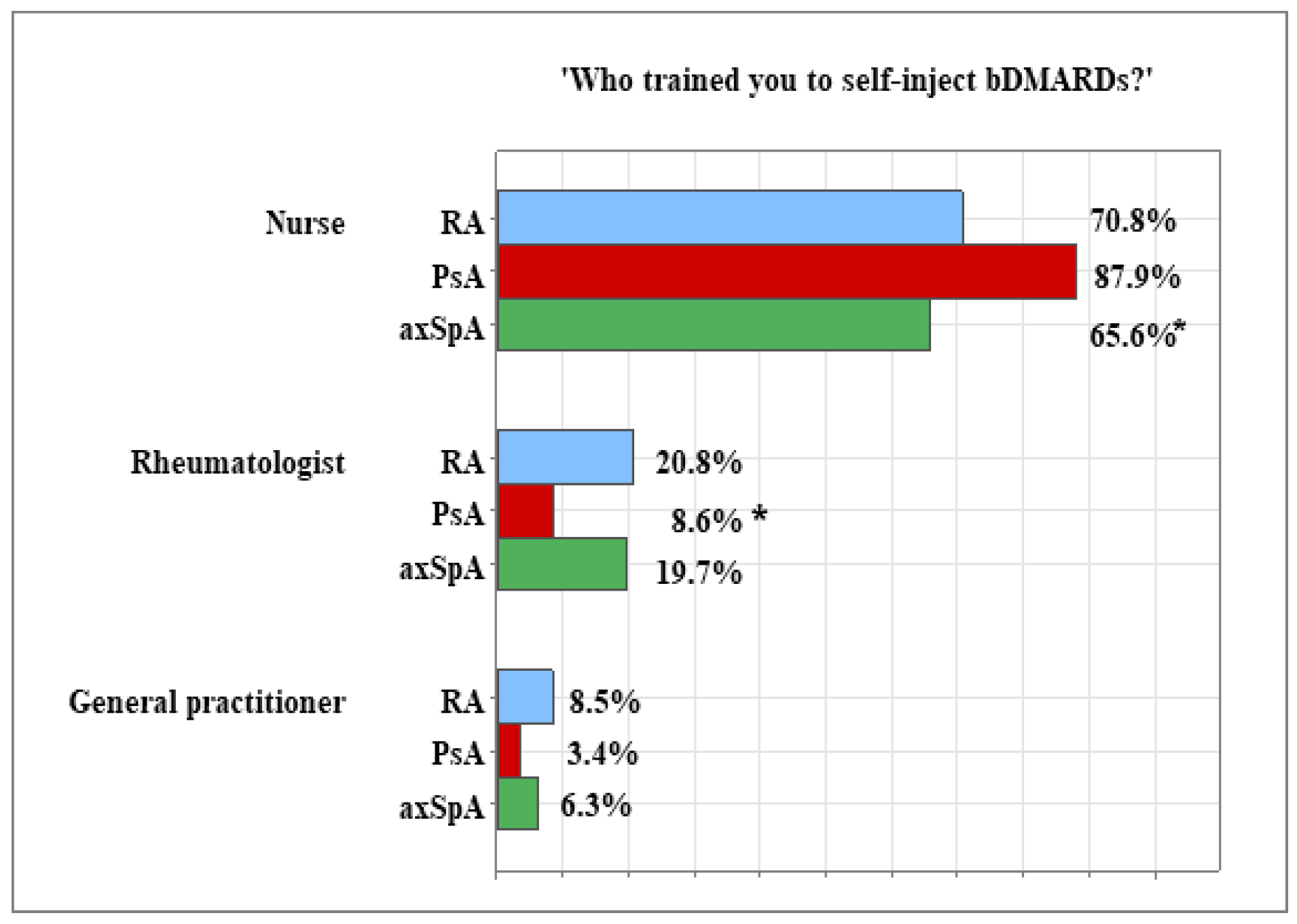

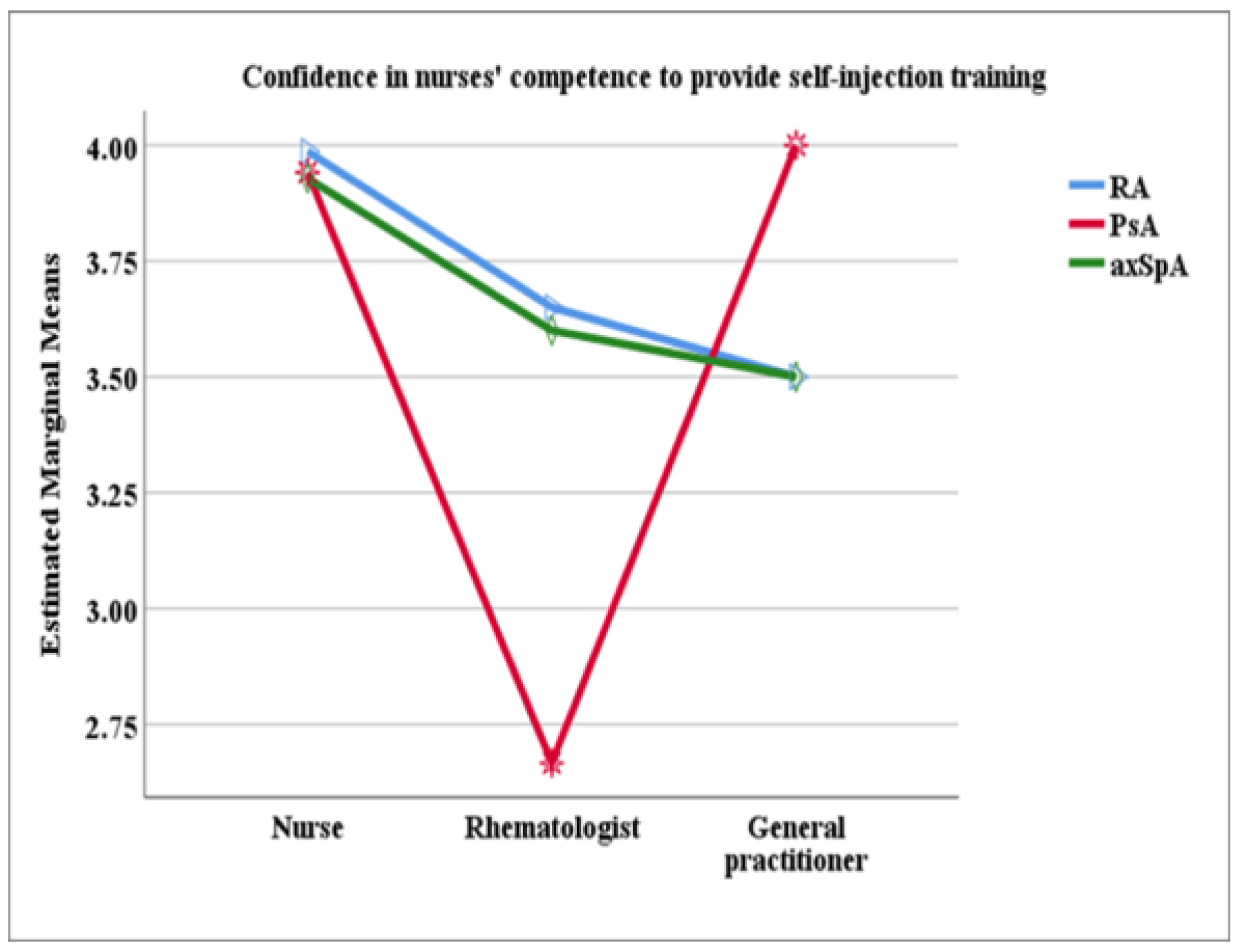

3.3. Nurses’ Role in Training Patients to Self-Inject bDMARDs

3.4. Nurses’ Role in Educating Patients with IJD to Adopt Healthy Living Habits and Maintain Psychological Well-Being

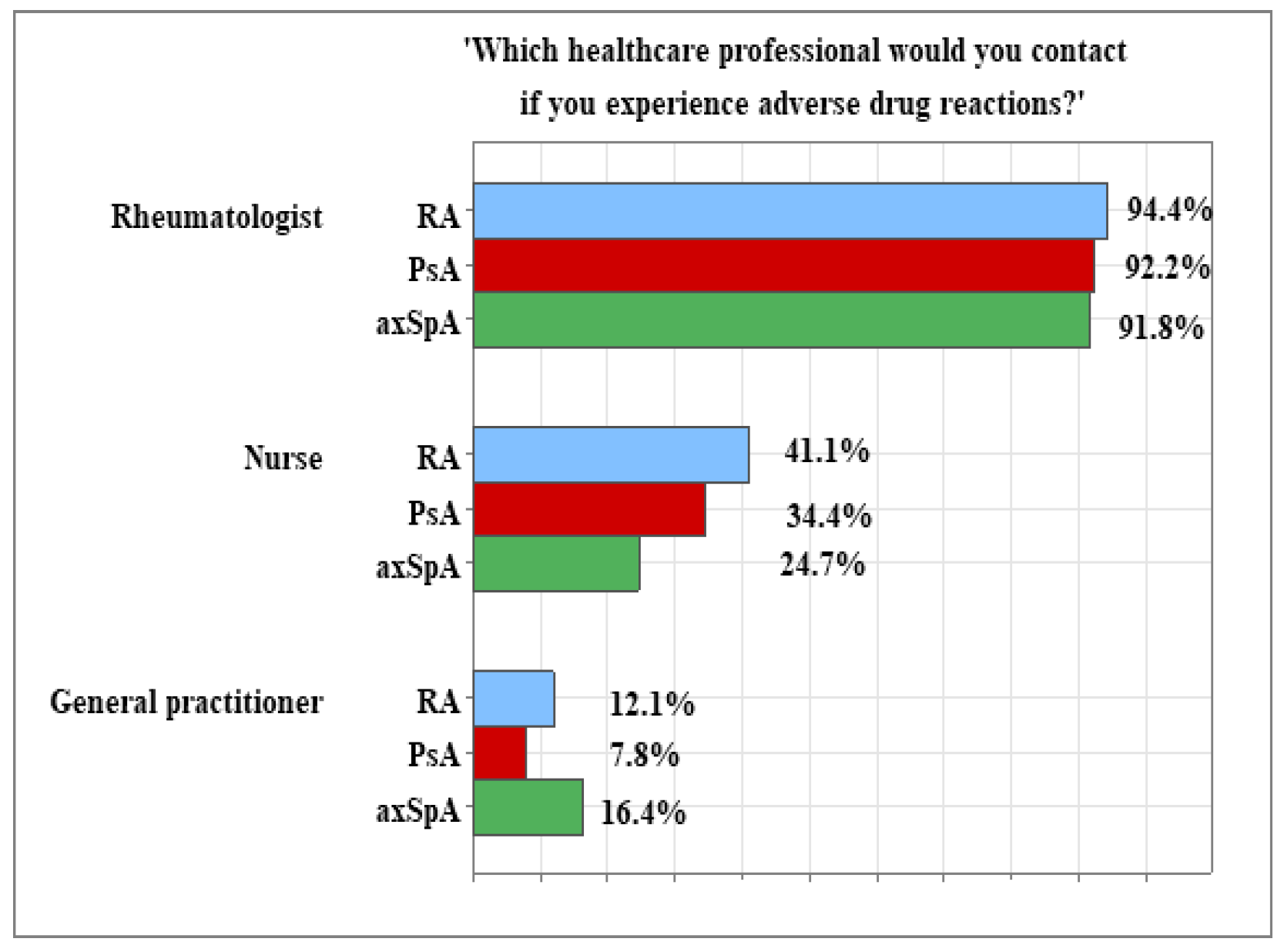

3.5. Patients’ Preparedness in the Event of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs)

3.6. Nursing Role in Enhancing the Overall Quality of Care for Patients with IJD

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IJD | Inflammatory Joint Disease |

| bDMARDs | biological Disease Modifying Anti Rheumatic Drugs |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| PsA | Psoriatic Arthritis |

| AxSpA | Axial Spondyloarthritis |

| ADRs | Adverse Drug Reactions |

| PROs | Patient Reported Outcomes |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary Team |

References

- Webers, C.; Essers, I.; Been, M.; Van Tubergen, A. Barriers and facilitators to application of treat-to-target management in psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis in practice: A systematic literature review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2024, 69, 152546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiphorou, E.; Santos, E.J.F.; Marques, A.; Böhm, P.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Daien, C.I.; Esbensen, B.A.; Ferreira, R.J.O.; Fragoulis, G.E.; Holmes, P. 2021 EULAR recommendations for the implementation of self-management strategies in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzban, S.; Najafi, M.; Agolli, A.; Ashrafi, E. Impact of Patient Engagement on Healthcare Quality: A Scoping Review. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.E.; A Zangi, H.; Larsson, I.; Beauvais, C.; Boström, C.; Domján, A.; van Eijk-Hustings, Y.; Van der Elst, K.; Fayet, F.; O Ferreira, R.J.; et al. Assessing acceptability and identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation of the EULAR recommendations for patient education in inflammatory arthritis: A mixed-methods study with rheumatology professionals in 23 European and Asian countries. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Han, K.; Cho, H.; Ju, J. Nursing teamwork is essential in promoting patient-centered care: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, K.; Frerichs, W.; Cöllen, K.; Lindig, A.; Härter, M.; Scholl, I. Perspective on patient-centered communication: A focus group study investigating the experiences and needs of nursing professionals. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on the Future of Nursing 2020–2030, National Academy of Medicine, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 25982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk-Hustings, Y.; van Tubergen, A.; Boström, C.; Braychenko, E.; Buss, B.; Felix, J.; Firth, J.; Hammond, A.; Harston, B.; Hernandez, C.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeisen, K.E.; Sewell, J.; Ostor, A.J.K. Biological Therapies for Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview for the Clinician. Biologics 2021, 15, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, B.; Primdahl, J.; van Tubergen, A.; Voshaar, M.; Zangi, H.A.; Barbosa, L.; Boström, C.; Boteva, B.; Carubbi, F.; Fayet, F.; et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, P.; Heaton, H.; Medcalf, P.; Campbell, J.; Whiteside, D. A nurse-led rheumatology telephone advice line: Service redesign to improve efficiency and patient experience. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthman, I.; Almoallim, H.; Buckley, C.D.; Masri, B.; Dahou-Makhloufi, C.; El Dershaby, Y.; Sunna, N.; Raza, K.; Kumar, K.; Huijer, H.A.-S.; et al. Nurse-led care for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: A review of the global literature and proposed strategies for implementation in Africa and the Middle East. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangi, H.A.; Ndosi, M.; Adams, J.; Andersen, L.; Bode, C.; Boström, C.; van Eijk-Hustings, Y.; Gossec, L.; Korandová, J.; Mendes, G. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPhilpot, L.M.; Khokhar, B.A.; DeZutter, M.A.; Loftus, C.G.; Stehr, H.I.; Ramar, P.; Madson, L.P.; Ebbert, J.O. Creation of a Patient-Centered Journey Map to Improve the Patient Experience: A Mixed Methods Approach. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, H.; Grønning, K. Are We Transitioning Toward Person-centered Practice on Self-management Support? An Explorative Case Study Among Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic Nurses in Norway. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021, 7, 23779608211037494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, M.R.; El Aoufy, K.; Bambi, S.; Bruni, C.; Guiducci, S.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Rasero, L. Nursing interventions for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases on biological therapies: A systematic literature review. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 42, 1521–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Thurah, A.; Esbensen, B.A.; Roelsgaard, I.K.; Frandsen, T.F.; Primdahl, J. Efficacy of embedded nurse-led versus conventional physician-led follow-up in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. RMD Open 2017, 3, e000481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougados, M.; Soubrier, M.; Perrodeau, E.; Gossec, L.; Fayet, F.; Gilson, M.; Cerato, M.-H.; Pouplin, S.; Flipo, R.-M.; Chabrefy, L.; et al. Impact of a nurse-led programme on comorbidity management and impact of a patient self-assessment of disease activity on the management of rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (COMEDRA). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, L.; Xiaodong, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Li, P. Competencies of nurses to participate in safe medication management practices for biologics: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelas, G.; Villaverde, V.; García, S.; Guerra, M.; León, M.J.; Cañete, J.D. Benefit of health education by a training nurse in patients with axial and/or peripheral psoriatic arthritis: A systematic literature review. Rheumatol. Int. 2016, 36, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraoui, B.; Jamal, S.; Ahluwalia, V.; Fung, D.; Manchanda, T.; Khraishi, M. Real-World Tocilizumab Use in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Canada: 12-Month Results from an Observational, Noninterventional Study. Rheumatol. Ther. 2018, 5, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Platania-Phung, C.; Watkins, A.; Scholz, B.; Curtis, J.; Goss, J.; Niyonsenga, T.; Stanton, R. Developing an Evidence-Based Specialist Nursing Role to Improve the Physical Health Care of People with Mental Illness. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyezkhankyzy, D.; Khojakulova, U.; Yessirkepov, M.; Qumar, A.B.; Zimba, O.; Kocyigit, B.F.; Akaltun, M.S. Nurses’ roles, interventions, and implications for management of rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afenigus, A.D.; Sinshaw, M.A. Developing nursing approaches across the chronic illness trajectory: A grounded theory study of care from diagnosis to end-of-life in Western Amhara, Ethiopia. Front. Health Serv. 2025, 5, 1502763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjö, A.; Bergsten, U. Patients’ experiences of frequent encounters with a rheumatology nurse—A tight control study including patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskelet. Care 2018, 16, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambushe, S.A.; Awoke, N.; Demissie, B.W.; Tekalign, T. Holistic nursing care practice and associated factors among nurses in public hospitals of Wolaita zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerola, A.; Rollefstad, S.; Kazemi, A.; Wibetoe, G.; Sexton, J.; Mars, N.; Kauppi, M.; Kvien, T.; Haavardsholm, E.; Semb, A. Psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in Norway: Nationwide prevalence and use of biologic agents. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 52, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamal, D.M.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Amin, A.A.; Khalil, S.A.; Samaan, S.F. Gender differences in axial spondyloarthritis regarding clinical, radiological characteristics and response to treatment in an Egyptian Cohort Study. Egypt Rheumatol. Rehabil. 2025, 52, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menis, J.; Doussiere, M.; Touboul, E.; Barbier, V.; Sobhy-Danial, J.-M.; Fardellone, P.; Mathurin Fumery, M.; Chaby, G.; Goëb, V. Current characteristics of a population of psoriatic arthritis and gender disparities. JCTR 2023, 9, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez Vodnizza, S.; Van Der Horst-Bruinsma, I. Sex differences in disease activity and efficacy of treatment in spondyloarthritis: Is body composition the cause? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2020, 32, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, M.L.; Ferreira, R.J.O.; Machado, P.M.; Marques, A.; Da Silva, J.A.P.; Ndosi, M. Educational needs in people with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damgaard, A.J.; Primdahl, J.; Esbensen, B.A.; Latocha, K.M.; Bremander, A. Self-management support needs of patients with inflammatory arthritis and the content of self-management interventions: A scoping review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2023, 60, 152203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.M.T.; Esbensen, B.A.; Blum, N.S.; Rønne, P.F.; Bremander, A.; Hendricks, O.; Østergaard, M.; Andersen, L.; Primdahl, J. Health professionals’ experiences delivering an Interdisciplinary Nurse-coordinated SELf-MAnagement intervention for patients with inflammatory arthritis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, N.S.; Esbensen, B.A.; Østergaard, M.; Bremander, A.; Hendricks, O.; Lindgren, L.H.; Andersen, L.; Jensen, K.V.; Primdahl, J. Patients’ experience of a novel interdisciplinary nurse-led self-management intervention (INSELMA)—A qualitative evaluation. BMC Rheumatol. 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.; Xin, T.; Yan, A.; Wu, L.; Wang, L. Effects of a Nurse-Led Educational Intervention for Chinese Adult Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: A Case-Control Study. OJN 2016, 06, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, L.C.; Orbai, A.M.; Azevedo, V.F.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Steinberg, K.; Lippe, R.; Lim, I.; Eder, L.; Richette, P.; Weng, M.Y.; et al. Results of a global, patient-based survey assessing the impact of psoriatic arthritis discussed in the context of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Hailey, L.H.; Suribhatla, R.; McGagh, D.; Amarnani, R.; Bundy, C.E.; Kirtley, S.; O’sUllivan, D.; Steinkoenig, I.; White, J.P.E.; et al. The impact of psoriatic arthritis on quality of life: A systematic review. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 16, 1759720X241295920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, C.; Fayet, F.; Rousseau, A.; Sordet, C.; Pouplin, S.; Maugars, Y.; Poilverd, R.M.; Savel, C.; Ségard, V.; Godon, B.; et al. Efficacy of a nurse-led patient education intervention in promoting safety skills of patients with inflammatory arthritis treated with biologics: A multicentre randomised clinical trial. RMD Open 2022, 8, e001828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessette, L.; Lebovic, G.; Millson, B.; Charland, K.; Donepudi, K.; Gaetano, T.; Remple, V.; Latour, M.G.; Gazel, S.; Laliberté, M.-C.; et al. Impact of the Adalimumab Patient Support Program on Clinical Outcomes in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Results from the COMPANION Study. Rheumatol. Ther. 2018, 5, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bemt, B.J.F.; Gettings, L.; Domańska, B.; Bruggraber, R.; Mountian, I.; Kristensen, L.E. A portfolio of biologic self-injection devices in rheumatology: How patient involvement in device design can improve treatment experience. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, F.; Olivieri, I.; Armuzzi, A.; Ayala, F.; Bettoli, V.; Bianchi, L.; Cimino, L.; Costanzo, A.; Cristaudo, A.; D’aNgelo, S.; et al. Multidisciplinary Management of Spondyloarthritis-Related Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disease. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primdahl, J.; Bremander, A.; Hendricks, O.; Østergaard, M.; Latocha, K.M.; Andersen, L.; Jensen, K.V.; Esbensen, B.A. Development of a complex Interdisciplinary Nurse-coordinated SELf-MAnagement (INSELMA) intervention for patients with inflammatory arthritis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschodt, M.; Heeren, P.; Cerulus, M.; Duerinckx, N.; Pape, E.; van Achterberg, T.; Vanclooster, A.; Dauvrin, M.; Detollenaere, J.; Heede, K.V.D.; et al. The effect of consultations performed by specialised nurses or advanced nurse practitioners on patient and organisational outcomes in patients with complex health conditions: An umbrella review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 158, 104840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatica, M.; Çela, E.; Ferraioli, M.; Costa, L.; Conigliaro, P.; Bergamini, A.; Caso, F.; Chimenti, M.S. The Effects of Smoking, Alcohol, and Dietary Habits on the Progression and Management of Spondyloarthritis. JPM 2024, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, O.; Kocyigit, B.F.; Kadam, E.; Haugeberg, G.; Grazio, S.; Guła, Z.; Strach, M.; Korkosz, M. Knowledge, perceptions, and practices of axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis and management among healthcare professionals: An online cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumthekar, A.; Bittar, M.; Dubreuil, M. Educational needs and challenges in axial spondyloarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2021, 33, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, V.; Field, R.; Ainsworth, P.; Edwards, C.J.; Cherry, L. Is There Evidence to Support Multidisciplinary Healthcare Working in Rheumatology? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Musculoskelet. Care 2015, 13, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kraan, Y.M.; Paap, D.; Lennips, N.; Veenstra, E.C.A.; Wink, F.R.; Kieskamp, S.C.; Spoorenberg, A. Patients’ Needs Concerning Patient Education in Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Qualitative Study. Rheumatol. Ther. 2023, 10, 1349–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Cumbrera, M.; Hillmann, O.; Mahapatra, R.; Trigos, D.; Zajc, P.; Weiss, L.; Bostynets, G.; Gossec, L.; Coates, L.C. Improving the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis and Axial Spondyloarthritis: Roundtable Discussions with Healthcare Professionals and Patients. Rheumatol. Ther. 2017, 4, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molto, A.; Gossec, L.; Poiraudeau, S.; Claudepierre, P.; Soubrier, M.; Fayet, F.; Wendling, D.; Gaudin, P.; Dernis, E.; Guis, S.; et al. Evaluation of the impact of a nurse-led program of patient self-assessment and self-management in axial spondyloarthritis: Results of a prospective, multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (COMEDSPA). Rheumatology 2021, 60, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, R.; Begg, S.; Spelten, E. What impact do chronic disease self-management support interventions have on health inequity gaps related to socioeconomic status: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, L.H.; de Thurah, A.; Thomsen, T.; Hetland, M.L.; Aadahl, M.; Vestergaard, S.B.; Kristensen, S.D.; Esbensen, B.A. Sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with negative illness perception in patients newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, or psoriatic arthritis—A survey based cross-sectional study. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelsen, B.; Fiane, R.; Diamantopoulos, A.P.; Soldal, D.M.; Hansen, I.J.W.; Sokka, T.; Kavanaugh, A.; Haugeberg, G. A Comparison of Disease Burden in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Axial Spondyloarthritis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabi, S.W.; Seleit, D.I.; Badran, A.; Koni, A.; Zyoud, S.H. Impact of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics on functional disability and health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study from Palestine. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteva, D.; Bakopoulou, K.; Padjen, I.; El Kaouri, I.; Tomov, L.; Vasilev, G.V.; Shumnalieva, R.; Velikova, T. Integrating Primary Care and Specialized Therapies in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Optimizing Recognition, Management, and Referral Practices. Rheumatol 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răuță, G.I.V.; Baltă, A.A.Ș.; Ciortea, D.-A.; Cliveți, C.L.P.; Grădinaru, M.Ș.; Matei, M.N.; Gurău, G.; Șuța, V.-C.; Voinescu, D.C. Healthcare Interventions in the Management of Rheumatic Diseases: A Narrative Analysis of Effectiveness and Emerging Strategies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesare, M.; D’Agostino, F.; Sebastiani, E.; Nursing and Public Health Group; Damiani, G.; Cocchieri, A. Deciphering the Link Between Diagnosis-Related Group Weight and Nursing Care Complexity in Hospitalized Children: An Observational Study. Children 2025, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Variables | RA n = 124 | PsA n = 64 | axSpA n = 73 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 63 (13.0) a | 58 (14.5) b | 49 (16.5) c | |

| 29–80 | 20–78 | 25–77 | <0.001 KW |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| 96 (77.4%) a | 33 (51.6%) b | 21 (28.8%) c | |

| 28 (22.6%) | 31 (48.4%) | 52 (71.2%) | <0.001 χ2 |

| Social status | ||||

| 48 (38.7%) a | 34 (53.1%) a, b | 48 (65.8%) b | |

| 44 (35.5%) | 17 (26.6%) | 8 (11.0%) | 0.001 χ2 |

| 32 (25.8%) | 13 (20.3%) | 17 (23.3%) | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||

| 13 (11.0) | 14 (7.0) | 14 (15.5) | |

| 4–49 | 4–32 | 4–47 | 0.442 KW |

| Visits to a rheumatology specialist | ||||

| (per-year counts) | ||||

| 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.0) | |

| 2–7 | 2–6 | 1–6 | 0.517 KW |

| bDMARDs treatment n (%) | ||||

| 106 (85.5%) | 58 (90.6%) | 64 (87.7%) | |

| 18 (14.5%) | 6 (9.4%) | 9 (12.3%) | 0.601 |

| Duration of bDMARDs therapy (years) | ||||

| 5.50 (4.0) | 7 (5.75) | 6 (5.0) | |

| 1–13 | 1–12 | 1–12 | 0.126 KW |

| In Your Experience, Do Nurses Contribute to Patient Care by Providing Information on the Following Issues? | RA n = 124 | PsA n = 64 | axSpA n = 73 | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| The disease and its management | 3.60 (0.85) | 3.68 (0.78) | 3.38 (0.97) | 2.33 | 0.099 |

| The treatment and its specifics | 3.60 (0.86) | 3.62 (0.87) | 3.31 (1.01) | 2.67 | 0.071 |

| The medical examinations and tests | 3.66 (0.83) | 3.63 (0.85) | 3.35 (0.96) | 2.91 | 0.056 |

| Statistics | RA n = 106 | PsA n = 58 | axSpA n = 64 | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMM | 3.90 | 3.81 | 3.85 | ||

| SE | 0.049 | 0.068 | 0.064 | 0.343 | 0.710 |

| In Your Experience, Do Nurses Contribute to Patient Care by: | RA | PsA | axSpA | F-Value df (2, 258) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Providing training aimed at healthy eating, alcohol and tobacco abuse, and improved health culture | 3.48 (0.88) | 3.52 (0.84) | 3.31 (1.00) | 1.93 | 0.147 |

| Educating patients about appropriate physical activity | 3.50 (0.88) | 3.52 (0.84) | 3.34 (1.00) | 1.46 | 0.233 |

| Offering psychological and emotional support | 3.72 (0.74) | 3.77 (0.69) | 3.54 (0.81) | 1.88 | 0.154 |

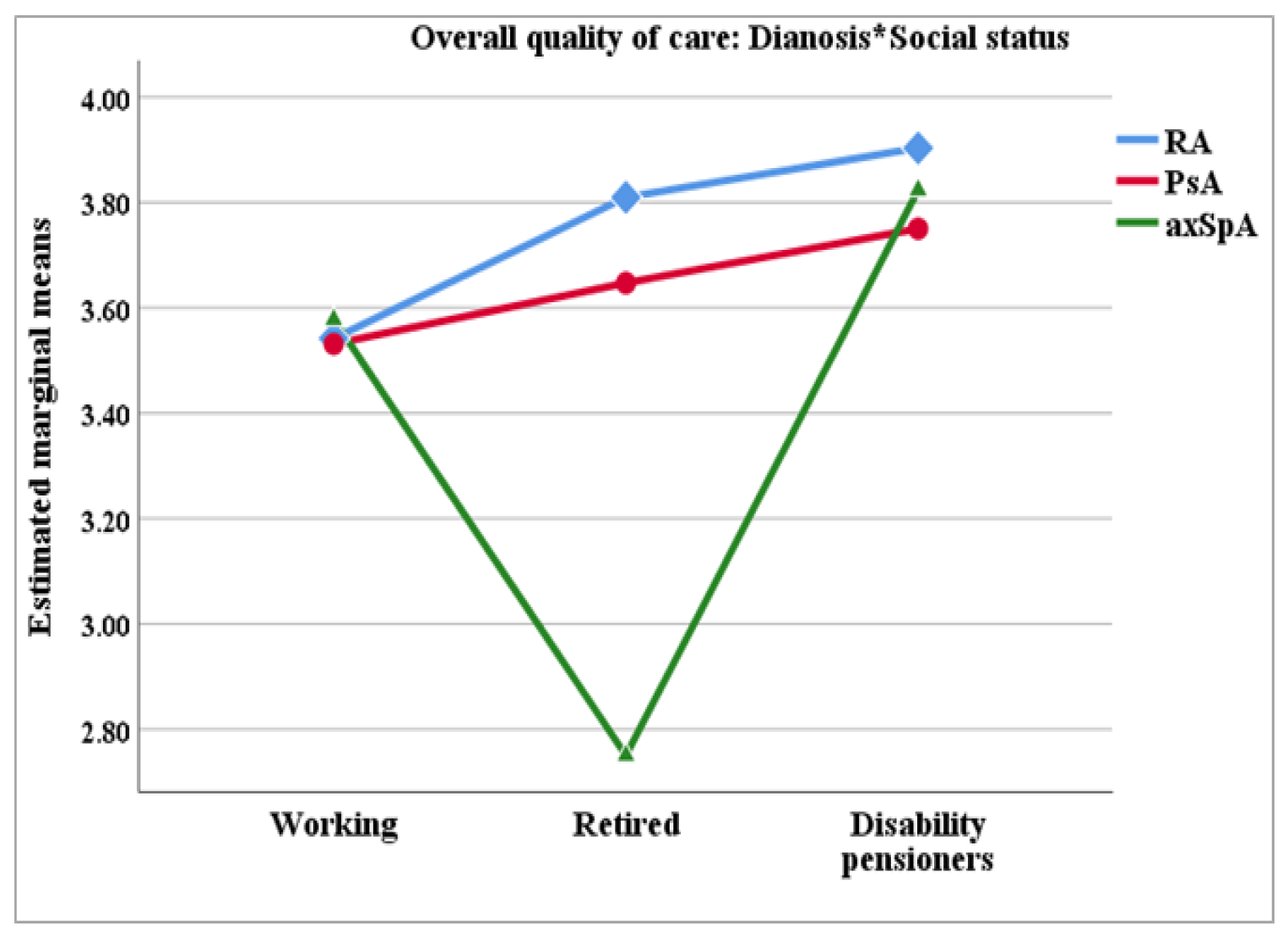

| Independent Variables | EMM (SE) | F-Value | ANCOVA p-Value | Partial Eta Squared | Bonferroni p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| RA | 3.78 (0.81) | RA ↔ PsA: 0.837 | ||||

| PsA | 3.63 (0.11) | 4.044 | 0.019 | 0.032 | RA ↔ axSpA: 0.015 | |

| axSpA | 3.34 (012) | PsA ↔ axSpA: 0.255 | ||||

| Social status | ||||||

| Working | 3.55 (0.08) | W ↔ R: 0.959 | ||||

| Retired | 3.38 (0.13) | 3.63 | 0.028 | 0.029 | W ↔ DP: 0.256 | |

| Disability pensioner | 3.81 (0.11) | R ↔ DP: 0.030 | ||||

| Diagnosis * Social status | ||||||

| RA | Working | 3.57 (0.12) | W ↔ R: 0.131 | |||

| Retired | 3.82 (0.14) | W ↔ DP: 0.028 | ||||

| Disability pensioners | 3.93 (0.15) | R ↔ DP: 0.295 | ||||

| PsA | Working | 3.53 (0.14) | W ↔ R: 0.749 | |||

| Retired | 3.61 (0.20) | 2.56 | 0.039 | 0.041 | W ↔ DP: 0.390 | |

| Disability pensioners | 3.74 (0.23) | R ↔ DP: 0.622 | ||||

| axSpA | Working | 3.56 (0.13) | W ↔ R: 0.031 | |||

| Retired | 2.70 (0.28) | W ↔ DP: 0.299 | ||||

| Disability pensioners | 3.76 (0.19) | R ↔ DP: 0.012 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoilova, S.; Popova-Belova, S.; Geneva-Popova, M. Nurses’ Role in Patient Education for Managing Inflammatory Joint Diseases: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Bulgarian Rheumatology Clinics. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192516

Stoilova S, Popova-Belova S, Geneva-Popova M. Nurses’ Role in Patient Education for Managing Inflammatory Joint Diseases: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Bulgarian Rheumatology Clinics. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192516

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoilova, Stefka, Stanislava Popova-Belova, and Mariela Geneva-Popova. 2025. "Nurses’ Role in Patient Education for Managing Inflammatory Joint Diseases: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Bulgarian Rheumatology Clinics" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192516

APA StyleStoilova, S., Popova-Belova, S., & Geneva-Popova, M. (2025). Nurses’ Role in Patient Education for Managing Inflammatory Joint Diseases: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Bulgarian Rheumatology Clinics. Healthcare, 13(19), 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192516