Mapping Community Priorities for Local Medical Centers: An Importance-Performance Analysis Study of Residents’ Perceptions in Large Cities, Non-Large Cities, and Rural Areas in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Importance–Performance Analysis Instrumentation and Measurement

2.2.2. Residential Area

2.2.3. Sociodemographic Variables

2.2.4. Health Status Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Health Status Profiles of Participants Across Residential Areas

3.2. Regional Patterns in the Perceived Importance and Performance of Local Medical Center Roles

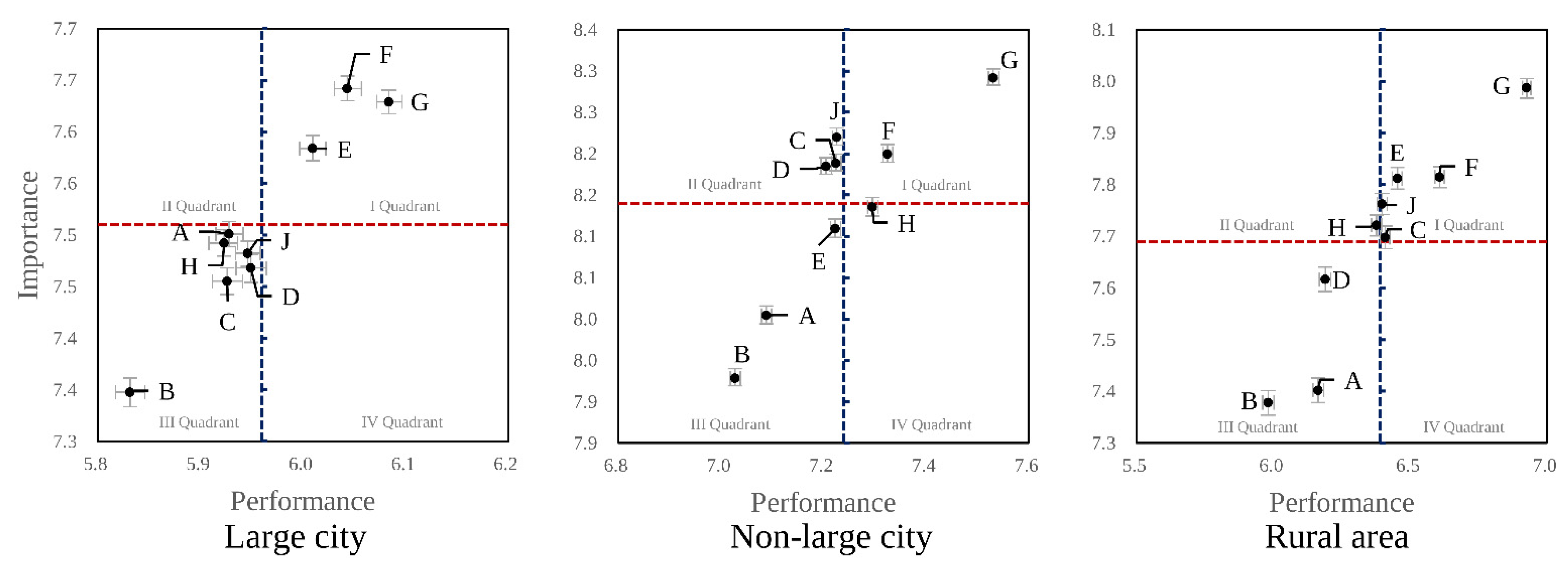

3.3. Final Priorities Determined by Importance Performance Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMC | Local Medical Center |

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CHNPI | Chungcheongnam-do Public Health Policy Institute |

| IPA | Importance-Performance Analysis |

References

- Weeks, W.B.; Chang, J.E.; Pagán, J.A.; Lumpkin, J.; Michael, D.; Salcido, S.; Kim, A.; Speyer, P.; Aerts, A.; Weinstein, J.N.; et al. Rural-urban disparities in health outcomes, clinical care, health behaviors, and social determinants of health and an action-oriented, dynamic tool for visualizing them. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care: Closing the Gap Between Public Health and Primary Care Through Integration; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/primary-health-care-closing-the-gap-between-public-health-and-primary-care-through-integration (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Cross, S.H.; Califf, R.M.; Warraich, H.J. Rural-Urban Disparity in Mortality in the US From 1999 to 2019. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 325, 2312–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, R. Rural health around the world: Challenges and solutions. Fam. Pract. 2003, 20, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, H.Y. Inter-regional patient outmigration to Seoul in South Korea. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 3, e11921725. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, D.S. Balancing accessibility and human resources in Korea: A nationwide distributional analysis. Ewha Med. J. 2023, 46, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. What Primary Health Networks Do. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/phn/what-PHNs-do (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare; Related Ministries. Comprehensive Measure for the Expansion of Public Health Care; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Comprehensive Measures for the Development of Public Health Care; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2018. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2023 White Paper on Health and Welfare; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2023; Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10107010202&bid=0037&act=view&list_no=1483888 (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean)

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The 2nd Public Healthcare Basic Plan (2021–2025); Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021; Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10401000000&bid=0008&act=view&list_no=367810 (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean)

- Bae, J.Y.; Oh, S.J.; Seo, J.H.; Ji, C.G.; Yoon, K.J.; Kwak, M.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.W. A Study on Improving the Payment and Financial Support System for Public Healthcare Institutions: Focusing on Local Public Hospitals; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.Y. Reimbursement Schemes and Financial Support to Local Public Hospitals. Health Welf. Forum 2022, 311, 36–49. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Korea. Enforcement Decree of the Local Autonomy Act, Article 118. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/jomunPrint.do?hseq=60856&cseq=2026167 (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean; Official English Translation Available).

- Du, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y. Urban and rural disparities in general hospital accessibility within a Chinese metropolis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Huh, D.W.; Kwon, Y.G. Local healthcare resources associated with unmet healthcare needs in South Korea: A spatial analysis. Geospat. Health 2025, 20, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. WHO Behavioural and Cultural Insights Flagship—Tailoring Health Policies; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/m/item/who-behavioural-and-cultural-insights-flagship---tailoring-health-policies (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Health Systems Governance—Overview. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-systems-governance (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kim, M.Y.; Lee, S.H. Recognition and role of public health care in public hospital staffs: Analysis of consensus conference by regions. Korean Public Health Res. 2019, 45, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.S.; Jeon, J.A.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Park, G.R.; Choi, J.H.; Son, J.I.; Kim, G.M. Current Status and Future Direction of Public Medical System: Focus on Regional Public Hospital and National University Hospital; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2014. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Organizing Committee for Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement in Health & Health Care Programs & Policies. Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement: A Conceptual Model to Advance Health Equity Through Transformed Systems for Health. NAM Perspect 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Las Nueces, D.; Hacker, K.; DiGirolamo, A.; Hicks, L.S. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 47, 1363–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riffin, C.; Kenien, C.; Ghesquiere, A.; Dorime, A.; Villanueva, C.; Gardner, D.; Callahan, J.; Capezuti, E.; Reid, M.C. Community-based participatory research: Understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2016, 5, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Republic of Korea. Act on the Establishment and Operation of Local Medical Centers. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=25144&lang=ENG (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean).

- Hagiya, H. Letter to the editor: A need for infectious disease specialists in public healthcare centers? J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Borces, K.G.; Bhattacharyya, D.S.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; Adams, A. Healthcare systems strengthening in smaller cities in Bangladesh: Geospatial insights from the municipality of Dinajpur. Health Serv. Insights 2020, 13, 1178632920951586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Jun, H.-J. Spatial disparities and contributing factors in medical facility accessibility: A comparative analysis across different-sized medical facilities. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2024, 59, 74–97. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Yun, I.; Moon, J.Y. Impact of Medical Resources in Residential Area on Unmet Healthcare Needs: Findings from a Multi-Level Analysis of Korean Nationwide Data. Heliyon 2025, 11, e40935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.T.; Sidani, S.; Butler, J.I.; Skinner, M.W.; Macdonald, M.; Durocher, E.; Hunter, K.F.; Wagg, A.; Weeks, L.E.; MacLeod, A.; et al. Optimizing hospital-to-home transitions for older persons in rural communities: A participatory, multimethod study protocol. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2021, 2, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowhaniuk, N. Exploring country-wide equitable government health care facility access in Uganda. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.E.; Etchin, A.G.; Guthrie, B.J.; Benneyan, J.C. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltman, R.B.; Durán, A.; Dubois, H.F.W. (Eds.) Governing Public Hospitals: Reform Strategies and the Movement Towards Institutional Autonomy; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gauld, R.; Asgari-Jirhandeh, N.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Reshaping public hospitals: An agenda for reform in Asia and the Pacific. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalilvand, M.A.; Raeisi, A.R.; Shaarbafchizadeh, N. Hospital governance accountability structure: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, W.; Reidhead, M.; Jansen, R.; Boyd, C.; Geng, E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Hospitals in the United States. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2023, 133, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.; Kim, P.-M.; Kim, C.-M.; Choi, C.-J.; Shin, H.-Y. The Act on Integrated Support for Community Care Including Medical and Nursing Services: Implications for the Role of Tertiary Hospitals in the Republic of Korea. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Republic of Korea. Act on Integrated Support for Community Care Including Medical and Nursing Services; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2024; Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=261447 (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean)

- Ravaghi, H.; Guisset, A.-L.; Elfeky, S.; Nasir, N.; Khani, S.; Ahmadnezhad, E.; Abdi, Z. A Scoping Review of Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment: Concepts, Rationale, Tools and Uses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Ling, E.J.; Bitton, A.; Cammett, M.; Cavanaugh, K.; Chopra, M.; El-Jardali, F.; Macauley, R.J.; Muraguri, M.K.K.; Konuma, S.; et al. Building resilient health systems: A proposal for a resilience index. Br. Med. J. 2017, 357, j2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, A.D.; Niessen, L.W.; Bhardwaj, M.; Alhassan, Y.; Khan, J.A.M. Factors Influencing the Efficiency of Public Hospitals in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Suggestions for Improvement. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 922597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function Label and Abbreviation | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Staff professional training | Offering professional development and training opportunities for medical staff |

| B | Medical knowledge innovation | Development of medical knowledge and innovation in disease treatment technologies |

| C | High-quality healthcare | Provision of high-quality healthcare for local residents |

| D | Unmet or essential healthcare services | Delivering unmet or essential healthcare services, including advanced emergencies, psychiatric, rehabilitation, maternal, and neonatal care, which are often avoided by private healthcare providers |

| E | Care for vulnerable populations | Ensuring access to medical care for vulnerable populations—such as the economically disadvantaged, women, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and those living in remote communities |

| F | Public health policy implementation | Implementation of public health policies and initiatives by the national government or the Chungcheongnam-do Provincial Government |

| G | Infectious disease control | Provision of a comprehensive range of services for the prevention, detection, management, and control of infectious diseases |

| H | Coordinated post-discharge care | Providing coordinated care for discharged patients by fostering close collaboration and referral networks among hospitals, clinics, and community welfare services |

| J | Operational efficiency | Proactive measures to advance operational efficiency and institutional competence |

| Variables | Categories | Total n (%) | Large City n (%) | Non-Large City n (%) | Rural Area n (%) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2057 (100) | 624 (30.3) | 991 (48.2) | 442 (21.5) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 1049 (51.0) | 318 (51.0) | 511 (51.6) | 220 (49.8) | 0.4 | 0.822 |

| Female | 1008 (49.0) | 306 (49.0) | 480 (48.4) | 222 (50.2) | |||

| Age (year) | 19~29 | 229 (14.5) | 118 (18.9) | 136 (13.7) | 45 (10.2) | 97.7 | <0.001 |

| 30~39 | 301 (14.6) | 119 (19.1) | 144 (14.5) | 38 (8.6) | |||

| 40~49 | 377 (18.3) | 129 (20.7) | 188 (19.0) | 60 (13.5) | |||

| 50~59 | 394 (19.1) | 120 (19.2) | 191 (19.3) | 83 (18.7) | |||

| ≥60 | 687 (33.4) | 138 (22.1) | 332 (33.5) | 217 (49.0) | |||

| Educational attainment | ≤Middle school | 545 (26.5) | 96 (15.4) | 261 (26.4) | 188 (42.5) | 105.7 | <0.001 |

| High school | 775 (37.7) | 292 (46.8) | 348 (35.2) | 135 (30.5) | |||

| ≥College | 736 (35.8) | 236 (37.8) | 381 (38.5) | 119 (26.9) | |||

| Type of health insurance | National Health Insurance | 2001 (97.3) | 606 (97.1) | 962 (97.2) | 433 (97.7) | 0.5 | 0.792 |

| Medical aid | 56 (2.7) | 18 (2.9) | 28 (2.8) | 10 (2.3) | |||

| Self-rated health status | Poor | 221 (10.7) | 33 (5.3) | 288 (29.1) | 70 (15.8) | 46.9 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 538 (26.1) | 142 (22.7) | 287 (29.8) | 108 (24.4) | |||

| Good | 1300 (63.1) | 450 (72.0) | 585 (59.0) | 265 (59.8) | |||

| Number of diagnosed chronic disease | 0 | 1224 (59.5) | 466 (74.7) | 551 (55.6) | 207 (46.8) | 102.7 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 419 (20.4) | 96 (15.4) | 216 (21.8) | 107 (24.2) | |||

| ≥2 | 414 (20.1) | 62 (9.9) | 224 (22.6) | 128 (29.0) |

| Rank | Importance | Performance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large City (n = 624) | Non-Large City (n = 990) | Rural Area (n = 443) | Large City (n = 624) | Non-Large City (n = 990) | Rural Area (n = 443) | |||||||

| Function | M ± SD | Function | M ± SD | Function | M ± SD | Function | M ± SD | Function | M ± SD | Function | M ± SD | |

| 1st | F | 7.64 ± 1.7 | G | 8.29 ± 1.5 | G | 7.99 ± 1.9 | G | 6.08 ± 1.4 | G | 7.53 ± 1.5 | G | 6.93 ± 1.6 |

| 2nd | G | 7.63 ± 1.6 | J | 8.22 ± 1.5 | F | 7.81 ± 2.1 | F | 6.04 ± 1.6 | F | 7.32 ± 1.5 | F | 6.61 ± 1.8 |

| 3rd | E | 7.58 ± 1.7 | F | 8.20 ± 1.5 | E | 7.81 ± 2.1 | E | 6.01 ± 1.6 | H | 7.30 ± 1.6 | E | 6.45 ± 1.9 |

| 4th | H | 7.50 ± 1.7 | C | 8.19 ± 1.5 | J | 7.76 ± 2.1 | D | 5.95 ± 1.7 | J | 7.23 ± 1.6 | C | 6.41 ± 1.8 |

| 5th | A | 7.49 ± 1.7 | D | 8.18 ± 1.6 | H | 7.72 ± 2.1 | J | 5.95 ± 1.6 | C | 7.22 ± 1.5 | J | 6.40 ± 1.8 |

| 6th | J | 7.48 ± 1.7 | H | 8.14 ± 1.6 | C | 7.70 ± 2.3 | H | 5.93 ± 1.6 | E | 7.22 ± 1.6 | H | 6.38 ± 1.8 |

| 7th | D | 7.47 ± 1.9 | E | 8.11 ± 1.6 | D | 7.62 ± 2.3 | C | 5.93 ± 1.7 | D | 7.20 ± 1.6 | D | 6.19 ± 2.1 |

| 8th | C | 7.46 ± 1.8 | A | 8.00 ± 1.6 | A | 7.40 ± 2.3 | A | 5.92 ± 1.6 | A | 7.09 ± 1.6 | A | 6.16 ± 2.0 |

| 9th | B | 7.35 ± 1.8 | B | 7.93 ± 1.7 | B | 7.38 ± 2.3 | B | 5.83 ± 1.8 | B | 7.03 ± 1.6 | B | 5.98 ± 2.0 |

| Total mean | 7.51 ± 1.6 | 8.14 ± 1.4 | 7.69 ± 2.1 | 5.96 ± 1.5 | 7.24 ± 1.4 | 6.39 ± 1.7 | ||||||

| Quadrant of IPA Matrix | Large City | Non-Large City | Rural Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Quadrant (Keep up the good work, Keep) | E, F, G | F, G | C, E, F, G, J |

| II Quadrant (Concentrate here, Improve) | - | C, D, J | H |

| III Quadrant (Low Priority) | A, B, C, D, H, J | A, B, E | A, B, D |

| IV Quadrant (Possible Overkill, Reduce) | - | H | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, H.; Seo, J.; Chung, E. Mapping Community Priorities for Local Medical Centers: An Importance-Performance Analysis Study of Residents’ Perceptions in Large Cities, Non-Large Cities, and Rural Areas in South Korea. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2513. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192513

Jeong H, Seo J, Chung E. Mapping Community Priorities for Local Medical Centers: An Importance-Performance Analysis Study of Residents’ Perceptions in Large Cities, Non-Large Cities, and Rural Areas in South Korea. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2513. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192513

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Hana, Jaehee Seo, and Eunyoung Chung. 2025. "Mapping Community Priorities for Local Medical Centers: An Importance-Performance Analysis Study of Residents’ Perceptions in Large Cities, Non-Large Cities, and Rural Areas in South Korea" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2513. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192513

APA StyleJeong, H., Seo, J., & Chung, E. (2025). Mapping Community Priorities for Local Medical Centers: An Importance-Performance Analysis Study of Residents’ Perceptions in Large Cities, Non-Large Cities, and Rural Areas in South Korea. Healthcare, 13(19), 2513. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192513